Aileen Cannon’s Calvinball Special Master

In the first paragraph of her order reversing Raymond Dearie’s order that Trump verify the inventory DOJ provided, Aileen Cannon identified three documents by name: Dearie’s amended case management plan, dated September 23, Trump’s objections, which were originally sent to Dearie on September 25 but which she may have only seen on September 28, and a government filing she renames, which was originally titled, “Motion to Modify and Adopt the Amended Case Management Plan with Comments on the Amended Plan and Plaintiff’s Objections.” That was filed on September 27.

THIS CAUSE comes before the Court upon the Amended Case Management Plan (the “Plan”) [ECF No. 112], filed on September 23, 2022. The Court has reviewed the Plan, Plaintiff’s Objections [ECF No. 123-1], Defendant’s Response to Plaintiff’s Objections and Motion to Modify and Adopt the Plan [ECF No. 121], and the full record.

Later in her order, when she discusses Dearie’s own order that Trump confirm the inventory before the start of the designations, she describes the deadline he set for the inventory verification as September 30, then notes in a footnote that he modified that deadline in an interim report to her on September 27.

In addition to requiring Defendant to attest to the accuracy of the Inventory, the Plan also requires Plaintiff, on or before September 30, 2022, to lodge objections to the Inventory’s substantive contents.2

2 The Special Master’s Interim Report No. 1 modified this deadline to October 7, 2022 [ECF No. 118 p. 2].

Those two details are a tell to understand what, bureaucratically, Cannon imagines she did on Thursday. On Thursday, she was overruling Dearie’s plan as it existed on September 23, not as it existed on September 27. She was effectively taking over the review starting on September 23, but without telling anyone that or explaining what deadlines applied.

It’s a way — and was used as a way in this instance — to make Dearie entirely superfluous, a mere showpiece to give her own direct intervention to give Trump his way the patina of legitimacy.

Start with Cannon’s order appointing Dearie, dated September 15. It required that Dearie submit a plan to her within ten days, so by September 25.

Within ten (10) calendar days following the date of this Order, the Special Master shall consult with counsel for the parties and provide the Court with a scheduling plan setting forth the procedure and timeline—including the parties’ deadlines—for concluding the review and adjudicating any disputes.

She set a five day deadline for the parties to object to that order, after which she would review the matter de novo.

The parties may file objections to, or motions to adopt or modify, the Special Master’s scheduling plans, orders, reports, or recommendations no later than five (5) calendar days after the service of each, and the Court shall review those objections or motions, and any procedural, factual, or legal issues therein, de novo. Failure to timely object shall result in waiver of the objection.

The day after the 11th Circuit overruled her injunction on classified documents, on September 22, Cannon issued an order that everyone thought was just her acknowledging that the classified documents were no longer covered by the order (that’s not technically true, and I think she doesn’t believe it’s true even now, but it took the classified documents out of Dearie’s work plan). In taking out the reference to classified documents, it also took out this entire paragraph, including the bolded language about interim reports.

The Special Master and the parties shall prioritize, as a matter of timing, the documents marked as classified, and the Special Master shall submit interim reports and recommendations as appropriate. Upon receipt and resolution of any interim reports and recommendations, the Court will consider prompt adjustments to the Court’s orders as necessary. [my emphasis]

I raised it at the time, people poo pooed my concern (and scolded Dearie for raising it later). But this was the moment when Cannon told Dearie to fuck off, only without telling him she had done that.

Shortly after that, on day 7 after his appointment, Dearie submitted to the two sides his original plan. He gave them until September 27 to raise objections.

This Case Management Plan shall be filed on the docket and deemed served on each party today. The parties may file objections to, or motions to adopt or modify, the foregoing Case Management Plan by September 27, 2022. Failure to timely object shall result in waiver of the objection. See Appointing Order, ¶ 11; Fed. R. Civ. P. 53(f).1

1. To the extent the parties file objections with the Court as to this Case Management Plan, the deadlines set forth above shall remain in effect while such objections are pending.

Clearly, at that point, he believed he would have time to address any concerns himself. The work plan included his plan to use (and pay, as the only paid employee) retired Magistrate Judge James Orenstein to help with the review.

