Last week, lawyers from Jones Day representing the Trump campaign submitted a response to a lawsuit by two Democratic donors and a DNC employee (the case is referred to as Cockrum after donor Roy Cockrum) that presents an interesting, but imperfect, preview of any defense of a Trump conspiracy and/or a WikiLeaks charge in the election hack-and-leak.

Effectively, the Democrats attempt to hold the Trump campaign responsible for having their private information (social security numbers in the case of the donors and more personal conversations in the case of DNC employee Scott Comer) posted in the emails released by WikiLeaks on July 22, 2016. They do so by arguing that the Trump campaign conspired with agents of Russia, agreeing to provide policy considerations in exchange for the assistance presented by the email release, which therefore makes them parties to the injury associated with the hack-and-leak.

The campaign isn’t responsible for information released as part of their conspiracy because the First Amendment protects it

In response, the Trump campaign (represented by Jones Day, and therefore by more competent lawyers than some of the clowns representing the president in the Mueller investigation) only secondarily deny the campaign entered into a conspiracy with the Russians as governed by the laws invoked by plaintiffs (you should not take this emphasis as admission of guilt in a conspiracy, but rather the most efficacious way of defeating the lawsuit). As a primary defense, they point to First Amendment precedent to argue two things: First, the campaign can’t be held responsible for the theft of information because they only sought the dissemination of already stolen documents — they had nothing to do with the theft of the documents, the campaign argues.

In Bartnicki v. Vopper, 532 U.S. 514 (2001), the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment protects a speaker’s right to disclose stolen information if (1) the speaker was “not involved” in the acquisition and (2) the disclosure deals with “a matter of public concern.” Id. at 529, 535. There, union leaders spoke on the phone about using violence against school-board members to influence salary negotiations. Id. at 518–19. An unknown person secretly intercepted the call and shared the illegal recording with a local radio host, who played it on his show. Id. at 519. The Court ruled that the First Amendment protected the radio broadcast, because the host “played no part in the illegal interception” and “the subject matter of the conversation was a matter of public concern.” Id. at 525. The Court reasoned that “state action to punish the publication of truthful information seldom can satisfy constitutional standards.” Id. at 527. The state has an interest in deterring theft of information, but it must pursue that goal by imposing “an appropriate punishment” on “the interceptor”—not by punishing a speaker who was “not involved in the initial illegality.” Id. at 529. The state also has an interest in protecting “privacy of communication,” but “privacy concerns give way when balanced against the interest in publishing matters of public importance.” Id. at 533–34. In short, “a stranger’s illegal conduct does not suffice to remove the First Amendment shield from speech about a matter of public concern.” Id. at 535.

“An opposite rule”—under which a speaker may be punished for truthful disclosures on account of a “defect in the chain of title”—“would be fraught with danger.” Boehner v. McDermott, 484 F.3d 573, 586 (D.C. Cir. 2007) (opinion of Sentelle, J., joined by a majority of the en banc court). “U.S. newspapers publish information stolen via digital means all the time.” Jack L. Goldsmith, Uncomfortable Questions in the Wake of Russia Indictment 2.0 (July 16, 2018).1 Indeed, they “openly solicit such information.” Id. Punishing “conspiracy to publish stolen information” “would certainly narrow protections for ‘mainstream’ journalists.” Id.

The Campaign satisfies the first part of Bartnicki’s test: It “played no part in the illegal interception.” Bartnicki, 532 U.S. at 525. That is clear from Plaintiffs’ factual theory: “Defendants entered into an agreement with other parties, including agents of Russia and WikiLeaks, to have information stolen from the DNC publicly disseminated in a strategic way.” (Am. Compl. ¶ 16) (emphasis added). The complaint reinforces that theory on every page: “the publication of hacked information pursuant to the conspiracy” (id. ¶ 20); “conspiracy … to disseminate information” (id. ¶ 78); “extracting concessions … in exchange for the dissemination of the information” (id. ¶ 149); “an agreement to disseminate the hacked DNC emails”) (id. at 42); “motive to coordinate regarding such dissemination” (id. ¶ 153); “an agreement regarding the publication” (id. ¶ 154); “agreed … to publicly disclose” (id. ¶ 296) (all emphases added).

