From emptywheel: Thanks to the generosity of emptywheel readers we have funded Brandi’s coverage for the rest of the trial. If you’d like to show your further appreciation for Brandi’s great work, here’s her PayPal tip jar.

The end of the Proud Boys seditious conspiracy trial may be growing closer but the hole the defendants seemingly dug themselves into this week with yet more testimony from their own witnesses has grown larger.

Testimony continued briefly this week with Tarrio’s witness George Meza. Meza is the self-proclaimed rabbi and former third-degree Proud Boy who described Jan. 6 as ‘the most patriotic act” in a century in a gushing, white power-hand-gesture-wielding video post mere days after former President Donald Trump incited a mob to descend on the U.S. Capitol.

As a witness for Tarrio, Meza was meant to credibly convince jurors that while he was admittedly once part of a rowdy, reactive brotherhood unbound by social mores, it didn’t mean that he or fellow members of the group, including its national leader, were ever part of a violent conspiracy to stop Congress from certifying the election in 2020.

Their support of Trump was prolific but to hear Meza insist upon it, it was only in a wholesome patriotic fashion, the way that any American might exercise their right to free speech and assembly.

But Meza’s claims collided, in the final hour of his appearance before jurors, with the cold reality of the prosecution’s evidence against the defendants. Impeaching Meza was often done with a sober tone from Assistant U.S. Attorney Jason McCullough.

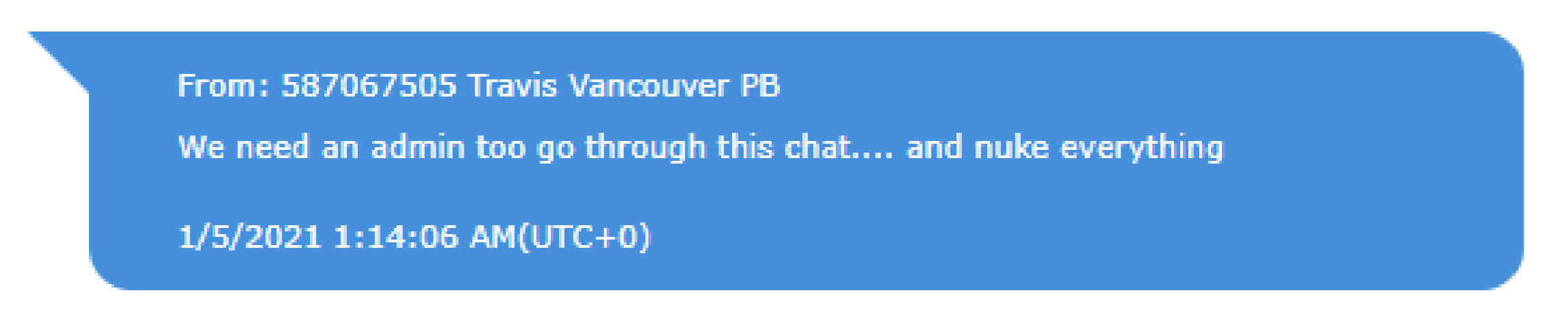

When Meza, also known as “Ash Barkoziba,” insisted he had been ousted from the exclusive text channel at the heart of the charges; Tarrio’s so-called “Ministry of Self Defense” or MOSD, by Jan. 3, McCullough presented evidence where Meza’s frantic rantings about the 6th had continued into chats dated Jan. 9.

“I can’t tell what chat this belongs to,” he said, speaking fast. “It’s hard to believe they would let me back in after they kicked me out…The average Proud Boy didn’t even know this chat existed. I question this statement if I made it at all in this chat.”

Jan. 6 was “mass hysteria” Meza later told the jury. People were simply “emoting,” he said. He denied having any understanding that police were under extreme duress when he was near the Columbus Doors seconds before they were forced open. He denied attacking the door or being part of the breach there.

And though suspicions had been raised about the truthfulness of his testimony for a little more than a day, before he left the stand he told one of Tarrio’s attorneys, Nayib Hassan, that he never received instruction from the Proud Boy leader to go to the Capitol. There wasn’t even a discussion about going there, Meza testified.

Hassan worked to elicit testimony through Meza that seemed intent to portray Tarrio as all flash and no substance, or a showboater who simply enjoyed to “razzle dazzle” the masses or antagonize the media. But objections over the scope and relevance on this count were sustained, leaving an already thin argument more impotent.

Battered by Meza’s testimony, it was followed with a First Amendment heavy defense from fourth-degree Florida Proud Boy Fernando Alonso that was rich in controversy.

Like Meza, Alonso was a member of MOSD and told the jury when he joined the chapter on Dec. 31, 2020, it was his understanding that the local D.C. division of Proud Boys didn’t want “any heat” and the Vice City member learned that other chapters of the extremist group were warned about coming to Washington on Jan. 6.

Nonetheless, Alonso came on the 5th.

And when he did, it wasn’t because there was a plan arranged to storm the Capitol, he said. Any suggestion otherwise, Alonso repeated through a gruff, often heavy accent, was “just ludicrous.”

