The Awlaki Memo has just been released. This post will be a working thread. Note, page numbers will be off the page numbers of the memo itself (starting at PDF 61).

Pages 1-11: Barron takes 11 pages to lay out both the claims the government made about Anwar al-Awlaki and the request for an opinion. All of that is redacted.

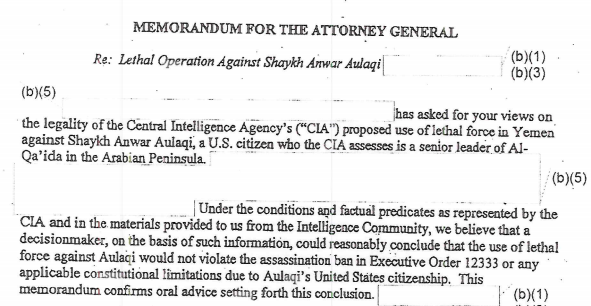

Page 12: This memo is particularly focused on 18 USC 1119, which OLC only treated because Kevin Jon Heller raised it in a blog post. Note that OLC splits its consideration of whether DOD could kill Awlaki (which it probably could) from its consideration whether CIA could (which is far more controversial). The memo seems to have been written so as to authorize both DOD and CIA to carry out the operation, whichever got around to it. Also note the memo assumes the earlier Barron memo that authorizes this secret due process gimmick.

Page 13: OLC’s analysis is closely tied to legislative history, which is fine. Except that DOJ routinely ignores legislative history when it doesn’t serve its purposes.

Page 15: Footnote 12 argues that after invoking public authority jurisdiction the government doesn’t have to say what happened to the law:

There is no need to examine whether the criminal prohibition has been repeated, impliedly or otherwise, by some other statute that might potentially authorize the governmental conduct, including teh authorizing statute that might supply the predicate for the assertion of the public authority justification itself.

Nothing is cited to defend this proposition. It seems like a giant hole in the opinion, though I await the lawyers to tell me whether that’s the case.

Page 15: Note the government has redacted all the other memos listed in Fn14 where it has exempted itself from criminal law.

Page 16: The government only leaves Nardone unredacted in FN15 among laws where Congress has limited Congressional action. That seems … odd.

Page 17: Note that part of FN 20 is redacted. This seems to justify other claims OLC made that something wasn’t illegal.

Page 18: Note the redaction describing the kind of CIA operation here. I’d be curious whether it used Traditional Military Activities or paramilitary, as the distinction is a crucial one but one that often gets ignored.

Page 19: Note how the language on “jettison[ing] public authority justification” as if it existed prior to 1119 for both DOD and CIA.

Page 19: This is likely one reason why Ron Wyden keeps asking for more specifics:

Instead, we emphasize the sufficiency of the facts that have been represented to us here, without determining whether such facts would be necessary to the conclusion we reach.

Page 21: Note that one of the things OLC concludes — rather than restates — in the redacted 11 pages that start the opinion is the AUMF language. It appears by reference in this form.

And, as we have explained, supra at 9, a decision-maker could reasonably conclude that this leader of AQAP forces is part of al-Qaida forces. Alternatively, and as we have further explained, supra at 10 n 5, the AUMF applies with respect to forces “associated with” al-Qaida that are engaged in hostilities against the U.S. or its coalition partners, and a decision-maker could reasonably conclude that the AQAP forces of which al-Aulaqi is a leader are “associated with” Al Qaeda forces for purposes of the AUMF.

Two things about this: by this point (July 2010), the government had already gotten away with this “associated forces” claim in Gitmo habeas filings. But if that’s what they rely on, why not leave it unredacted? (Note, they do cite it on the next page, but not in this discussion.)

Also, note they don’t describe whether they concluded Awlaki was a leader, or whether they just accepted the government’s assertion?

Later on that page it says:

Based upon the facts represented to us, moreover, the target of the contemplated operation has engaged in conduct as part of that organization that brings him within the scope of the AUMF. High-level government officials have concluded, on the basis of al-Aulaqi’s activities in Yemen, that al-Aulaqi is a leader of AQAP whose activities in Yemen pose a “continued and imminent threat” of violence to Untied States persons and interests. Indeed, the facts represented to us indicate that al-Aulaqi has been involved, through his operational and leadership roles within AQAP, in an abortive attack within the United States and continues to plot attacks intended to kill Americans form his base of operations in Yemen.