In a key move, the response points to the chronology (they incorrectly say) the plaintiffs lay out to show that the Campaign didn’t enter into a conspiracy with the Russians until after the theft had already taken place.

That is no surprise. Given Rule 11, Plaintiffs could not have alleged the Campaign’s involvement in the initial hack. According to Plaintiffs’ own account, Russian intelligence hacked the DNC’s networks “in July 2015,” and gained access to email accounts “by March 2016.” (Id. ¶ 86.) But the Campaign supposedly became motivated to work with Russia only in “the spring and summer of 2016” (id. at 25), and supposedly entered into the agreement in “secret meetings” in “April,” “May,” “June,” and “July” 2016 (id. ¶¶ 89–104). In other words, Plaintiffs themselves say that the alleged conspiracy was formed after the hack and after the acquisition of the emails—so that the Campaign could not have participated in the initial theft.

From there, the Campaign shifts to the second part of the First Amendment argument: what they encouraged the Russians (and WikiLeaks) to publish was a matter of public concern.

The Campaign also satisfies the second part of Bartnicki’s test: the disclosure deals with “a matter of public concern.” Bartnicki, 532 U.S. at 525. Whether speech deals with issues of public concern is “a matter of law.” Snyder v. Phelps, 580 F.3d 206, 220 (4th Cir. 2009). “Speech deals with matters of public concern when it can be fairly considered as relating to any matter of political, social, or other concern to the community, or when it is a subject of legitimate news interest.” Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 453 (2011) (citations and quotation marks omitted). A court applying this test must examine the “content, form, and context” of the speech. Id.

Courts judge the public character of a disclosure in the aggregate, not line by line. Regardless of whether the particular sentence complained about is itself of public concern, the disclosure is constitutionally protected if the disclosure as a whole deals with a matter of public concern. For example, in Bartnicki, leaders of a teachers’ union spoke on the phone about “blow[ing] off [school-board members’] front porches” to influence salary negotiations. 532 U.S. at 519. Even though the threat to “blow off” porches was not itself speech about public issues, the First Amendment protected the disclosure because the host made it while “engaged in debate about” teacher pay—“a matter of public concern.” Id. at 535. The “public concern” test thus turns on the broader context of the disclosure, not the nature of the specific fact disclosed.

To substantiate their “public concern” defense, the response points to (and includes as exhibits) a handful emails out of the tens of thousands dumped in just the DNC release and some bad press coverage, and argues that because WikiLeaks has a policy of not redacting emails, the information that damaged the plaintiffs just came out along with this public concern information.

These emails revealed important information about the Clinton Campaign and Democratic Party. For example:

- The emails revealed DNC officials’ hostility toward Senator Sanders. DNC figures discussed portraying Senator Sanders as an atheist, because “my Southern Baptist peeps would draw a big difference between a Jew and an atheist.” (Ex. 1.) They suggested pushing a media narrative that Senator Sanders “never ever had his act together, that his campaign was a mess.” (Ex. 2.) They opposed his push for additional debates. (Ex. 3.) They complained that he “has no understanding” of the Democratic Party. (Ex. 4.)

- According to The New York Times, “thousands of emails” between donors and fundraisers revealed “in rarely seen detail the elaborate, ingratiating and often bluntly transactional exchanges necessary to harvest hundreds of millions of dollars from the party’s wealthy donor class.” These emails “capture[d] a world where seating charts are arranged with dollar totals in mind, where a White House celebration of gay pride is a thinly disguised occasion for rewarding wealthy donors and where physical proximity to the president is the most precious of currencies.” (Ex. 5.)

- The emails revealed the coziness of the relationship between the DNC and the media. For example, they showed that reporters would ask DNC to pre-approve articles before publication. (Ex. 6.) They also showed DNC staffers talking about giving a CNN reporter “questions to ask us.” (Ex. 7.)