He knew to meet at the Washington Monument, however, having consulted the MOSD chat that day, he testified, but there was “no objective” discussed. Alonso told the jury he didn’t know what was going to happen and when a video of Proud Boys shooing press away from their group as they congregated near the Capitol was played in court this week, Alonso said this wasn’t about hiding conduct.

It was because Proud Boys didn’t want to be “doxxed” and didn’t want attention on their club.

Though Alonso testified on direct that the Proud Boys weren’t doing “photo ops” on Jan. 6, another defense witness, Proud Boy Travis Nugent, said that’s exactly how he perceived things. At trial, Alonso insisted Proud Boys were “peacekeepers” on Jan. 6.

“The objective was we were going to walk towards the Capitol, stop somewhere along the line, and say a prayer. That was the only objective I knew of at that point,” he said.

Tarrio always contacted law enforcement before Proud Boys rallied, he told defense attorney Sabino Jauregui, “as he should.”

But when pressed, he testified that he never saw any messages about that himself, and he admitted to the jury, that while he considered himself a “good friend” of Tarrio who understood the ringleader’s intentions, he also never saw a single private message between Tarrio and Proud Boy elders or leaders like Nordean or Biggs.

If he had even an inkling that the plan was for Proud Boys to attack the Capitol on Jan. 6 and stop the certification, well, that would have been an affront so severe to Alonso’s sensibilities, he told the jury, “I would have left right there and then.”

Alonso elaborated on how offended he was at the suggestion that Proud Boys would incite violence. They did charity work and hurricane relief.

It “insulted” him, in fact, that people could think Proud Boys would even ponder the idea of storming the Capitol.

But in court, jurors heard and saw a different side of Alonso.

In an audio clip, he is heard breezing right over the news that a woman (Ashli Babbitt) had been shot inside the Capitol. From the grounds as people around him exclaim, he is heard only asking if then-Vice President Mike Pence had “betrayed” Trump and whether the vote had been certified.

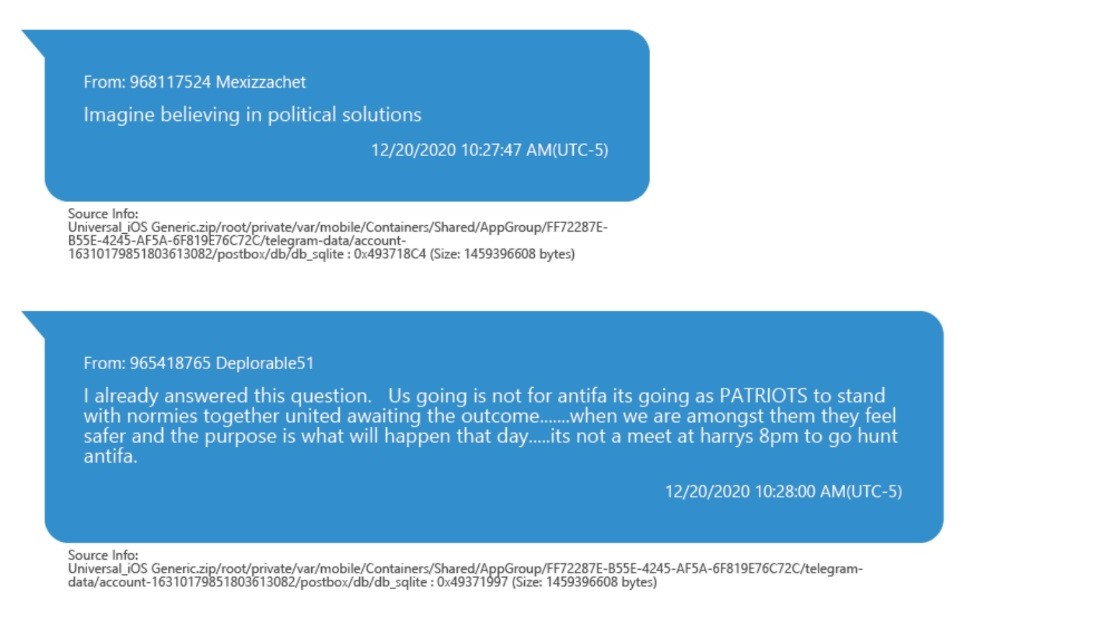

“Going on the 6th is not about fighting lefties. It’s about joining patriots on the Capitol steps and awaiting the outcome of history that affects us all,” Alonso once wrote under the handle “Deplorable51” in a message to fellow Proud Boy Michael Priest, also known as Al Tourna, on Dec. 20. Priest was brought into the Ministry of Self Defense by Tarrio, according to application records for the “ministry.”

When Tourna, who used the handle “AL PB,” told him that Jan. 6 would be the moment people would need to “take DC” and then warned that it “may not be peaceful,” Alonso didn’t shrink away.

Unlike much trial testimony from other defense witnesses who vowed the Proud Boys focus was grounded in defending the Trump-loving masses from antifa, Alonso told Priest going to the Capitol on Jan. 6 “is not for antifa.”

They were going “as patriots to stand with normies together united awaiting the outcome… when we are amongst them they feel safer and the purpose is what will happen that day…” he wrote.

“It’s not a meet at Harry’s [bar at] 8 p.m. to go hunt antifa,” he added.

