The other day I looked at an exchange between Ron Wyden and Jim Comey that took place in January 2014, as well as the response FBI gave Wyden afterwards. I want to return to the reason I was originally interested in the exchange: because it reveals that FBI, in addition to obtaining cell location data directly from a phone company or a Stingray, will sometimes get location data from a mobile app provider.

The other day I looked at an exchange between Ron Wyden and Jim Comey that took place in January 2014, as well as the response FBI gave Wyden afterwards. I want to return to the reason I was originally interested in the exchange: because it reveals that FBI, in addition to obtaining cell location data directly from a phone company or a Stingray, will sometimes get location data from a mobile app provider.

I asked Magistrate Judge Stephen Smith from Houston whether he had seen any such requests — he’s one of a group of magistrates who have pushed for more transparency on these issues. He explained he had had several hybrid pen/trap/2703(d) requests for location and other data targeting WhatsApp accounts. And he had one fugitive probation violation case where the government asked for the location data of those in contact with the fugitive’s Snapchat account, based on the logic that he might be hiding out with one of the people who had interacted with him on Snapchat. The providers would basically be asked to to turn over the cell site location information they had obtained from the users’ phone along with other metadata about those interactions. To be clear, this is not location data the app provider generates, it would be the location data the phone company generates, which the app accesses in the normal course of operation.

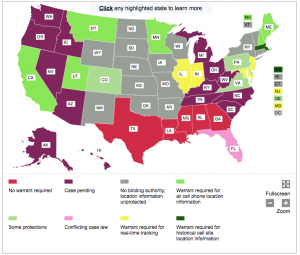

The point of getting location data like this is not to evade standards for a particular jurisdiction on CSLI. Smith explained, “The FBI apparently considers CSLI from smart phone apps the same as CSLI from the phone companies, so the same legal authorities apply to both, the only difference being that the ‘target device’ identifier is a WhatsApp/Snapchat account number instead of a phone number.” So in jurisdictions where you can get location data with an order, that’s what it takes, in jurisdictions where you need a probable cause warrant, that’s what it will take. The map above, which ACLU makes a great effort to keep up to date here, shows how jurisdictions differ on the standards for retrospective and prospective location information, which is what (as far as we know) will dictate what it would take to get, say, CSLI data tied to WhatsApp interactions.

Rather than serving as a way to get around legal standards, the reason to get CSLI from the app provider rather than the phone company that originally produces it is to get location data from both sides of a conversation, rather than just the target phone. That is, the app provides valuable context to the location data that you wouldn’t get just from the target’s cell location data.

The fact that the government is getting location data from mobile app providers — and the fact that they comply with the same standard for CSLI obtained from phones in any given jurisdiction — may help to explain a puzzle some have been pondering for the last week or so: why Facebook’s transparency report shows a big spike in wiretap warrants last year.

[T]he latest government requests report from Facebook revealed an unexpected and dramatic rise in real-time interceptions, or wiretaps. In the first six months of 2015, US law enforcement agencies sent Facebook 201 wiretap requests (referred to as “Title III” in the report) for 279 users or accounts. In all of 2014, on the other hand, Facebook only received 9 requests for 16 users or accounts.

Based on my understanding of what is required, this access of location data via WhatsApp should appear in several different categories of Facebook’s transparency report, including 2703(d), trap and trace, emergency request, and search warrant. That may include wiretap warrants, because this is, after all, prospective interception, and not just of the target, but also of the people with whom the target communicates. That may be why Facebook told Motherboard “we are not able to speculate about the types of legal process law enforcement chooses to serve,” because it really would vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and possibly even judge to judge.

In any case, we can be sure such requests are happening both on the criminal and the intelligence side, and perhaps most productively under PRISM (which could capture foreign to domestic communications at a much lower standard of review). Which, again, is why any legislation covering location data should cover the act of obtaining location data, whether via the phone company, a Stingray, or a mobile app provider.