The NYT wrote an 1800-word, 5-byline post claiming Elon Musk’s departure from DOGE reflected tensions over Trump’s Big Ugly Tax Bill without mentioning one additional — possibly far more important — factor that may have influenced his announced departure.

This may be an attempt to preserve the damage Elon did to government, up to and including the data consolidation that DOGE carried out.

Even NYT’s claimed basis for Elon’s departure is unpersuasive.

On Tuesday, CBS posted a clip from an interview that will air Sunday, in which Musk complains that the Big Ugly Tax Bill raises the deficit.

Elon Musk says he is “disappointed” by the price tag of the domestic policy bill passed by Republicans in the House last week and heavily backed by President Trump. The billionaire who recently stepped back from running the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, made the remark during an exclusive broadcast interview with “CBS Sunday Morning.”

“I was disappointed to see the massive spending bill, frankly, which increases the budget deficit, not just decreases it, and undermines the work that the DOGE team is doing,” Musk said.

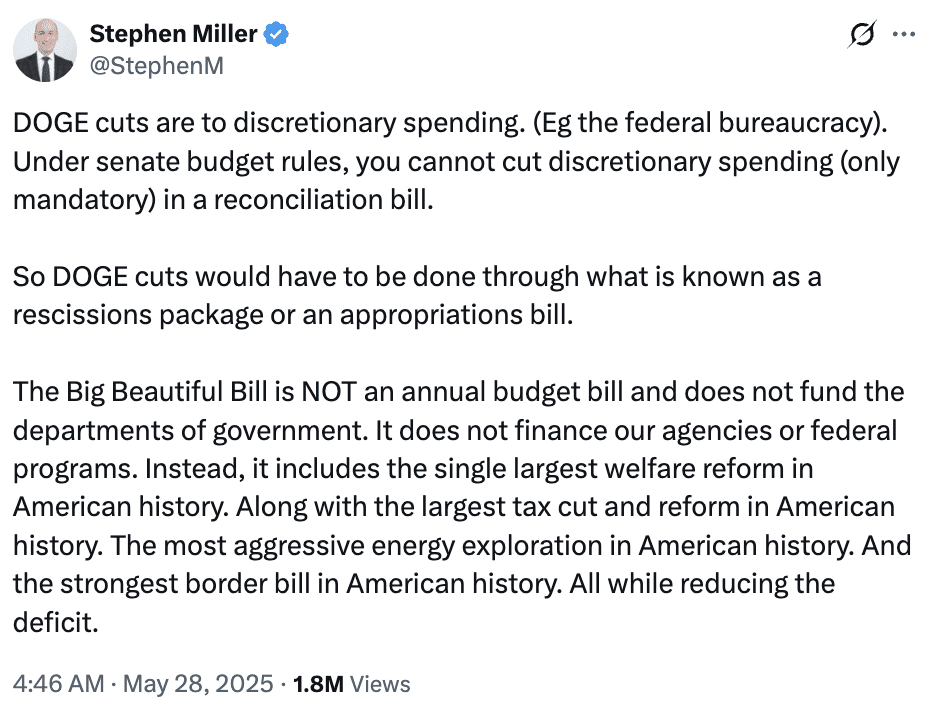

NYT claims that this tweet was a response to Elon. (These screencaps are ET+6.)

That led, NYT claims, to Elon’s announced departure from DOGE.

As it is, there are problems with this narrative. The non-inclusion of DOGE was not Elon’s prior complaint about the Big Ugly; the exacerbation of the budget deficit was. There were plenty of people, in Congress and outside, who were complaining that the Big Ugly didn’t codify DOGE cuts or did fund USAID, complaints more directly relevant to Stephen Miller’s comment. And Miller has been lying about the bill already.

Maybe the NYT’s portrayed drama is correct.

Or maybe this is yet more theater about Elon’s relationship with the Trump Administration.

There was an important DOGE-related development in recent days that may be impacted by Elon’s claimed imminent departure, one not mentioned in NYT’s long story.

After John Roberts, on Sunday, stayed a Christopher Cooper order regarding a FOIA that CREW served on DOGE, on Tuesday, Tanya Chutkan denied DOJ’s effort to dismiss an Appointments Clause lawsuit by blue states — led by New Mexico — against DOGE. [docket]

The DC Circuit (Henderson, Millett, and Walker) had earlier stayed a discovery order from Chutkan pending her decision on the motion to dismiss, holding that she should only grant discovery if the lawsuit will continue. If Chutkan’s decision stands, the government may have to provide the discovery on DOGE that John Roberts halted (in a different, FOIA, context).

