There’s something about the second Josh Schulte trial I’ve always meant to go back and lay out. It pertains to what I think of as Schulte’s “Guccifer Gotcha.”

Throughout the trial, Schulte, who was representing himself, often got caught up in proving — right there in the courtroom — that he was the smartest guy in the room. That often (particularly with prosecutors’ technical expert and a former supervisor) led Schulte to get entirely distracted from proving his innocence. He focused on proving he was smart, rather than not guilty.

A particularly revealing instance came with Richard Evanchec who, as a member of New York Field Office’s Counterintelligence Squad 6 that focused on insider threats, was one of the lead FBI agents on the Schulte investigation.

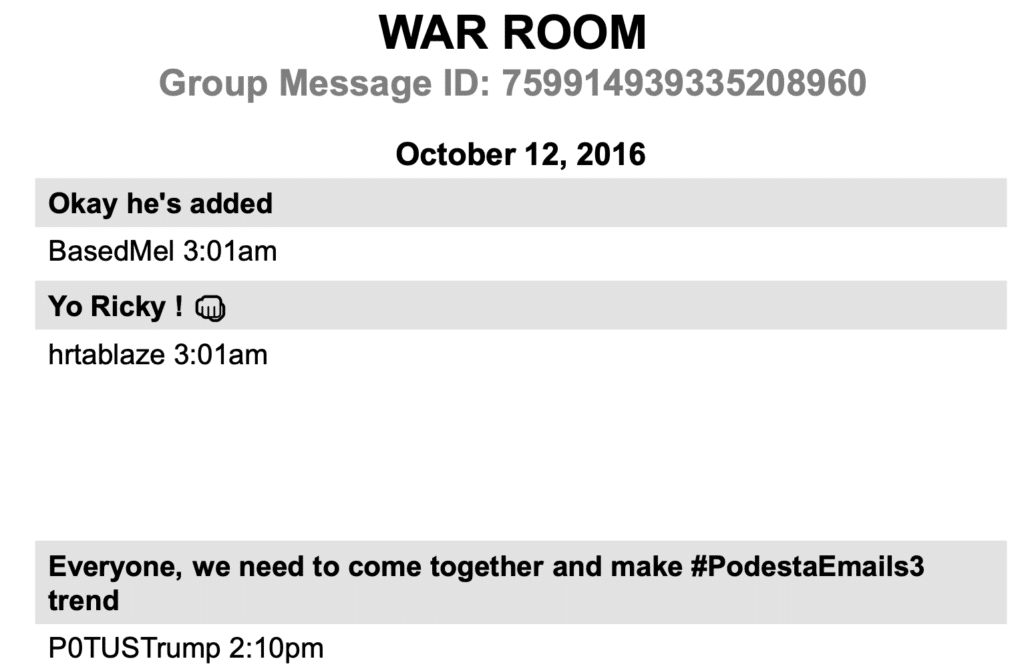

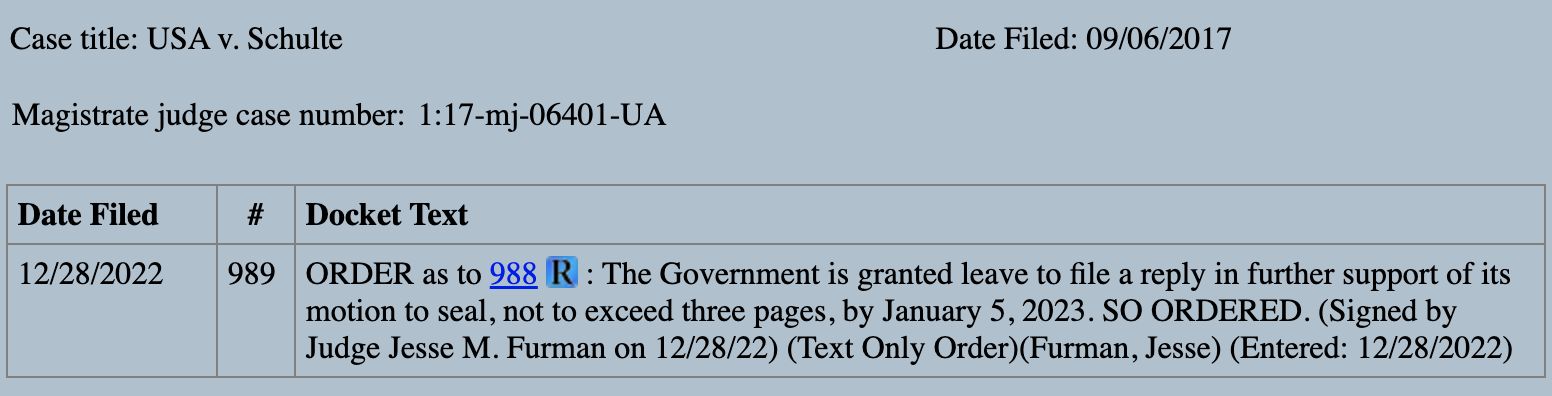

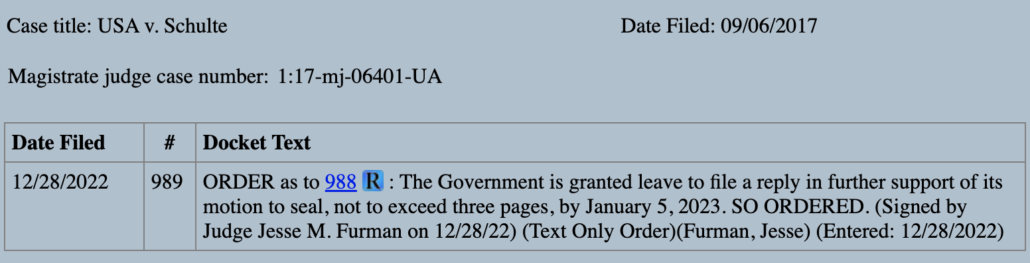

On direct, Evanchec had described how before, August 2016, Schulte had only done three searches — ever — on WikiLeaks, but he did 39 searches between August 2016 and January 2017, when WikiLeaks announced Vault 7. (This exhibit is from Schulte’s first, 2020 trial; because the exchange below describes the August 16 search as the first one, I believe the one from his 2020 trial may not have included the Snowden search.)

Schulte started his cross on this topic by asserting that Evanchec had “made [a] grave mistake” in calculating Schulte’s Google searches.

[Reminder: these transcripts were paid for by Wau Holland foundation, which has close ties to WikiLeaks.]

Q. Additionally, sir, did you realize that you made the grave mistake in calculating the Google searches during this time period?

A. I don’t.

