Steve Bellovin, who for the reasons I laid out in this post, has impeccable credibility, has now weighed in on accused Vault 7 leaker Joshua Schulte’s bid for a mistrial. Bellovin is Schulte’s technical expert, and lost a bid last August to get direct forensic access to the workstation and servers at issue in his case.

The current bid for a mistrial is based on two complaints: first, DOJ withheld notice that the CIA had put Schulte’s buddy, Michael, on paid administrative leave last August until the day Michael testified. In addition, Schulte argued they had gotten inadequate forensic discovery to challenge the government’s case.

Ultimately, I think this bid — even with Bellovin’s renewed request — will likely not work. With regards to the forensics demand, this is really a complaint about a decision Judge Paul Crotty made under the Classified Information Procedures Act last summer, which Schulte renewed based off unpersuasive claims about the scope of one of the testimony of one of the government’s expert witness, Patrick Leedom, at trial. Schulte certainly can and no doubt will appeal Crotty’s decision, but the government claimed in its response that the defense didn’t make the more tailored requests for information that were permitted under Crotty’s order.

While the defendant has maintained his stubborn insistence on full forensic images, he has failed to actually make use of the information the Government provided, such as the data on the Standalone, to explain why the discovery produced by the Government was inadequate, or to take the Court up on its repeated invitation to the defense to make more narrow requests. In United States v. Hill, the court did order the Government to produce two mirror images of hard drives containing child pornography to the defense. See 322 F. Supp. 2d 1081, 1091 (C.D. Cal. 2004). Hill, however, does not involve the requested disclosure of an unprecedented and staggering amount of classified information without a showing that the information would be both “relevant and helpful,” as required by CIPA.2

With regards to the late notice about Michael’s paid leave, I think (though am not certain) that this is actually a Jencks issue, and I think (though am not certain) the government did comply with the letter of the law even if withholding the report was dickish and unnecessary.

In his declaration, Bellovin makes a frivolous point about Michael as an excuse to complain about both issues raised in the mistrial motion: that there was a common password to Confluence that Michael could have used to access the backup files from which Schulte allegedly stole the files.

The government makes a number of specific assertions that are misleading or simply false. For example, the government states that certain FBI reports “make clear that Michael never had Atlassian administrator privileges and thus did not have the ability to access or copy the Altabackups (from which the Vault 7 information was stolen).” Gov’t Opp. at 8. As a simple factual matter, this statement is untrue. The possession of “Atlassian administrator privileges” had nothing to do with the ability to access or copy the Altabackup files. Rather, what was needed was log-in access, i.e., a working user name and password, to the Confluence Virtual Machine (or “VM”). Michael certainly had such log-in access. As shown in Leedom Slide 60 (GX 1207-10 and GX 1207-11), which is described as “April 16, 2016 Confluence Backup— password and shadow files,” a user name called “confluence” is listed (Slide 60, GX 1207-11, third line from the bottom). The password for this user name was listed on a web page that was accessible to all OSB members, including Michael, and was used for many other log-ins throughout the organization. See GX 1202-5 (listing one commonly used password as “123ABCdef.”). This password was valid both before and after April 16, 2016. So if Michael had simply typed that password into the Confluence VM on April 20, 2016, along with the user name “confluence,” he would have had access to the Altabackup files from which the Vault 7 information was allegedly taken.

Not only has the defense known this for over a year, I even pointed to the availability of root passwords days after the initial leak in March 2017. So nothing about the late notice on Michael prevented Schulte from arguing this from the start. Moreover, this is something the government already addressed in their response.

Finally, the defense complains that he should have been able to examine the Confluence virtual machine to determine whether another user had “root” access, such as Michael. Again, the defendant’s argument fails. Initially, the defendant has been on notice since December 10, 2018 that Michael had “root” access to the ESXi Server, given that that fact was referenced in three different 302s produced to the defense at that time. Moreover, the defense has been provided with the available ESXi Server logs in discovery, such that he could have tried to determine whether any other user was logged in using the “root” password (there was not any such other user logged in during the reversion). Furthermore, to extent the defendant is complaining about the Confluence log files specifically, his assertion fails for two reasons. First, the Confluence log files of the activity on the Confluence virtual machine were deleted when the defendant reversed the reversion. Second, the Government produced to the defense the remaining Confluence application logs from April 7, 2016 through April 25, 2016 on June 14, 2019.

I remain sympathetic to Bellovin’s request in principle, but doubt that it will work legally in this instance. Plus, given Sabrina Shroff’s strategy on everything else, it seems they didn’t make the expanded requests earlier to leave open this opportunity to complain now.