On September 23, DOJ informed Dearie that Trump still hadn’t contracted with a vendor to scan the documents, and asked for a one business day extension, but still with the expectation that Trump would arrange the contract (since he is paying). DOJ also asked him to tweak his order to make it clear the inventory would not include the potentially privileged documents. They noted that Trump still hadn’t provided his proposed protective order, which had been due September 20, which would have held up the document scanning anyway.

Later that day, Trusty filed a protective order.

Dearie issued an updated work order, with the same September 27 deadline for changes. It also still included his plan to hire Orenstein. I believe this is the work order Cannon took as operative on Thursday.

Also on September 23, Dearie issued a protective order that (the docket entry noted) had been approved by Cannon. It sided with Trump that he didn’t have to share the name of his reviewers, something that was made less urgent after the 11th Circuit had taken the classified documents out of the work plan.

On September 25, on Dearie’s original deadline for filing a work plan with Cannon (but before the date he provided for changes), Jim Trusty emailed Dearie his three objections: they didn’t want to affirmatively confirm the inventory, they didn’t want to distinguish between Executive Privilege that could and could not be shared with the Executive Branch, and they didn’t think they had to brief the appropriateness of filing a Rule 41(g) motion to Cannon rather than to Reinhart. This was not docketed and Judge Cannon is not listed as a recipient of this email. Chris Kise was on the signature block of this letter.

The next day, September 26, the second public deadline (after the protective order, which Trump missed), DOJ filed a revised and sworn affidavit. That was also the deadline for Trump to designate all the potentially privileged files he had had since September 16.

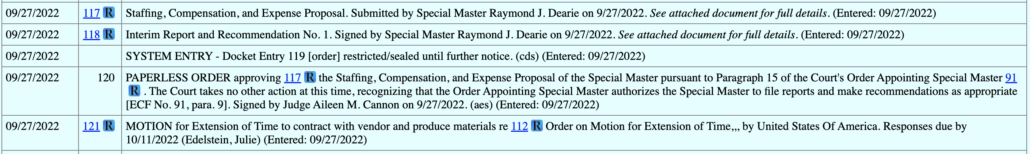

A bunch of things happened on September 27. I’ll treat them in the order they appear in the docket, which looks like this:

First, Dearie filed a staffing proposal to Cannon, noting that the window for the two sides to object to it had expired. This was the first moment that the staffing got separated from his work plan.

No party has submitted any comment to the foregoing proposal, and the time for such comment has lapsed. Accordingly, the undersigned respectfully submits the foregoing proposal to the Court for approval.

Then Dearie filed an interim report to Cannon. In it, he recommended Cannon add back in the language authorizing interim reports that she struck along with language about classified documents.

Interim Reports and Adjustments to Prior Orders. In the original Appointing Order, the Court directed that “the Special Master shall submit interim reports and recommendations as appropriate. Upon receipt and resolution of any interim reports and recommendations, the Court will consider prompt adjustments to the Court’s orders as necessary.” Appointing Order ¶ 6. However, the Court later struck that language as part of its order implementing an unrelated ruling by the Eleventh Circuit. As the language quoted above as to interim reports and adjustments to prior orders is consistent with the Eleventh Circuit’s ruling and the efficient administration of the Appointing Order as amended, the undersigned respectfully recommends that the Court issue an order reinstating that language.

His interim report clearly expected he’d get one more shot to resolve disputes. In it, he said the parties would have until October 2 to respond.

This Interim Report and Recommendation shall be filed on the docket and deemed served on each party today. The parties may file objections to, or motions to adopt or modify, the foregoing report and recommendation by October 2, 2022

Next, there’s a sealed (and still sealed) order.

Then Cannon approved Dearie’s staffing plan, but declined to replace the language in her original order that permitted interim reports.

The Court takes no other action at this time, recognizing that the Order Appointing Special Master authorizes the Special Master to file reports and make recommendations as appropriate.