Q. You don’t recall that.

A. No.

[snip]

Q. Did you not realize, sir, that 80 percent of the searches you claim that I conducted for WikiLeaks were not actually searches at all?

A. I don’t know that, sir, again.

Q. Sir, are you familiar with the service Google offers called Google News?

A. I am not. I don’t use Google regularly or gmail regularly so I don’t know what that is.

Schulte then walked Evanchec through how a Google News search and a related page visit search show up differently in the logs, demonstrating the concept with some activity from early morning UTC time on August 17, 2016 on Schulte’s Google account.

Q. Did you know that Google makes a special log in its search history when you are using Google News?

A. I don’t. I am not aware of that.

[snip]

Q. OK. Entry no. 12954.

A. Your question, sir?

Q. Can you read just the date that this search is conducted?

A. Appears to be August 17 of 2016 at 2:45:07 UTC.

Q. Can you read what the search is?

A. Searched for pgoapi.exceptions.notloggedinexception. Then there is: (https://www.Google.com/?Q=pgoapi.exceptions.notloggedinexception).

Q. OK. And then the search after it, Google has it, produces it in the opposite direction so the one after that. Can you read that?

A. You are referring to line 12953?

Q. Yes. I’m sorry. Thank you.

A. Tease [sic] OK. Again August 17, 2016, 2:35:27 https://www.google.com/search?Q=WikiLeaks&TBM=NWS).

Schulte then got Evanchec to admit that the FBI agent didn’t consult with any FBI experts on Google before he did his chart of Google searches.

Q. So you basically, just as a novice, opened up this document and just based on no experience, you just picked out lines; correct?

