MMT On Inflation

Posts in this series

The Deficit Myth By Stephanie Kelton: Introduction And Index

Debunking The Deficit Myth

The second chapter of Stephanie Kelton’s The Deficit Myth deals with inflation. In Chapter 1, Kelton explains that the deficit is not a constraint on government spending. Instead, inflation is the important constraint. A deficit does not prove that the federal government is overspending. Only an increase in inflation proves Congress is overspending. Kelton says Congress shouldn’t tax and spend so as to deliver a balanced budget. Congress should spend and tax so as to deliver a balanced economy, one that serves all of us. She says that historically we have not done this, that we have chosen to focus of deficits and in so doing our economy has not served us well.

Definition and Description of Inflation

Inflation means a continuous rise in the price level. A bit of inflation is considered harmless and even something economists like to see in a healthy, growing economy. But if prices start rising faster than most people’s incomes, it means a widespread loss of purchasing power. Left unchecked, this would mean a decline in society’s real standard of living. In extreme cases, prices can even spiral out of control, gripping a country in hyperinflation. P. 44.

The danger of eroding incomes explains why everybody worries about inflation, and explains why politicians can use the threat of inflation to terrorize voters. It works, even though the problem for more than a decade hasn’t been too much inflation, it’s been too little. Ever since the Great Crash inflation has been less than 2% annually despite efforts of the Fed.

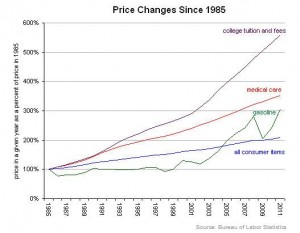

Kelton says that economists think of inflation as either cost-push or demand-pull. Demand-pull inflation occurs when consumer spending rises faster than the economy can produce goods and services. That hasn’t been a problem for a long time. Cost-push inflation can arise from disasters, which reduce the supply of something; from pricing power, as in the case of Big Pharma with its patents and trade secrets; or from workers gaining market power and demanding higher wages which businesses pass on to consumers. That last one is the only fear mainstream economists suffer, as far as I can tell.

The dominant theory of inflation stems from Milton Friedman’s monetarism:

According to Friedman, “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” What he meant was that too much money is the culprit in any inflationary episode. If prices weren’t stable, it was because the central bank was trying to force the economy to create too many jobs by allowing the money supply to increase too rapidly.

The early neoliberal Friedman insisted that the Fed must never interfere with the workings of the market. Specifically, the Fed should not try to reduce unemployment below a certain level, which came to be called NAIRU, the non-accelerating inflationary rate of unemployment. Friedman thought there had to be some minimum level of unemployment in the economy. [1] The Fed bought into this view, as did politicians of all stripes. They all agreed that to keep prices stable, the US has to accept a certain level of unwanted unemployment. And to be on the safe side, maybe a bit higher level of unemployment. In practice, Congress dumped the problems of inflation and unemployment on the Fed.

But problems arose. The NAIRU isn’t visible or measurable. It can only be seen in retrospect. And now we are pretty sure there isn’t a clear relationship between inflation and unemployment, as the Fed assumed. [2] The Fed Chair, Jerome Powell, freely admitted to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez that the Fed has been wrong about NAIRU, but defended its use on the grounds that “We need to have some sense of whether unemployment is high, low or just right.” P. 53.