It was not clear at the time, but this effectively told Dearie that his understanding of how things would work — that he could issue interim reports and only after that Cannon would intervene — had been changed in the wake of the 11th Circuit ruling on classified documents. Effectively, Cannon told Dearie on September 27 she had taken over the work plan on September 23. That’s why, I suspect, that she only cited his September 27 Interim Report in a footnote. She basically ignored everything he did after September 23.

After that, DOJ filed its request for another deadline extension, along with its objections to Trump’s objections received two days earlier.

On September 28, Trump for the first time raised timeline concerns in writing, also claiming that DOJ had told Trump there were 200,000 pages (as I’ve written here, that’s virtually impossible; I suspect it came from the work order DOJ provided to solicit the vendor). The letter was not signed by Kise, and raised a lot of bogus claims about privilege (and also seemed to indicate that Trump had already missed the privilege deadline). Along with those concerns about timing, Trump filed his complaints, which (at least based on the public record) was the first time Cannon would have seen the complaints; the docket exhibit is what she cited in her order.

Working under Dearie’s deadline, DOJ had four more days to respond to Trusty’s probably bogus claims of 200,000 documents and to rebut the privielge claims. Working off a five day deadline from Dearie’s submission of his amended work order on September 27, DOJ also had four more days. Working under Cannon’s original deadline — five days after Dearie’s original deadline of September 25 — they had two more days. Under Dearie’s September 23 order, the final deadline was September 27.

What Cannon appears to have done is with no formal notice of what the deadline was or even that ten plus five was no longer operative, treat Dearie’s September 23 filing as his final action in setting the plan, but along the way use her own five day deadline for complaints instead of the September 27 deadline Dearie gave, which is the only way Trump’s temporal complaint would be timely yet have her order not be days premature.

The next day, with no notice of any new deadline, Cannon issued her order throwing out most of Dearie’s plan. I’ve spent hours and days looking at this, and there’s no making sense of the deadlines. Certainly, this could not have happened if any of Dearie’s deadlines had been treated as valid.

DOJ took a look at what Cannon had done and moved the 11th Circuit to accelerate the review process. They cited a number of reasons for the change in schedule. They described that Cannon sua sponte extended the deadline on the review to December 16.

On September 29, subsequent to the parties’ submission of letters to Judge Dearie, the district court sua sponte issued an order extending the deadline for the special master’s review process to December 16 and making other modifications to the special master’s case management plan, including overruling the special master’s direction to Plaintiff to submit his designations on a rolling basis.

Depending on how you make sense of Cannon’s Calvinball deadlines, it was a sua sponte order, because Trump’s complaint about the deadlines (not to mention his complaints generally) came in after the deadline attached to the Dearie plan that Cannon seems to treat as his final official action.

I think what really happened is that Cannon fired Dearie without firing him in response to being told by the 11th Circuit she had abused her authority, ensuring not only that nothing he decides will receive any consideration, but also ensuring that he has almost no time to perform whatever review role he has been given.

Effectively, Judge Cannon has just punted the entire process out after the existing appeals schedule, at which point — she has made clear — she’ll make her own decisions what government property she’s going to claim Trump owns.

Timeline

September 15, 2022: Cannon opinion denying stay; Cannon’s order of appointment; Raymond Dearie declaration

September 16, 2022: DOJ motion for a stay

September 19, 2022: DOJ topics for initial Dearie conference; Trump topics for initial Dearie conference

September 20, 2022: Trump 11th Circuit response; DOJ 11th Circuit reply

September 21, 2022: 11th Circuit opinion granting stay

September 22, 2022: Cannon order removing documents marked as classified from Seized Materials covered by her order; Dearie proposed work plan

September 23, 2022: Protective order; amended case management plan; motion for extension of time

September 25, 2022: Trump objections to Dearie order (released on September 28)

September 26, 2022: Sworn affidavit with more detailed inventory; Julie Edelstein

September 27, 2022: Dearie interim report; Staffing proposal; Government motion for extension and to adopt case management plan

September 28, 2022: Trump objection that DOJ didn’t ask for enough additional time

September 29, 2022: Cannon order alters Dearie work plan

September 30, 2022: DOJ motion to accelerate 11th Circuit appeal

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)