BPD said they would call in FBI’s Critical Incident Response Group, which does aerial surveillance, but CIRG does not appear in unredacted parts of the documents.

The ACLU just released a series of documents about the FBI’s aerial surveillance of Black Lives Matter protests after Baltimore cops killed Freddie Gray. As they note, the documents show two different parts of FBI, the Washington Field Office and Special Flight Operations Unit, conducting electronic surveillance of protestors, using night vision and other technology. At least two of the flights were claimed to be “consensual,” which ACLU’s Nate Wessler thinks might just reflect public monitoring. Both of those consensual flights appear to have been “collected from” a third party.

Because I’m interested in what happened to one set of video cards, I’m going to do a timeline based on the flight logs and the evidence log.

The timeline shows several things:

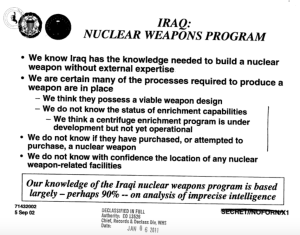

FBI did surveillance before Baltimore asked for it

The FBI conducted at least 5 surveillance flights, including several by the Washington Field Office, before a May 1 memo reflecting Baltimore Police Department (BPD) requesting help, prospectively, from Washington Field Office, though a BPD passenger had been on two Special Flights Operations Unit (SFOU) flights before then.

Of signifiant note, the memo said it would ask for help from FBI’s Critical Incident Response Group.

The potential for large scale violence and riots throughout the week presents a significant challenge for the Baltimore Police Department for airborne surveillance and observation. Baltimore will request the assistance of CIRG and WFO in the matter of airborne surveillance to assist the Baltimore Police Department.

CIRG is an elite group within FBI, and includes a Surveillance and Aviation Section, which would (presumably) have far more sophisticated aerial surveillance technology than your typical field office. Correction: It is that, but SAS also manages FBI’s airplanes generally.

CIRG’s Surveillance and Aviation Section (SAS) provides modern jets and other aircraft that respond to crisis situations domestically and around the world. SAS can deploy aviation assets worldwide, including assignments in combat theaters.

CIRG does not appear, unredacted, in any of the flight or evidence logs turned over to ACLU, but if they were involved with this surveillance it might explain some of the other odd details in these documents. As noted below, there are some other interesting redactions that might indicate CIRG involvement.

One more detail about the memo. It used looting to justify the request for help. But it also invoked online discussions among people alleged to be sovereign citizens. So they used a number of different claimed threats to justify the request for help.

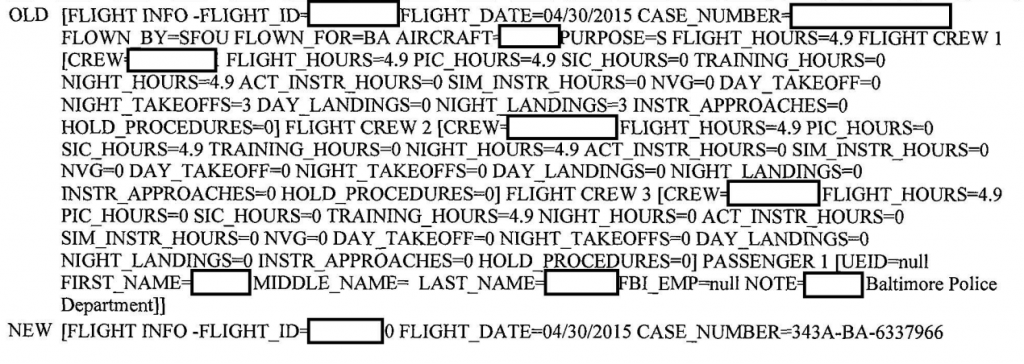

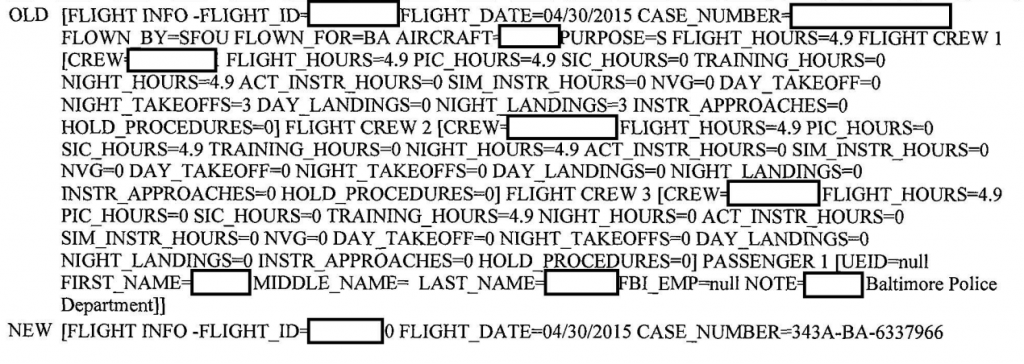

FBI changed its case number after conducting the first flights

In many cases, the flight logs show changes made in the notes associated with each flight; in such cases, the log will show both the old set of notes and the new one. For the SFOU flights logged before that memo showing BPD asking for FBI help, someone updated the flight logs with the case number that FBI has left unredacted for this release (the original case number is redacted) after that memo got written. For example, this shows SFOU updating the log from their 4/30 flight on 5/2, replacing a redacted case number with case number “343A-BA-6337966” which is the case file that all these documents are associated with.

