History is so cool.

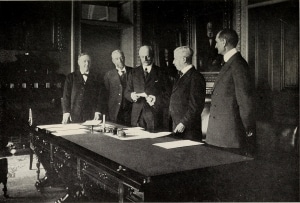

In 1917, Denmark and the US approved a treaty (or more specifically, a convention), the guts of which are summed up in two simple paragraphs:

His Majesty the King of Denmark by this convention cedes to the United States all territory, dominion and sovereignty, possessed, asserted or claimed by Denmark in the West Indies including the Islands of Saint Thomas, Saint John and Saint Croix together with the adjacent islands and rocks.

[snip]

In full consideration of the cession made by this convention, the United States agrees to pay, within ninety days from the date of the exchange of the ratifications of this convention, in the City of Washington to the diplomatic representative or other agent of His Majesty the King of Denmark duly authorized to receive the money, the sum of twenty-five million dollars in gold coin of the United States.

The bulk of the document spells out the details, like how long Denmark has to vacate the premises, what items go with them and what transfers to the new owners, etc.

So OK, the US bought the Virgin Islands from Denmark? What’s the big deal, you ask.

The big deal is a little clearer when you see the “Declaration” at the end, made by US Secretary of State Robert Lansing:

In proceeding this day to the signature of the Convention respecting the cession of the Danish West-Indian Islands to the United States of America, the undersigned Secretary of State of the United States of America, duly authorized by his Government, has the honor to declare that the Government of the United States of America will not object to the Danish Government extending their political and economic interests to the whole of Greenland.

Ah. So the deal was the US gets the Virgin Islands, and Denmark gets Greenland and $25M in gold coin.

And now, Trump wants to void the deal. He ought to be careful, though, because there are other deals like this that the US made that other leaders might want to void.

In 1803, there was a little real estate deal that took three Conventions to lay out all the details (part cash, part debt-swap; involving 3 different nations), but the basic deal was this:

Whereas by the Article the third of the Treaty concluded at St Ildefonso the 9th Vendé miaire an 9/1st October 1800 between the First Consul of the French Republic and his Catholic Majesty [of Spain] it was agreed as follows.

“His Catholic Majesty promises and engages on his part to cede to the French Republic six months after the full and entire execution of the conditions and Stipulations herein relative to his Royal Highness the Duke of Parma, the Colony or Province of Louisiana with the Same extent that it now has in the hand of Spain, & that it had when France possessed it; and Such as it Should be after the Treaties subsequently entered into between Spain and other States.”

And whereas in pursuance of the Treaty and particularly of the third article the French Republic has an incontestible title to the domain and to the possession of the said Territory–The First Consul of the French Republic desiring to give to the Unit ed States a strong proof of his friendship doth hereby cede to the United States in the name of the French Republic for ever and in full Sovereignty the said territory with all its rights and appurtenances as fully and in the Same manner as they have bee n acquired by the French Republic in virtue of the above mentioned Treaty concluded with his Catholic Majesty.[snip]

The Government of the United States engages to pay to the French government in the manner Specified in the following article the sum of Sixty millions of francs independant of the Sum which Shall be fixed by another Convention for the payment of the debts due by France to citizens of the United States.

For the payment of the Sum of Sixty millions of francs mentioned in the preceeding article the United States shall create a Stock of eleven millions, two hundred and fifty thousand Dollars bearing an interest of Six per cent: per annum payable half y early in London Amsterdam or Paris amounting by the half year to three hundred and thirty Seven thousand five hundred Dollars, according to the proportions which Shall be determined by the french Govenment to be paid at either place: The principal of t he Said Stock to be reimbursed at the treasury of the United States in annual payments of not less than three millions of Dollars each; of which the first payment Shall commence fifteen years after the date of the exchange of ratifications:–this Stock Shall be transferred to the government of France or to Such person or persons as Shall be authorized to receive it in three months at most after the exchange of ratifications of this treaty and after Louisiana Shall be taken possession of the name of the Government of the United States.

It is further agreed that if the french Government Should be desirous of disposing of the Said Stock to receive the capital in Europe at Shorter terms that its measures for that purpose Shall be taken So as to favour in the greatest degree possible the credit of the United States, and to raise to the highest price the Said Stock.

Again, lots of details passed over in these three conventions, but the essence of deal is simple: the US gets the land, and France gets cash and a settlement on the debts they owe to US citizens.

Perhaps if Trump wants to revoke by fiat the Convention with Denmark over the Virgin Islands and Greenland, President Macron might start thinking he should do the same with Trump over Louisiana.

His Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias, agrees to cede to the United States, by this convention, immediately upon the exchange of the ratifications thereof, all the territory and dominion now possessed by his said Majesty on the continent of America and in adjacent islands, the same being contained within the geographical limits herein set forth, to wit: [geographic details omitted]

[snip]

In consideration of the cession aforesaid, the United States agree to pay at the Treasury in Washington, within ten months after the exchange of the ratifications of this convention, to the diplomatic representative or other agent of His Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias, duly authorized to receive the same, seven million two hundred thousand dollars in gold.

Again, lots of details omitted, but these two paragraphs lay out the broad parameters of the deal. Now imagine Putin wanting it back.

See, that’s the thing about international agreements. If you decide they aren’t worth the paper they are written on, other folks might agree with you and act accordingly.

Sarah Palin might want to brush up on her Russian, and I may need to be working on my French.

ADDENDUM

Don’t know how I could have forgotten this one from 1819, but I hit publish before it occurred to me.

His Catholic Majesty [of Spain] cedes to the United States, in full property and sovereignty, all the territories which belong to him, situated to the eastward of the Mississippi, known by the name of East and West Florida. The adjacent islands dependent on said provinces, all public lots and squares, vacant lands, public edifices, fortifications, barracks, and other buildings, which are not private property, archives and documents, which relate directly to the property and sovereignty of said provinces, are included in this article. The said archives and documents shall be left in possession of the commissaries or officers of the United States, duly authorized to receive them.

[snip]

The United States, exonerating Spain from all demands in future, on account of the claims of their citizens to which the renunciations herein contained extend, and considering them entirely cancelled, undertake to make satisfaction for the same, to an amount not exceeding five millions of dollars.

Lots of other details omitted, but you get the idea.

Perhaps Trump can ask one of his minions how to say “Welcome to Mar-a-Lago” in Spanish?