Snowden Needs a Better Public Interest Defense: Disposing of the Journalist Filter

Some weeks ago, I wrote what was meant to be the second part of a three part review of Edward Snowden’s book, Permanent Record, in which I argued that his use of the Bildungsroman genre raised more questions than it answered about the timing of the moment he came to decide to reveal NSA’s files. I argued that the narrative did not present a compelling story that he had the maturity or the knowledge of the NSA’s files needed to sustain a public interest defense before the time he decided to take those files.

I’ve been struggling to write what was meant to be the first part of that review. That first part was meant to assess what I will treat as Snowden’s “cosmopolitan defense,” showing that his leaks have since been judged by neutral authorities to have revealed legal or human rights violations. As that first part has evolved, it has shifted into a more of a reflection on the failures of the surveillance community as a whole (and therefore my own failures) and of limits to an investment in whistleblowing as exposure. That part is not ready yet, but I hope the release of the FISA IG Report tomorrow will serve as a sounding board to pull those thoughts together.

But since this, the intended third part of the review, was mostly done, I wanted to release it to get it out of the way.

In addition to my other reactions about how this book fails to offer what Snowden has always claimed he wanted to do — offer a defense that he leaked the files in the public interest that could withstand cross-examination — this book harms the version of public interest defense Snowden has always offered. Snowden says that by sharing the NSA files with journalists, he made sure he wasn’t imposing his judgment for society. Given how unpersuasive his explanation for picking (especially) Glenn Greenwald as the journalist to make those choices is, which I addressed in my last post, and given Glenn’s much-mocked OpSec failures, there’s only so far Snowden can take that claim, because it’s always possible adversaries will steal the files or already have from journalists. The Intercept, in particular, went through very rigorous efforts to keep those files secure, but it took them some time to implement and that’s just one set of the files that are out there.

Still, it is a claim that has a great deal of merit. It distinguishes Snowden from WikiLeaks. It mitigates a lot of concerns about the vast quantity of documents he took (or the degree to which they may relate to core national security concerns). I’m a journalist who once lost a battle to release Snowden documents that showed a troubling use of NSA authorities and who a second time chose not to rely on a Snowden document because its demonstrative value did not overcome the security damage releasing it might do. My experience working directly with the Snowden files is really quite limited and rather comical in its frustrations, but I will attest that there was a rigorous process put in place to protect the files and assess whether or not to publish them.

So I’m utterly biased about the value that journalists’ judgment might have served here. But if it ever comes to it, I will happily explain at length how Snowden’s choice to leak to journalists really does distinguish his actions.

Having made that argument, though, Snowden then violates precisely that principle by writing this book.

There hasn’t been a lot of discussion about the disclosures Snowden makes in this book. They pale in comparison to what got disclosed with his NSA files. Nevertheless, I’m certain that Snowden revealed things that have forced CIA to mitigate risks if they hadn’t already done so before the book came out. In particular, Snowden describes the infrastructure of four different IC facilities, mostly CIA ones, in a way that would be useful for adversaries. Sure, our most skilled adversaries likely already knew what he disclosed in the book, but this book makes those details (if they haven’t already been mitigated) accessible to a wider range of adversaries.

More curious still is what Snowden makes a big show of not disclosing. In the book, Snowden describes how he took the files. While he describes sneaking the NSA’s files out on SD cards, he pointedly doesn’t explain how he transferred the files onto those SD cards.

I’m going to refrain from publishing how exactly I went about my own writing—my own copying and encryption—so that the NSA will still be standing tomorrow.

If Snowden really is withholding this detail out of some belief that sharing it would bring the NSA down tomorrow, he effectively just put a target on his back, walking as that back is around Moscow, to be coerced to answer precisely this question. And if Snowden really believes this detail is that damaging to the NSA, his assurances that he destroyed his encryption key to the files before he left Hong Kong and so could not be coerced, once he arrived in Russia, to share damaging information on the US falls flat. By his own estimation, Snowden did not destroy some of the most valuable knowledge he had that might be of interest, information he claims could bring the NSA down tomorrow.