This is interesting for several reasons. First, it emphasizes reliance on the facts presented. But this is an area where DOJ has lied (they’ve lied to me, for example). It’s an area where Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab’s 3 public confessions conflict. So it is not an area where they should be trusted.

Note, they call the UndieBomb attack an “abortive” attack, which I find an interesting (though in no way erroneous) word choice for unsuccessful.

Also note they claim Awlaki “continues to plot attacks.” Remember they had Jabir al-Fayfi infiltrated into AQAP at this time. But also remember that reports after Fayfi came out pinned the blame for the toner cartridge plots more heavily on other AQAP members.

Page 23: Note how the memo applies the not-on-battlefield justification for detention to not-on-battlefield justification for killing. There seems to be a necessary logical step missing.

Page 23: Also note how sometimes the memo devolves into calling Awlaki “part of the forces of an enemy organization.” Not only does that make me wonder whether the language on “leader” was always what it currently is, but also this seems to mean this killing authority would apply to more junior members of an AUMF group.

Page 23: Included a memo authorizing the killing of someone not wearing a uniform about whom there is conflicting information about membership: “When a person takes up arms or merely dons a uniform as a member of the armed forces, he automatically exposes himself to enemy attack.”

Page 24: The memo describes Yemen as “far from the most active theater of combat between the United States and al-Qaida.”

Page 24: Footnote 30 reiterates that this only applies to the circumstances presented, which is something footnote 1 apparently deals with as well (as all footnotes 1 in OLC memos likely do).

Page 24: OLC is secretly trolling the other branches:

nearly a decade after its enactment, none of the three branches of the United States Government has identified a strict geographical limit on the permissible scope of the authority the AUMF confers on the President with respect to this armed conflict.

That’s absolutely right! Now let’s see if it inspires SASC to get to work on that front. Though as I noted in my working thread on the white paper, its citation to letters from the executive branch to Congress, and its silence on Tom Daschle’s objections, are problematic.

Also note, this memo is not referenced in the white paper (see the equivalent section in paragraph 7).

DOD May 18 Memorandum for OLC, at 2 (explaining that U.S. armed forces have conducted [redacted] AQAP targets in Yemen since December 2009, and that DoD has reported such strikes to the appropriate congressional oversight committees.

I find that mighty interesting as the primary audience for the white paper was Congress, especially given that we know the government doesn’t brief the committees on all the lethal operations they conduct. Did they claim to OLC they have briefed Congress when they hadn’t?

Page 25: Interested in the “where the principal theater of operations is not within the territory of the nation that is a party to the principal theater of operations.” Will have to ask the lawyers wtf that means in context. Also, at the time one could have argued that Saleh was playing both sides.

Page 25: Just remarking, again, that they used Cambodia to justify this, as if that weren’t a warning.

Page 27: I look forward to what the lawyers say about FN 35, but it seems like it should get some of their other terror claims in trouble.

Page 27: Wondering whether the “operation in Yemen” information should have included analysis of Djibouti and Saudi Arabia’s role?

Page 27: Note the “continuously planning” argument is in the redacted section.

Page 29: As you read the language on avoiding civilian casualties, remember that there are reasons to believe Awlaki’s son was taken out intentionally.

Page 30: Note the big redaction after the section on Awlaki “offering to surrender.” This must be particularly interesting since the footnote introduces the notion of laying down arms.

Page 30: OLC took 10.5 pages to decide it was okay for DOD to kill Awlaki, which is relatively uncontroversial (especially given that the general due process concerns appear to have been dealt with in the first Awlaki memo). It took 5 pages deciding it was okay for CIA to do so. Granted, much of the DOD logic must be repeated, but not all of it can be. And the CIA application was why the memo was written.

Page 30-32: This redaction is the heart of the memo — the heart of the memo’s secret refutation to this blog post. Compare the length of this section with the blog post it responds to.

Page 32: Note the redaction describing the CIA action. I raise the same point raised above, wrt page 18. It may be OLC is saying that because CIA engages in (either) Traditional Military Activities or paramilitary activities, it gets public authority. But the discussion seems to have made no mention of the National Security Act.

Also note footnote 43, which betrays real doubt and no authority.