Chutkan summarized a list of things the states allege Musk did that would require Senate confirmation.

States claim that DOGE, with Musk at the helm, “has inserted itself into at least 17 federal agencies” and exercises “significant authority” across the Executive Branch. Id. ¶¶ 70, 200. They identify the following categories of allegedly unauthorized actions by DOGE and Musk:

- Controlling Expenditures and Disbursements of Public Funds: States allege that DOGE obtained “full access” to payment systems at multiple agencies and used that access to halt payments. Id. ¶¶ 78–79, 85, 127–30. For instance, after the acting-Secretary at U.S. Department of Treasury refused to “halt” payments, DOGE personnel threatened the acting Secretary with “legal risk [] if he did not comply with DOGE.” Id. ¶ 84. Then, on February 2, DOGE obtained “full access” to Treasury’s Bureau of the Fiscal Services payment systems, which disburses funds for social security benefits, veteran’s benefits, childcare tax credits, Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements, federal employee wages, federal tax refunds, and facilitates state recovery of delinquent state income taxes. Id. ¶¶ 78–79, 85. That day, Musk posted on X that “[t]he @DOGE team is rapidly shutting down these illegal payments,” in response to a post by a non-profit organization receiving funds pursuant to government contracts. Id. ¶ 86.

- Terminating Federal Contracts and Exercising Control over Federal Property: States allege that Musk and DOGE asserted responsibility for terminating federal contracts across the Executive Branch. Id. ¶ 203–04. DOGE reported the cancellation of “104 contracts related to diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility (DEIA) at more than a dozen federal agencies” on January 31, id. ¶ 205; of “thirty-six contracts across six agencies” on February 3, id. ¶ 206; of “twelve contracts in the GSA and the Department of Education” on February 4, id. ¶ 207; and “cuts of $250 million through the termination of 199 contracts” on February 7, id. ¶ 208. States also allege that DOGE and Musk exercise control over federal property by demanding access to secure facilities and threatening intervention by U.S. Marshals when agency officials refuse, id. ¶¶ 94–95; by “push[ing]” high-ranking officials out of their offices at agency headquarters, id. ¶¶ 164–66, by terminating leases for federal property, id. ¶ 206, and by announcing plans to “liquidate as much as half of the federal government’s nonmilitary real estate holdings,” id. ¶ 160.

- Binding the Government to Future Financial Commitments without Congressional Authorization: States point to the Fork in the Road Email, which offered federal employees pay and benefits through September 2025 if they resigned by February 6, as entering into binding financial commitments. Id. ¶¶ 116–20, 212.

- Eliminating Agency Regulations and Entire Agencies and Departments: States allege that DOGE personnel took steps to dismantle USAID and CFPB. On February 3, DOGE personnel allegedly “handed” USAID’s acting leadership “a list of 58 people, almost all senior career officials, to put on administrative leave.” Id. ¶ 102. The next day, USAID placed “nearly its entire workforce on administrative leave.” Id. ¶ 103. When “USAID contract officers emailed agency higher-ups” for authorization to cancel programs, DOGE personnel responded directly. Id. ¶ 101. Musk posted on X “CFBP RIP” on the same day that Musk’s aides “set up shop . . . at CFPB’s headquarters” and CFPB’s website was taken down. Id. ¶¶ 146–47. Three days later, CFPB’s acting Director Russell Vought told all employees to “[s]tand down from performing any work task” and “not come into the office.” Id. ¶ 148.

- Directing Action by Agencies: States allege that Musk and DOGE obtain compliance from agency officials and employees by threatening action by U.S. Marshals, legal risks, or termination. Id. ¶ 84 (threatening acting-Treasury Secretary with “legal risk”); id. ¶ 95 (threatening USAID personnel blocking access to facility with action by U.S. Marshals); id. ¶¶ 176–178 (DOL employees told to comply or “face termination”). States claim that if agency officials object or raise concerns, Musk and DOGE ignore or override the agency and place on administrative leave or otherwise remove non-compliant individuals. Id. ¶¶ 84– 85 (acting-Treasury Secretary “placed on administrative leave” after refusing to halt payments); id. ¶ 110 (DOGE “gained full and unfettered access to OPM systems over the existing CIO’s objection”); id. ¶¶ 137–38 (DOGE representative was “installed” as the Department of Energy’s (“DOE”) “chief information officer” after DOE’s general counsel’s office and chief information office opposed DOGE’s access to DOE’s IT system); id. ¶ 166 (DOGE personnel “pushed” the “highest-ranking officials” at the Department of Education (“ED”) “out of their own offices”).