Alonso had attended the Stop the Steal rally in Washington, D.C. in December 2020 with fellow Proud Boys, and on his application form for MOSD, he said he had “provided intel” to members of the extremist group while they were on the ground in D.C. for the Million MAGA March a month earlier. He stayed in Florida for that event.

Proud Boys engaged in violent clashes with counterprotesters after both of those rallies. After the rally in November, a Black woman with long braids brandishing a knife and surrounded by Proud Boys was knocked unconscious by a man who cracked a helmet over the crown of her head prompting her to crumple to the ground immediately.

Prosecutors say Alonso greeted that violence merrily.

“‘Put up the video of that predator bitch,’” Mulroe said in court, quoting Alonso’s texts found in a Miami Proud Boys channel that counted Tarrio as a member. Alonso denied writing it.

It didn’t sound like him, he said.

But Alonso joked about that violent episode and others, Mulroe told presiding U.S. District Judge Timothy Kelly this week as he fought off objections from the defense that this evidence was prejudicial and irrelevant to impeaching one of Tarrio’s few witnesses. But Mulroe convinced Judge Kelly that this show of force, appearing sanctioned by Tarrio, encouraged Alonso to return to the next pro-Trump rally in December and later, to join his fellow Proud Boys in January after Trump’s “wild” invite to Washington.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Conor Mulroe presented evidence spread out over a series of text messages where Alonso excoriated law enforcement roughly a week before he would officially be invited into the Ministry of Self-Defense by Proud Boy Gilbert Fonticoba, an intimate of Tarrio’s.

Police in D.C. backed antifa, Alonso wrote on Dec. 23. So too did the FBI. Police had turned their backs on Proud Boys when one of their brothers, Jeremy Bertino, who has already pleaded guilty to seditious conspiracy, was stabbed at the Dec. 12 event.

Weeks later on Jan. 6, when defendant Ethan Nordean spoke to a mass of Proud Boys and others gathered at the Washington Monument with a megaphone, it was he who encouraged them to “back the yellow.” Jurors saw this footage of Nordean invoking the Proud Boys black and yellow “colors” in the same way pro-law enforcement groups may invoke their slogan “back the blue.”

Nordean told the crowd just before 11 a.m. on Jan. 6 that police had let the people who stabbed Proud Boys get away last time. Tarrio had been arrested unfairly just two days before, Nordean wailed. Video footage played for the jury on March 7 showed Nordean passing the bullhorn off to defendant Joseph Biggs next.

Excitedly speaking to the crowd, Biggs told them it was their “goddamned city” and started chants of “fuck antifa.” But once Biggs would reach the location of what would be the first barrier breach of the day, Alonso testified in court this week that Biggs used the bullhorn again. This time as Proud Boys and non-Proud Boys alike were gathered near the Peace Monument less than 100 yards away from the Capitol, Biggs led chants of “Whose House, Our House” and “1776,” Alonso testified.

Prosecutors contend that Proud Boys relied on “tools” of the alleged conspiracy to pull it off and that included Proud Boys as well as non-members, the “normies” at the Capitol. In sum, the Justice Department argues Proud Boys believed they could whip the “normies” into a frenzy and this would aid them to breach barricades, subsequently overwhelm law enforcement and get inside the Capitol to stop the certification.

After the Stop the Steal rally just three weeks before the insurrection, positive attitudes toward law enforcement among Proud Boys had dried up, prosecutors allege, and the group’s anger morphed and hardened into a multi-layered paranoia: Trump’s “victory” was stolen. Cops in D.C. had sided with “antifa.” The Democrats and radical left needed to be stopped.