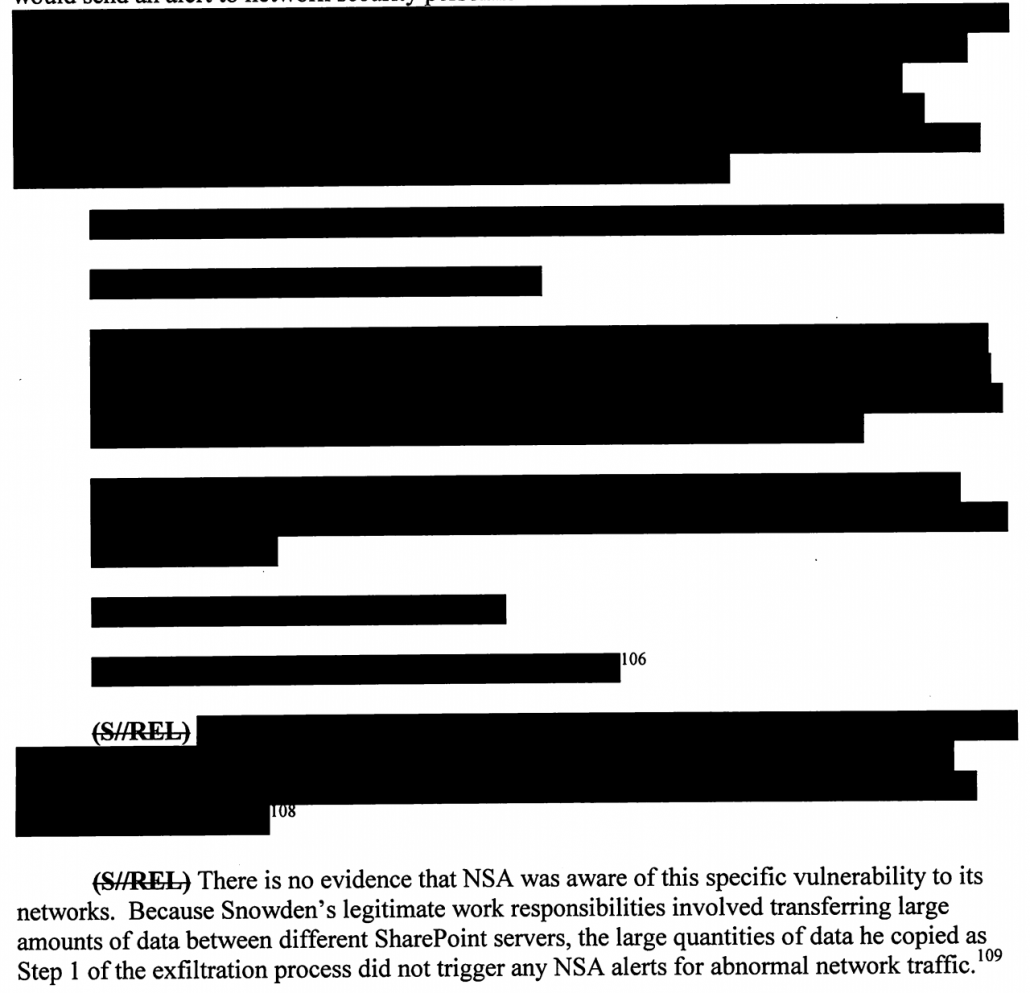

I actually doubt that’s why he’s withholding that detail. After all, the HPSCI Report on Snowden has a three page section that describes this process, including this entirely redacted passage (PDF 18) describing a particular vulnerability he used to make copies of the files, one the unredacted part of the HPSCI report suggests may have been unknown to NSA when Snowden exploited it.

Assuming the NSA, focusing all its forensic powers on understanding what had been, to that point, the agency’s worst breach ever, managed to correctly assess the vulnerability Snowden used by October 29, 2014, the date the NSA wrote a report describing “Methods Used by Edward Snowden To Remove Documents from NSA Networks,” then the NSA has presumably already fixed the vulnerability.

I honestly don’t know why, then, Snowden kept that detail secret. It’s possible it’s something banal, an effort to avoid sharing the critical forensic detail that would be used to prosecute him if he ever were to stand trial (though it’s not like there’s any doubt he took the documents). I can think of other possible reasons, but why he withheld this detail is a big question about the choices he made about what to disclose and what not to disclose in this book.