We note, in addition, that the “lawful conduct of war” variant of the public authority justification, although often described with specific reference to operations conducted by the armed forces, is not necessarily limited to operations by such forces; some descriptions of that variant of the justification, for example, do not imply such a limitation. See, e.g., Frye, 10 Cal. Rptr. 2d at 221 n.2 (“homicide done under a valid public authority, such as execution of a death sentence of killing an enemy in a time of war”); Perkins & Boyce, Criminal Law at 1093 (“the killing of an enemy as an act of war and within the rules of war.”)

I’ll have to go find these cites, but they appear to be totally inapt to the move OLC is making here, which is particularly telling.

Page 33: In one short paragraph, OLC basically says that the CIA case is like the DOD one, which it’s not. (Again, there’s a longish redaction, between the m-dashes, that seems to qualify this as a certain kind of CIA action.) But then in one long footnote, the memo argues that unprivileged combatants are not breaking the law. Which is — as Kevin Jon Heller noted on Twitter — actually not what the government maintains (just as Omar Khadr, because he was convicted on these terms).

DOD’s current Manual for Military Commissions does not endorse the view that the commission of an unprivileged belligerent act, without more, constitutes a violation of the international law of war.

Page 34: This is fairly momentous language, because it presents the notion that CIA should be permitted to do anything with respect to an American DOD can do:

Nor does it indicate that Congress, in closing the identified loophole, meant to place a limitation on the CIA that would not apply to DoD.

Maybe the following redacted passage explains why CIA is permitted to operate outside of the law that the National Security Act does not permit to act under. But on its face this language is fairly dangerous.

Page 34: Note the memo describes the CIA operation as “virtually identical,” but not entirely so. Also note the redaction of language saying CIA would carry out the attack in “accord with [redacted],” which may well refer to the Presidential Finding. If it does, then this memo says a President can authorize the CIA killing of an American on his say-so.

Page 34: Note that footnote 45 invokes a 1984 OLC memo that wrote its justification for non-application of Neutrality Act to people like Oliver North when raising funds for Iran-Contra. You gotta love memos that rely on both State’s self-justification for bombing Cambodia and OLC’s self-justification for ignoring Congressional laws on funding the Contras.

Page 35: Told you the memo included a passage on conspiracy to kill.

Page 35: If I’m not mistaken, FN 46 is to the redacted passage. There are missing citations to other law enforcement related precedents, which might be in there but if so they should be unclassified.

Page 36: I love the language at the end of the first paragraph that says because one law doesn’t prohibit the CIA (and DOD) to kill and American, another law probably doesn’t.

Page 36: Shorter David Barron: 956(a) only applies to terrorists, so therefore it can’t be applied to US conducting asymmetric attacks overseas. Also, it’s a really nice touch that the legislative record comes from then-Senator Joe Biden. And it’s also a nice touch that Tom Daschle’s legislative comments on legislation from 1995 are included in this memo but not in the discussion about the AUMF.

Page 38: Note they now claim Awlaki’s involvement in armed combat involves “planning and recruiting for terrorist attacks.” Based on what Dennis Blair said in a February 2010 hearing, I think the original basis for targeting Awlaki was largely if not exclusively for his recruiting role. But that’s very hard to separate from a First Amendment function, which they don’t deal with here.

Page 38: Note in their discussion of the earlier Barron memo, they redact key bits that the White Paper includes. (See for example the second pages 7 and 8). Some of the White Paper logic may have been developed in connection with John Brennan’s 2011 speech on such issues (which the White Paper cites. Which might mean — though might not — that their logic on imminence changed over time.

Page 38: The redaction at the bottom page hides what in the White Paper is a sentence saying that Americans don’t have immunity. It must also hide some discussion of due process generally.

Page 39: The redactions appear to relate to a balancing test. But the logic between Hamdi and the “continued” and “imminent” language is rather interesting. So are the other jumps between that and the last paragraph on page 40 — these are contiguous in the white paper.

Page 40: Have we seen this Israeli decision as the basis for what amounts to feasible capture?

Page 40: The redactions of the source for the “continue to monitor whether changed circumstances” are interesting — it may be the Barron memo (I’ll check the court filing). In any case, it’s interesting that it’s not the DOD memo, which may be the most recent support for this memo.

Page 41: The redacted line after the Fourth Amendment intro is interesting because the white paper states clearly there that this would not be unreasonable seizure. The redactions in the last paragraph are similar.