- The emails revealed the DNC’s attitudes toward Hispanic voters. One memo discussed ways to “acquire the Hispanic consumer,” claiming that “Hispanics are the most brand loyal consumers in the World” and that “Hispanics are the most responsive to ‘story telling.’” (Ex. 8.) Another email pitched “a new video we’d like to use to mop up some more taco bowl engagement.” (Ex. 9.)

WikiLeaks, however, did not redact the emails, so the publication also included details that Plaintiffs describe as private.

In this scenario, even assuming the Trump campaign did enter a conspiracy with the Russians, the plaintiffs in this lawsuit were just collateral damage to disclosures protected by the First Amendment.

The conspiracy to hurt individual Democratic donors defense

As noted, the defense against the claim that the campaign entered into a conspiracy with the Russians is only a secondary part of the defense here. Perhaps that’s because this part of the defense is far weaker than the First Amendment part.

As part of it, the response notes that the plaintiffs would have had to enter into a conspiracy with the goal and the state of mind laid out by the two laws primarily cited by plaintiffs, to intimidate voters and to intentionally inflict harm on plaintiffs. Once again, this part of the argument treats the plaintiffs as collateral damage to the goals of embarrassing the DNC effectuated by the publication of materials by WikiLeaks, which has a policy of not redacting anything in its releases.

Plaintiffs do not plausibly allege these states of mind. For one thing, Plaintiffs allege that the object of the purported conspiracy was to promote the Trump Campaign and to embarrass the DNC and the Clinton Campaign. (Am. Compl. ¶ 190.) They do not allege facts showing that the Campaign even knew of Mr. Comer, Mr. Cockrum, or Mr. Schoenberg, much less that Campaign officials met with Russian agents for the purpose of disclosing these individuals’ social security numbers, gossip, and stomach-flu symptoms.

For another thing, Plaintiffs fail to address (let alone refute) the “obvious alternative explanation” for the disclosure of their emails (Iqbal, 556 U.S. at 682): WikiLeaks’ “accuracy policy,” under which WikiLeaks does not redact or “tamper with” the documents it discloses. (Ex. 10.) The upshot is that Plaintiffs do not plausibly allege that the Campaign acted with the purpose of intimidating Plaintiffs; do not plausibly allege that the Campaign acted with the specific intent to disclose Plaintiffs’ allegedly private emails; and do not plausibly allege that the Campaign acted with knowledge that the WikiLeaks email collection included Plaintiffs’ allegedly private emails.

It’s the other part of the conspiracy defense where the response is dangerously weak, given the possibility that Mueller will roll out another indictment providing more detail on negotiations between the campaign and Russia (which plaintiffs could then add in an amended complaint). Here, the campaign argues only that the plaintiffs haven’t shown proof of a conspiracy because they have not yet pointed to evidence that the campaign sought the DNC emails specifically, including the details that allegedly damaged the plaintiffs.

[T]he Amended Complaint fails to plausibly allege that the Campaign conspired with or aided and abetted the publishers of the DNC emails. Plaintiffs allege a series of meetings between the Campaign and Russian agents in 2016. (Id. ¶ 15.) But Plaintiffs do not allege that any of the meetings in any way concerned the DNC emails, much less the information about Plaintiffs contained in those emails. The allegation that people met to discuss something does not raise a plausible inference that they met to discuss collaborative efforts to release specific emails hacked from the DNC to influence an election, much less to intimidate or embarrass Plaintiffs. Cf. Twombly, 550 U.S. at 567 n.12 (regular meetings do not suggest conspiracy).

This argument may be sufficient for this civil suit, but for a number of reasons, such an argument would be totally insufficient in a criminal case. For starters, there likely is evidence, not least obtained from Paul Manafort’s cooperation, that the campaign had some idea of what they might get in exchange for entering into a quid pro quo with the Russians. As it is, Jones Day is utterly silent about Don Jr’s, “If it’s what you say I love it especially later in the summer” email, which reflects some expectation, already by June 3, 2016, of what the campaign would get for entering into a conspiracy, even though plaintiffs quote it in their complaint.