A. No.

Q. No. You did more?

A. Yes. I queried for every time this history set searched for and then included the search terms. That’s what I culminated in my summary.

Q. OK, but you didn’t run that by any of the technical experts at the FBI, did you?

A. Not that I recall.

Q. And you said you didn’t reach out to Google or anyone with expertise, correct?

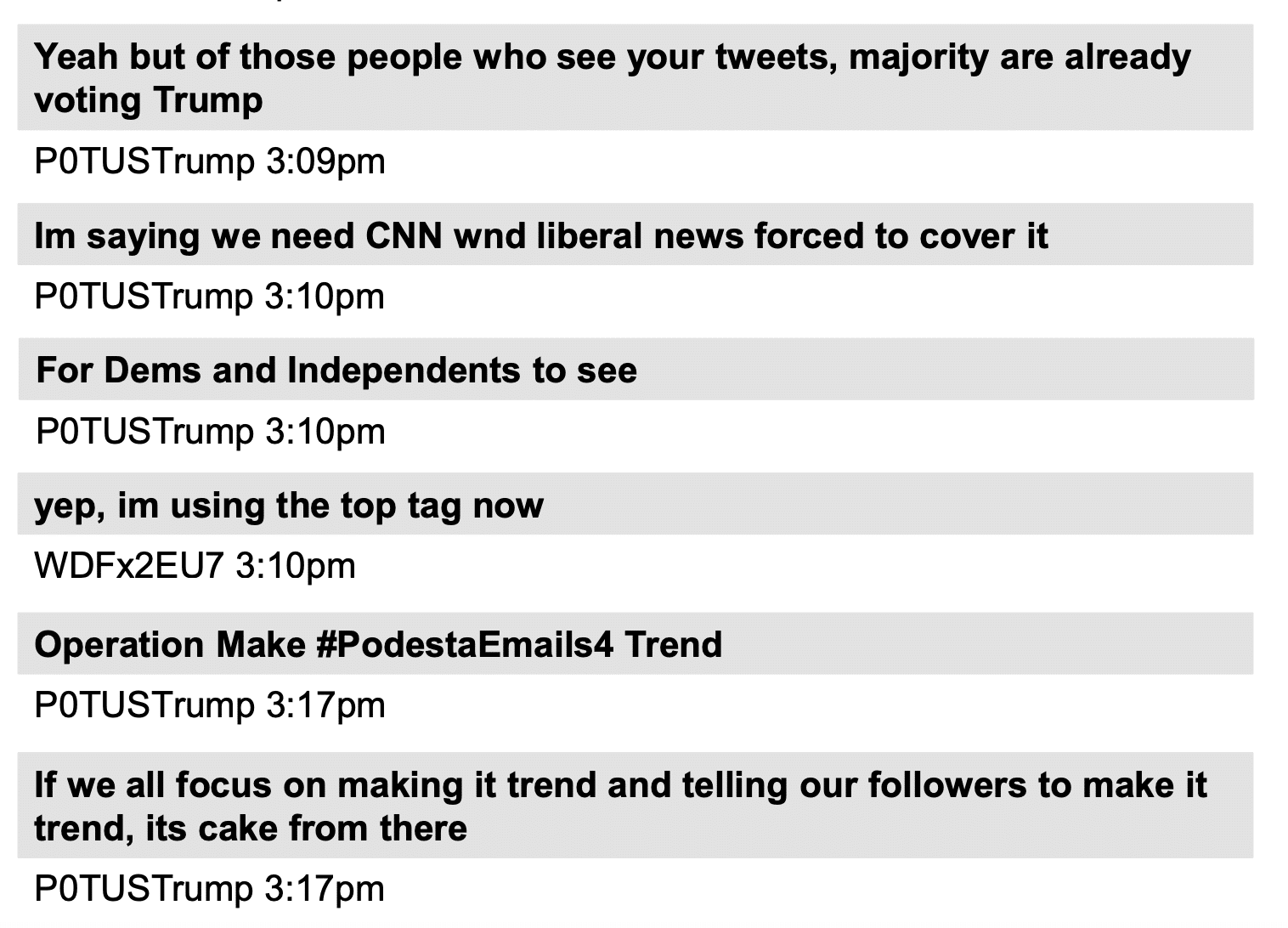

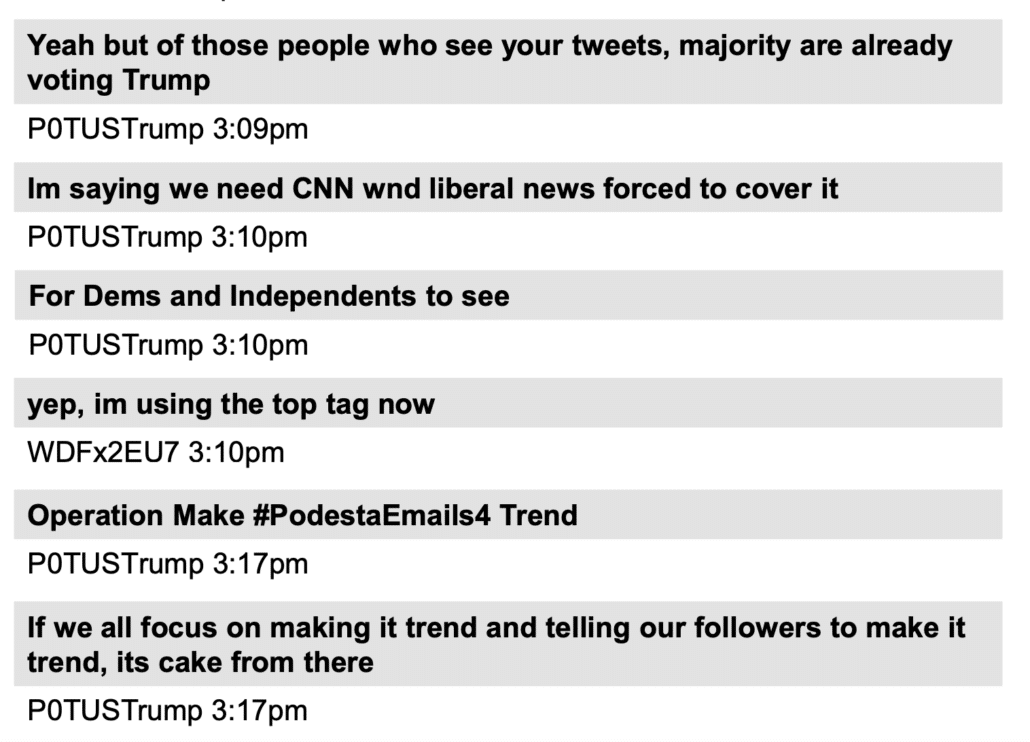

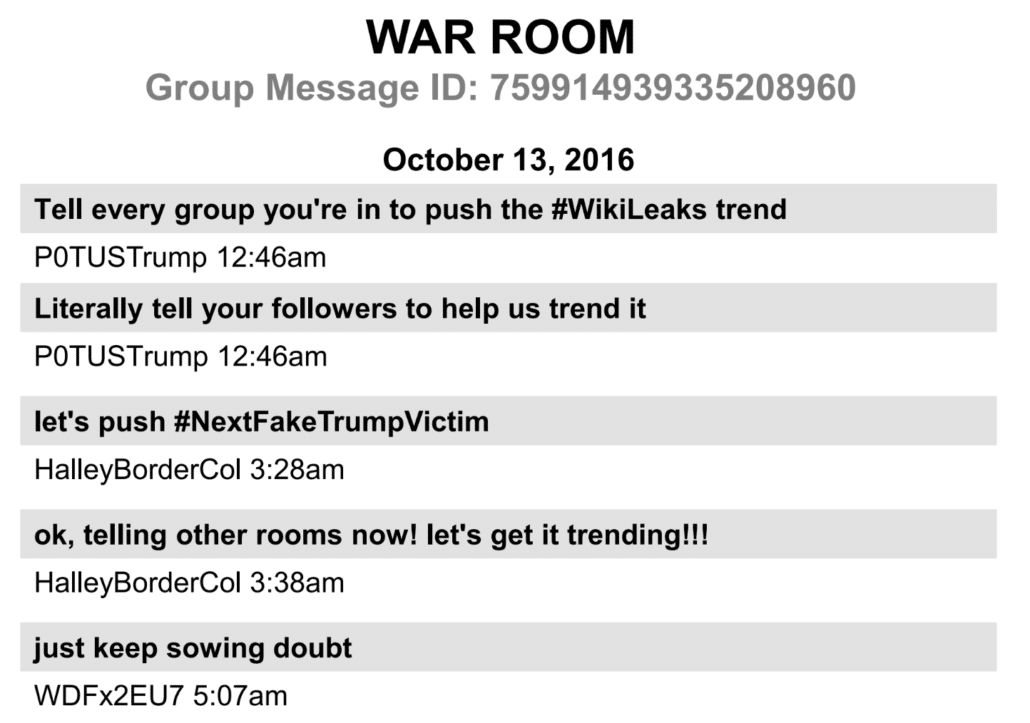

In his close, Schulte claimed that the exchange showed that all the Google searches he did between August 2016 and January 2017 were based off a Google news alert, and what drove the number of searches was the degree to which WikiLeaks was in the news because of the DNC hack-and-leak.

Mr. Lockard then brings up the Google searches for WikiLeaks, but of course, as Agent Evanchec testified, there were multiple news events that occurred in the summer of 2016. WikiLeaks dumped the Clinton emails. Really? Come on. Everyone was reading that news — Guccifer 2.0. The Shadow brokers released data, and even WikiLeaks claimed to have that code.

No doubt Schulte did demonstrate clearly to Evanchec that he didn’t did look closely at the logs of these searches and that he — Schulte — knew more about Google searches than one of the agents who had led the investigation into him did.

