As I’ve noted repeatedly, there has been some abysmal reporting on the indictment, in May 2014, of 5 Chinese People’s Liberation Army hackers. Over and over reporters claim, without any caveat, that the indictment was for the theft of intellectual property, the kind of economic espionage we claim to forswear but complain about China conducting. Here are two recent examples.

David Sanger:

And when Unit 61398 of the People’s Liberation Army in China was exposed as the force behind the theft of intellectual property from American companies, the Justice Department announced the indictment of five of the army’s officers. Justice officials hailed that as a breakthrough. Inside the intelligence community and the White House, however, it was regarded as purely symbolic, and the strike on the Office of Personnel Management continued after the indictments were announced.

Elias Groll:

But nearly a year and a half after that indictment was unveiled, the five PLA soldiers named in the indictment are no closer to seeing the inside of a federal courtroom, and China’s campaign of economic espionage against U.S. firms continues.

Given that China’s hacking of US targets is so central to this week’s visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping, I wanted to return to that indictment to tease out what it actually showed. Because it — and Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes’ description of it in the lead-up to Xi’s visit — makes it clear the US is really talking about far more than IP theft.

The May 2014 indictment was mostly about monitoring negotiations and trade disputes

The indictment includes 31 charges. Just one of those charges — involving the theft of nuclear plant information from Westinghouse — is for economic espionage. Just one of those charges — involving the same theft from Westinghouse — is for theft of a trade secret. I’ll return to the Westinghouse charges in a second.

The additional charges include 9 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act violations (1-9) for breaking into various computers and stealing information, much of it to enable further hacking, 14 charges (10-23) of damaging a computer by planting malware in various computers, and 6 charges ( 24-29) of identity theft for stealing identity information associated with the targets of the attacks.

Yes, all those other 29 charges did involve hacking to obtain information. But that’s the point of what I wrote in my previous post on this: the theft isn’t the core of what we — at least explicitly — complain about China taking, the technology IP of private companies.

Here’s what PLA allegedly took from the five victims other victims, aside from Westinghouse, described in the indictment:

- SolarWind (a German company with a location in Oregon): PLA allegedly stole detailed information on SolarWind’s financial position at a time when SolarWind was litigating a dumping complaint against Chinese solar manufacturers

- US Steel: During a period when it was litigating cases against the Chinese steel industry, including against Baosteel, PLA allegedly stole data from (apparently) a sysadmin mapping USS’ computers and mobile devices

- Allegheny Technologies Incorporated: During a period when it had already started a joint venture with China’s Baosteel but also when it was in anti-dumping litigation against the company, PLA monitored ATI’s computers

- Alcoa: Immediately after Alcoa and Aluminum Corporation of China bought a 14% stake of Rio Tinto together, PLA monitored Alcoa’s computers

- US Steel Workers: During a period when it, and the steel industry, was pushing for anti-dumping action against China, PLA stole emails including strategic information

Note the last one: the Steelworkers. A bunch of business reporters are pointing to this indictment — for stealing strategic discussions from a union! — as proof that China is stealing intellectual property from US corporations and sharing it with Chinese companies.

The one case of IP theft in the indictment is reverse engineering, not independent IP theft

In addition to those four corporations and one union, there’s Westinghouse, the one victim against which DOJ actually alleged economic espionage. In 2007, Westinghouse entered into a joint venture, which included significant but carefully negotiated tech transfer. The indictment doesn’t describe which entity involved in the deal it had in mind (several companies were involved, including ones that are more independent from the state), though it is almost certainly China’s State Nuclear Power Technology Corporation, which has no illusions of independence from the state. The deal was signed with ExIm Bank support and export licensing approval. Since that time, the deal has been renegotiated over what technology would get transferred to China, and Westinghouse is still building new reactors under the deal, with the latest one opening in May 2015. A subsequent contract sold even more advanced nuke plants, with Westinghouse expecting 100% localization through the contract.

In the middle of this 8 year relationship that has and will lead to Westinghouse transferring the technology to build these plants, on May 6, 2010, the indicted hackers allegedly stole information pertaining to design specs for pipes within nuclear power plants; the indictment does not say whether those pipes were included in the technology transfer. In the economic espionage section, the indictment alleges this information got transferred for the benefit of a foreign government, China, not naming even Chinese nuclear authority SNPTC, much less any of the individual joint ventures involved in the deal. That is, even in the charge pertaining to economic espionage, the indictment does not claim this was about benefitting a specific company, but instead was about benefitting the country as a whole. And it’s not like the US can claim it doesn’t spy on specific nuclear companies in the interest of the country as a whole.

And even the Westinghouse hack included the theft of information pertaining to negotiations. The indictment notes that in the advance of Hu Jintao’s state visit to the US in 2011, as Westinghouse and SNPTC were negotiating further construction, one of the hackers targeted deliberative emails regarding these negotiations.

