In addition to declassifying the analogies to the Wizard of Oz Janice Rogers Brown made in her opinion on Adnan Farhan Abd Al Latif’s habeas petition, the government also declassified passages from the Latif cert petition.

Newly declassified passages make it clear the report in question is TD-314/00684-02

Among the passages newly declassified is this paragraph from the document at the heart of the Latif case.

History: Subject met Ibrahim Al-((‘Alawi)) from Ibb during 2000. ‘Alawai talked about jihad and Afghanistan and convinced subject that he should travel to Afghanistan. Subject did not know if ‘Alawi had actually participated in any jihad activity himself. Subject departed home in early August 2001, travelled by car to San’a, then by airplane to Karachi. He took a taxi to Quetta, then crossed into Qandahar where he went to the grand mosque, where he met ‘Alawi. He went to ‘Alawi’s house, where he remained for three days. ‘Alawi owned a taxi in Qandahar, and had his family with· him. ‘Alawi took him to the Taliban, who gave him weapons training and put him on the front line facing the Northern Alliance north of Kabul. He remained there, under the command of Afghan leader ((Abu Fazl)), until Taliban troops retreated and Kabul fell. Subject claimed he saw a lot of people killed during the bombings, but never fired a shot. He went to Jalalabad, then crossed into Pakistan with fleeing Arabs, guided by an Afghan named Taqi ((AIlah)). While he was with the Taliban, he encountered ((Abu Hudayfa)) the Kuwaiti, ((Abu Hafs)) the Saudi, and ((Abu Bakr)) from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) or Bahrain.

By comparing that paragraph with the parts of Latif’s Gitmo file sourced to TD-314/00684-02, we can be virtually certain that the document at issue is, in fact, TD-314/00684-02. (Each sentence below is followed by the page on which it appears in Latif’s Gitmo file.)

Detainee admitted Ibrahim Aliwee convinced detainee to travel to Afghanistan for jihad and admitted staying at Abu Khulud’s residence for a short period in Kandahar. (5) Detainee admitted receiving weapons training from the Taliban and then fighting in support of the Taliban on the front lines. Detainee remained there until the Taliban retreated and Kabul fell to the Northern Alliance. (6)

Detainee admitted after training he was sent to the front lines north of Kabul. Detainee remained there until the Taliban retreated and Kabul fell to the Northern Alliance. (6-7) Detainee claimed he saw a lot of people killed during the bombings, but never fired a shot. (3) Detainee then traveled to Jalalabad, AF, and crossed into Pakistan with fleeing Arabs, guided by Taqi Allah. (3) While detainee was with the Taliban, he encountered Abu Hudayfa the Kuwaiti; Abu Hafs the Saudi, and Abu Bakr from the United Arab Emirates or Bahrain. (3)

The last two sentences, in particular, make the match particularly clear, given that those details were newly added to Latif’s Gitmo file from TD-314/00684-02 in 2008. Also note, the only major claim in the paragraph above not clearly sourced to TD-314/00684-02 in Latif’s file–“He remained there, under the command of Afghan leader ((Abu Fazl)), until Taliban troops retreated and Kabul fell”–appears this way in Latif’s Gitmo file without clear attribution but in a paragraph otherwise sourced to TD-314/00684-02:

He remained in Kabul under the command of Afghan leader Abu Fazl, until Taliban troops retreated and Kabul fell.

All of this makes it virtually certain that the report in question is TD-314/00684-02.

Newly declassified passages also show that the interrogation in question happened while Latif was in Pakistani custody

We can also show with a high degree of certainty that the interrogation in question happened while Latif was still in Pakistani custody.

This sentence, from page 10 of the cert petition, makes it fairly clear that the interrogation, if not the document itself, dates to December 2001 (the CIA file has a 2002 date, so it probably wasn’t drafted until the following month).

The government’s case was “primarily based” on a single document, created [~1 word redacted] in late December 2001 [3-4 words redacted].

