On April 12, the same day that Judge Maryellen Noreika finally issued her opinions rejecting Hunter Biden’s motions to dismiss based on immunity and selective and vindictive prosecution, Hunter filed a notice of interlocutory appeal of all of Scarsi’s opinions. My Hunter Biden page has been updated to reflect these developments.

I think, but am not certain, that the notice of appeal came after Noreika released her opinions, and so might be a response to it.

It’s unclear what basis Lowell believes he has for an interlocutory appeal. At the initial appearance, Judge Scarsi had instructed Abbe Lowell to brief whether he could file such an appeal for the diversion agreement, which Lowell failed to do in his motions to dismiss. One possibility is that Lowell plans to argue that Delaware, as the first filed case, should have ruled first. He argued this in a February motion to continue the similar filings.

“[W]hen cases between the same parties raising the same issues are pending in two or more federal districts, the forum of the first-filed action should generally be favored.” Heieck v. Federal Signal Corp., 2019 WL 1883895, at *2 (C.D. Cal., Mar. 11, 2019). This approach maximizes judicial economy, avoids the possibility of inconsistent judgments, and minimizes any unnecessary burden on the two Courts’ or the parties’ resources.

If that’s the case, however, the facial similarity of the two diversion agreement opinions might doom an appeal that would be extremely unlikely to work anyway. Both judges ruled that because Probation did not sign the diversion agreement, it was not in place and so Hunter got no immunity from it. The rulings are not inconsistent on their key point (though are in other key ways).

That said, even though neither side formally called attention to Judge Scarsi’s rulings, Judge Noreika noted it in a really confusing footnote.

5 This Court recognizes that, relying largely on California and Ninth Circuit law, the judge overseeing tax charges brought against Defendant in the Central District of California decided that Probation’s approval is “a condition precedent to performance, not to formation,” and that the absence of Probation’s approval means that “performance of the Government’s agreement not to prosecute Defendant is not yet due.” United States v. Biden, No. 2:23-cr-00599-MCS-1, 2024 WL 1432468, at *8 & *10 (C.D. Cal. Apr. 1, 2024). Neither of those issues nor that law was raised by the parties before this Court.

I don’t know what “law” she’s referring to — possibly the Ninth Circuit precedent Scarsi relied on? If that’s the case, then she would be affirming precisely the problem Lowell pointed out: by relying on different precedents, Scarsi has created inconsistency in the judgments.

But she’s flat out wrong that the government’s arguments about whether Probation’s signature was a condition precedent to the formation or the performance of the diversion agreement; it was central to the government’s response.

Applying contract law principles, the approval of U.S. Probation was a condition precedent to the formation of the contract. “A condition may be either a condition precedent to the formation of a contract or a condition precedent to performance under an existing contract.” W & G Seaford Assocs. v. Eastern Shore Mkts., Inc., 714 F.Supp. 1336, 1340 (D.Del.1989) (citing J. Calamari & J. Perillo, Contracts § 11–5, at 440 (3d ed.1987)); Williston on Contracts §38.4. “In the former situations, the contract itself does not exist unless and until the condition occurs.” Id.; Willison on Contracts § 38.7.

There is a bigger difference between the two opinions, though: how they understand Probation’s decision not to sign the plea. As I’ve noted, Scarsi effectively rewrote one of the exhibits he relied on to claim that Probation was not part of revisions to the diversion agreement. As I’ll show, Noreika does not deny that Probation was a part of those revisions, but nevertheless, with no explanation, held that Probation didn’t approve the agreement.

And that’s important because Noreika doesn’t explain her own intervention in the approval of the diversion agreement, effectively intervening in a prosecutorial decision, a problem I pointed out in this post. Indeed, the opinion is consistent with Margaret Bray refusing to sign the diversion agreement because of some interaction Bray had with Judge Noreika before the hearing.

Before I explain why, let me emphasize, Hunter Biden is well and truly fucked. What I’m about to say is unlikely to matter, and if it does, it’s likely only to matter after two judges who seem predisposed against Hunter make evidentiary decisions that will increase the political cost of two trials, if and when juries convict Hunter, and after those same judges rule on whether Hunter can remain out on pretrial release pending the appeal of this mess, which Scarsi, especially, is unlikely to do. Worse still, after I laid out all the ways Judge Scarsi had made his own opinion vulnerable on appeal, he ruled against Abbe Lowell’s attempt to certify all the evidence Scarsi said had not come in properly. Scarsi is using procedural reasons to protect his own failures in his opinions. He’s entitled to do so; he’s the judge! So what I’m about to write does not change the fact that Joe Biden’s son is well and truly fucked.