This means SFOU originally conducted the earlier flights under a different FBI case number. This could either be another specific case, or a general number they use for standing investigations, as the FBI does both.

The Washington Field Office flights didn’t get logged until after that memo got written (they appear to all have been logged in one sitting on 5/4), so they always used the same case number.

You have to wonder how often the FBI delays doing flight logs until they have a case number to do the flight under–that likely violates protocols tying surveillance to a specific investigation.

ACLU didn’t get the flight logs for at least one flight

ACLU received flight logs for flights occurring between 4/29 and 5/3. But this document shows a flight occurring (or at least starting) on 4/28.

This might just reflect an overnight flight the night of 4/28-29 (most of these flights occurred at night), except that there are two other evidence log files for flights on 4/29 that would correlate with the two flight logs from that date. I think it’s possible this is a BPD or a different federal agency’s flight — either Secret Service or Homeland Security, which the memo says BPD was working with — though the evidence appears to have come through FBI.

One flight reflects an FBI passenger

There are, in general, one flight a day for the days logged from each part of FBI, the SFOU and WF. The exception is 4/30, when what appears to be the Baltimore office flew an FBI passenger (whose identity was redacted under a 7E, law enforcement technique, FOIA exemption). Curiously, this flight wasn’t logged until well after the actual flight, on 5/21. Note, since this is a Baltimore flight, it’s unlikely it’s someone flying in from DC to see events.

Two consensual flights appear to have come from a third party

As ACLU itself noted, some (two) of these evidence logs claim the surveillance was consensual. The two have something else in common. The entry for “collected from” (which elsewhere has unredacted descriptions where it is used, often “Aerial Surveillance Washington” or “…Baltimore”) is redacted, but it clearly shows the file is collected from a third party via an interim one.

This would seem to suggest the entity that did the surveillance is being hidden. Note, it is being hidden with a 7E law enforcement technique.

Much of this evidence didn’t get logged until a delayed evidence turnover

As I said, the reason I decided to map out this timeline is because there was a delay in some of the SD cards arriving, presumably in Baltimore, to be logged. Even the description, written on 6/1, offered to justify the delay raises questions.

The purpose of this communication is to explain the late submission of Bureau aircraft[redacted] video to the Baltimore ELSUR unit. For background, Washington Field Office (WFO) and Special Flight Operations provided airborne support for the Baltimore Division during the week of April 27, 2015. Missions were flown from April 29 through May 2. The [redacted] SD cards were shipped to the Baltimore Division via FEDEX and arrived on May 5. The FEDEX package arrived at [redacted] approximately May 8. Due to operational missions on May 9 and May 10, the [redacted] SD cards were submitted to the ELSUR unit on May 11.

For example, where were the cards that they needed to be FedExed to (presumably) Baltimore, given that WFO was supposed to be involved in this? Why is FBI redacting the receiving office? Did these SD cards need to be reviewed for sources and methods? And what explains the uncertainty — we’re talking chain of evidence, after all — about when precisely they were received?

As the timeline notes, 4 of the evidence disks were not logged until after this justification got written. This includes the 3 instances where the file was collected via a third party, as well as a Washington Surveillance video attributed to 5/2 but actually taken on 5/1. Two of these are the “consensual” videos.

4/28: Aerial surveillance Serial 4 collected, collected from Washington, WF holding, logged 5/5

4/29: Aerial surveillance Serial 5 collected, collected from “Aerial Surveillance Video, Baltimore,” logged 5/6

4/29: Aerial surveillance Serial 9 collected, collected from indicates third party, holding office Baltimore, logged 6/2

4/29: 2.6 hour night SFOU flight with 3 crew members, 1 BPD passenger, originally logged at 7:52PM on 4/30, then updated with new case number on 5/2 at 2:01AM, Risk = 0

4/29: 4.5 hour WF flight (1.5 of which were at night), 2 crew members, no passengers, originally logged at 5/4 at 2:28 PM, then updated with virtually same information (without decimals) 5/4 at 2:35PM, Risk = 18

4/30: 4.9 hour SFOU night flight with 3 crew members, 1 BPD passenger, first logged at 4/30 at 7:46 PM, then updated with new case number at 5/02 at 2:02 AM, Risk = 0

4/30: Aerial surveillance Serial 2 collected, “collected from” redacted name [a category not always used elsewhere], Washington holding, logged 5/4

4/30: 3.4 hour WF night flight with 2 crew members, first logged at 5/4 at 1:38PM, then updated with virtually same information (without decimals) 5/4 at 1:38 PM, Risk = 20

4/30: 2 hour Baltimore night flight with 1 crew member, 1 FBI passenger (hidden, in part, for b7E), first logged 5/21 at 3:23PM, Risk = 18

5/1: Aerial surveillance Serial 11 collected (surveillance start 4/30, but end 5/1), collected from redacted but via third party, Baltimore holding, logged 6/2, surveillance listed as consensual

5/1: Memo, titled to include 4/27 date but reflecting events back to 4/25, stating, “Baltimore will request the assistance of CIRG and WFO in the matter of airborne surveillance to assist the Baltimore Police Department.”

