As I noted the other day, I’m working through documents submitted in EPIC’s FOIA for PRTT documents (see all of EPIC’s documents on this case here).

In addition to the documents released (the reports to Congress, the extensive reporting on the Internet dragnet), the government submitted descriptions of what appear to be two (possibly three) sets of documents withheld: documents pertaining to orders combining a PRTT and Section 215 order, and documents pertaining to a secret technique, which we’ll call the Paragraph 31 technique. In this post I’ll examine the “combined order” documents.

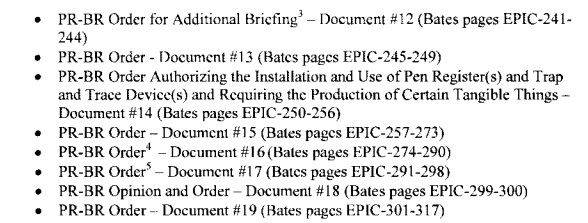

The Vaughn Index for this FOIA made it clear that a number of the documents Withheld in Full (WIF) pertained to orders combing the Pen Register and Section 215 (Business Record) authorities, as does this list from David Hardy’s second declaration.

Footnotes 3, 4, and 5 all note that these documents have already been successfully withheld in the EFF’s FOIA for Section 215 documents, and by comparing the page numbers in that Vaughn Index in that case, we can guess with some confidence that these orders are the following documents and dates:

- Document 16 is EFF 89D, dated 2/17/2006, 17 pages

- Document 17 is EFF 89K, dated 2/24/2006, 8 pages

As I’ll show, this correlates with what we can glean from the DOJ IG Reports on Section 215.

I’m less certain about Document 12. Both the EFF and ACLU Vaughn Indices show a 10/31/06 document (it is 82C in the EFF Vaughn) that is the correct length, 4 pages, that is linked with another 10/31/06 document (see 82B and 84, for example). For a variety of reasons, however, I think we can’t rule out Document 89S which appears only in the EFF FOIA (but not the ACLU FOIA), which is dated December 16, 2005 (intriguingly, the day after NYT exposed Stellar Wind), in which case the withheld portion might be the relevant 4 pages of a longer 16 page order.

Here’s how Hardy justified withholding these documents.

Documents 12 through 19 are orders and a response to orders for additional briefing issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (“FISC”) in relation to the collection of foreign intelligence information through the issuance of a PR/BR order. The FBI has withheld these documents in full because a specific investigative method and technique is discussed in all nineteen (19) [sic] documents, and each one provides various levels of detail. For example, documents 13 through 19 are FISC orders which provide details and investigative information regarding the underlying FISA application, the type and character of information to be collected from the PR/BR as well as details about the particular proceeding before the FISC. Additionally, document 68 is a response to orders for additional briefing in reference to a request for two PR/BR orders. This document discusses the method and technique in detail providing a discussion on the legal standards, citing particular case law, highlighting the legislative history as well as articulating policy considerations in utilizing the specific method and technique.

That is, FBI is withholding these documents because it doesn’t what us to know how it used PR/BR orders.

We’ve known about orders combining Pen Registers with Business Records for some time. The DOJ IG Report on Section 215 use in 2004 and 2005 (released in 2007) describes the first one.

[T]he field office had prepared an application for a FISA pen register/trap and trace order and wanted to obtain the subscriber information without using national security letters. The field office supervisor dealt directly with OIPR’s Counsel for Intelligence Policy, and they discussed the case with a FISA Court judge in person. As a result of these discussions, OIPR submitted an application for a Section 215 order for the subscriber information. The FISA Court approved two orders–one for the pen register and trap and trace devices and a Section 215 order for the related subscriber information.

The IG Report says the first of these orders was approved in February 2005 (though the December 2005 report suggests it may have been earlier, sometime during the second half of 2004, which might make it a response to changes made after the hospital confrontation).

In any case, the usage described in the 2007 IG Report is portrayed as very routine and uncontroversial.

[T]he business records portion of the application was routine and was used to obtain telecommunications subscriber information for the telephone numbers that were captured by the pen register/trap and trace order.

Here’s what the December 2006 Report to Congress says (amid several other sections redacted using b7E exemptions):

The business records portion of the combined application seeks telecommunications subscriber information for telephone numbers in conjunction with the Court-authorized installation and use of pen registers/trap and trace devices.

But even the 2007 IG Report — which only covered production until 2005 — describes some concern about the appropriateness of the collection.

OIPR had notified the FISA Court that federal judges in criminal cases had denied requests for [redacted]. Although the FISA Court agreed to approve the applications, the Court directed the government to file a supplemental brief on this issue. Prior to the hearing on the applications, OIPR revised the applications and included a footnote setting forth a summary of the relevant criminal case law regarding [redacted] and revised the order to include a direction for the government to provide the FISA Court with a supplemental briefing on this subject.

This is one reason I think the 3rd document may be the December 16, 2005 one: because to be covered in the 2007 report, it should be dated 2005, and because thus far in the DOJ IG narrative, the FISC only included an order for supplemental briefing.

The DOJ IG Report covering Section 215 use in 2006 (released in 2008) provides far more hints about a second use of the PRBR orders, beyond the uncontroversial use to get subscriber information. After a description of the conventional subscriber information use, it describes another, almost entirely redacted, use.

OIPR also used combination orders in 2005 and 2006 to obtain [redacted, with redacted footnote] (20)

Shortly thereafter, the report explains that the subscriber application of combined orders ended with the March 9, 2006 reauthorization. But in that same section, there are several other redactions that may describe a different resolution for this secret application (see for example the redaction in the last partial paragraph on 20), with an explanation of the briefing we know to be at issue.