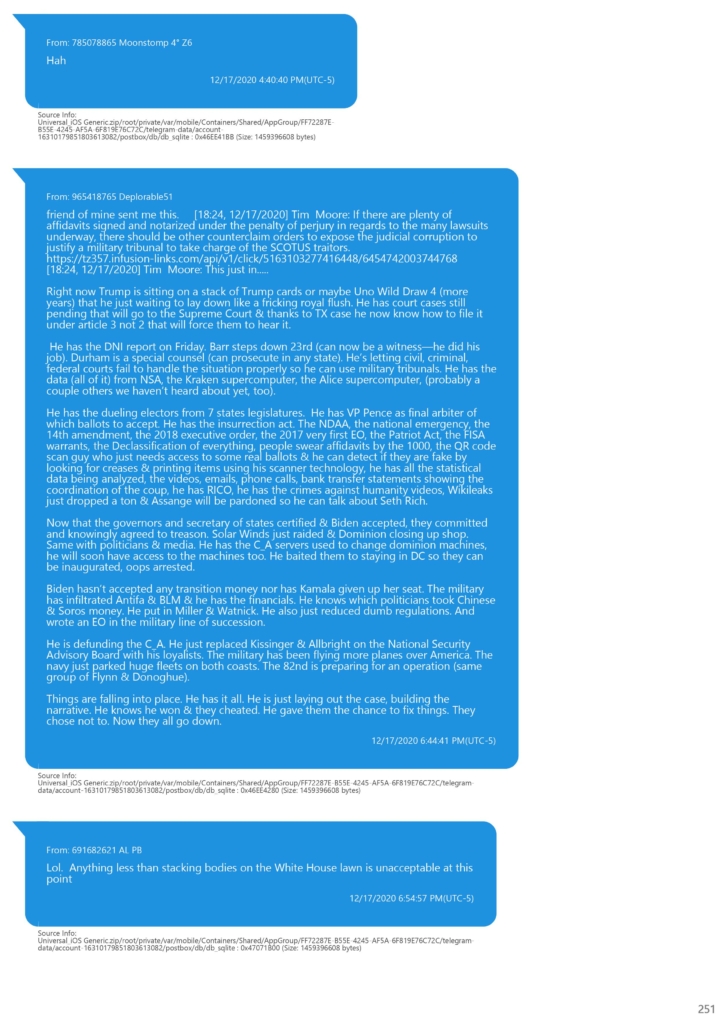

In a text chat seized off Tarrio’s phone dubbed “Croqueta Wars,” Tarrio and other Florida Proud Boys including Gabriel Garcia, George Meza, Pedro Barrios, and others, shared messages about efforts to keep Trump in power. On Dec. 17, Alonso forwarded a message to the group that laid out a “plan” for Trump to win. He had “dueling electors from 7 state legislatures [and] he has VP Pence as final arbiter of the ballots to accept,” Alonso’s friend “Tim Moore” wrote in the forward. The message was rich in conspiracy theories invoking Julian Assange, Seth Rich, and Sidney Powell’s “Kraken.”

In the transcript from Alonso’s testimony, during a sidebar with Judge Kelly, Nordean’s defense attorney Nick Smith objected to the introduction of evidence indicating Michael Priest had something a “little less complex in mind” than the theories Alonso forwarded to the Croqueta Wars chat.

While Smith argued it was irrelevant, Mulroe managed to convince Judge Kelly to let in Alonso’s exchange in the next sequence. Priest, as a member of the Ministry of Self-Defense and “tool” of the conspiracy—something Kelly agreed with during the sidebar—was fed up.

“Unleash the Kraken. Trust the plan. Blah. Blah. Blah. When do we start stacking bodies on the White House lawn?” Priest wrote.

“Jan. 7,” Alonso replied.

When Priest told him they would stack the bodies of “RINOs,” or “Republicans in Name Only” first and make Democrats watch, Alonso affirmed in court this week that he said “yes.” But it was just “locker room talk, if you will,” he said.