But also, the conspiracy charged in a criminal indictment would allege a different goal — in part, the embarrassment of the DNC and support of the Trump campaign that the campaign response stops far short of denying. So while with respect to the suit brought by these plaintiffs, the argument that the defendants did not have the mindset of trying to intimidate voters or damage the plaintiffs, if and when Mueller charges a conspiracy, it will argue a different mind set, to defraud the US’ election integrity, in part to obtain a thing of value from the Russians. And that mindset is going to be much easier to prove.

This response does next to nothing to deny that mindset.

Instead, much later in the response (as part of an argument that plaintiffs can’t claim a conspiracy to violate campaign finance laws because the FEC preempts it), the campaign does address what might be one defense in a criminal indictment charging that the Trump team conspired with Russia with the goal of obtaining illegal campaign donations in the form of dirt on Hillary. The response argues that such released emails do not constitute a thing of value, but are instead protected political speech.

Plaintiffs in all events fail to establish a conspiracy to violate any federal campaign-finance law. Plaintiffs assert that federal law prohibits foreign nationals from making “a contribution or donation of money or other thing of value” in connection with an election, 52 U.S.C. § 30121(a), and that “Defendant’s co-conspirators … contributed a ‘thing of value’ … in the form of the dissemination of hacked private emails” (Am. Compl. ¶ 215). This assertion is incorrect. For one, there is a fundamental difference between contributing a thing of value and engaging in pure political speech. Pure political speech constitutes “direct political expression”; in contrast, “while contributions may result in political expression if spent by a candidate or association to present views to the voters, the transformation of contributions into political debate involves speech by someone other than the contributor.” Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 21–22 (1976). The disclosure of information about a political party is pure political speech, not a political contribution. The disclosure itself directly expresses political messages; unlike money, it does not need to be transformed into a political message by somebody else.

For another, treating a disclosure of information as a “contribution” would violate the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has held that the First Amendment guarantees Americans the right to receive political speech from foreigners. Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301, 306 (1965). Yet under Plaintiffs’ theory, it would be illegal to solicit political information from a foreign national, because the provision of such information would amount to a “contribution.” For example, “if the Clinton campaign heard that Mar-a-Lago was employing illegal immigrants in Florida and staffers went down to interview the workers, that would be a crime.” Eugene Volokh, Can it be a crime to do opposition research by asking foreigners for information? (July 27, 2017).2 “Or say that Bernie Sanders’s campaign heard rumors of some misconduct by Clinton on her trips abroad—it wouldn’t be allowed to ask any foreigners about that.” Id. The First Amendment does not tolerate such results.

This claim, if it were substantiated, would have repercussions across Mueller’s work, extending to the Internet Research Agency indictment (indeed, Concord Consulting is trying to make similar arguments, though not as brazenly suggesting that foreigners have a First Amendment right to weigh in on our elections).

Yet, as I’ve noted, Mueller has already collected evidence of how much a similar campaign to the one the Russians conducted would cost a campaign, in the form of the spooked up Psy-Group campaign offered by Israelis and Gulf supporters: $3.31 million. That is, Mueller has the evidence to show that the Russians did not just release the information, but engaged in an entire social media campaign to maximize the value of the information they released, and that information goes beyond simple publication to the stuff that political consultants charge real money for.

The other problems with this defense

There is far more to the campaign’s defense (notably, extensive arguments about whether state or federal law applies to particularly parts of the complaint, and if it’s state law, whether it’s Maryland, New Jersey, and Tennessee as plaintiffs argue, or Virginia and New York as defendants do) than what I’ve laid out, and this suit would be a challenge in any case. But there are other problems with the defense.

