There have been a slew of profiles or useful commentary on Stephen Miller this year:

- January 16, 2025: NYT describes how he built power (with a focus on his cultivation of Mark Zuckerberg)

- March 10, 2025: David Klion reviews Jean Guerrero’s 2021 biography, Hatemonger, with an eye on understanding Stephen Miller’s Jewish background

- May 9, 2025: NYT considers Stephen Miller’s (thus far, at least, abandoned) attack on habeas corpus

- May 30, 2025: NYT traces Stephen Miller’s Salvadoran operation to his obsession with the Alien Enemies Act

- June 14, 2025: Guardian considers how the invasion of Los Angeles might be viewed as revenge

- June 20, 2025: WSJ describes how thoroughly Miller guides Trump’s White House

- June 25, 2025: ProPublica talks about Miller’s attempt to centralize investigations into organized crime

- July 7, 2025: Jason Zengerle compares Miller’s failures in the first term with his successes in this one, while considering what might halt that success

- September 15, 2025: Bulwark discusses Miller’s plan to exploit Charlie Kirk’s killing

- October 9, 2025: John Harwood argues Miller is uniquely fascist

- November 28, 2025: Andrew Egger and Catherine Rampell discuss his latest devious plans to strip work permits

- December 15, 2025: Greg Sargent reviews his xenophobic plans

- December 18, 2025: WaPo describes how he started with a plan to attack Mexico but instead murderboated Venezuelans

There are more I’m still searching for; I’ll add them when I find links.

There has also been great reporting on what happened to the Venezuelan men sent to CECOT, including multiple ProPublica articles, this Frontline documentary, the 60 Minutes episode Bari Weiss killed, and this Tim Miller interview.

There has even been reporting on the weird relations the Trump administration has pursued with Venezuela, first sending Ric Grenell to negotiate and then moving an entire fleet to murderboat Venezuela into submission. The Atlantic’s version of the latter describes that, “Stephen Miller views the air strikes as an opportunity to paint immigrants as a dangerous menace” — murder as propaganda tactic.

There were reports when the Venezuelan men were sent home in July as part of a prisoner swap for ten Americans.

But in spite of the sustained focus on Stephen Miller, the CECOT operation, and Trump’s turn to Venezuela, I’m aware of no story that explains how — much less why — the Administration shifted from staging stunts in the Oval Office with Nayib Bukele and claiming Trump is helpless to do anything about the men he sent to torture, to instead sending them all to Venezuela as part of a purported prisoner swap.

To be sure, there’s a sense of what could explain the move.

Maybe Trump’s team just used the Salvadoran concentration camp to pressure Nicolás Maduro to accept its own deportees. Maybe the sustained focus on the prison — to say nothing of coverage of witnesses who tied Bukele to MS-13 — created problems for the Salvadoran strongman. Maybe the attention on Kilmar Abrego and his release raised pressure to release the others. Maybe one or two of the Americans stuck in Venezuela were that valuable to the Administration to make the swap worthwhile (aside from the ex-Marine triple murderer freed as a result of the swap, there has been far less focus on the Americans who were released than on the Venezuelans the US sent away). Maybe after John Sauer was confirmed in early April and he reviewed the paperwork — to say nothing of SCOTUS’ intervention on Easter weekend to prevent another AEA deportation operation — Miller was informed that his AEA deportations would be unsustainable even with a court packed to support Trump.

All of those are possible. None have been substantiated in reliable reporting.

And as a result, we don’t know what it looks like when one of Stephen Miller’s most extreme experiments with fascism fails. Aside from the public reporting on tensions between Grenell and Marco Rubio, there’s no discussion of whether Stephen Miller also lost out in a political dispute and if so how, or whether he was just placated by the opportunity to serially murderboat Latinos as a consolation prize.

Even the Administration is hiding how this went down. When the government told its story, as part of Judge Boasberg’s since re-halted contempt inquiry, of how it blew off Boasberg’s order to return the flights to El Salvador back in March, they did not include Stephen Miller in that story.