Judge Noreika refashions her intervention in the plea hearing

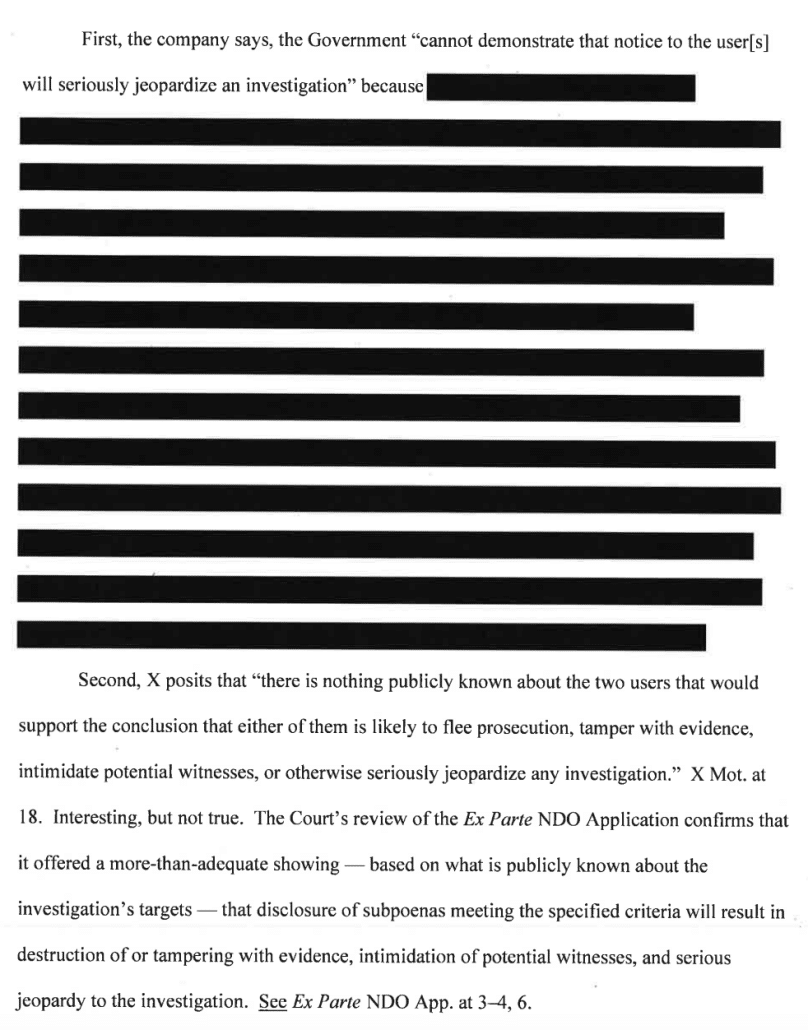

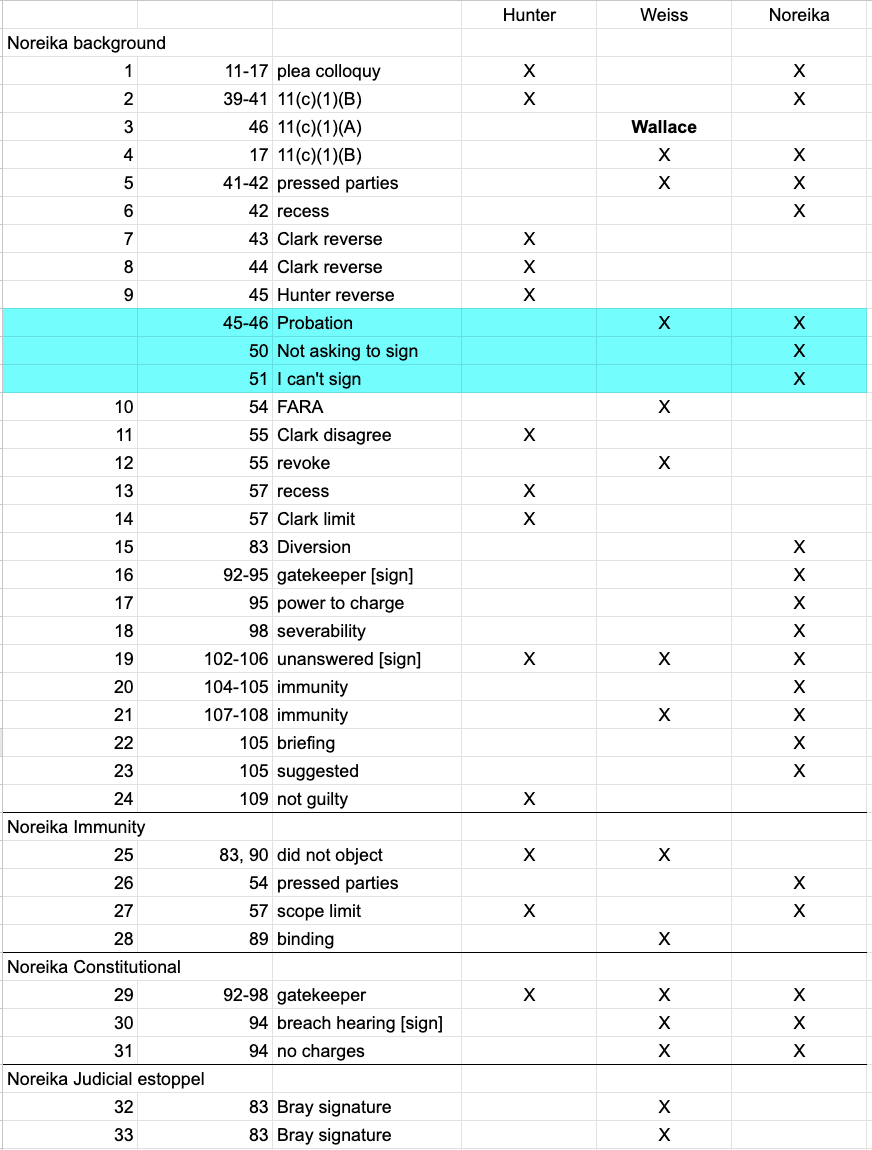

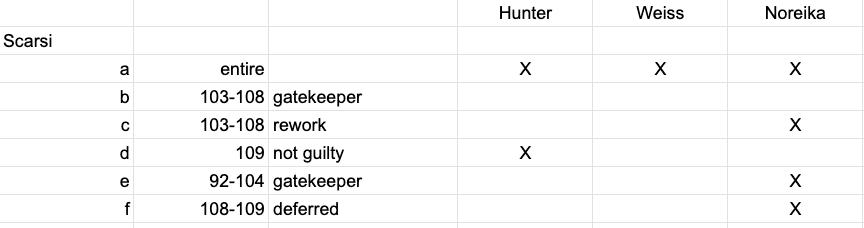

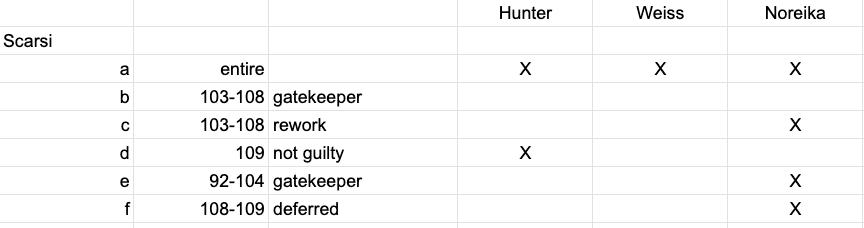

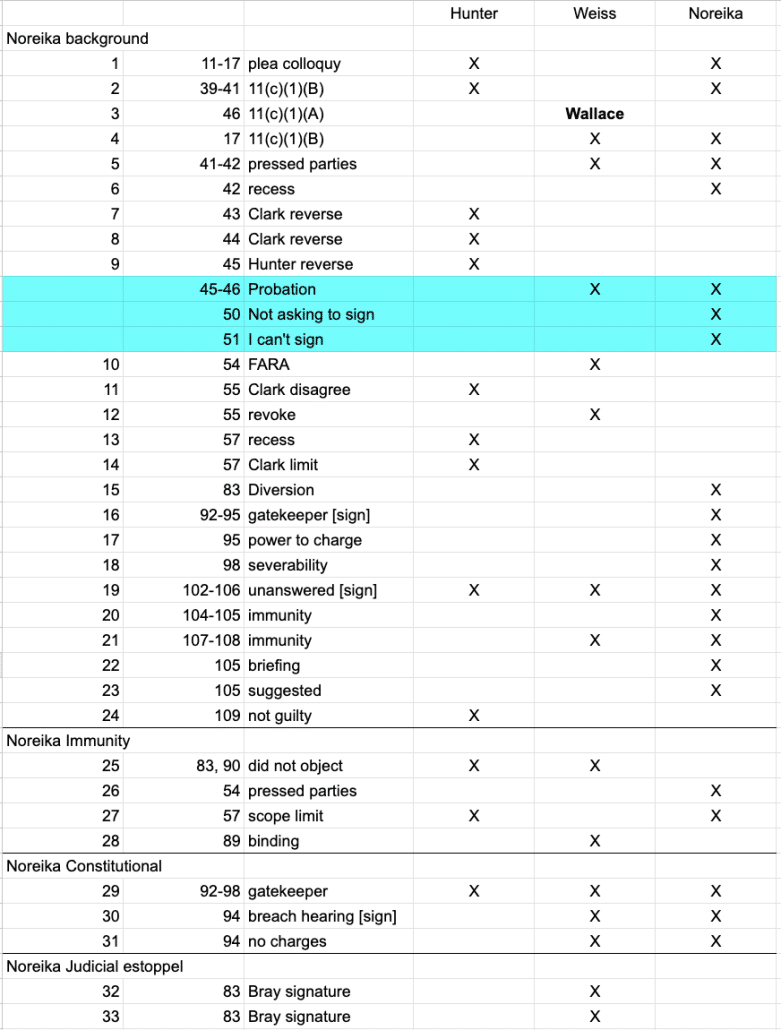

In his omnibus ruling on Hunter’s motions to dismiss, Judge Scarsi only cited the plea hearing transcript six times, entirely focused on the end of the discussion (the Xs describe who is being quoted in the citation).

The parties submitted the Plea Agreement and the Diversion Agreement to United States District Judge Maryellen Noreika in advance of a scheduled July 26, 2023, Initial Appearance and Plea Hearing. (See Machala Decl. Ex. 1 (“Del. Hr’g Tr.”), ECF No. 25-2.) At the hearing, after questioning Defendant and the parties, the District Court Judge expressed concerns regarding both Defendant’s understanding of the scope of the immunity offered by the Diversion Agreement and the appropriateness of the District Court’s role in resolving disputes under the Diversion Agreement. (Del. Hr’g Tr. 103–08.) The District Court Judge asked the parties to rework the agreements and provide additional briefing regarding the appropriate role of the District Court in resolving disputes under the Diversion Agreement. (Id.) At the hearing, Defendant entered a plea of not guilty to the tax charges then pending in Delaware. (Id. at 109.)

[snip]

6 This observation begs a question regarding another provision, the parties’ agreement that the United States District Court for the District of Delaware would play an adjudicative role in any alleged material breach of the agreement by Defendant. (Diversion Agreement § II(14).) The judge overseeing the action in Delaware questioned whether it was appropriate for her to play this role. (Del. Hr’g Tr. 92–104.) The Court is uncertain as to whether the parties understood the Probation Officer also to have a role in approving the breach-adjudication plan in her capacity as an agent of the court. See 18 U.S.C. § 3602. But these issues need not be resolved to adjudicate the motion.

[snip]

On July 26, 2023, the district judge in Delaware deferred accepting Defendant’s plea so the parties could resolve concerns raised at the plea hearing. (See generally Del. Hr’g Tr. 108–09.)