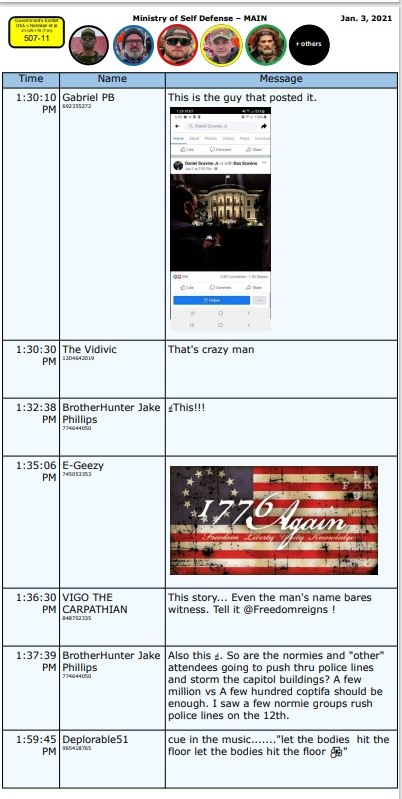

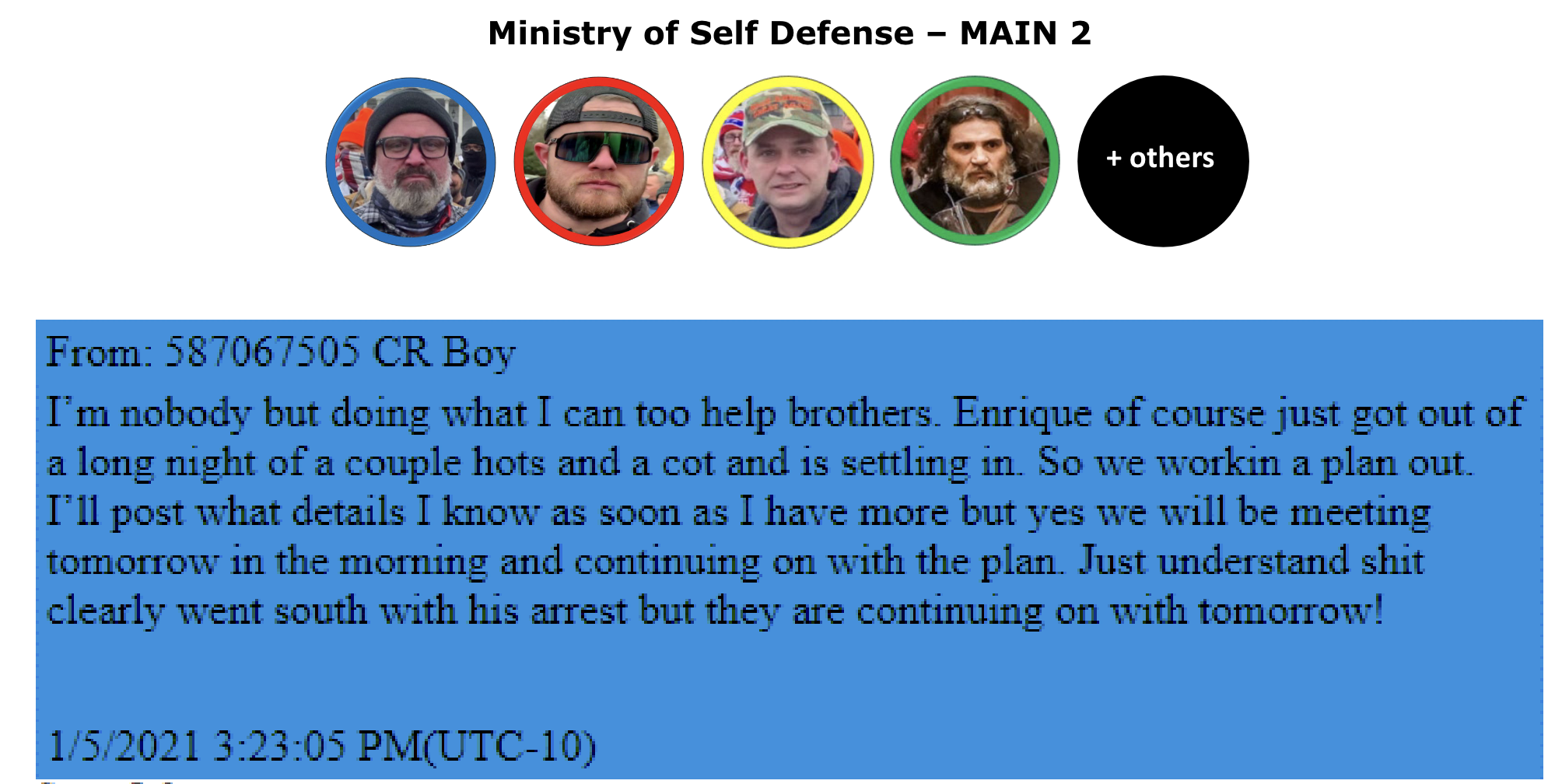

In the Ministry of Self-Defense chat on Jan. 3, a day before Tarrio would be arrested and three days before the insurrection, Gabriel Garcia shared a message with MOSD members. It was a blog post from the Hal Turner Radio Show promoting the false claim that a “1776 flag” was flying over the White House that night. But the image wasn’t new. Trump White House deputy chief of staff Dan Scavino posted an image of a colonial-era flag over the White House in June 2019 though that image was doctored too.

But Garcia seemed to believe it was realand so did others in the Ministry like one Proud Boy identified in chats only as “BrotherHunter Jake Phillps.” When Phillips asked whether the “normies and ‘other’ attendees” were going to “push thru police lines and storm the capitol buildings,” and invoked the violence that unfolded in D.C. on December, Alonso replied: “cue in the music… let the bodies hit the floor, let the bodies hit the floor.”

On direct, Alonso told Jauregui the “bodies” were “regular people” not the police. The police, he said, were going to make people hit the floor at the Capitol. On cross, he told Mulroe it was just a song. It was just locker room talk. It was all just a joke.

Norm Pattis, for Biggs, argued during a bench conference that Alonso’s comments were protected under the First Amendment and “no more prohibited than saying you’re going to line up capitalists against the wall and shoot them.”

At the end of his testimony on Tarrio’s behalf, Fernando Alonso said under oath that as far as overtaking the U.S. government was concerned or storming the Capitol, he had no part in it or wanted no part in it. It was a reprehensible suggestion. That was behavior that wouldn’t make him proud.

Yet, Mulroe pointed out to him, he sat in court today with a yellow shirt bearing the Proud Boys laurel on its chest, hiding just beneath his fleece. And he didn’t seem insulted when Priest talked about storming the Capitol. No one else seemed put off by the suggestion in MOSD either, that Alonso could recall. And though he had claimed he knew Tarrio’s intent, he wasn’t ever a witness to meetings or calls or chats that Tarrio may have had with elders, leaders, or even local police in advance of a Proud Boys official event.

There was no indication one way or the other to Alonso, Mulroe elicited, that Tarrio had even told local police Proud Boys would plan to meet at the Monument on the morning of the 6th. And he certainly had ample opportunity: Tarrio was arrested on the 4th and ordered by law enforcement to stay out of Washington after his release on the 5th.

Yet, Mulroe elicited, there was no indication that law enforcement was hipped to the Ministry of Self-Defense’s plan to gather at the Monument with what Alonso said was at least 100 men.

Alonso never went into the Capitol on Jan. 6. He never went with the defendants or anyone else that day to hear Trump, their man of the hour, speak at the Ellipse. When people were breaching the Capitol, he told the jury he thought it would be “too extreme” for anyone to go inside or past police lines. Police could shoot them, he testified. Alonso, like other Proud Boys on Jan. 6, carried a radio but like other members, he claimed “there was no communication” on it. He downplayed evidence of him railing over Proud Boy Eddie Block’s decision to circulate footage from Jan. 6 just a week after the insurrection. The wheelchair-bound Block, he told Mulroe, was doxxing them.