1. At approximately 6:45 PM on March 15, 2025, the Court orally directed counsel for the Government to inform his clients of the Court’s oral directives at the hearing, including statements directing that any removed class members “need to be returned to the United States.” By that point, two flights carrying individuals designated under the Alien Enemies Act (AEA) had already departed from the United States and were outside United States territory and airspace.

2. At approximately 7:25 PM, the Court memorialized its temporary restraining order in a written order, as the Court had indicated at the hearing it would do. The written order enjoined Defendants “from removing” class members pursuant to the AEA. The written order, unlike the oral directives, said nothing about returning class members who had already been removed.

3. Deputy Assistant Attorney General Drew Ensign promptly conveyed both this Court’s oral directives and its written order to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), through its Office of General Counsel, and to the leadership of the Department of Justice (DOJ).

4. Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche and Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General Emil Bove provided DHS with legal advice regarding the Court’s order as to flights that had left the United States before the order issued, through DHS Acting General Counsel Joseph Mazzara. Mr. Mazzara then conveyed that legal advice, as well as his own legal advice, to Secretary of Homeland Security, Kristi Noem. See 6 U.S.C. § 113(a)(1)(J). After receiving that legal advice, Secretary Noem directed that the AEA detainees who had been removed from the United States before the Court’s order could be transferred to the custody of El Salvador. As explained below, that decision was lawful and was consistent with a reasonable interpretation of the Court’s order.

5. Although the substance of the legal advice given to DHS and Secretary Noem is privileged, the Government has repeatedly explained in its briefs—both in this Court and on appeal—why its actions did not violate the Court’s order, much less constitute contempt. Specifically, the Court’s written order did not purport to require the return of detainees who had already been removed, and the earlier oral directive was not a binding injunction, especially after the written order.

It all happened without any involvement from Stephen Miller, if you can believe that.

There’s certainly reason to believe that if Erez Reuveni told his side of the story (testimony that was also thwarted by the DC Circuit’s renewed stay of the contempt proceeding), these redacted bits might disclose the role of the White House in the decision.

But in spite of all the profiles describing — credibly, to be sure — that Miller is really the one running most policy out of the White House, the government has gone to some lengths to avoid confirming that in legal contexts, perhaps for all the legal problems that would arise if Trump had to explain how he’s not the one who signed the Alien Enemies Act.

Vanity Fair’s profile of Susie Wiles described — and seemingly quoted her as agreeing — the deportation effort as a failure.

In mid-March, after Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents (ICE) shackled and herded 238 immigrants onto transport planes and flew them to a notoriously brutal Salvadoran prison. According to Trump, the men were members of Tren de Aragua, a violent Venezuelan gang, but the evidence was sketchy (often based on tattoos alone). Most had committed no serious crimes; one, Kilmar Abrego Garcia, was deported by mistake, the Trump administration admitted.

“I will concede that we’ve got to look harder at our process for deportation,” Wiles told me at the time.

When we spoke again in April, in cities across the country, masked ICE agents were snatching people off the street, throwing them in vans, and zip-tying and frog-marching them into makeshift deportation camps. Many were US citizens or entitled to be here. (ProPublica documented 170 cases in the first nine months of 2025 of US citizens being caught up in ICE’s dragnet.)

“If somebody is a known gang member who has a criminal past, and you’re sure, and you can demonstrate it, it’s probably fine to send them to El Salvador or whatever,” Wiles told me. “But if there is a question, I think our process has to lean toward a double-check.” But as the usa.gov site itself notes, “In some cases, a noncitizen is subject to expedited removal without being able to attend a hearing in immigration court.”

But there’s no hint that the Administration as a whole shares the opinion attributed to Wiles, and Miller’s other abusive deportations have continued with no pause.