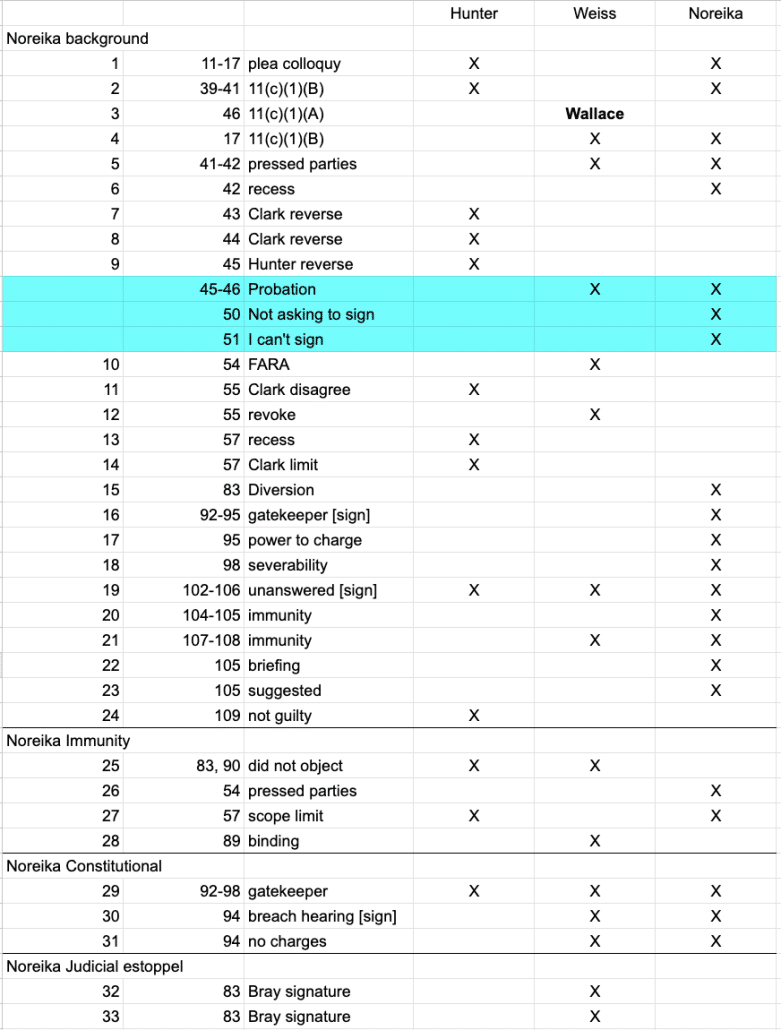

By contrast, Judge Noreika cited her own hearing transcript 33 times: 24 times in her background section, four times in her sua sponte section deeming the extent of Hunter’s immunity uncertain, three times in a sua sponte section that intruded on the Executive’s prosecutorial function where she said it would be unconstitutional to intrude on the Executive’s prosecutorial function, and twice more in a section misrepresenting the focus of Hunter’s judicial estoppel argument. 21 of her citations were substantially to her own comments in the hearing.

The degree to which this opinion makes claims about what Noreika actually did at the plea hearing matters. Not only does Noreika fluff the nature of her own intervention, but her discussion left out critical discussion about the nature of approvals required for the diversion agreement (including but not limited to those marked in blue above). That includes five complaints about the fact that she was not asked to sign the diversion agreement and a key intervention in which she expressed an opinion on the scope of the authority for Margaret Bray to intervene in the diversion agreement.

Additionally, in one place, she misrepresented the transcript in a way that minimized her own intervention.

That is, Noreika used her own opinion to refashion the intervention she made in the plea hearing.

The last example — when she misrepresented the transcript — is instructive. As noted, though neither side made this argument, Noreika nevertheless spent 2.5 pages arguing that the scope of the immunity grant in the diversion agreement was not sufficiently clear to be contractually enforceable. In it, she claimed that the uncertainty over the scope of the immunity, and not her own intervention, was the only reason the plea collapsed, a claim she carries over to the selective and vindictive prosecution opinion.

Then, she declined to accept Chris Clark’s oral modification of the immunity provision to include just gun, tax, and drug crimes.

Pressing the parties on their respective understandings of what conduct was protected by the immunity from prosecution led to a collapse of the agreement in court. (D.I. 16 at 54:10-55:22).

Apparently acknowledging that the immunity provision as initially drafted was not sufficiently definite, the parties attempted to revise the scope of the immunity conferred by the Division Agreement orally at the July 2023 hearing. (See D.I. 16 at 57:19-24 (“I think there was some space between us and at this point, we are prepared to agree with the government that the scope of paragraph 15 relates to the specific areas of federal crimes that are discussed in the statement of facts which in general and broadly relate to gun possession, tax issues, and drug use.”)). The Court recognizes that Delaware law permits oral modifications to contracts even where the contract explicitly provides that modifications must be in signed writings, as the Diversion Agreement did here. (See D.I. 24, Ex. 1 ¶ 19 (“No future modifications of or additions to this Agreement, in whole or in part, shall be valid unless they are set forth in writing and signed by the United States, Biden and Biden’s counsel.”)). That being said, although the government asserted that that oral modification was binding (D.I. 16 at 89:9-14), the Court has never been presented with modified language to replace the immunity provision found in Paragraph 15. [my emphasis]

This is a nutty argument to begin with: Neither side is arguing that gun crimes were not included in the diversion immunity (to which elsewhere she limits her review); neither is even arguing there was uncertainty as to the application of immunity to tax and drug crimes. The only uncertainty pertained to FARA (and that only because — as Noreika herself described it, Leo Wise “revoked” a signed agreement).

This discussion is especially problematic because, elsewhere, she left out a crucial part of her own invitation to clarify the immunity language, which the opinion describes this way:

The Court also suggested that the parties clarify the scope of any immunity conferred by the immunity provision of the Diversion Agreement. (Id. at 105:16-22).

Noreika’s reference to the government’s assertion that Chris Clark orally modified the scope of immunity by agreeing to limit it to tax, guns, and drugs pertains to this comment from Leo Wise:

Obviously this paragraph has been orally modified by counsel for Mr. Biden and we would — I’m not going to attempt to paraphrase it. I don’t want to make the record muddy. The statement by counsel is obviously as Your Honor acknowledged a modification of this provision, and that we believe is binding.

Importantly, when Noreika invited the parties to clarify the diversion scope (claiming all the while she was not trying to tell the parties how to negotiate), she treated the Clark comment as having been orally modified.

you might, though I’m not trying to tell you how to negotiate the Diversion Agreement, you might fix that one paragraph that you have orally modified today.

At the hearing, Noreika treated the diversion scope as orally modified, but in this opinion she not only omits mention that she did so, but she suggests that because the parties didn’t modify the contract about prosecution declination to her liking, then it is not binding.

She’s claiming to have no role in the drafting process, and then she’s demanding changes in the contract that she already said had been adopted, a contract in which she repeatedly says would be unconstitutional for her to intervene.

The logistics of the asymmetric knowledge of Margaret Bray’s non signature

All this matters because of something else: Judge Noreika’s opinion exhibits knowledge of something to which she was not a witness. It arises from the logistics from that plea hearing.