He was the smartest guy in the room.

But in the particular search in question — one that would have been before midnight on August 16, 2016 on the East Coast — what Schulte appears to have shown is that among all the Google news alerts reporting on a flood of news about WikiLeaks, one of the only alerts that he clicked through was one reporting WikiLeaks’ claim to have a tie to ShadowBrokers.

WikiLeaks on Monday announced plans to release a collection of “cyber weapons” purportedly used by the National Security Agency following claims that hackers have breached a division of the NSA said to deal in electronic espionage.

“We had already obtained the archive of NSA cyber weapons released earlier today and will release our own pristine copy in due course,” WikiLeaks said through its official Twitter account Monday.

Individuals calling themselves the “Shadow Broker” claimed earlier in the week to have successfully compromised Equation Group — allegedly a hacking arm of the NSA — and offered to publicly release the pilfered contents in exchange for millions of dollars in bitcoins.

At a threshold level, Schulte’s gotcha doesn’t show what he claimed it did. It showed that among the flood of news about WikiLeaks — almost all focused on the DNC hack-and-leak — he clicked through on stories about an upcoming code release. “Everyone was reading that news — Guccifer 2.0,” Schulte said. But he wasn’t. He clicked on one Guccifer story. He was sifting past the Guccifer news and reading other stuff. Schulte caught Evanchec misreading the Google logs, but then went on to misrepresent the significance of what they showed, which is that amid a flood of news about the DNC hack-and-leak, he was mostly interested in other stuff.

More importantly, once you realize that Evanchec hadn’t looked closely at the logs of these Google searches, something about his first demonstrative — showing just these three searches before August 2016 — becomes evident.

July 29, 2010: Searched for “WikiLeaks”

- Visited Wikileaks.org webiste [sic]

July 30, 2010: Searched for “WikiLeaks ‘Bastards’”

- Visited website titled “WikiLeaks Plans to Post CIA Chiefs Hacked Emails” on The Hill

July 6, 2016: Searched for “WikiLeaks Clinton Emails”

- Visited website titled “WikiLeaks Dismantling of DNC Is Clear Attack By Putin on Clinton” on The Observer

For at least two of these searches, the date in Evanchec’s demonstrative cannot reflect the actual date of the search.

