The FISA Court Accepted 9% Fewer Combined Applications Last Year

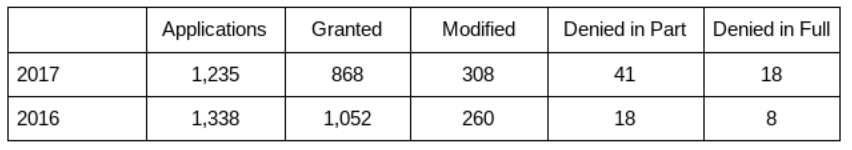

The FISA Court released its second annual report on approval rates today (the obligation to produce such a report dates to 2015 and it produced a partial report covering that year). It shows that the FISA Court rejected and modified far more joint applications last year than the prior year, with just a 70% complete approval last year as compared to a 79% complete approval the year before, as reflected in this table.

Approval rates for combined orders, 2017 versus 2016

These are for combined orders, meaning the government wants to collect both data in motion and (collect stored data and/or conduct a physical search). Modifications usually mean additional reporting and/or minimization procedures (meaning the government had to treat the collected data with additional care). An order denied in part might prohibit the collection on one of the selectors submitted to the court, but not a bunch of other ones. An order denied in full would represent a complete rejection of a preliminary order (these won’t show up on DOJ’s numbers because those are fluffed to look good).

There are several things that might explain these numbers. First, the rising modification number might mean the government is using new techniques that present additional privacy concerns — accessing cell phones are a likely one, especially given the Riley SCOTUS precedent. Hacking is another technique that might pose specific privacy concerns, or accessing entire servers.

The denied in part number likely stems from the government asking to surveil selectors that are more attenuated from the actual target. The rejections might reflect individual selectors for which the FISC didn’t agree the government had shown probable cause the selector was being used by an agent of a foreign power.

Most alarming, though, is the rise in outright rejections, from 8 to 18. This suggests the government is trying to wiretap and otherwise surveil people as agents of a foreign power that the FISC doesn’t agree are such.

And all this happened at a time when the government submitted fewer overall combined applications. Remember, the government can and sometimes does take its wiretapping elsewhere if the FISC rejects a practice. I’ll do a follow-up post describing why this report may reflect that has happened.

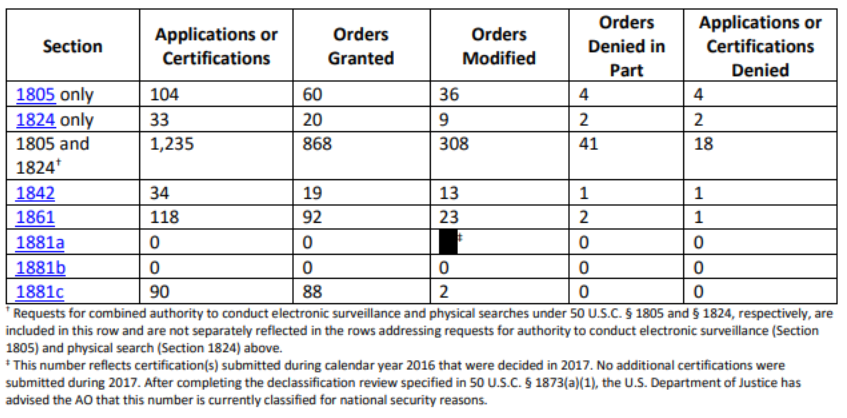

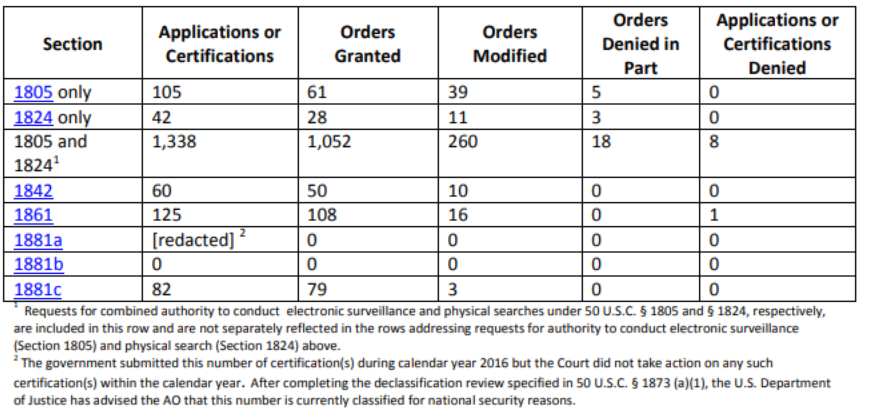

Here’s this year’s report, covering 2017, and last year’s report, covering 2016. This post provides background on the requirement and how these reports differ from the required DOJ report. The full tables from the two reports are below. They show an increased rate of modifications for 1861, which are 215 orders, as well.