But that’s the challenge for Snowden, after investing much of a public interest defense in using journalists as intermediaries, now making choices personally about what to disclose and what to withhold. It accords Snowden a different kind of responsibility for the choices he makes in this book. And it’s not clear that, having assumed that role, Snowden met his own standards.

Reading this post made me think of all the other books from newsworthy figures about their own stories, and the choices they make in crafting their narratives. For instance:

+ The Trump Administration staffer, who published “A Warning” anonymously – a tradeoff between personal safety from retaliation (real or imagined) on the one hand and on the other hand declining to give his/her name so that the material’s worth can be more accurately assessed.

+ John Bolton, who signed a book deal to tell the great stories he has around the meetings and debates at the heart of the impeachment inquiry, even as he declines to share those very same stories with Congress unless he gets a court to give him approval.

+ Joe Klein’s anonymously published roman-a-clef “Primary Colors”

You can add a ton more books to this list, going back generations, but I’ll leave it to others to expand the list if you wish.

On top of these, however, are the books written by those who practice “access journalism,” such as Bob Woodward. For many of these folks, they must decide daily how to answer a troubling question: “What goes into today’s paper/webpost/tv show, and what do I hold back for the book?” For the subjects of these books, they weigh the question “How much does giving this person access to my story allow me to get it out in public and at the same time shape it the way I want?”

I raise all this to say Snowden doesn’t have a lot of good models for writing his book. He does understand, though, that this is a kind of storytelling embraced by the culture, despite its pitfalls, flaws, and dangers. Kudos to you, Marcy, for laying out some of those pitfalls, flaws, and dangers here.

True. But that’s one reason why the study of narrative is useful training (as I’m QUITE sure you appreciate). Few people understand how telling narrative gaps can be.

Absolutely. When someone says “Let me tell you about A, B, C, and E” it makes me really curious about D.

For instance, many churches have a wall with photos of former pastors and their years of service, and I’m always curious when there are gaps in the timeline. If I’m really curious and start asking the right people the right questions, it almost always turns out to be important. Someone will tell me “Yes, there was another pastor between C and E, . . .” and the rest of the sentence is the meat of the often ugly story: “. . . who scandalously had an affair with the organist . . .” or “who burned down the parsonage by smoking in bed after a long night of drinking” or “who got thrown out of the ministry for reasons we were never told about but suspect it had to do with young girls.”

Narrative gaps matter.

Beyond the gaps authors create, it’s important to notes the desire/demand to impose narrative gaps on storytellers by others. Think of an ugly divorce, where one party threatens to expose some very ugly behavior, and the other party offers up a threat to tell some ugly stories of their own.

Then there are NDAs.Trump is known for his love of NDAs, so as to seal the mouths of former employees and others with narratives Trump would rather not have aired.

Or consider Mayor Pete’s NDA with McKinsey, which is giving him headaches as well. Even putting the best construction on things, imagine that Mayor Pete was the best consultant ever. With that NDA, Pete can only point to those years and say “I was a great consultant, but I can’t tell you what I did, who I did it for, or what the result was that made my work so great.” Kind of hard to ride a gap in your resume all the way to the White House.

An NDA is like an anti-patent. Yes, you’ve got a story to tell, but you can’t tell it without someone else’s permission. Signing an NDA is giving that part of your story away to someone whose motives may or may not align with yours.

Excellent point.

The most telling narrative gap I’ve ever heard about in history is when FDR made a speech asking that Hitler pledge not to attack a long list of countries. Hitler replied with a speech of his own dripping with sarcasm and denying that he would attack each and every one. Unnoticed by most at the time, he denied each and every one _except for Poland_!

Yes! I feel like you and josh Marshall were two of the few I can remember who, shortly after the Outlaw Billy Barr gave his highly misleading presser (the first one), warned he just might not be a reliable narrator. Which many journalists, headline writers, and even attorneys, missed.

“+ John Bolton, who signed a book deal to tell the great stories he has around the meetings and debates at the heart of the impeachment inquiry, even as he declines to share those very same stories with Congress unless he gets a court to give him approval.”