2. The Problem of Unemployment

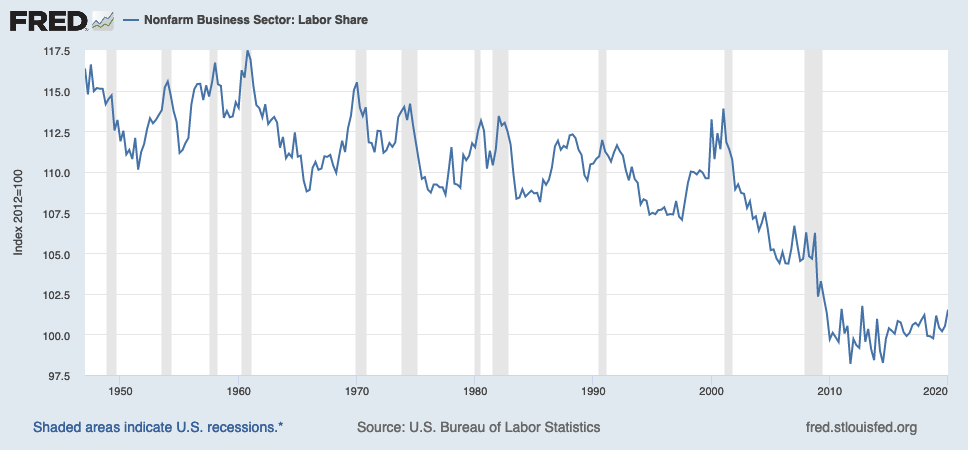

It turns out that the Fed used the purported correlation between inflation and unemployment as its primary tool for controlling inflation, ignoring all other causes of inflation. When the economy heated up and unemployment dropped, workers gained market power, and their share of national income increased. That led the Fed to raise interest rates leading to a tightening of the economy and usually a recession, as the following chart shows.

Gray bars indicate recessions.

Kelton calls this a “human sacrifice”, forcing some people out of the workforce when they want to work and can be productive. She thinks we are asking too much of the Fed. It can’t spend money into the system; only Congress can do that. All the Fed can do is change the cost of borrowing. If unemployment is too high, the Fed can make borrowing cheaper, but it can’t force anyone to borrow. Usually when unemployment is high, no one wants to borrow. I note that this was what happened after the Great Crash. The Fed cut interest rates to zero and lowered bank reserve requirements, hoping to increase money going into the economy. It didn’t work.

3. The Job Guarantee

Kelton argues that a better way to deal with unemployment is a job guarantee. Every person who wants to work should be able to get a decent job with decent pay and decent benefits. If the private sector won’t provide those jobs, the government should. [3] Kelton discusses this idea and its foundations.

It would probably be impossible for Congress to monitor the economy closely enough to manage full employment by tweaking taxes and spending. A job guarantee would act as a safety-valve and an automatic stabilizer for the economy and help solve this problem, leaving the Fed free to focus on inflation. If the private sector needs all the workers it can find them. If not, the government hires people to do jobs that need doing. There is plenty of work that needs doing, and, as Kelton pointed out elsewhere, we can always use more flowers in our parks and boulevards.

4. Preventing Inflation

So how should Congress budget knowing that the only effective constraint on spending is inflation? What would change? The way Congress currently works is that every bill that calls for expenditures gets a score from the Congressional Budget Office that assesses the impact of the expenditure on the deficit over a ten-year period. If inflation were the constraint, then the CBO would offer a score based on the probable impact of the expenditure on inflation. If the economy is, as now, operating well below its capacity for producing goods and services, the possibility of inflation would be low.

If the economy is close to capacity, either as a whole or in part related to the area of expenditures, then Congress has to make hard calls. How important is the expenditure? Can we create “fiscal space” for the expenditure with taxes? For example, in the case of the entire economy humming along, a general income tax hike would take money out of most people’s hands so they would not be buying as much, leaving room for the government to buy more. If there is a bottleneck, a more focused tax or some other step might be necessary.

Conclusion

MMT recognizes that inflation is a crucial problem. It shows how it arises and how we should protect ourselves from it.

=====

[Graphic via Grand Rapids Community Media Center under Creative Commons license-Attribution, No Derivatives]

[1] Marx said that the reserve army of labour is a necessary part of capitalism. Hmmm.

[2] This relationship is embodied in the Philips Curve. I discuss it here.

[3] Other economists favor a universal basic income. Both have the added benefit of freeing workers from abusive or irritating employers. Your family won’t starve if you walk out on a bad situation.