As I noted, while claiming he was ruling on the diversion agreement as an unambiguous contract, Judge Scarsi nevertheless relied on extrinsic evidence — a declaration from AUSA Benjamin Wallace. Before Wallace submitted the declaration before Judge Scarsi, Wallace withdrew his appearance before Judge Noreika, in a letter signed as a Delaware AUSA reporting to US Attorney David Weiss, someone who is no longer before that docket.

Given that Wallace referred to final agreements four times as drafts in the declaration, it deserves close scrutiny.

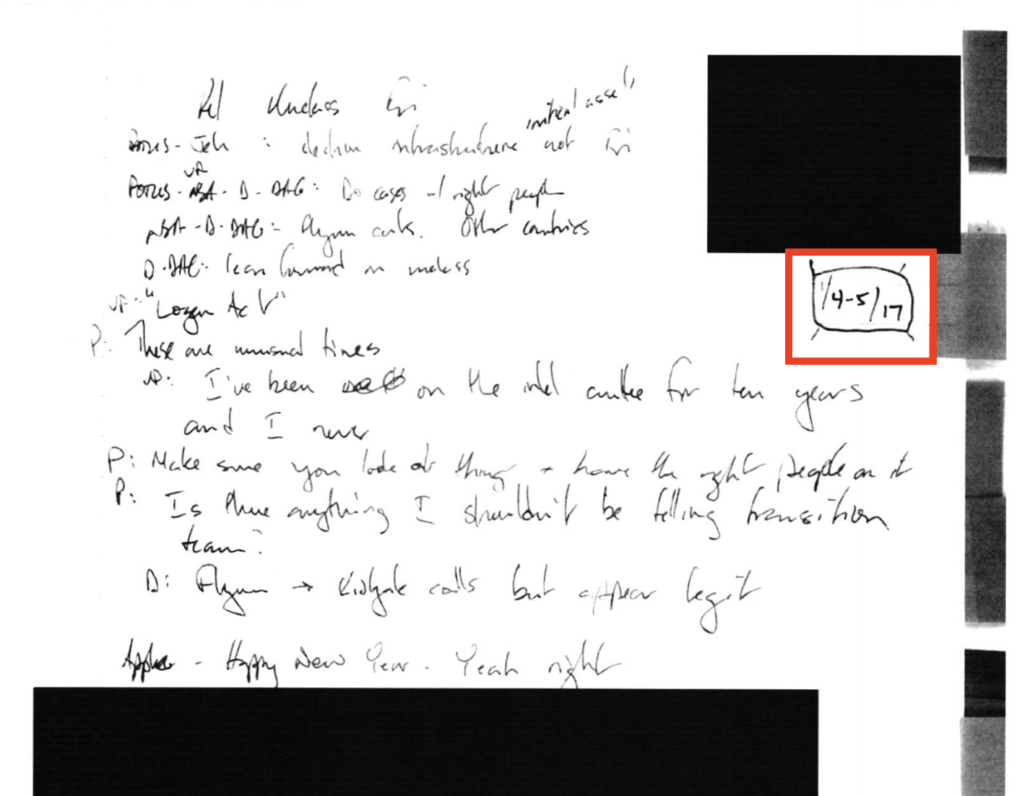

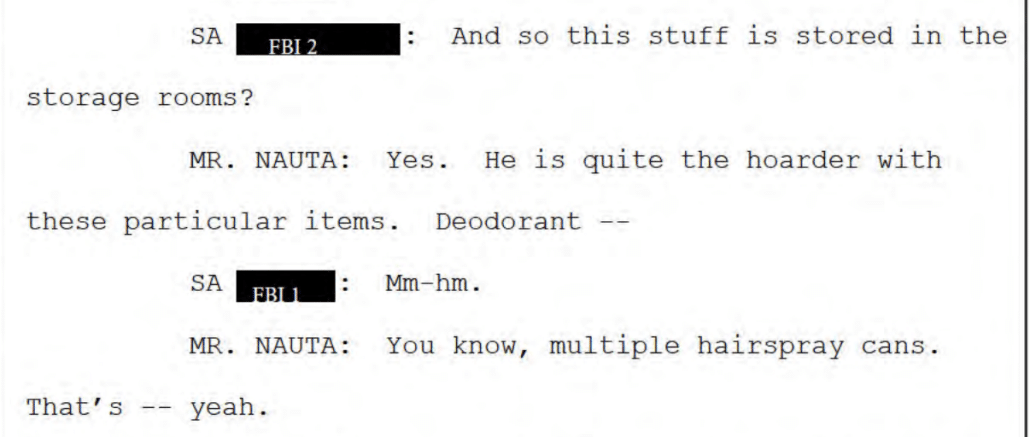

In it, Wallace described that before Judge Noreika took the bench and while Chris Clark and Leo Wise were signing the plea agreement and diversion agreement on July 26, he told Margaret Bray that she could soon sign the diversion agreement. According to Wallace, she “expressly declined to sign the draft diversion agreement.”

3. Before the District Judge took the bench, the parties signed the draft plea agreement in No. 23-mj-274 and the draft diversion agreement in No. 23-cr-61. Leo J. Wise, Special Assistant United States Attorney, signed on behalf of the government. Mr. Biden and his attorney, Christopher J. Clark, signed on behalf of Mr. Biden.

4. While Mr. Biden, Mr. Clark, and Mr. Wise were signing the two agreements, I approached the Chief United States Probation Officer for the District of Delaware, Margaret M. Bray, to tell her that the draft diversion agreement would be ready for her signature shortly. Ms. Bray expressly declined to sign the draft diversion agreement.

In the Los Angeles motions hearing, Abbe Lowell suggested there was something funny about this timing and asked a more important question: Why the head of Probation was not the one submitting the declaration.

MR. LOWELL: It probably — well, it matters in the following way. If what was happening was questions were being raised, and that’s why she didn’t do it, or for any other reason, after she manifested her agreement in what she sent to the court on July 20th or what the Government said, then it probably doesn’t matter.

I don’t think it really matters why at that moment and when it doesn’t — when it happened. I’m just saying that I think the sequence of what happened on July the 26th is murky, at best.