But there’s an even more interesting reference to the timing of the interrogation in the new version of Henry Kennedy’s opinion. After a long still-redacted paragraph on page 6 introducing TD-314/00684-02, there’s a brief reference to “in late December 2001,” further redaction, the footnote 5, and then a new sentence introducing further, more detailed description of TD-314/00684-02.

Here’s what we see in the footnote:

That is, not much. But enough to see that the contents are derived from something that appears to use “late December 2001” as a date rather than a specific date itself. (That is, Kennedy uses quotation marks for the date, to indicate that the document he looked at included not a specific date, but this more general one.)

According to Latif’s Gitmo file and TD-314/00845-02 (a document that appears to have primarily served to record the transfer of custody from Pakistani to US custody), Latif was transferred on December 30, 2001. According to his intake form (see PDF 32-34), he was transferred on December 31, 2001.

Unless the interrogation happened on December 30, as the Pakistanis were transferring Latif to US custody, then it happened while he was still formally in Pakistani custody.

Only Yemenis are known to remain at Gitmo based on this document

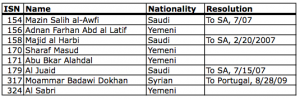

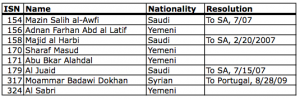

As I’ve explained before, TD-314/00684-02 was not a report detailing just Latif’s intake in Pakistan. The Gitmo Files of at least 7 other men cite TD-314/00684-02. As this table shows–and I describe in more detail below–the Saudis and the Syrian held, at least in part, based on the interrogation reported in TD-314/00684-02 have all been transferred out of US custody. Just the Yemenis remain.

That’s important because it corroborates something Latif has argued in his case: that the government itself didn’t rely on this document when it cleared Latif for release on multiple occasions in the past. While the newly released documents continue to redact one suspected source of inaccuracy (see PDF 91 for David Tatel’s consideration of the question), it is certainly possible the Pakistanis played a role in any inaccuracies, not least because they stood to get a bounty for each Arab “fighter” they turned over to the US.

I’ve provided the summaries of the claims against these men based on TD-314/00684-02 (the number in parentheses indicate how many other sources are cited for the claim). But particularly given that the government redacted all the rest of these reports, it seems likely the government has otherwise found the entire report unreliable.

We know that the chaos, the sheer numbers, as well as the bounty system used in our processsing of “fighters” captured at the Paksitani border in late 2001 resulted in large numbers of innocent or insignificant men to be transferred to Gitmo in 2002. Given the entirety of the record against Latif, that seems to be the case for him, too.

But, nevertheless, the government is fighting not just to keep him in custody, but to defend a dangerous precedent permitting the government to hold alleged fighters on whatever unreliable intelligence report they present.

Summaries of the other Gitmo detainees known to have been detained based on TD-314/00684-02

Mazin Salih Musaid al-Awfi (ISN 154)

Saudi citizen, released into Saudi custody July 2007, joined AQAP then returned.

Gitmo file; NYT Docket

Some details of detainee’s account have been corrborated by other detainees, such as his stay in the al-Nebras Guesthouse in Kandahar; however, detainee is assessed to have minimized his own role as a mujahid. Detainee admitted only to being present on the rear lines north of Kabul and the rear line at Tora Bora.[0]

Majid al Harbi (ISN 158)

Saudi citizen, released into Saudi custody December 13, 2006

Gitmo File; NYT Docket

After high.school,, detainee attended college for two years in Jeddah, SA studying computer sciences.[5]

On one occasion, al-Harbi [no relation] approached detainee and convinced him to go to Pakistan to conduct missionary work with JT. Detainee agreed and traveled from Jeddah to Riyadh, S.A. He then traveled to Karachi, Pakistan (PK), via Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE). In Karachi, detainee did as he had instructed by Al-Harbi, and took a taxi to the Hotel Dubai. After approximately three days, JT member Mohammed Akbar met detainee at the hotel and took him to a mosque in Lahore, PK, named Sheik Bura (NFI).[6]