The story, “WikiLeaks Dismantling of DNC Is Clear Attack By Putin on Clinton” — one of the first ones concluding from the DNC hack that Putin was involved — was not posted until July 25, 2016, yet Evanchec’s demonstrative says the search happened weeks earlier.

The story, “WikiLeaks Plans to Post CIA Chiefs Hacked Emails,” describing the Crackas With Attitude hacks of top intelligence community figures in advance of the 2016 operation, dates to October 21, 2015. Evanchec described Google records that say the search happened five years before the article was posted.

Neither of those searches could possibly have been done on the date in Evanchec’s demonstrative, which Schulte — in spite of his obsession with being the smartest guy in the room — undoubtedly knew but didn’t point out at trial.

Schulte got his gotcha. It didn’t help him secure acquittal (or even another hung jury). And it got me, at least, to look more closely at what it proves, which is that at least two of the manual searches Schulte did, searches that sought out very select stories, seemed to obscure the date of the search.

As I said, I’ve been meaning to post this ever since it happened at trial.

I’m revisiting it, though, because of something remarkable about Charles McGonigal’s sentencing memo. Unsurprisingly, his attorney, former Bill Barr flunkie Seth DuCharme, lays out a bunch of the important FBI investigations that McGonigal was a part of over his 22-year FBI career to describe what service he has done for US security: TWA Flight 800, the 1997 investigation into attempted subway bombers Gazi Ibrahim Abu Mezer and Lafi Khalil, the investigation into the 1998 bombings of US embassies in Africa, the 9/11 attack, the 2002 abduction of a Wooster County, OH girl, the Sandy Berger investigation, the RICO investigation of Huawei Technologies Co.

The government, in their own sentencing memo, includes a footnote suggesting that McGonigal is fluffing his role in at least one of these investigations.

The law enforcement and counterintelligence agents who reviewed McGonigal’s cited exploits noted that he often claims credit for operations in which his personal involvement was less significant than the operation itself. For example, in both his classified and unclassified submissions, McGonigal may describe a significant investigation where he—along with many other officials—was simply somewhere in a lengthy chain of command. (See PSR ¶ 82). Thus, to the extent this Court is inclined to parse McGonigal’s career achievements, the Government respectfully submits that it should limit its analysis to the specific actions that McGonigal personally took. See United States v. Canova, 412 F.3d 331, 358-59 (2d Cir. 2005) (Guidelines departure for exceptional public service warranted where defendant served as volunteer firefighter “sustaining injuries in the line of duty three times,” “entering a burning building to rescue a threeyear old,” “participated in the successful delivery of three babies,” and administered CPR to persons in distress both while volunteering as a firefighter and as a civilian).

One example where McGonigal claimed credit for being in a lengthy chain of commend must be the Huawei investigation, one that Seth DuCharme would also have worked on in the period when he and McGonigal overlapped in NY, from 2016 until 2018. The 2020 press release that DuCharme links to about that investigation, from over a year after McGonigal retired, includes two paragraphs of recognition, including units far afield from counterintelligence.

But one investigation included in McGonigal’s sentencing memo where he did have more involvement is the original WikiLeaks Task Force.

Mr. McGonigal later led the FBI’s WikiLeaks Task Force investigating the release of over 200,000 classified documents to the WikiLeaks website—the largest in U.S. history—ultimately resulting in the 20-count conviction of Chelsea Manning for espionage and related charges.

Charles McGonigal did have a significant role in the first criminal investigation of WikiLeaks, one conducted five years before his retirement.