- Acting as a Principal Officer Unsupervised by Heads of Departments: States allege that Musk acts and directs DOGE’s conduct without supervision by agency heads. For instance, States allege that Musk and his team sent the Fork in the Road Email “via a custom-built email system . . . without consultation with other advisers to the President or OMB officials,” id. ¶ 120; that DOGE personnel at agencies do not “interact at all with anyone who is not part of their team,” id. ¶ 165; and that Musk “reports only to President Trump,” id. ¶ 71.

- Obtaining Unauthorized Access to Secure Databases and Sensitive Information: States allege that Musk and DOGE personnel obtained access to secure databases and systems at Treasury, id. ¶ 85, USAID, id. ¶ 95, OPM, id. ¶ 110, the Department of Health and Human Services, id. ¶ 127, DOE, id. ¶ 137, ED, id. ¶¶ 164, 167, DOL, id. ¶¶ 177–78, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, id. ¶ 190, Federal Emergency Management Agency, id. ¶ 194, and Small Business Association, id. ¶ 198.

These are all the DOGE actions that might be imperiled if this lawsuit succeeds.

Chutkan’s opinion sustaining the lawsuit focused closely on Elon’s role in DOGE.

Elon Musk’s role, authority, and conduct within the federal government is a central issue in this case. Defendants formally classify Musk as a “special Government employee.” Compl. ¶ 25 (citing 18 U.S.C. § 202(a)); see also Decl. of Joshua Fisher ¶¶ 3–4, ECF No. 24-1. Plaintiff States allege that Musk leads DOGE and directs the actions of DOGE personnel. Compl. ¶¶ 51, 59. Specifically, they claim that the “statements and actions of President Trump, other White House officials, and Mr. Musk himself indicate that Mr. Musk has been directing the work of DOGE personnel since at least January 21, 2025.” Id. They allege that, in this role, Musk “exercise[es] virtually unchecked power across the entire Executive Branch, making decisions about expenditures, contracts, government property, regulations, and the very existence of federal agencies.” Id. ¶ 67.

And given the precedents, it necessarily focused on whether Musk’s position at the head of DOGE is “continuing.”

That does not end the court’s inquiry. Having concluded that special government employees are not automatically exempt from the Appointments Clause, the court must assess whether Musk’s particular position is “sufficiently ‘continuing’ to constitute an office.” United States v. Donziger, 38 F. 4th 290, 296 (2d Cir. 2022), cert denied, 142 S.Ct. 868 (2023). In doing so, the court takes a holistic approach, focusing on a position’s “tenure, duration, emolument, and duties,” and whether the duties are “continuing and permanent, not occasional or temporary.” United States v. Germaine, 99 U.S. 508, 511–12 (1878); The Test for Determining “Officer” Status Under the Appointments Clause, 49 Op. O.L.C. __, slip op. at 3 (Jan. 16, 2025) (“[T]he Supreme Court’s approach to assessing the ‘continuing’ nature of a position has been a holistic one that considers both how long a position lasts as well as other attributes of the position that bear on continuity.” (citations omitted)). Positions that do not qualify are “transient or fleeting,” “personal to a particular individual,” and assigned merely “incidental” duties. Donziger, 38 F.4th at 296–97 (citation omitted).

[snip]

States allege that Musk is DOGE’s leader. Compl. ¶¶ 59–60, 224. The court finds that States have sufficiently pleaded that this position qualifies as “continuing and permanent, not occasional or temporary,” Germaine, 99 U.S. at 511–12. The subsidiary DOGE Service Temporary Organization has a termination date of July 4, 2026, but there is no termination date for the overarching DOGE entity or its leader, suggesting permanence.