Some stolen e-mails described the status of the four AP1000 plants’ construction. Many other stolen e-mails, however, concerned Westinghouse’s confidential business strategies relating to [SNPTC], including Westinghouse’s (a) strategies for reaching an agreement with [SNPTC] on future nuclear power plant construction in China; and (b) discussions regarding cooperation and potential future competition with [SNPTC] in the development of nuclear power plants elsewhere around the world.

Altogether, the indictment alleges, PLA hackers took 1.4G of data, which in the grand scale of nuclear plans and negotiations is not all that much data.

All of which is to say that the economic espionage charge was a fairly minor theft in the scope of the larger indictment, constituting nowhere near the kinds of data China steals from Defense contractors, and not alleging a transfer to a specific company. It’s also, both in the scale of data stolen from US companies doing business in China (where reverse engineering is often considered the cost of doing business) and the scale of Chinese IP theft here, miniscule.

The US spies on trade disputes too

The rest of the indictment — by far the bulk of the charges — involves spying during a range of negotiations, several of them international trade disputes (though there’s also an aspect of intimidation anytime takes a trade dispute against China). We know that NSA spies on other countries involved in trade disputes, including spying on the American attorneys representing foreign governments in trade disputes. It spies rampantly in advance of larger trade negotiations. And I would be shocked if the US didn’t spy on countries considering huge arms deals with ostensibly private US companies, especially when those deals are central to the petrodollar laundering that serves as the foundation to our Middle East strategy. That is, much of what we charged China’s PLA hackers for in this indictment, the US does. And we certainly spy on individual foreign companies for US national advantage, as when we mapped out Huawei very similarly to the way China mapped out USS.

None of that’s to excuse it. But it is to say no one should expect an indictment that involved — in the grand scheme of things — miniscule amounts of IP theft and lots more amounts of trade negotiation theft to teach China a lesson about IP theft. If we want to teach China a lesson about IP theft, then maybe we should indict it for IP theft, especially the kind of IP theft outside the realm of ongoing business relations which we claim to be the real concern.

That has never happened, and reporters should stop claiming it has.

Ben Rhodes now says this is about IP theft and confidential information

All that said, in the run-up to Xi Jinping’s visit, the Administration has actually gotten slippery on what it means when it invokes this kind of theft.

In an on the record conference call Tuesday, Ben Rhodes claimed (according to the transcript), “the United States government has already engaged in law enforcement actions, for instance, that targeted Chinese entities who we believed were behind that type of activity,” referring to this 2014 indictment. He had just described the activity as, “cyber-enabled theft of confidential business information and proprietary technology from U.S. companies” and described the goals as, “the protection of intellectual property and the ability of businesses to operate without concern of cyber theft.” In addition to “proprietary technology,” Rhodes is now including the cyber-enabled theft of “confidential business information” to China’s sins.

That is, in the days before a big public discussion about cyber theft, Ben Rhodes is moving the goal posts, describing the action of concern to include both “proprietary technology” — what they’ve been talking about for years — and “confidential business information” — which definitely describes what the PLA hackers took but doesn’t describe what they usually talk about when discussing IP theft.

Interestingly, Rhodes went on to suggest China would change its ways because otherwise US corporations won’t want to do business with them. “[T]he chief reason I think the Chinese have an interest in changing some of their behavior in the cyber realm is because if they’re operating outside of established international rules and norms, they’re ultimately going to alienate businesses, including U.S. businesses who have been critical to Chinese economic growth.” This is not the model of stealing data on the F-35 from Lockheed and subcontractors, the quintessential example of IP theft people like to point to. Rather, it’s the use of hacking to reverse engineer products China is buying from US companies, something Chinese companies usually do by stealing tools used in plants in China. Maybe Rhodes is correct that companies aren’t going to rush headlong into the fastest growing market anymore knowing China will reverse engineer, including by cyber-theft, of the things they’re buying, though I think that’s only likely if China’s growth continues to skid to a halt.

Ultimately, Rhodes accused China of cheating capitalism at a more fundamental level. “[T]hat’s something that gets at the integrity of the global economy, and that’s why we’ve been so focused on this.” Which is where it gets rather farcical, because it’s not like the US as a country doesn’t do what it can to bend the rules for its companies. Plus, if the Administration wants to take on China’s cheating, there are far easier ways to do it, such as on currency.

The roll-out of some kind of mutual understanding on cyber issues this week will be interesting regardless of Rhodes’ moving of the goal posts. But that he has done so — and broadened our age-old complaint about IP theft to now include the theft of confidential business information (some, but not all of which, we also do), is itself notable.

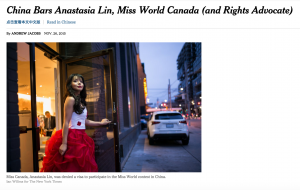

The front page of the NYT today features the story of Anastasia Lin, Chinese-born and Canadian-raised Miss Canada, who was denied entry to China for the Miss World contest.

The front page of the NYT today features the story of Anastasia Lin, Chinese-born and Canadian-raised Miss Canada, who was denied entry to China for the Miss World contest.