What happens on appeal is a different issue though, one that goes to the heart of how CIPA gets applied in a computer hacking case like this. The government has, successfully, argued that the forensics of this case amount to classified information that must first qualify under the CIPA requirement that evidence is both relevant and helpful to the defense. I’m reasonably comfortable that the government has given Schulte enough forensics to test their theory of the case — that is, to test whether Schulte did revert backups on April 20, 2016 and access — and so presumably copy — the backup copy of the files published by WikiLeaks. But there are two questions they didn’t provide enough forensics to answer.

The first pertains to whether anyone else ever used the weak protections of these servers to do anything suspicious.

It’s clear that one prong of whatever defense Schulte will offer (and therefore what Bellovin will do in his testimony) is that CIA’s security was woefully inadequate, both in their physical space (Schulte was able to bring in thumb drives on at least two occasions and, the prosecution’s case suggests, even two hard drives) and digitally. Schulte’s lawyers have already brought out aspects of this on cross. What Bellovin won’t be able to do (aside from pointing to a time someone swapped the cables accessing the Internet, which resulted in a massive effort to clean up any data pollution of the CIA network) is point to any damage from real security incidents, aside from Schulte’s. And while that’s not necessary to rebut the government’s theory of the case, it is a part of arguing that Schulte was concerned about security himself (a claim that multiple witnesses have already credibly debunked) but also that the government was not making sufficient efforts to keep this National Defense Information secure, which is an element of the Espionage Act charges.

A far more interesting question pertains to the evidence against Schulte. Schulte is accused of stealing both the “Confluence” files — which are development notes — and “Stash” — which includes source code and user guides. The entirety of the Confluence files were posted on WikiLeaks on March 7, 2017, whereas a bunch of files from Stash were published, drip by drip, until November 2017.

The government has presented a compelling case that Schulte accessed a March 3, 2016 copy of Confluence and made a copy, based on existing logs of that back-up.

But it has not been able to do the same with Stash, I believe because the log files were deleted after the reversions that Schulte did on April 20, 2016, as elicited in cross-examination of “Dave,” the SysAdmin witness.

Q. That was confusing, you saying “yes,” me saying “okay.” Let’s talk about these missing Stash logs, okay? You said that you never would have in a security system or in a secure system lose logs, correct? A. Correct.

Q. And you were asked about missing logs, correct, missing logs from January 14 to April 21, correct? You remember that?

A. I’m sorry, I apologize, not really. But if it’s in the report, I may have talked about it.

Q. Let’s look at 3515-09. Page four. You were asked about missing logs from January 14 to April 21, 2016. Correct?

A. Is this — which exhibit is this? I apologize. I don’t have the right — do I have the right one?

The government has instead tracked file sizes and a copy date range to suggest that Schulte copied those files on that same date, here in testimony from expert witness Michael Berger.

Q. So what was your conclusion as to when the data, the range for the data?

A. For Stash we identified the range of data being from February 26, 2016, at 9:36 a.m., and March 4, 2016, at 9:45 a.m.

Q. Can you remind us, was there an identical hash for the marble file at March 1st?

A. Yes, there was.

Q. Was there a reason why you didn’t use March 1st here instead of February 26?

A. Yes.

Q. What’s that?

A. The reason is because that the files were identical, we didn’t want to assume that the data had to have come after March 1st. We took a more conservative approach and we slid our date back to being as possibly coming from after February 26 instead.

[snip]

Q. Let’s move on to the next. What does this reflect?

A. This reflects both the Stash and Confluence analysis. Looking at Stash, we can see that the data that was on WikiLeaks corresponds to the data from between February 26, at 9:36 a.m. and March 4, at 9:45 a.m. Looking at the Confluence data points, we’re able to get a smaller window that shows between March 2, 3:58 p.m. and March 3, at 6:47 a.m.

To some degree this doesn’t matter: leaking Confluence by itself would be a violation of the Espionage Act and so sufficient for guilty verdicts. But absent that evidence, the defense will be able to point to other questions about the Stash back-up made during the change in privileges on April 18, 2016, notably that the SysAdmin who changed privileges to the network on April 18, 2016, Dave, kept one copy on his desk and one copy on a hard drive he subsequently misplaced.

Q. You never told the FBI, did you, that you ever moved it to a locked compartment in your desk, correct?

A. Correct.

Q. And you also said that you actually couldn’t even recall if you had wiped the information about Stash off of that hard drive, correct?

A. Correct.

Q. And sitting here today, you have not a clue as to where that hard drive is, correct?

A. No, I don’t.

I don’t rule out Schulte using someone else’s privileges to delete the Stash logs (for example, he had and used the credentials of “Rufus,” a guy who was supposed to work in SysAdmin but moved on after a short period, in his April 20 hack). But the government hasn’t shown that, perhaps because doing so would implicate one of their key witnesses.