In a piece on this response, Floyd Abrams argues that there are key differences between the primary First Amendment precedent on which the defense relies and this case. For example, the Bartnicki case focused on material the entirety of which was in the public interest, whereas the bulk of what the Russians gave WikiLeaks is not.

[T]he entirety of the wiretapped recording in Bartnicki was of undoubted public interest while some portions of the purloined DNC documents had a special claim to being of no sustainable public interest while inflicting substantial potential privacy harm—including social security numbers sent to the DNC which WikiLeaks, as it has repeatedly chosen to do, decided to make public.

Jones Day may well realize this is a weak part of their argument, as they return to WikiLeaks’ failure to redact information that had no public interest in a number of ways. At one point, they argue that if WikiLeaks redacted information some information of public interest might get withheld as part of the process.

To establish public-disclosure liability, a plaintiff must show that the facts at issue are not “of legitimate concern to the public”—in other words, that the facts are not “of the kind customarily regarded as ‘news.’” Second Restatement § 652D & comment g. Like the First Amendment test, the tort-law test requires courts to analyze speech “on an aggregate basis.” Alvarado v. KOB-TV, LLC, 493 F.3d 1210, 1221 (10th Cir. 2007). A publisher does not have to “parse out concededly public interest information” “from allegedly private facts.” Id. That is because redactions would undermine the “credibility” of a disclosure, causing the public to doubt its accuracy. Ross v. Midwest Commc’ns, Inc., 870 F.2d 271, 275 (5th Cir. 1989). Further, requiring publishers to redact—“to sort through an inventory of facts, to deliberate, and to catalogue”—“could cause critical information of legitimate public interest to be withheld until it becomes untimely and worthless to an informed public.” Star-Telegram, Inc. v. Doe, 915 S.W.2d 471, 475 (Tex. 1995).

At another point, they argue (this is one of their most ridiculous arguments) that WikiLeaks is just an intermediary that the Russians used to post injurious messages.

Under section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (47 U.S.C. § 230), a state may impose liability on “the original culpable party who posts [tortious] messages,” but not on “companies that serve as intermediaries for other parties’ potentially injurious messages.” Zeran v. America Online, 129 F.3d 327, 330–31 (4th Cir. 1997). As a result, a website that provides a forum where “third parties can post information” is not liable for the third party’s posted information. Klayman v. Zuckerberg, 753 F.3d 1354, 1358 (D.C. Cir. 2014). Since WikiLeaks provided a forum for a third party (the unnamed “Russian actors”) to publish content developed by that third party (the hacked emails), it cannot be held liable for the publication.

And the insistence that WikiLeaks is known not to redact information may hurt the Trump campaign if it gets that far.

Abrams also points to how entering into a conspiracy might change the legal liability of the Trump campaign.

[T]he Bartnicki defendants were at all times entirely independent of the person who surreptitiously made the wiretapped recording available to it while the Trump campaign is accused in Cockrum of conspiring with its alleged Russian source after the information had been hacked to make the information public.

Even for the purpose of this lawsuit, the claim that the Trump campaign entered into a conspiracy only after the information had been hacked may not be sustainable. After all, George Papadopoulos learned the Russians were going to release emails, of some sort (even if he believed they were Hillary server emails rather than DNC ones), well before the Russians were ejected from the DNC servers a month later. The Russians first contacted the Trump campaign about this conspiracy on April 26, 2016, after they had stolen the Podesta emails in March; but the DNC emails that are the subject of this lawsuit weren’t exfiltrated, at least according to the GRU indictment, until a month later.

Between on or about May 25, 2016 and June 1, 2016, the Conspirators hacked the DNC Microsoft Exchange Server and stole thousands of emails from the work accounts of DNC employees.

So Papadopoulos’ responsiveness might be enough to sustain a claim that the Trump campaign was engaged in this conspiracy before the emails in question were stolen. Indeed, this paragraph from the response (cited above) falsely claims that the plaintiffs suggested the theft ended in March.