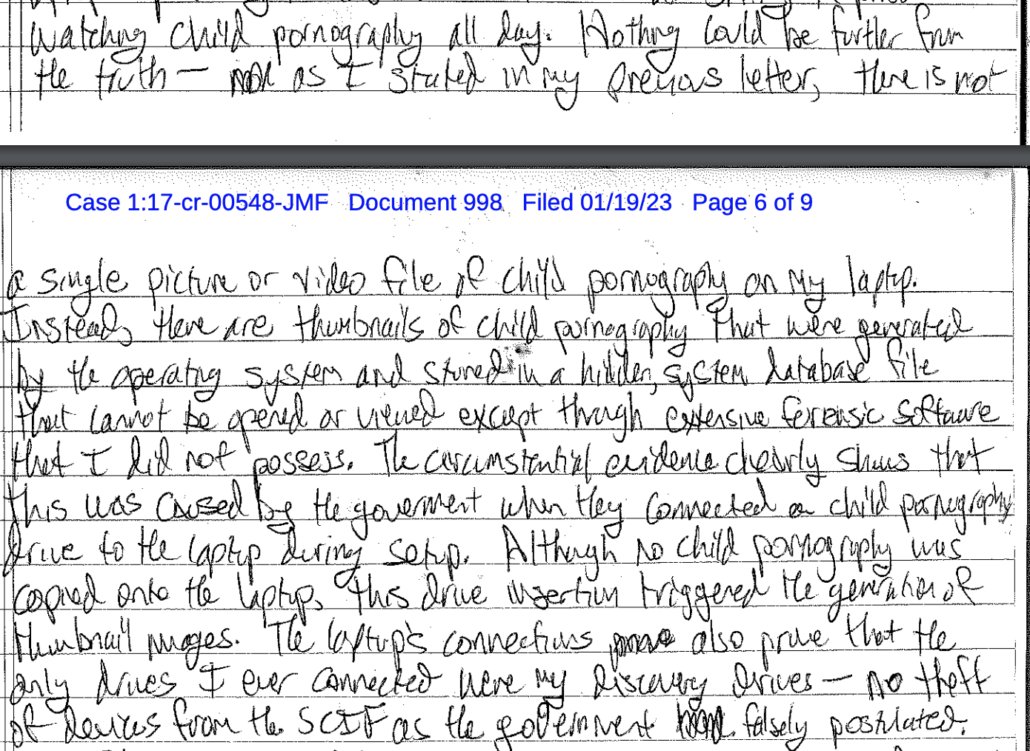

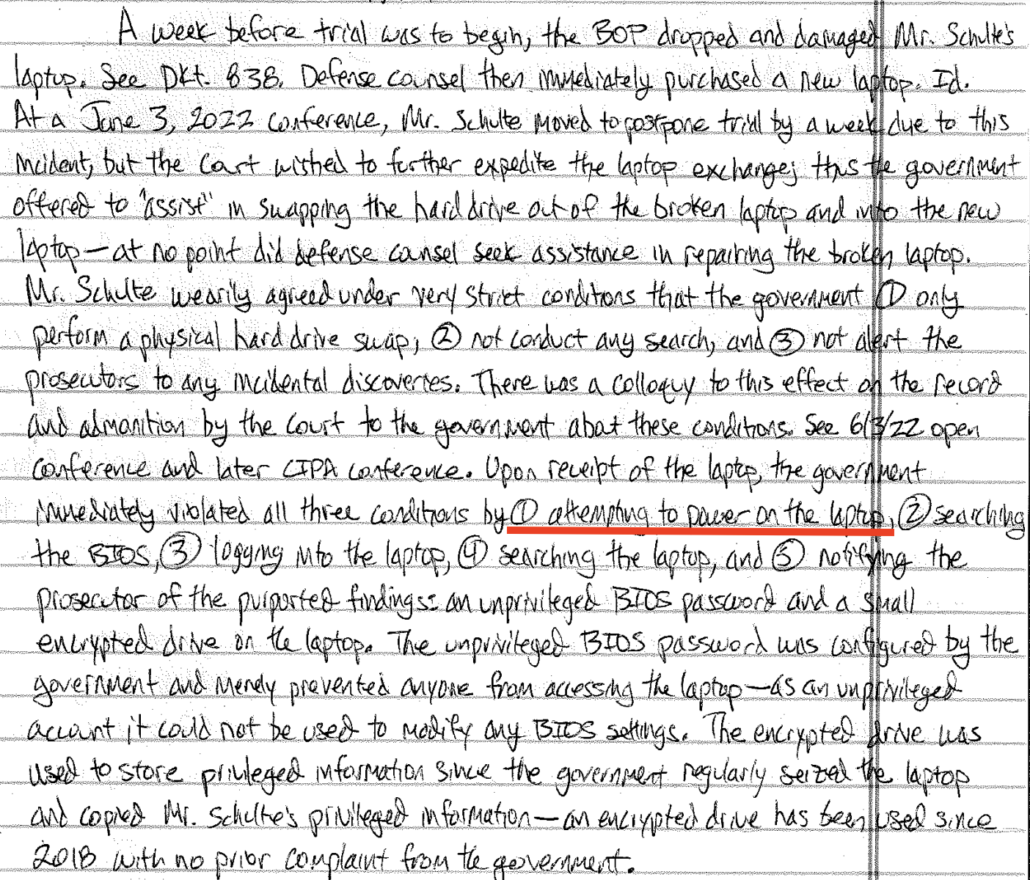

And that’s why it’s weird that McGonigal doesn’t describe that, in the 18 months before he retired, including in the period between May 2017, when he received a report describing Oleg Deripaska’s ties to GRU, and the period, starting in March 2018, when McGonigal first started interacting with Deripaska’s deputy, Yevgeny Fokin, whom McGonigal allegedly identified as a Russian intelligence officer and claimed to want to recruit, a unit McGonigal supervised solved a WikiLeaks compromise even more damaging and complex than Chelsea Manning’s had been four years before.

Charles McGonigal doesn’t claim credit for the arrest of Josh Schulte and charges filed, over two years after the compromise, for the Vault 7 attack, something in which his team had a more central role than in the Huawei case, something that was every bit as important to national security.

By that point, WikiLeaks had ties to Russia not just through Israel Shamir but also — at least through a shared lawyer — with Oleg Deripaska. That shared lawyer almost negotiated immunity for Assange in exchange for holding off on the Vault 7 leaks.

Now, I’m not at all suggesting that McGonigal was responsible for that fucked up Google analysis, which Schulte would mock five years later. There would have been several levels of management between McGonigal and that analysis. Evanchec simply didn’t look closely enough at the Google metadata, and so didn’t see that those searches were even more interesting than he understood.

But what McGonigal would have known, when he was meeting Deripaska personally in 2019, was that the FBI hadn’t discovered that Schulte had somehow obscured when he did his search on WikiLeaks’ role in embarrassing CIA Director John Brennan and National Security Director James Clapper in 2015, in advance of the 2016 election attack, that he had likewise obscured the date when he searched on Putin’s role in the DNC hack-and-leak. The FBI didn’t even know that in 2022, by the second trial.