In addition, OIPR determined that substantive amendments to the statute undermined the legal basis for which OIPR had received authorization [redacted] from the FISA Court. Therefore, OIPR decided not to request [redacted] pursuant to Section 215 until it re-briefed the issue for the FISA Court.24

24 OIPR first briefed the issue for the FISA Court in February 2006, prior to the Reauthorization Act. [redacted]

This would coincide perfectly with the two February 2006 orders the FBI is withholding in full. It may support the claim that the October 2006 document(s) pertain to combined orders, as it suggests further briefing beyond the February ones.

The DOJ IG Report later references handwritten modifications to orders referencing an opinion from the Court.

The other two handwritten modifications were made to combination orders [redacted] These orders were signed the same day the Court issued an opinion holding that [redacted]. The Court’s handwritten notations referenced the Court’s opinion. (51)

Again, these may be one or both of the 2006 opinions.

One more point: as part of DOJ’s briefing on this combined application, it submitted 4 Westlaw printouts.

Attached to document 68 are four West Law case print outs. The FBI withheld these print outs in full because they directly relate to the specific method and technique discussed in documents 12 though 19, and in the remaining parts of document 68.

This may relate to the cases referenced in the 2007 DOJ IG Report, showing that in some criminal cases, judges had found this application unsupportable. The government is trying to withhold these printouts, but EPIC is demanding the entire briefing document. That means whatever application FBI was using combined orders for, judges in some criminal cases had found it unsupported.

None of this explains what combined usage this entails (though remember that James Cole has said DOJ can get combined phone and location orders, and we know FBI uses criminal PRTT to obtain location using stingrays). But it suggests pretty clearly that there was (and may still be) a second, more controversial use of PRBR orders.

Update: Two pieces of evidence suggesting this “combined” use was for real-time cell location from cell providers.

First, note that changes in the law meant the government could no longer use this combined application. One thing that got added in 2006 (and approved in the conference report on December 14, 2005, two days before one of the documents withheld in the EFF FOIA) was language limiting the use of Section 215 to things that could be obtained with a grand jury subpoena.

(D) may only require the production of a tangible thing if such thing can be obtained with a subpoena duces tecum issued by a court of the United States in aid of a grand jury investigation or with any other order issued by a court of the United States directing the production of records or tangible things;

And Patrick Toomey pointed to three 2005 decisions rejecting government “hybrid” requests to get real time cell location data by yoking a Pen Register and a 2703(d) order as possible candidates to be the Westlaw cases the government is withholding (see here, here, and here). (WaPo highlighted the importance of these 2005 decisions some months ago).

The language from the rulings makes it clear how easily the government might use the same combination, of a FISA PRTT and a Section 215 order, to get real-time location data.

Having concluded that prospective cell site data is properly categorized as tracking device information under § 3117, the question arises whether such data may not also be obtainable under other provisions of the ECPA. In other words, do the four broad categories of the ECPA overlap, such that location information obtainable from a § 3117 tracking device is simultaneously obtainable under the Wiretap Act, the SCA, or the Pen/Trap Statute? The answer to this question is clearly “no.”

[snip]

The government nevertheless contends that a pen/trap order, when combined with a § 2703(d) order, is sufficient authority to collect prospective cell site data. This dual or “hybrid” authority argument is based on a subtle concatenation of three different statutes. The argument proceeds as follows: (1) prospective cell site data falls within the PATRIOT Act’s expanded definitions of “pen register” and “trap and trace device”[17] because carriers use cell site data for “routing” calls to and from their proper destination; (2) CALEA amended the law to prevent disclosure of a caller’s physical location “solely” pursuant to a pen/trap order, so the government need only have some additional authority besides the Pen/Trap Statute to gather prospective cell site information; (3) the SCA provides that additional authority, because cell site data is non-content subscriber information obtainable upon a “specific and articulable facts” showing under § 2703(d); and (4) completing the circle, cell site data authorized by a § 2703(d) order may be collected prospectively by virtue of the forward-looking procedural features of the Pen/Trap Statute. By mixing and matching statutory provisions in this manner, the government concludes that cell site data enjoys a unique status under electronic surveillance law a new form of electronic surveillance combining the advantages of the pen/trap law and the SCA (real-time location tracking based on less than probable cause) without their respective limitations.

[snip]

The government’s third premise, that § 2703(d) authorizes collection of prospective cell site data has already been considered and rejected above in part 4.

The sum of these questionable premises is no greater than its defective parts. The most glaring difficulty in meshing these disparate statutory provisions is that with a single exception they do not cross-reference one another. The Pen/Trap Statute does not mention the SCA or CALEA; SCA § 2703 does not mention CALEA or the Pen/Trap Statute; and the CALEA proviso does not mention the SCA. CALEA does refer to the Pen/Trap Statute, but only in the negative sense of disclaiming its applicability. Surely if these various statutory provisions were intended to give birth to a new breed of electronic surveillance, one would expect Congress to have openly acknowledged paternity somewhere along the way.[20] This is especially so given that no other form of*765 electronic surveillance has the mixed statutory parentage that prospective cell site data is claimed to have.

[snip]

The government’s hybrid theory, while undeniably creative, amounts to little more than a retrospective assemblage of disparate statutory parts to achieve a desired result. Viewing each statute in proper temporal perspective, there is simply no reason to believe that Congress intended to treat location monitoring of cell phones as an exceptional type of electronic surveillance. While Congressional enactments are sometimes difficult to decipher, employing such a three-rail bank shot to create a new category of electronic surveillance seems almost perverse. Had Congress truly intended such an outcome, there were surely more direct avenues far less likely to confound and mislead judicial inquiry.

It seems the two things, taken in tandem, would have made it much more difficult to make this argument, even in secret.