Plaintiffs could not have alleged the Campaign’s involvement in the initial hack. According to Plaintiffs’ own account, Russian intelligence hacked the DNC’s networks “in July 2015,” and gained access to email accounts “by March 2016.” (Id. ¶ 86.) But the Campaign supposedly became motivated to work with Russia only in “the spring and summer of 2016” (id. at 25), and supposedly entered into the agreement in “secret meetings” in “April,” “May,” “June,” and “July” 2016 (id. ¶¶ 89–104). In other words, Plaintiffs themselves say that the alleged conspiracy was formed after the hack and after the acquisition of the emails—so that the Campaign could not have participated in the initial theft.

Here’s what the complaint really says:

In order to defeat Secretary Clinton and help elect Mr. Trump, hackers working on behalf of the Russian government broke into computer networks of U.S. political actors involved in the 2016 election, including the DNC and the Clinton Campaign. Elements of Russian intelligence gained unauthorized access to DNC networks in July 2015 and maintained that access until at least June 2016. By March 2016, the Russian General Staff Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU) gained unauthorized access to DNC networks, DCCC networks, and the personal email accounts of Democratic Party officials and political figures.

By May 2016, the GRU had copied large volumes of data from DNC networks, including email accounts of DNC staffers. Much of the GRU’s activity within the DNC networks took place between March and June 2016, at the very same time its agents were intensifying their outreach to and securing meetings with agents of the Trump Campaign.

[snip]

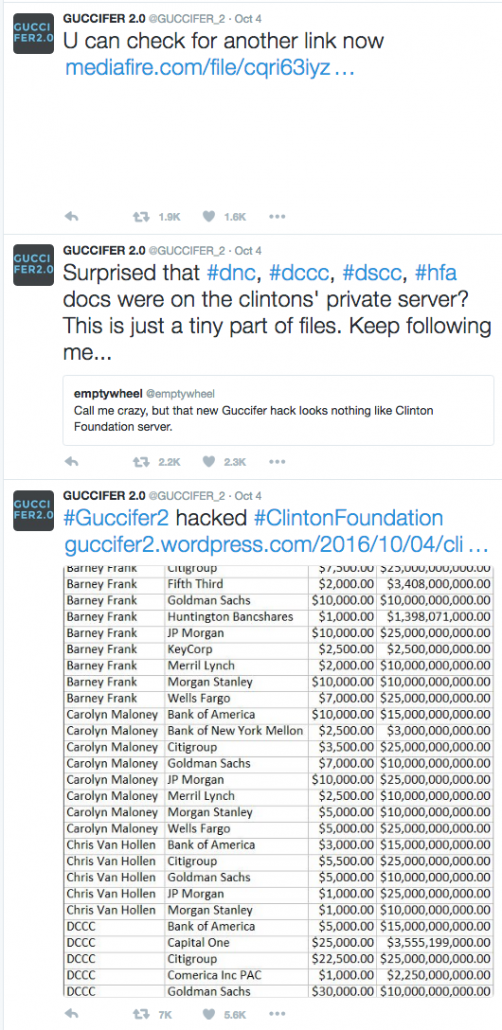

According to the indictment, “in and around April 2016, the Conspirators began to plan the release of materials stolen from the Clinton Campaign, DCCC, and DNC.” And “in or around June 2016,” when the Trump Campaign was taking meetings with Russian agents to “get information on an opponent,” the indicted Russians and their coconspirators began to “stage[] and release[]” the stolen emails.

All that said, if the plaintiffs are relying on the June 9 meeting to establish the conspiracy, or even Don Jr’s June 3 email enthusiastically responding to Rob Goldstone’s offer, the campaign can argue in this suit that the actual theft of the emails in question — the DNC emails revealing the donors social security numbers and Comer’s embarrassing comments — were, according to the public record, already stolen by the time the campaign entered into the conspiracy.

But that’s not going to work if Mueller charges a criminal conspiracy. That’s true, in part, because the criminal conspiracy would include the social media part of the Russian assistance, which continued well after the June 9 meeting (the plaintiffs here couldn’t argue the social media exploitation hurt them because the emails including the information damaging to them wasn’t promoted by Russian social media actors). It would also include the DCCC releases, which led to the provision of opposition research to Republican operatives.