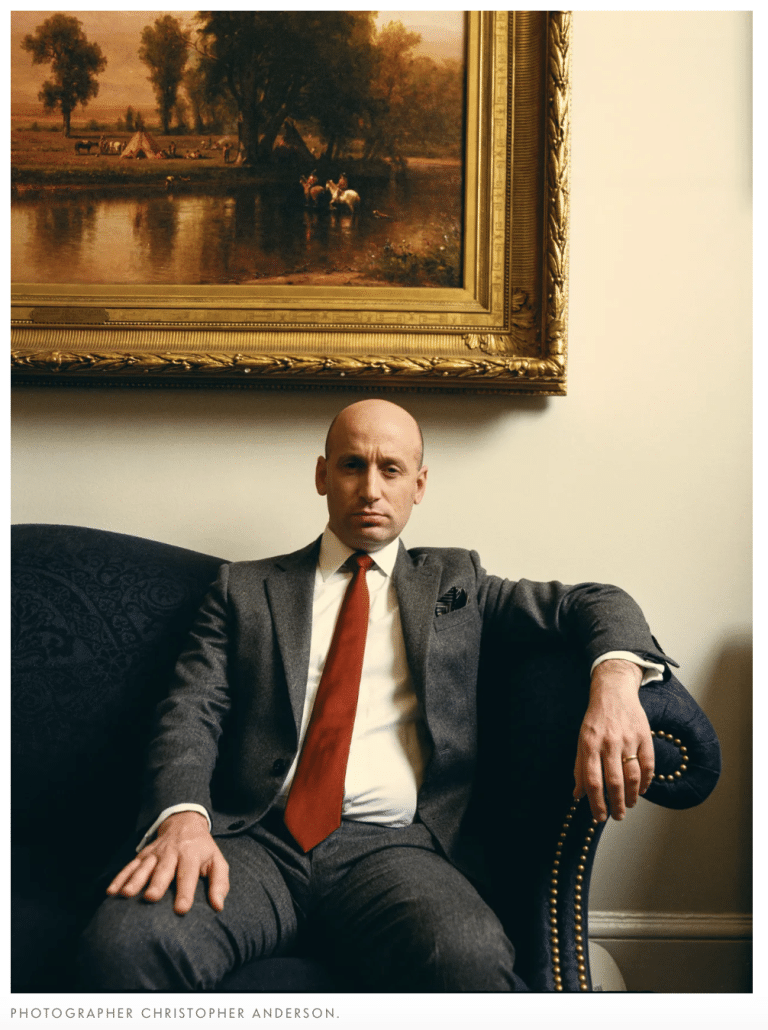

Photographer Christopher Anderson’s two descriptions of taking that photograph of Miller, which Vanity Fair sandwiched right in the middle of the El Salvador discussion, may be one of the few pieces of journalism describing Miller’s vulnerabilities.

What is the encounter you remember most?

For me the most interesting encounter for the day was with Stephen Miller. I find him to be a really interesting character on many levels, both at this moment in time and just what he represents and how he carries himself. He’s not someone who’s been photographed a lot in this way. So he was clearly a little bit nervous about sitting for a portrait, and he asked a lot of questions. “Why are you doing this? Why are you shooting film as opposed to shooting digital? Why do you know what that thing does? And how does it look? How am I? How do I look sitting here? Does it look like I’m slouching?” And at one point, I said to him, “you know, the people may say a lot of things about you, but slouching is not one of the things they will accuse you of.” And at the end of the session he comes up to me to say goodbye, and he says, “You know, you have a lot of power in the discretion you use to be kind to people,” meaning kind to people in my pictures. And I looked at him, and I said, “Yeah, you know, you do too.” It was interesting to me, his reaction. But just being in that place is in itself a fascinating experience, to be kind of within the halls of that kind of power, but yet to see it that it is a little bit [like] the Wizard of Oz behind the curtain. The place is small and shabby and you see paint marks on the wall, the wiring is done in a shabby way, and the desks can be messy, and it’s—I guess it’s a little bit like looking at middle management at a lot of companies.