Given the cross of Patrick Leedom, I think it quite likely Schulte’s team knows what happened and plans to unveil it to maximal advantage during their defense.

Q. And according to you and the government, shortly afterward, during this reversion period, the theory is that he also accessed the Stash backup file, correct?

A. That would be correct.

Bellovin may have a very good idea of where such evidence would be — I’m particularly intrigued by this request, because the government doesn’t appear to understand why Bellovin asked for it — and may even know, via Schulte (who spent a lot of time on obfuscation) that it would look exculpatory (but that’s based on the government’s response, not any understanding of what this might show).

The defendant argues that he could not test the vulnerability of the “DS00 file system,” without access to the mirror image of the NetApp Server. The defendant does not explain why this forensic artifact would demonstrate any vulnerabilities or how any part of Mr. Leedom’s testimony-which did not reference the file system-implicated this assertion. Therefore, the defendant has not established that a mistrial is required based on this claim.

Then there’s a far more interesting question. As of the date of completion of a WikiLeaks Task Force Report on October 17, 2017, as brought in via the testimony of Sean Roche, the CIA had only moderate confidence that WikiLeaks hadn’t obtained the “gold repository” of finished exploits.

Q. Right. All you know is, in 2017, WikiLeaks published it, correct?

A. That’s correct.

Q. And did you by any chance learn that even after 2017 publication, the CIA still did not know whether or not WikiLeaks had the information from the gold repository?

MR. DENTON: Objection.

THE COURT: Overruled.

A. Could you repeat that, please, ma’am.

Q. Sure. Is it fair to say, sir, that the CIA slash you still don’t know if WikiLeaks has the gold repository?

THE COURT: Rebecca, could you read the question back, please. (The record was read)

A. I believe that represents the last conversation I had on what is called the gold repository.

Q. So I’m correct.

A. Yes.

Q. CIA still doesn’t know?

A. I don’t know that, ma’am. I don’t work there anymore.

Q. You know what the WikiLeaks task force report is?

A. Yes, I do.

Q. Could you pull that up for this gentleman, please. Are you happier with a paper copy or the screen?

A. We can do this.

Q. Could we just go to page 45. Could you just focus on the actual text. You see that line, “However we now assess with moderate confidence”?

A. Yes.

Q. Right. “Moderate confidence that WikiLeaks does not possess the gold folder,” correct?

A. Correct.

This is clearly testimony prosecutor David Denton did not want to come in.

That moderate confidence judgment appears to be based on Leedom’s analysis of what privileges Schulte himself had.

Q. You see there a folder at the bottom, “source code and binary gold copies”?

A. Yes.

Q. What are those?

A. These are the delivered completed tools from the work at EDG.

[snip]

Q: Would the defendant have been able to copy the gold source folders?

A: No, he would not have had access to it with his DevLAN account.

But given Schulte’s own behavior, it’s not clear this analysis can rule out the possibility Schulte took the gold repository.

One of the last events in Schulte’s never-ending escalation of grievances came when he sent an email on June 28, 2016 to Meroe Park, the CIA Executive Director (the #3 ranking official at CIA), Andrew Hallmen, who was then the Director of the Directorate of Digital Innovation (and just got ousted as Deputy Director of National Intelligence in the purge of ODNI last week), and Sean Roche, the Deputy Director of DDI. This came in the wake of Schulte first obtaining privileges to his old project, Brutal Kangaroo, and then booting all the other developers off it. In response to the email, as laid in Roche’s testimony, Roche first responded immediately via email and then had a meeting with Schulte on June 30, 2016. In the meeting with the senior most official Schulte met with, he insinuated he still might get his administrator privileges back.

Q. What did you mean when you say you asked him about permissions?

A. On the system that he was working on, an agency network, his — he had — his permissions had been changed, and when his management explained to him, he went back in and changed his permissions back to get access again, and they had issued a letter of warning to him explaining how serious that was and that that behavior is not acceptable.

Q. Why was that something you discussed with him?

A. Because of how serious the nature of that is. Activity on any system that holds agency data, agency tools, things that we call sources and methods, is — is — it is very, very important that we not have a doubt about what people have access to and maintain the integrity and the protection of that information.

Q. What did you discuss with him about his permission changes?

A. I said to him something to the effect of in the post-Edward Snowden era, you don’t do something like that. That’s going to draw attention that you certainly don’t want. It’s really serious, and you cannot be taking that kind of action.

Q. And how did he respond?

A. He talked a little bit about the project that he had been working on and some new work that he had been given, and he was not pleased with it. But at one point, he stopped and he looked at me and said, You know, I could get back on it if I wanted to, something to — that’s not — I won’t say that’s the exact quote, but it’s pretty darn close.