The position Bolton has taken regarding the points you note here is intriguing to say the least, because it creates a fact pattern that is quite difficult to put into a coherent logical position.

The best I could come up with is that Bolton is a coward who wants to do the right thing. This would explain how he was OK telling a subordinate, “Go talk to the lawyers” (because he had no skin in that game). It also explains how he is handling Congress – basically telling them that he won’t appear without a subpoena (as though the law has somehow changed) because, I suspect, he fears Trump’s wrath.

The fact that Bolton is active with a PAC in support of Republicans tells you clearly that he thinks his role on the national or maybe even international stage is not done yet. But he’s a coward who doesn’t want to incur Trump’s wrath. So if he is legally compelled to testify, then he can defend doing so. On the other hand, if he simply rolls over now so that Congress can tickle his tummy, Trump will undoubtedly attack him and encourage the Trump faithful to spurn Bolton’s PAC.

There’s no doubt in my mind that Bolton thinks he’s being politically astute and playing the long game. There’s no doubt that he wants to avoid the line of fire.

Likewise, there’s no doubt that he’s an utter coward, unable to “do the right thing” even when that opportunity is staring him in the face.

That he won’t appear without a *court order*. Sorry. Pretty sure that he already has received a subpoena.

Um, no. Bolton was never officially subpoenaed, and the one for his aide Kupperman, was withdrawn.

Why do you think I keep laughing at the fecklessness of the House Democrats??

“Given how unpersuasive his explanation for picking (especially) Glenn Greenwald as the journalist to make those choices is, which I addressed in my last post, and given Glenn’s much-mocked OpSec failures, there’s only so far Snowden can take that claim, because it’s always possible adversaries will steal the files or already have from journalists.”

Whilst I agree with you at a general level, I don’t think it was so much Greenwald’s OpSec incompetence that really marks out Snowden’s leaks, but the fact that Snowden is, even today, stuck in Russia, with nowhere to go.

The reason he is there is because Greenwald and MacAskill had such out-sized egos that both of them were more concerned by the other beating them to print than they were with getting their source to safety. That’s the true outrage.

For all his pious talk about wanting to tell the story, Greenwald showed his true colors with his actions, by behaving irresponsibly toward a source who could have easily been at risk of life-long imprisonment or worse had the US authorities caught up with him.

I’m sure he’d rather come back to the US than stay in Russia, but it’s not like he’s in some gulag in Siberia. By all accounts, he’s living in Moscow, which isn’t NYC, but it’s still a city with a lot of culture to it with a lot of things to see and do, and it’s relatively easy to blend in at this time of year, when everyone is bundled up. I don’t see him getting ex-filed from Russia, either. So yes, he’s in exile, but he’d be in a hell of a lot worse shape if he hadn’t gotten to Russia.

This, @sproggit—and Greenwald has showed his true colors in many ways since. There’s only one other American individual I can think of who so regularly disparages America, particularly American reporters, citizens and lawyers uncovering the crimes of Putin, while refusing to breath even a hint of criticism of the Poisoner. That other American being of course, the coarse, rotund and treacherous orange unindicted co-conspirator Individual-1, as he’s referred to in court filings by the SDNY.

In other words, GG has got some ‘splaining to do.

Yeppers!! Kompromat is a mother! Ah, welcome to the postmodern age of corruption.

My understanding is that Snowden has reconciled himself to the reality that if he returned to the US for arrest and trial, he would most likely spend most (if not all) of the rest of his life in prison. In this context, the current treatment of Julian Assange is prophetic and germane. He has built a new life in exile and continues to contribute to the cause of exposing government surveillance excesses and the extinction of personal privacy. IOW, he can still lead a relatively productive and useful life as opposed to indefinite isolation in 8 x 10 foot cell. I think he wrote Permanent Record simply to tell his side of the story for posterity and not as an aid to a potential future legal defense. He will be remembered for the sacrifice he has already made and not so much for having beat the wrap, if that should come to pass.

Lol. Assange spent the better part of a decade holed up in a broom closet in the Ecuadoran embassy in London and is now in a UK prison.