“Crip or not,” Alonso wrote in a Proud Boy chat. “Snitches get stitches.” He added later: “That fuck needs to be duct taped to the National Mall, his scooter placed at the top of it.”

Congress went into recess on Jan. 6 ultimately stopping the certification for several hours after the mob had rushed past police barriers, subsumed the Capitol steps, tunnels, archways, and inaugural scaffolding before streaming through broken windows or doors like the 20,000-pound Columbus Doors that were ripped from their hinges.

Tarrio, it appears now, is unlikely to testify on his own behalf.

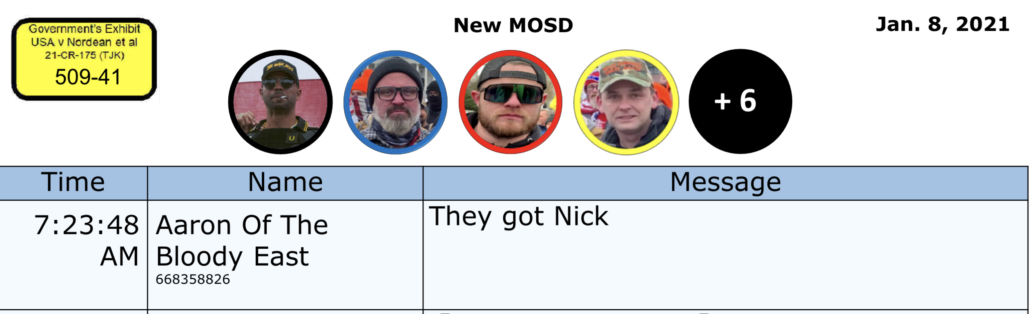

Following suboptimal testimony from Tarrio’s witnesses this week, defendant Ethan Nordean squeezed in witness testimony from an FBI confidential human source and Proud Boy who appeared in court using only his middle name, “Ehren.”

Unfortunately for the defense, “Ehren,” testified under cross-examination that he was not at the Capitol on Jan. 6 as an FBI informant in any meaningful sense. He was there, he affirmed, as a member of the Proud Boys. Though the spelling of his name was not reported into the record, “Ehren” would appear to be the individual that Jan. 6 internet sleuths have identified as “TrackSuitPB.”

In video footage, jurors could see how “Ehren” entered the Capitol carrying zip tie cuffs he said he acquired incidentally as a memento of sorts. At another point, he appears in capitol CCTV footage flanked by Kansas City Proud Boys like William “Billy” Chrestman, Chris Kuehne, and others, as he helps place a podium under an interior electric gate to keep it from closing while others set chairs in the way. Police are seen working over and over to drop the barrier as rioters advanced.

Poking holes in the defense’s direct and indirect suggestions over these many weeks of trial that the FBI was responsible for guiding the violence of Jan. 6, “Ehren” admitted he wasn’t instructed by the bureau to obstruct the gate. Or enter the Capitol. Or impede police. In hindsight, he admitted, he shouldn’t have helped prop open gates police were trying to lower at all.

While he testified, evidence was also presented to strongly support the government’s claim that he was playing up the “informing” he offered to the FBI.

“Ehren” texted his handler on Jan. 6 at 1:02 p.m. ET just as barriers were overrun: “Pb did not do it, nor inspire. The crowd did as a herd mentality. Not organized. Barriers down at capital [sic] building crowd surged forward, almost to the building now.”

During his interviews with the FBI in the summer of 2021, he claimed he was standing 100 people back from the front of the first breach. In court, however, footage showed him more like 20 or 30 people back. He was also close to defendant Zachary Rehl at one point as Rehl filmed from the fore of the crowd.

FBI Agent Nicole Miller testified earlier in the trial that in this particular clip shot by Rehl, she was able to identify the Philadelphia chapter president’s voice screaming “Fuck them! Storm the Capitol” moments before Proud Boy William “Billy” Chrestman is seen scrambling over snow fencing and outnumbered police start to run backward. “Ehren” told the jury he followed Chrestman. The crowd’s chants of “fight for Trump” reverberated as they ran closer to the Capitol. There were hundreds of people behind them, he affirmed.

When he approached the terrace of the Capitol, he said in court that he saw people topple barricades.

And yet, he told his handler that the Proud Boys didn’t inspire the breaches.

“Ehren” said he had sent his text vouching for the Proud Boys to his handler earlier than the handler received it but bad cell service caused his message to go through on delay. His testimony around the timing of the message changed over two interviews with the FBI and diverged again once he appeared in court this last week.

“Ehren” told Nordean’s attorney on direct that his handler urged him: if he saw a crime committed and was asked to talk about it, he was to be truthful with the bureau.