[snip]

Is there anything the readers haven’t yet noticed in your pictures?

There’s the one Easter egg that I hoped people might see, and maybe they are starting to see a little bit, is that I had Stephen Miller sit underneath one of the oil paintings in the Roosevelt Room that is a beautiful depiction of Native Americans crossing a river on horseback to return to their teepee village home. It was one of those things that—I found it to be kind of interesting and maybe incongruous, that I thought might be picked up on. Go look, go look for it.

But while a bunch of the Miller profiles talk about how powerful he is (most have sources protected by further anonymity describing how much some portion of Republicans in Congress hate him), few to none talk about what a Miller setback in this administration looks like.

I’ve been thinking about that as part of my year-end inventory of what we’ve learned this year.

To halt Trump’s worst abuses, Stephen Miller must be made toxic — which is not hard to do, at least not if people are granted anonymity. The costs his bigotry causes — the dollar signs, the trade-offs the monomaniacal implementing of his bigotry entails, the human cost of prioritizing bigotry over saving children from sexual assault — must be made visible.

But it would also become necessary to understand what confluence of events could lead Miller to experience a policy setback. Preferably not just one setback, but all of them, a collapse of his near-monopoly on the President’s ear and therefore on policy.

Contrary to his well-curated press, Stephen Miller is not omnipotent. His slovenly execution makes him even more vulnerable. He hates when his physical tics are visible; he probably also hates that his paunch appears in that same photo.

His long-planned bid to use the Alien Enemies Act to deport men based off soccer tattoos to be indefinitely tortured failed.

And we don’t know how or why it failed.

Update: This NYT story fills in some of the circumstances surrounding these events — describing a team that makes shit up on the fly, excludes experts, and then changes their mind months later. At its core is a flipflop (or perhaps cynical manipulation of Cuban-American legislators) on Chevron’s license to export oil from Venezuela.

It began when Cuban American lawmakers pressed Mr. Trump early this year to end Chevron’s Biden-era confidential license. After Mr. Trump and Mr. Rubio announced in late February that they would do so, Mr. Maduro stopped accepting deportation flights of Venezuelans. Mr. Maduro had agreed to them on Jan. 31 with Richard Grenell, a special envoy for Mr. Trump.

Chevron’s chief executive, Mike Wirth, lobbied the administration for a license extension, speaking to Mr. Trump several times over the coming months.

The Cuban American lawmakers got wind that the license could be extended, and they threatened to withhold their votes for Mr. Trump’s signature legislation, “the One Big Beautiful Bill.”

At the Oval Office meeting in late May, Mr. Trump told Mr. Rubio and Mr. Miller that he needed to get the bill passed. But he said he had heard about the downsides of ending the license, including that Chinese companies would take over Chevron’s stakes, said an official.

The president demanded options. That was when Mr. Miller offered to help. He had been nurturing his ideas for mass deportations and boat strikes.

Mr. Trump did not renew Chevron’s license when it expired on May 27. His domestic policy bill passed Congress five weeks later.

The president held a series of White House meetings on whether to strike at Venezuela. At one in the early summer that included Mr. Rubio, Mr. Miller and Mr. Grenell, Mr. Rubio argued that Mr. Maduro was a drug kingpin, a characterization that appeared to stick with Mr. Trump, an official said.

In late July, Mr. Trump reversed course on Chevron’s license. He ordered the Treasury Department to issue one with revised terms. That happened around the time Mr. Maduro freed 10 American prisoners in exchange for the more than 250 Venezuelans that the Trump administration had sent to CECOT, the Salvadoran prison. And Mr. Trump had been swayed by Mr. Wirth’s argument that Chevron was a bulwark against China.

But behind the scenes, Mr. Trump set a course for confrontation. On July 25, he signed a secret order telling the Pentagon to take action against drug-trafficking groups, putting in motion the targeting of Venezuelans.