And I’d like to have Ms. Bray be the one to give a declaration, not somebody else that talks about what happened and when it happened and why it happened. I was there, so it would be good if the person who did it, did it. But that’s not what they submitted.

But Noreika’s opinion makes it clear why the timing and substance matters — and why Margaret Bray, the person that both Noreika and Scarsi have ruled effectively vetoed this agreement by not signing it, should have been the one submitting a declaration.

Assuming Wallace’s description of the timing is correct — that this happened while Clark and Wise were busy signing the documents themselves and before Judge Noreika entered the courtroom — then it would create an asymmetry of knowledge among the participants in the hearing. Bray, who never spoke at the hearing, would know she had refused to sign. Wallace would know and therefore did know when he made his single comment at the hearing: agreeing that if the immunity language had been included in the plea agreement rather than the diversion agreement, it would change the rule under which Judge Noreika was reviewing the plea agreement.

THE COURT: And if it were included in the Memorandum of Plea Agreement, would that make this plea agreement one pursuant to Rule 11(c)(1)(A)?

MR. WALLACE: It would.

Did Wallace make this comment because of something Bray told him before the hearing? Importantly, Noreika relies on this assent to use her own uncertainty about the proper clause under which to consider the plea to replace authority to alter the diversion. That is, Noreika effectively used Wallace’s assent to suggest she had the authority to draft the diversion agreement. If he learned that Noreika had a concern about that clause from Bray, it would amount to an ex parte communication between the prosecution and the judge.

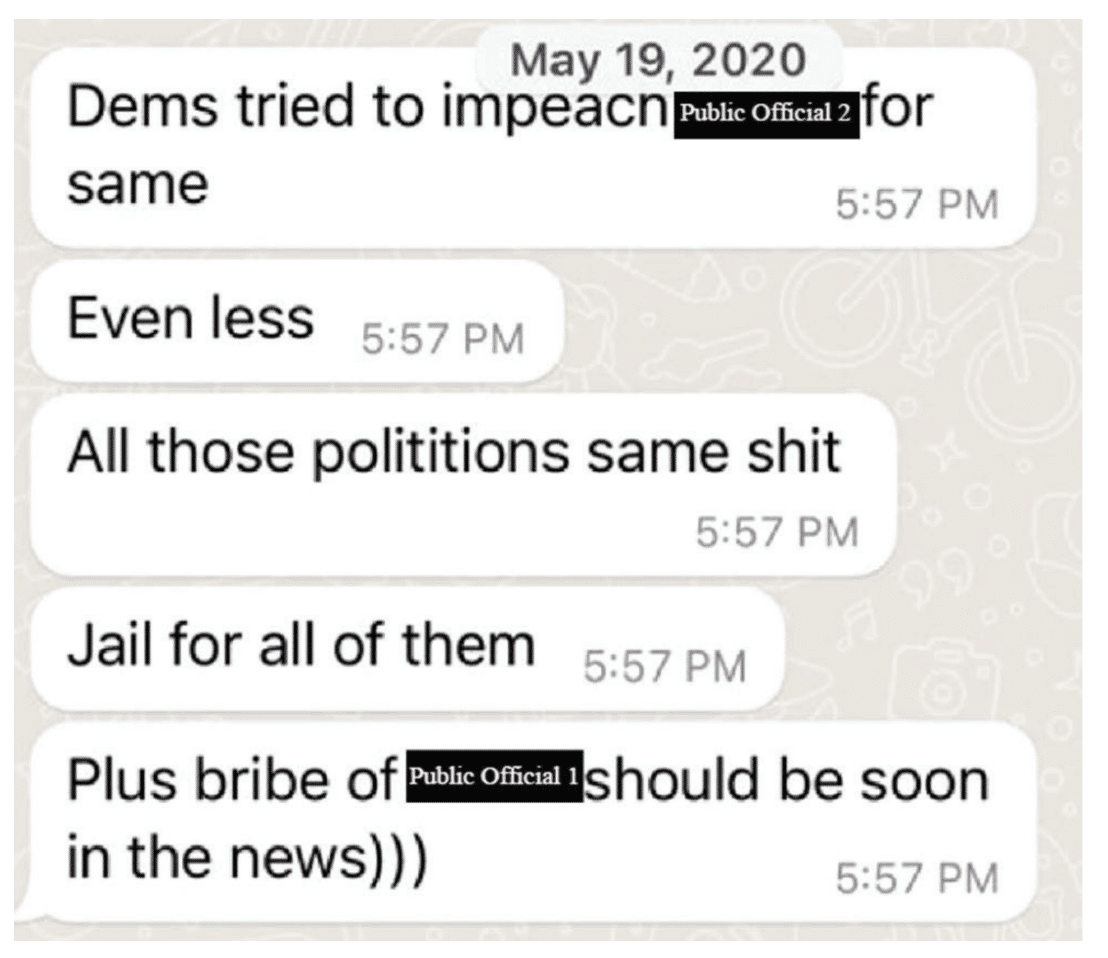

Over the course of the hearing — most notably, between the time Leo Wise made a comment about the limits of Probation’s involvement and the time when Wise said the diversion agreement would only go into effect after Bray signed it — Wallace could have shared that knowledge with the other prosecutors. That is, it is possible but uncertain whether prosecutors used this asymmetric knowledge to get out of the plea deal.

But Hunter Biden’s team would never know this occurred, which is consistent with Chris Clark’s repeated statements that he believed Probation had already approved the diversion, which Weiss’ team did not dispute.

And, because all this happened before she took the bench, Judge Noreika should not have known that Ms. Bray refused to sign it. She should not have known it, that is, unless she and Margaret Bray had discussions before the hearing about Bray not signing the agreement.

If they did, then Bray’s failure to sign the diversion agreement would effectively serve as a proxy disapproval from Judge Noreika. It would amount to Judge Noreika, who is neither a party to this agreement nor someone authorized to approve or disapprove it, vetoing the agreement by instructing Bray not to sign it.