On cross, he testified under oath that the FBI never “embedded him” with the Proud Boys. He was tasked to report on “antifa” or leftist violence, then a focus for Trump’s Attorney General Bill Barr. “Ehren” was never part of MOSD or the Boots on Ground chat created just for Jan. 6. He said it was his local chapter president who told him to go to the Washington Monument on the 6th and not to wear Proud Boy colors. He never saw messages from Bertino or Tarrio suggesting otherwise but it would seem that information was passed down to him nonetheless. When he arrived that morning, it was clear, he testified, that Nordean was in charge.

Proud Boys were to blend in, he said, making themselves identifiable only to each other by slapping a piece of orange tape on their shoulder or arm. Antifa would infiltrate the crowds on the 6th, they believed, “Ehren” testified, and the orange tape allowed so-called Proud Boys brothers to identify each other.

Adding further ammunition to the prosecution’s “tools” argument, “Ehren” also said that Three Percenter Robert Geiswein approached him that morning and asked to march with the Proud Boys to the Capitol. “Ehren” said he told Geiswein he could stick around for a bit but once his brothers started to get on the move, he would have to go his own way.

On redirect by Dominic Pezzola’s attorney Roger Roots, “Ehren” said “Geiswein “didn’t listen very well about staying back once we met with other Proud Boys.”

Indeed, Geiswein would be spotted shoulder-to-shoulder with Pezzola on Jan. 6 just outside of the Senate Chamber.

As for “Ehren,” he wouldn’t leave the Capitol until after police told him a woman had been shot. Prior to that moment, he said, he didn’t attempt to de-escalate the situation because he figured if there was an “emergency situation” he “might be asked about it” by his handler. But this testimony ran up against video footage of “Ehren” also pumping his fist in the air in celebration after breaching.

He rather sheepishly conceded that, in the moment, it all seemed “funny” and “exciting.”

Witnesses for defendant Zachary Rehl didn’t fare much better this week, save for the largely innocuous testimony of Rehl’s wife, Amanda. Cutting a sympathetic figure, her voice was gentle as she testified and admitted to Rehl’s attorney, Carmen Hernandez, that she was nervous. They married after Rehl graduated from Temple University; she told jurors how three of her uncles were policemen and his father and grandfather were policemen, too. Jurors saw pictures of Zachary’s father and grandfather in their uniforms, including one photo of a young Rehl in tow. They also saw a photo of her child with Zachary, a cherubic-looking little girl of maybe two or three years old.

On Jan. 6, her husband, she said, left out for D.C. with Isaiah Giddings, Brian Healion, and Freedom Vy. She didn’t come. On the witness stand, Amanda Rehl said she couldn’t distinguish her husband’s voice in the video he shot from the first breach at the Peace Circle. She could hear someone say “Fuck them! Storm the Capitol” but if it was her husband’s, she couldn’t say.

Testimony from Rehl’s next witness, former West Virginia Proud Boy chapter president Jeff Finley followed.

Finley was easygoing on the stand with responses neatly tailored on direct. He pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of entering restricted grounds in last April and was sentenced to 75 days. Finley’s first reporting to prison was delayed so he could appear at the trial on Rehl’s behalf.