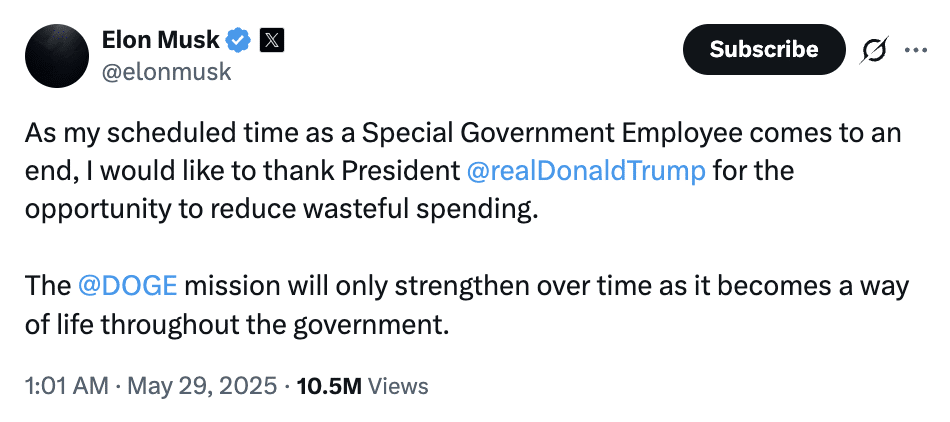

So on Tuesday, Judge Chutkan ruled that Elon’s continuing role in DOGE made this lawsuit viable. On Wednesday, Elon announced he would not be continuing at DOGE.

The government has already filed with the DC Circuit asking to offer additional briefing on its challenge to Judge Chutkan’s orders.

Way back in February I pointed out the viability of an Appointments Clause challenge before SCOTUS explained the obvious efforts to retcon Elon’s role.

In a response and declaration, the government blew off the first question [ordering details about DOGE firing plans], but on the second, denied that Musk has the power of DOGE. He’s just a senior Trump advisor, one solidly within the White House Office, and so firewalled from the work of DOGE, yet still protected from any kind of nasty disclosure requirements.

But as the attached declaration of Joshua Fisher explains, Elon Musk “has no actual or formal authority to make government decisions himself”—including personnel decisions at individual agencies. Decl. ¶ 5. He is an employee of the White House Office (not USDS or the U.S. DOGE Service Temporary Organization); and he only has the ability to advise the President, or communicate the President’s directives, like other senior White House officials. Id. ¶¶ 3, 5. Moreover, Defendants are not aware of any source of legal authority granting USDS or the U.S. DOGE Service Temporary Organization the power to order personnel actions at any of the agencies listed above. Neither of the President’s Executive Orders regarding “DOGE” contemplate—much less furnish—such authority. See “Establishing and Implementing the President’s Department of Government Efficiency,” Exec. Order No. 14,158 (Jan. 20, 205); “Implementing the President’s ‘Department of Government Efficiency’ Workforce Optimization Initiative,” Exec. Order 14,210 (Feb. 11, 2025).

The statement is quite obviously an attempt to retcon the structure of DOGE [sic], one that Ryan Goodman has already found several pieces of evidence to debunk.

But it is a testament that the suit in question — by a bunch of Democratic Attorneys General, led by New Mexico [docket] — might meet significant success without the retconning of Elon’s role.

[snip]

The retconning of his role is all the more obvious when you understand that the right wing judges on SCOTUS feel very strongly about the Appointments Clause. And Trump is on the record relying on it, most spectacularly in convincing Aileen Cannon that Jack Smith had to be confirmed by the Senate before he could indict Trump.

In practice, Trump is saying Elon can dismantle entire agencies without Senate confirmation, but Jack Smith couldn’t prosecute him as a private citizen without it.

Or he was. Now he’s arguing that all this is happening without Elon’s personal direction.

And here we are again, two months later, and the apparent retconning has not stopped.

This ploy has already worked once. After Judge Theodore Chuang ruled that a USAID-focused Appointments Clause lawsuit was likely to succeed, the Fourth Circuit overruled him. Then DOJ installed DOGE staffer Jeremy Lewin as USAID Administrator, and actions which, back in February, were done by DOGE, now appear to be agency actions. On Tuesday, Chuang denied plaintiffs in that suit discovery.

These lawsuits are different. DOGE did a number of things at other agencies — most notably the data consolidation — that weren’t a central feature of shutting down USAID. Elon’s role at some other agencies was even more clearcut than Judge Chuang found at USAID.

But even if the states can show that Elon exercised the authority to override agency heads, as he reportedly did in several instances, the government is likely to point to Elon’s departure as proof that his appointment was always temporary, and therefore did not require Senate confirmation.

DOJ has been retconning what happened with DOGE for four months now. There’s no reason to believe the drama at this point.