Noreika exhibited knowledge of Bray’s lack of signature

There are three times in Noreika’s opinion where she exhibits some knowledge that Bray had not signed that diversion agreement before the hearing.

First, in her treatment of Hunter’s half-hearted attempt to claim that judicial estoppel prevents the prosecution from had not started yet, she described believing at the time and still believing that the government did not believe the diversion period started until Bray signed the agreement.

As the Court understood that statement at the time, the government’s position was that the diversion period did not begin to run until Probation’s approval was given – approval to be indicated by a signature on the Diversion Agreement itself. That is, the Diversion Agreement would not become effective until approval through signature was given. That continues to be the Court’s understanding today.

Having such a belief at the time would only make sense if she knew the diversion had not yet been signed and, given the logistics, that would seemingly require having known before Bray told Wallace she would not sign it.

In her section rejecting Hunter’s argument that by recommending Hunter for diversion on July 19 and then, along with the parties, tweaking the diversion agreement, Noreika offered no reason why she was unpersuaded that Bray had indicated her assent by participating in those changes, something about which her courtroom deputy received emails.

Defendant nevertheless suggests that Probation’s approval may be implied from the fact that Probation recommended pretrial diversion and suggested revisions to the proposed agreement before the July 2023 hearing. (D.I. 60 at 18-19). The Court disagrees. That Defendant was recommended as a candidate for a pretrial diversion program does not evidence Probation’s approval of the particular Diversion Agreement the parties ultimately proposed. Probation recommended that Defendant was of the type of criminal defendant who may be offered pretrial diversion and also recommended several conditions that Probation thought appropriate. (D.I. 60, Ex. S at Pages 8-9 of 9). That is fundamentally different than Probation approving the Diversion Agreement currently in dispute before the Court. And as to Probation’s purported assent to revisions to the Diversion Agreement (D.I. 60, Ex. T at Page 2 of 28), Defendant has failed to convince the Court that the actions described can or should take the place of a signature required by the final version of an agreement, particularly when the parties execute the signature page. Ultimately, the Court finds that Probation did not approve the Diversion Agreement. [my emphasis]

Importantly, Noreika does not address the scope via which Probation, having already approved the parts they would oversee, could reject this deal.

But the most important evidence that Judge Noreika knew of something during the hearing to which she was not a direct witness was a question she posed — invoking the first person plural — suggesting that Probation should not approve the deal.

THE COURT: All right. Now, I want to talk a little bit about this agreement not to prosecute. The agreement not to prosecute includes — is in the gun case, but it also includes crimes related to the tax case. So we looked through a bunch of diversion agreements that we have access to and we couldn’t find anything that had anything similar to that.

So let me first ask, do you have any precedent for agreeing not to prosecute crimes that have nothing to do with the case or the charges being diverted?

MR. WISE: I’m not aware of any, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Do you have any authority that says that that’s appropriate and that the probation officer should agree to that as terms, or the chief of probation should agree to that as terms of a Diversion Agreement?

MR. WISE: Your Honor, I believe that this is a bilateral agreement between the parties that the parties view in their best interest. I don’t believe that the role of probation would include weighing whether the benefit of the bargain is valid or not from the perspective of the United States or the Defendant. (46)

Not only did Noreika suggest that some collective “we” had been reviewing diversion agreements together, but she suggested Bray could still reject the deal based on the scope of David Weiss’ prosecutorial decision. She suggested Bray could dictate to Weiss how much he could include in a declination statement.

This is precisely the kind of usurpation of the Executive’s authority that Noreika said would be unconstitutional. Which was precisely Leo Wise’s response: he responded that Bray did not have the authority to opine that the parties had entered into a contract that did not sufficiently protect the interests of the United States.

Shortly after that exchange, Judge Noreika started complaining that she was not asked to sign the diversion agreement.

I think what I’m concerned about here is that you seem to be asking for the inclusion of the Court in this agreement, yet you’re telling me that I don’t have any role in it, and you’re leaving provisions of the plea agreement out and putting them into an agreement that you are not asking me to sign off on. (50)

[snip]

But then it would be a plea under Rule (c)(1)(A) if the provision that you have put in the Diversion Agreement which you do not have anyplace for me to sign and it is not in my purview under the statute to sign, you put that provision over there. So I am concerned that you’re taking provisions out of the agreement, of a plea agreement that would normally be in there. So can you — I don’t really understand why that is. (51)

[snip]

All right. Now I have reviewed the case law and I have reviewed the statute and I had understood that the decision to offer the defendant, any defendant a pretrial diversion rest squarely with the prosecutor and consistent with that, you all have told me repeatedly that’s a separate agreement, there is no place for me to sign off on it, and as I think I mentioned earlier, usually I don’t see those agreements. But you all did send it to me and as we’ve discussed, some of it seems like it could be relevant to the plea. (92)

[snip]

THE COURT: First it got my attention because you keep telling me that I have no role, I shouldn’t be reading this thing, I shouldn’t be concerned about what’s in these provisions, but you have agreed that I will do that, but you didn’t ask me for sign off, so do you have any precedent for that? (94)

[snip]

What’s funny to me is you put me right smack in the middle of the Diversion Agreement that I should have no role in, you plop meet [sic] right in there and then on the thing that I would normally have the ability to sign off on or look at in the context of a Plea Agreement, you just take it out and you say Your Honor, don’t pay any attention to that provision not to prosecute because we put it in an agreement that’s beyond your ability. (104)

The first two of these citations — the ones that precede Leo Wise’s “revocation” of the plea deal — are not mentioned in Noreika’s opinion. The other three are invoked several times in references to the transcript (including three of the references made by Judge Scarsi), but in none of those references does Noreika admit she was demanding the authority to sign off on the diversion agreement.

The Court pressed the government on the propriety of requiring the Court to first determine whether Defendant had breached the Diversion Agreement before the government could bring charges – effectively making the Court a gatekeeper of prosecutorial discretion. (D.I. 16 at 92:22-95:17).