Indeed, even the hacking continued after the June 9 meeting. As the plaintiffs pointed out, on July 27, Russian hackers even seemed to respond directly to Trump’s request for assistance.

191. On July 27, 2016, during the Democratic National Convention, Mr. Trump held a press conference in Florida. During his remarks, Mr. Trump called on Russia to continue its cyberattacks, stating, “Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you’re able to find the 30,000 [Secretary Clinton] emails that are missing.” Although the Trump Campaign—and later, then-White House press secretary Sean Spicer—claimed that Mr. Trump was “joking,” when Mr. Trump was asked at the time to clarify his remark and whether he was serious, Mr. Trump stated: “If Russia or China or any other country has those emails, I mean, to be honest with you, I’d love to see them.”

192. According to the July 13, 2018 indictment of twelve Russian nationals filed by the Special Counsel, agents of the Russian government attempted that same day—July 27, 2016— “to spearfish for the first time email accounts at a domain hosted by a third-party provider and used by Clinton’s personal office.” In other words, on the day that Mr. Trump publicly said that he hoped Russia would be able to find missing emails related to Secretary Clinton, Russian intelligence for the first time attempted to hack email accounts on Secretary Clinton’s own server.

That particular hack was not successful, but a hack of the Democrats’ AWS hosted analytics program in September was; see ¶34. As I understand it, the targeting of Hillary’s campaign went on in a series of waves, and those waves might be shown to correlate to Trump’s requests for assistance.

So, absent proof that someone in the campaign encouraged Papadopoulos after having learned about the emails in April, the plaintiffs in this suit will struggle to show that Russian hacking of the emails that injured them took place after Trump’s campaign entered into the conspiracy. But Mueller won’t have that problem. And all that’s before the Peter Smith operation, which asked for assistance from Guccifer 2.0 and reached out to presumed Russian hackers to obtain information from Hillary’s home server. Plus, that’s all separate from the social media campaign which continued to benefit the Trump campaign up to the election.

The ironies of a First Amendment defense

There’s a detail about this response, however, that (relying as it does on a strong First Amendment defense) deserves more attention. The response claims that the entire purpose of this suit suit is to obtain discovery on the President on a number of topics — notably his tax returns and business relationships — that Democrats have been unable to fully pursue elsewhere.

The object of this lawsuit is to launch a private investigation into the President of the United States. The Amended Complaint already foreshadows discovery into the President’s “tax returns” (Am. Compl. ¶ 238), his “business relationships” (id.), his conversations with “Director Comey” (id. ¶ 251), and on and on.

Much later, in the conspiracy section, in an argument that seems designed for Brett Kavanaugh’s review, the response argues that plaintiffs need a more plausible claim to be able to get discovery from the President.

Rule 8 requires a complaint to state a “plausible” claim for relief. Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 678 (2009). A complaint satisfies this standard if its “factual content” raises a “reasonable inference” that the defendant engaged in the misconduct alleged. Id. at 678. This requirement protects defendants against “costly and protracted discovery” on a “largely groundless claim.” Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 558 (2007). This protection is essential here, where Plaintiffs’ explicit goal is to burden the President with discovery. The President’s “unique position in the constitutional scheme” requires him to “devote his undivided time and attention to his public duties.” Clinton v. Jones, 520 U.S. 681, 697–98 (1997). Courts must thus ensure that plaintiffs do not use “civil discovery” on “meritless claims” to interfere with his responsibilities. Cheney v. U.S. District Court, 542 U.S. 367, 386 (2004).

It’s only after making the claim that this suit is all about obtaining public interest information such as the President’s tax returns that the campaign makes an argument justifying the release of all this information in the name of public interest.

According to the logic Jones Day lays out here, the Democrats’ mistake was in not finding foreign hackers to steal and then publish Trump’s tax returns.

As I disclosed in July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.