Shortly after detainee arrived at the mosque, Abu Ghanim (a Kuwaiti) and Abu Abdullah (a Saudi) arrived. [5]

The Imam of the mosque, Mohammed Elias, issued a call for JT members to go to Afghanistan and fight. [2]

Abu Ghanim and Abu Abdullah traveled to a training camp for three days of training and detainee stayed in the house for five days. [7]

[a description of all the Arabs being kicked out of Kandahar, and making their way to Khost]

While at this house, detainee realized he had lost his passport. [3]

Transferred with $400 Dollars [1]

Al Juaid, (ISN 179)

Saudi citizen, released to Saudi custody July 15, 2007

Gitmo file; NYT docket

From 2000 to 2001, detainee attended the College of Technology in Mecca, SA, studying computer science, but did not complete the degree. [1]

Around July 2001, detainee traveled from Saudi Arabia to

Afghanistan via Bahrain and Karachi, Pakistan (PK).[1]

From Karachi, detainee traveled to Quetta, PK and

Kandahar, AF.[1]

Detainee then continued to Kabul. In approximately August 2001, detainee was assigned to the rear lines of the Northern front opposite the Northem Alliance (NA). Detainee remained in this position until the Taliban withdrew under heavy coalition bombardment on approximately 20 November2001.[0]

[Unsourced comment placing him at Tora Bora]

Two weeks later, detainee and a group of ten Arabs headed for Pakistan. [0]

[Description of the attack on Pakistani guards sourced to IIR 7 739 3396 02, a document used to trace 84 detainees to Kohat and, allegedly, to escaping from Tora Bora with Ibn Sheikh al-Libi]

Detainee admitted to occupying a position on the rear lines in Kabul for three months. [0]

[Unsourced assertion detainee part of 55th Arab Brigade]

Detainee stated that on approximately 20 November 2001, during flight from heavy bombardment, detainee and a small group of Arabs traveled from Kabul to Tora Bora where they stayed for two weeks under the command of Ali Mahmud. [0]

Detainee claimed that there were several hundred fighters. Most of them dispersed and broke into small groups heading for the border of Pakistan. Detainee reported that he arrived at the border on or about 20 December with a group of ten Arabs. [0]

Detainee admitted traveling to Afghanistan to participate in jihad after answering a fatwa issued by radical Shaykh Abdallah Bin Jibreen. [0]

Moammar Dokhan (ISN 317)

Gitmo file; NYT docket

Syrian. Transferred to Portugal August 28, 2009 (Miami Herald account); as of January 2010, he lived in his own apartment.

Reporting lists Abu Abdallah al-Shami from Syria as one of those who escaped from the trucks during the struggle with the soldiers and his whereabouts were unknown. (Analyst Note: This is a reference to the riot on the bus transporting prisoners noted in detainee’s capture data. Detainee is likely the al-Shami noted, though he was probably recaptured within a day of his escape.)

Mashur al Sabri (324)

Gitmo file; NYT docket

Yemeni, lost habeas petition this year

He sometimes has claimed he was born in Taiz, YM and other times in Mecca, SA, demonstrating his willingness to mislead US intelligence officials on even the most basic detail. [1]

Sharaf Masud (170)

Gitmo file; NYT docket

Yemeni, remains in custody, although there are no allegations he fought; government preparing to release public return in his habeas case, filed under Sharaf al Sanani

In September 2001, detainee decided to visit Kabul, AF, in order “to see what the city was like.” After two weeks at an unidentified location in Kabul, detainee heard on the radio that the local Afghans were killing Arabs for being the cause of the US bombing campaign in Afghanistan. Detainee decided to flee to Jalalabad, AF, and stayed at the Mujama al-Arab guesthouse for approximately six weeks. In mid-December 2001, an Afghan guide led detainee and fifty other Arabs east toward the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. They reached a small village where they resided for approximately four days at a local mosque. Detainee discarded his suitcase, which contained his passport and money, while fleeing Jalalabad. [3]