Q. Now, when he said that, did you understand him to be raising a security concern about the network?

A. No. What I, what I realized — it was a striking comment because, to me, it illustrated that after everything that had happened, all the warnings, all of this formal process, that he was determined to undermine the controls on the network.

Brutal Kangaroo is a USB-based tool to exfiltrate from air-gapped machines. Schulte unsuccessfully attempted to delete the copy of Brutal Kangaroo he had worked on at home on April 28, 2016. But he regained access at CIA in June. He also had worked on serious obfuscation tools.

Given the state of the CIA networks, it’s not impossible that Schulte made good on that threat using tools built by the CIA to make it difficult for the CIA to discover if it happened.

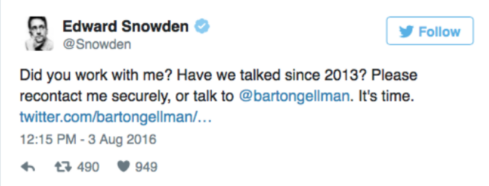

Not long after, in August 2016, according to warrant affidavits the substance of which have not yet been entered into evidence at the trial (they’re likely to come in early this week via an FBI Agent laying out the evidence of the rest of the charges, including obstruction and lies in FBI interviews as well as the MCC charges), Schulte started getting really interested in WikiLeaks and Shadow Brokers and Edward Snowden.

Schulte stuck around months after he allegedly first stole data from the CIA, and he threatened a very senior official that he might regain access that would allow him to do so again.

Having access to logs that might suggest that had or had not happened wouldn’t help Bellovin refute the case against him. But it might hide details of still worse compromise that the CIA would like to keep quiet.

I think Schulte can — and will attempt to, on appeal — argue that the forensics behind a hack are a different kind of classified evidence than intelligence itself (that is, information about what the intelligence community knows), both because it is neutral data about potential compromise and because you can’t just substitute a name like you can for other intelligence. In this case, it goes to the heart of a dispute about whether the CIA was really doing what it needed to do to keep these files safe. The evidence doesn’t suggest that Schulte gave a damn about all that; on the contrary, he clearly exploited it. But it’s evidence he can make a claim to need to rebut the Espionage Act charges against him.

But I also wonder whether the CIA refused to grant Bellovin access in this case (who, as I’ve noted, has been trusted by the government in other programmatic ways, including as the technical advisor to PCLOB) not because of any exculpatory evidence they were hiding, but because of inculpatory evidence.

Update: Yikes. The government submitted a scathing “correction” of Bellovin’s declaration.

The Bellovin Affidavit asserts that the log files from the ESXi server produced by the Government in discovery were “demonstrably damaged” as a “result of prior forensic examination.” However, on or about June 14, 2019, in response to the defense’s request, the Government produced unmodified copies in their original format of both log files and unallocated space from the ESXi server.

The Bellovin Affidavit also asserts that the Government only provided “heavily redacted” versions of the Confluence databases, and not “a full copy of the SQL file.” On or about November 5, 2019, the Government provided defense counsel and the defendant’s expert access to a standalone computer at the CCI Office containing, among other things, (1) complete, unredacted copies of the March 2 and 3, 2016 Confluence databases (i.e., a “full copy of the SQL file”) and all of the Confluence data points used by Michael Berger, one of the Government’s expert witnesses, to conduct his timing analysis; (2) complete, unredacted copies of the Stash repositories for the tools for which source code had been released by WikiLeaks; (3) complete, unredacted copies of all Stash documentation released by WikiLeaks; and (4) all commit logs for all projects released by WikiLeaks, redacting only usernames. The Government understands that Dr. Bellovin examined the standalone computer at the CCI Office in December 2019.

It also suggests that Bellovin’s assertion that the Confluence root password would give Michael access to the backups is wrong, but won’t explain why until Bellovin takes the stand.

Finally, the Government does not address Dr. Bellovin’s incorrect assertions regarding Michael’s access to the Altabackups in this letter. Should Dr. Bellovin testify, the Government will cross-examine him regarding, among others, those substantive matters (using information that has already been produced to the defense in discovery). The Government notes, however, that, to assert incorrectly that Michael had access to the Altabackups, Dr. Bellovin relies on information that has been available to him since well before trial, such as the screenshot taken by Michael on April 20, 2016, which was produced by the Government to the defense in December 2018, and data for the Confluence virtual machine, which was produced by the Government to the defense by July 2019, and not on any information disclosed by the Government regarding Michael’s administrative leave status during trial.

Schulte may be yanking Bellovin’s chain on this claim.