Fred Upton’s Bid at Protecting Automotive Security Negligence [Updated]

I’ve written about Ed Markey’s SPY Act, one of several efforts to respond to network insecurity in cars. Fred Upton, who represents Kalamazoo, MI, is pushing an alternative version as part of larger reform to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. It appears to be an attempt to forestall regulation from other directions. Update: Here’s a draft of the bill.

Take, for example, its call for a privacy policy. Whereas Markey’s bill requires manufacturers to provide a dashboard informing customers about their privacy policy (after all, all cars have an EPA report), Upton’s only requires it to be posted … somewhere.

More importantly, though, the bill establishes a $1 million cap on damages for manufacturers who refuse to have or violate their policy, and it pre-empts FTC action on unfair trade practices (of the sort that just got Wyndham Hotels in trouble).

This section provides that if a manufacturer does not file a privacy policy or violates any of the terms in its policy, the manufacturer is liable to the U.S. Government for a civil penalty of $5,000 per day, with a maximum penalty for a series of violations of $1,000,000. This section also provides that a manufacturer that submits a privacy policy identifying that it meets all seven of the privacy elements described in this section is not subject to civil penalties. It establishes a safe harbor from Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act with respect to any unfair or deceptive act or practice relating to privacy for any manufacturer whose privacy policy and practices meet all seven of the privacy elements described in this section.

Car companies are going to opt to pay that $1M instead of telling their customers how they’re using their driving data.

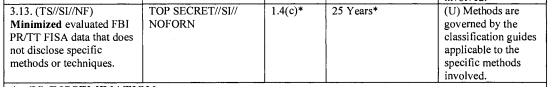

The cybersecurity requirement likewise serves more to protect companies than to impose sound security on them. Whereas Markey’s bill would require certain things from a cybersecurity policy, Upton’s would let the industry to establish a standard, than permit manufacturers to submit their plans that would fulfill “some or all” standards. Once they submitted those plans they would disappear — they couldn’t be FOIAed, and couldn’t be sued by FTC if they violated those terms.

This section exempts vehicle security and integrity plans submitted by manufacturers from Freedom of Information Act requests.

This section provides that a manufacturer that violates its vehicle security and integrity plan is subject to civil penalties. A manufacturer is not subject to those civil penalties (but doesn’t get the liability protections) if it submits a vehicle security and integrity plan that is approved by the Administrator and implements and maintains the best practices identified in their plan. This section provides that the best practices issued by the Council may not provide a basis for or evidence of liability against a manufacturer whose cybersecurity practices are alleged to be inconsistent with the best practices if the manufacturer has not filed a vehicle security and integrity plan and if the plan does not include the cybersecurity practice at issue.

This section also establishes a safe harbor from Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act with respect to the best practices identified and implemented and maintained in the vehicle security and integrity plan submitted by a manufacturer.

In other words, these plans don’t have to be sound if they can get NHTSA’s buy off on them (remember, NHTSA by it own admission doesn’t have software expertise, which was why Toyota got away with its acceleration problem for so long), and once they were in place if the company mostly fulfilled them they would be largely immune from regulation.

Which is why I believe this section does what I’m afraid it does: make it harder for independent researchers to review carmakers code.

This section establishes that it is unlawful for any person to access, without authorization, electronic control units or critical safety systems in a vehicle, or other systems containing driving data either wirelessly or through a wired connection. It establishes a civil penalty of $100,000 for a person who violates this section.

The actual language of the bill does not include a researcher’s exception.

(1) PROHIBITION.—It shall be unlawful for any person to access, without authorization, an electronic control unit or critical system of a motor vehicle, or other system containing driving data for such motor vehicle, either wirelessly or through a wired connection.

It also imposes a penalty for each thing hacked (so doing research would get really expensive quickly).

Update: NHTSA is no more impressed than I am.

The Committee’s discussion draft includes an important focus on cybersecurity, privacy and technology innovations, but the current proposals may have the opposite of their intended effect. By providing regulated entities majority representation on committees to establish appropriate practices and standards, then enshrining those practices as de facto regulations, the proposals could seriously undermine NHTSA’s efforts to ensure safety. Ultimately, the public expects NHTSA, not industry, to set safety standards.

Nor do the privacy people at FTC, which reads the privacy provisions to be even worse than I did.

Under this proposal, manufacturers can satisfy the requirements of this section without providing any substantive protections for consumer data. For example, a manufacturer’s policy could qualify for a safe harbor even if it states that the manufacturer collects numerous types of personal information, sells the information to third parties, and offers no choices to opt out of such collection or sale. Moreover, because the safe harbor exempts a manufacturer from FTC oversight, and Section 32402(d)(2) provides a separate exemption from civil penalties, a manufacturer that submits a privacy policy that meets the requirements of Section 32402(b) but does not follow it would not be subject to any enforcement mechanism.

Like me, it reads the hacking provision to prohibit research, thus leading to less cybersecurity.

By prohibiting such access even for research purposes, this provision would likely disincentivize such research, to the detriment of consumers’ privacy, security, and safety.

And it has the same concerns I do about providing immunity for crappy cybersecurity practices.

Finally, the proposed safe harbor is so broad that it would immunize manufacturers from liability even as to deceptive statements made by manufacturers relating to the best practices that they implement and maintain. For example, false claims on a manufacturer’s website about its use of firewalls, encryption, or other specific security features would not be actionable if these subjects were also covered by the best practices.

In sum, the Commission understands the desire to provide businesses with certainty and incentives, in the form of safe harbors, to implement best practices. However, the security provisions of the discussion draft would allow manufacturers to receive substantial liability protections in exchange for potentially weak best practices instituted by a Council that they control. The proposed legislation, as drafted, could substantially weaken the security and privacy protections that consumers have today.