McGonigal may also have known what someone associated with WikiLeaks told me, in 2019, that the FBI had learned about Schulte: that he had somehow attempted to reach out to Russia.

To be clear: None of this is charged. There’s no evidence that McGonigal shared details he learned as NYFO’s counterintelligence head, about the WikiLeaks investigation, to say nothing about NYFO’s investigation of oligarchs like Deripaska. McGonigal’s case has been treated as a public corruption case, not an espionage case. So it may be that SDNY has confidence that McGonigal didn’t do anything like that.

But this risk — the possibility that McGonigal could have shared investigative information with Deripaska — doesn’t show up in SDNY’s sentencing memo. SDNY makes no mention of how obscene it is that DuCharme wants his client to get probation when any witnesses implicated in the investigations McGonigal oversaw would never know whether he had shared that information with Deripaska.

That includes me: As I have written, in August 2018, the month before McGonigal retired, someone using one of the ProtonMail accounts Schulte and his cellmate used reached out to me. I have no idea why they did that. But I’d love to know. I’d also love to know whether McGonigal learned of it and shared it.

It makes sense that McGonigal doesn’t emphasize what SDNY did on their own sentencing memo: That McGonigal went from supervising investigations into Deripaska to working for him, allegedly knowing full well he had ties to Russian intelligence. But the tie between WikiLeaks and Deripaska is more obscure, and so he could have bragged that twice in his career he led substantial investigations into WikiLeaks. Schulte’s third trial, for Child Sexual Abuse Material, even happened after Judge Jennifer Rearden became a judge in October 2022.

McGonigal could have bragged that twice in his career, in 2014 and in 2018, teams he oversaw solved critical WikiLeaks compromises. He only claimed credit for the first of those.

Update: Corrected Fokin’s first name.