5/1: 1.4 hour SFOU night flight, with 3 crew members, 1 BPD passenger, first logged 5/1 at 1:15 AM, updated without decimals 5/1 at 1:32 AM, then updated with new case number at 5/2 at 2:02 AM Risk =0

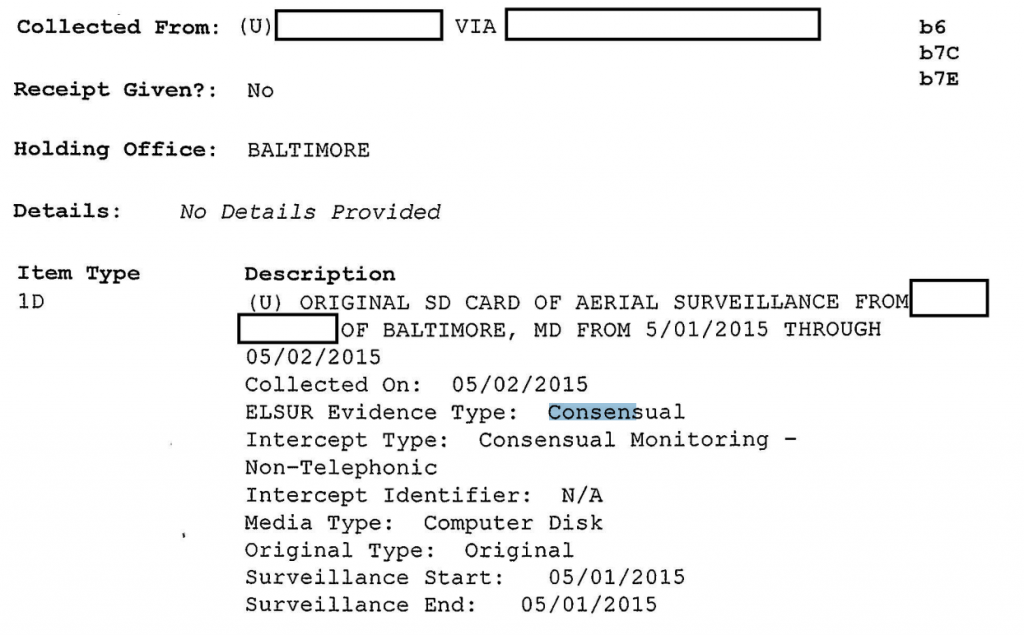

5/2: Aerial surveillance Serial 10 collected (though surveillance start and end listed as 5/1), collected from redacted, but via third party, Baltimore holding, logged 6/2, surveillance described as consensual

5/1: 5 hour WF flight (spanning night and day), with 2 crew members, first logged 5/4 at 1:58 PM then updated without decimals 5/4 at 2:00 PM Risk = 24

5/1: Aerial surveillance Serial 3 collected, collected from WF, holding Washington, logged 5/4

5/2: 3.9 hour SFOU night flight, with 3 crew members, 1 BPD passenger, first logged 5/2 at 2:03AM then updated 5/2 at , 2:04AM and 2:05AM, adding decimals, possibly changed flight ID? without Risk = 0

5/2: 4.3 hour WF flight — including training — spanning night and day, first logged 5/4 at 2:08 PM then logged 5/4 at 2:09 PM Risk = 20

5/2: Aerial surveillance Serial 8 collected, collected from Aerial Surveillance, Washington, logged 6/1

5/3: 4.2 hour SFOU flight, with 3 crew members, 1 BPD passenger, first logged 5/4 2:44 PM, then 2:45PM, then updated 5/4 4:42PM, Risk = 0

5/3: Aerial surveillance Serial 6 collected, no details on receipt from (but Baltimore, not WF, is holding office), logged 5/12

5/4: Serials 2, 3 logged

5/4?: SD cards shipped, unknown date

5/5: Serial 4 logged

5/5: SD cards shipped by FedEx arrive in Baltimore

5/6: Serial 5 logged

5/8, approximate: SD cards arrive at [location redacted]

5/9, 5/10: Operational missions disrupt logging

5/12: Serial 6 logged

6/1: Explanation for late turnover of one video, claiming missions were flown from 4/29 to 5/2

6/1: Serial 8 logged

6/2: Serial 9, 10, 11 logged