Detainee fled Afghanistan with a group of al-Qaida and Taliban fighters led by LY-212, UBL’s military commander in the Tora Bora Mountain Complex. The group crossed the Afghanistan-Pakistan border in the Nangarhar, AF region in mid-December 2001 and arrived at a Pakistani village where their local contact convinced them to surrender their weapons. The contact then gathered the group in a mosque where Pakistani forces arrested them. [2/3]

Detainee stated he traveled to Kandahar and stayed in an Arab guesthouse for sixty days prior to going to Kabul in September 2001. [0]

Detainee admitted using the alias Gharib.[0]

[Confiscation at a guest house] is probably the true disposition of detainee’s passport and supports his possible attendance at an al-Qaida affiliated training camp despite detainee’s claim that he had abandoned his suitcase and passport during his exodus from Jalalabad. [0]

Detainee admitted being part of a three vehicle convoy of prisoners transported from where they surrendered to the prison in Kohat.[0]

Abu Bakr Alahdal (171)

Gitmo file; NYT docket; Habeas public return

Yemeni who allegedly fought with the Taliban and who remains in custody

Detainee then continued to the Daftar Taliban (Taliban Office) in Quetta, PK where the office manager, Muhammad Dauod, facilitated his jihad application in Afghanistan. [1]

After four days, detainee traveled to Kabul, AF where detainee stayed at the al-Khat Guesthouse for one week.[0]

In Kabul, detainee presented himself to Taliban commander Mullah Abd al-Ahad. [0]

Detainee requested to return to the front lines after fully recovering from his illness and was assigned as a guard in a twelve-man unit, composed of nine Arabs and three Afghans. Mullah Abdul al-Ahad commanded the unit, which provided security for the Taliban rear headquarters. [2]

Detainee claimed he withdrew to a village on the outskirts of Jalalabad and hiked into the mountains where he remained for the duration of Ramadan. After six days of walking in the mountains, his group broke into two-man units to reduce suspicion. The group was aided by a Yemeni who approached a concentration of other Arabs making their way to Pakistan. Upon arrival, the villagers turned them all over to Pakistani authorities. They were taken to a police station in pickup trucks at night and later sent in a convoy of three buses toward another prison when a riot broke out in one of the other buses. [0]

Detainee stated he was proud to have been a mujahid fighting for the Islamic cause under the Taliban banner. Detainee stated he will bide his time until the next “Islamic nation” arises and he will join the fight against the enemies of Islam. Detainee remarked he was a willing terrorist against the US because of his opinion that the US holds a hostile position against Palestinian Muslims and other Arab populations. [0]

Detainee occupied Taliban and al-Qaida positions on the front lines during Operation Enduring Freedom. Detainee reported he returned to Kabul in July 2001 and spent two months recovering there before he returned to the front lines. Detainee was on the front lines until withdrawing to Jalalabad and the nearby mountain where he spent Ramadan (mid-November to mid-December) 2001 before escaping to Pakistan. [5]

Detainee was assigned to an artillery unit and is assessed to have received basic and advanced training requisite of this assignment. Detainee occupied a Taliban position north of Kabul under the command of Mullah Abdul Ahad. [0]

Al-Qadasi (163)

Gitmo file; NYT docket

Yemeni, still in custody.

An individual in Hudaydah, YM known as Juhana gave detainee $400 US, procured detainee’s Pakistani visa, and gave detainee a one-year round trip “open” ticket from Yemen to Pakistan (PK) to seek medical treatment for joint pain. Detainee’s June or July 2001 flight originated in Hudaydah, YM and continued to Sanaa, YM and then Karachi, PK. [3]

[At Tora Bora] Detainee hid in trenches until he was able to escape into Pakistan. [0]

Detainee claimed he traveled to Afghanistan in June or July 2001, but probably traveled in late 2000.[2]