[snip]

The parties attempted to analogize the breach procedure to a violation of supervised release, but the Court was left with unanswered questions about the constitutionality of the breach provision, leaving open the possibility that the parties could modify the provision to address the Court’s concerns. (Id. at 102:5-106:2).

She presented these demands to sign off on the diversion agreement as the exact opposite of what they were: a concern that she would be usurping the role of prosecutors if the diversion went into effect, when in fact she was concerned that she wasn’t being given opportunity to veto prosecutors’ non-prosecution decision.

Notably, Judge Noreika mentions Chris Clark’s failure to object after Leo Wise (after such time as Wallace could have told him that Bray did not sign the diversion agreement) said the agreement would go into effect when Probation signed it.

4 Although not part of the Court’s decision, the Court finds it noteworthy that the government clearly stated at the hearing that “approval” meant “when the probation officer . . . signs it” and Defendant offered no objection or correction to this. (D.I. 16 at 83:13-17 & 90:13-15).

She doesn’t mention her own failure to correct Wise when he said she could sign the diversion agreement.

I think practically how this would work, Your Honor, is if Your Honor takes the plea and signs the Diversion Agreement which is what puts it into force as of today, and at some point in the future we were to bring charges that the Defendant thought were encompassed by the factual statement in the Diversion Agreement or the factual statement in the Plea Agreement, they could move to dismiss those charges on the grounds that we had contractually agreed not to bring charges encompassed within the factual statement of the Diversion Agreement or the factual statement of the tax charges.

This doesn’t prove that Judge Noreika asked Margaret Bray not to sign the diversion before Bray told Wallace she would not sign it. But it does show that Noreika thought one of the two of them, either she or Bray, should have the power to veto a prosecutorial decision.

And Judge Noreika refashions her intervention in the plea hearing to obscure that point.

Noreika shifts her demands for sign-off power

As noted, even in spite of her minute order that reflects she deferred agreement on both the plea agreement and the diversion agreement in which it would be unconstitutional for her to intervene, Noreika suggests that the plea fell apart only because of the dispute about immunity that started after she had already intervened in signing authority.

She does ultimately deal with her demands — in a section reserving veto authority over the diversion agreement based on her authority to dictate public policy to prosecutors!

In a truly astonishing section, Noreika applies contract law about a diversion she claims, with no basis, has been made part of the plea deal and uses it to claim she could veto a prosecutorial decision.

Contractual provisions that are against public policy are void. See Lincoln Nat. Life Ins. Co. v. Joseph Schlanger 2006 Ins. Tr., 28 A.3d 436, 441 (Del. 2011) (“[C]ontracts that offend public policy or harm the public are deemed void, as opposed to voidable.”). “[P]ublic policy may be determined from consideration of the federal and state constitutions, the laws, the decisions of the courts, and the course of administration.” Sann v. Renal Care Centers Corp., No. 94A-10-001, 1995 WL 161458, at *5 (Del. Super. Ct. Mar. 28, 1995). Embedded in the Diversion Agreement’s breach procedure is a judicial restriction of prosecutorial discretion that may run afoul of the separation of powers ensured by the Constitution. See, e.g., United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 693 (1974) (“[T]he Executive Branch has exclusive authority and absolute discretion to decide whether to prosecute a case . . . .”); United States v. Wright, 913 F.3d 364, 374 (3d Cir. 2019) (“[A] court’s power to preclude a prosecution is limited by the separation of powers and, specifically, the Executive’s law-enforcement and prosecutorial prerogative.”).

At the hearing in July 2023, the Court expressed concern over the breach provision of the Diversion Agreement and the role the parties were attempting to force onto the Court.8 (See D.I. 16 at 92:12-98:19). In the Court’s view, the parties were attempting to contractually place upon the Judicial Branch a threshold question that would constrain the prosecutorial discretion of the Executive Branch as to the current Defendant. As the government admitted, even if there were a breach, no charges could be pursued against Defendant without the Court first holding a hearing and making a determination that a breach had occurred. (Id. at 94:10-15). If the Court did not agree to follow the procedure, no charges could be pursued against Defendant. (Id. at 94:16-20). Mindful of the clear directive that prosecutorial discretion is exclusively the province of the Executive Branch, the Court was (and still is) troubled by this provision and its restraint of prosecutorial decisions. Although the parties suggested that they could modify this provision to address the Court’s concerns (id. at 103:18-22), no language was offered at the hearing or at any time later. And no legal defense of the Diversion Agreement’s breach provision has been provided to the Court – the deals fell apart before any supplemental briefing was received.

Even if the Court were to find the Diversion Agreement was approved by Probation as required and the scope of immunity granted sufficiently definite, the Court would still have questions as to the validity of this contract in light of the breach provision in Paragraph 14. To be clear, the Court is not deciding that the proposed breach provision of Paragraph 14 is (or is not) constitutional. Doing so is unnecessary given that the Diversion Agreement never went into effect. The Court simply notes that, if the Diversion Agreement had become effective, the concerns about the constitutionality of making this trial court a gatekeeper of prosecutorial discretion remain unanswered. And because there is no severability provision recited in the contract, more would be needed for the Court to be able to determine whether this provision could properly remain in the Diversion Agreement and whether the contract could survive should the Court find it unconstitutional or refuse to agree to serve as gatekeeper.

This entire opinion is rife with examples where Judge Noreika placed herself in a contract to which she was never a party, effectively dictating what David Weiss could include in a prosecutorial declination. But she claims she’s doing the opposite, not snooping into a contract that should only be before her for its immunity agreement, but instead protecting prosecutors’ ability to renege on a declination decision.

I will leave it to the lawyers to make sense of the legal claims here.

But there’s a procedural one that Noreika overlooks.

As noted here, Scarsi’s ruling that the diversion agreement remains binding on the parties conflicts with Noreika’s claim that the problem here is that no one briefed her to placate her complaints.

There are other places where Scarsi’s ruling and Noreika’s conflict — specifically about Probation’s involvement in revisions to the terms that Probation actually governs. But if Scarsi is right, than Noreika’s order withdrawing the briefing order was withdrawn improperly.