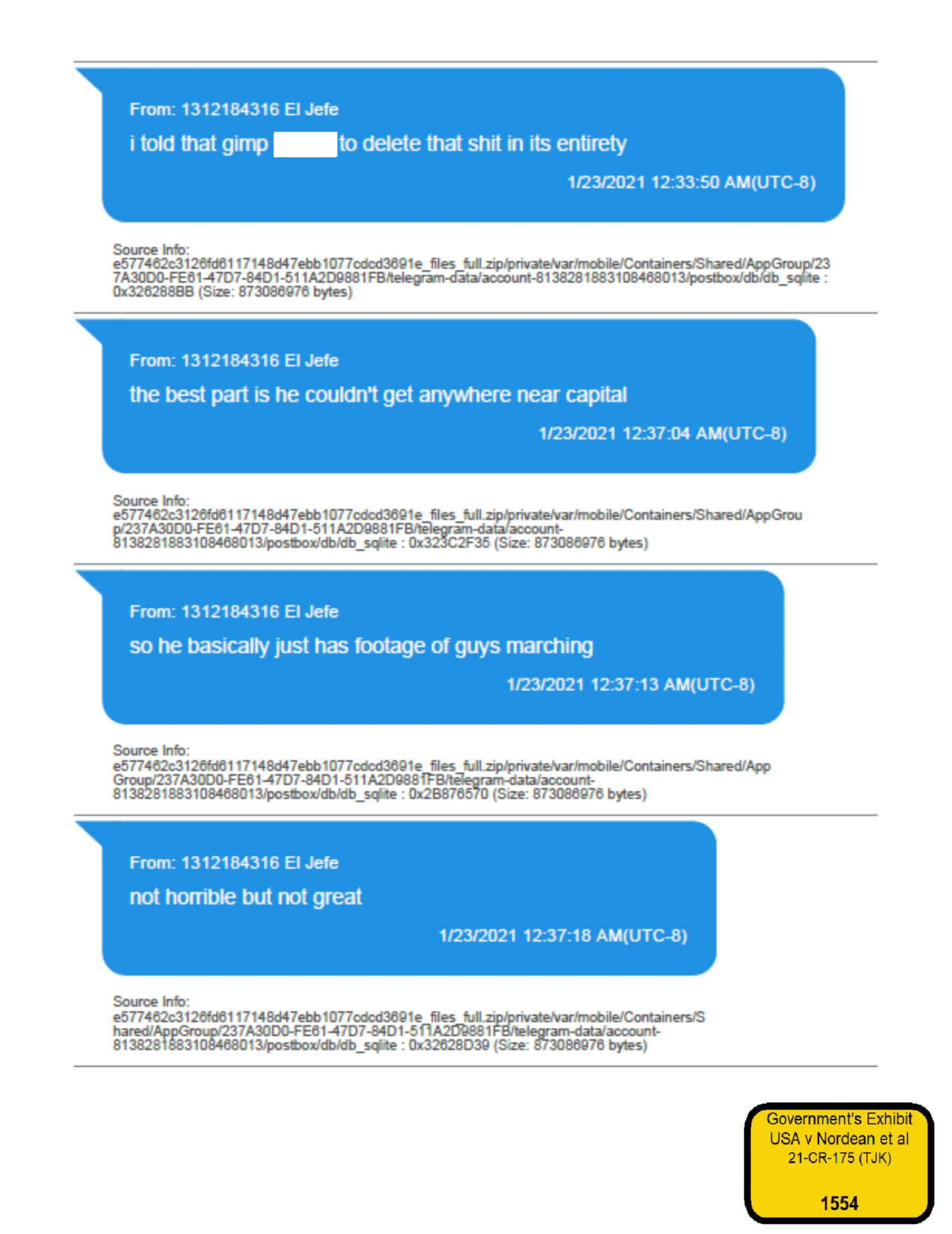

Though not a member of MOSD, he was part of the Boots on the Ground chat using the handle “El Jefe.” Finley was often in close proximity to Biggs and the co-defendants on Jan. 6 including at the west terrace where some of the worst fighting of the day occurred. He couldn’t recall whether any police officers asked him not to come inside the capitol that day, however, and he couldn’t identify any of the Proud Boys Rehl had brought to DC from Philly when Hernandez asked.

But, he testified succinctly, “no,” he didn’t do anything that day to stop legislators from certifying the election. He was in and out in 10 minutes, he said.

Finley was a fourth-degree Proud Boy deeply invested in the club—he has a tattoo etched across his chest declaring him a “West Virginia Proud Boy” jurors learned. And in the run-up to the insurrection, prosecutors brought out texts and video showing Finley looking to Nordean as the leader. In his guilty plea, he said as much to investigators and from the witness stand, Finley testified that while Proud Boys marched on the Capitol, it was Biggs, Nordean, and Charles “ Yut Yut Cowabunga” Donohoe, who would sometimes break off from the group for chats he was not privy to. Rehl, Biggs, and Donohoe did the same, he testified.

Donohoe pleaded guilty to conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding a year ago this week.

Finley told the jury he never saw any of the defendants throw projectiles at police and didn’t hear any conversations that led him to believe a plan to stop the certification was in place. He presented Jan. 6 as an opportunity he seized on to “make my voice heard” about potential discrepancies in the 2020 election.

Yet, prosecutors presented pages of text messages to the jury where Finley urged Proud Boys to delete their communications. Some of the messages showed Finley was furious with Eddie Block for filming, just like Alonso had been. In the weeks after the attack, Finley steadily discouraged Proud Boys from saving information or from having mementos, like challenge coins commemorating Jan. 6, mocked up.

“It would just place you in D.C. give more ammo against you,” he wrote on Jan. 12.

He deleted his own socials after the 6th but not before making a podcast appearance where he told the interviewer he didn’t know a single Proud Boy who was remotely close to being in the Capitol on Jan. 6.

“But you were a Proud Boy and you went in with Rehl and three other Philadelphia Proud Boys?” prosecutor Nadia Moore asked Finley in court on March 30.

He did, he admitted, but in the podcast, the host wasn’t a member of law enforcement so he was in no way obligated to tell the truth.

When the trial resumes starting Monday, it is expected that defendant Joe Biggs will start to come into focus as his attorneys, Norm Pattis and Dan Hull, make their case. Dominic Pezzola’s attorneys Steven Metcalf and Roger Roots shouldn’t be far behind. While it seemed that Biggs would likely take the stand earlier in the trial, after grueling days for the defense without any immediately obvious pay-off, that likelihood now seems low.

It may behoove Pezzola to try his luck or admit to charges that will be the hardest for him to beat because of compelling video evidence compiled by prosecutors, including video footage of him smashing open a window and allegedly stealing a police riot shield. In the first Oath Keepers case, which in many ways is quite similar to this one, defendant Jessica Watkins admitted to jurors that she impeded officers. In the end, her remorse from the stand may have helped her. She was convicted for impeding officers during a civil disorder (and conspiracy and obstruction) but she evaded a destruction of property charge despite being in the thick of a quite brutal push into the Capitol. She also was not convicted of seditious conspiracy.

The light is now visible at the end of the tunnel in this three-month-long trial and this week, parties are expected to hash out jury instructions. If there are any Hail Mary moves to be made by the remaining defendants, the window to make them is inching closed.

]

]