Egalitarianism and Markets

Posts in this series. This post is updated from time to time with additional resources.

The text for the next part of this series is Elizabeth Anderson’s Private Government: How Employers Rule Our Lives (And Why We Don’t Talk About It). The book consists of two lectures by Anderson, four responses by others, and Anderson’s replies.

Anderson considers herself to be in the philosophical tradition of Pragmatism, the subject of several posts in this series. Pragmatism is a method with which she studies egalitarianism, which is the main theme of this book. In the first posts in this series we looked closely at her ideas of freedom and equality, which are the substrate for her justifications for egalitarianism. As a pragmatist, she does not try to create an overarching theory, as we might see in other philosophic traditions. Her analysis begins with her values, as we all should. This book examines how those values are expressed in our contemporary economy, and how they might be better implemented.

In the first lecture, Anderson gives us a short history of egalitarianism in action, beginning in the 1600s. Society was almost completely hierarchical, organized under the Church of England and the Monarchy/Aristocracy structure. Most people owed obedience to both, with no say in the matter, and were forced to support both through tithes and taxes. Gradually a number of people became “masterless men”, free of obligations to one or both. Many were criminals or vagabonds, others were impoverished, but many were artisans, small shopkeepers or yeoman farmers*. These found themselves free of domination and began to see themselves as a group, not quite a class, but separate. They formed the core of Cromwell’s army in the English Civil War, 1646-51. One faction was called the Levellers. The Levellers had a number of progressive ideas, including an elected monarchy, and abolishing the House of Lords. Some even argued for the rights of women! The movement was short-lived, ending in 1651, when the rich and powerful killed them and imprisoned their surviving leaders with impunity.

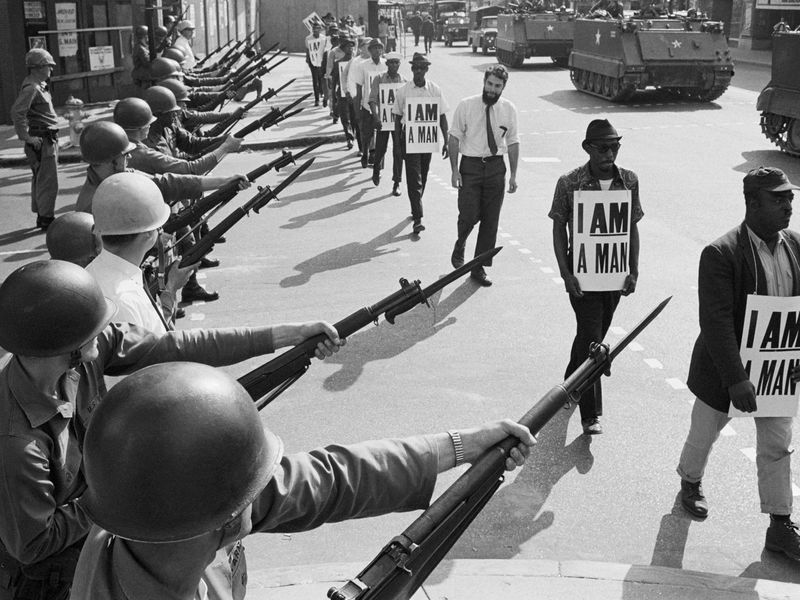

The ideas of the Levellers were egalitarian in the sense Anderson uses the term: they wanted to get rid of social hierarchies of birth, church, aristocracy, land-holdings, and perhaps even the patriarchy, and they wanted institutions that did not dominate or humiliate them because of their own birth status or employment.

Anderson says that one of their concerns was opening up monopolies granted by the Crown to aristocratic cronies, and allowing everyone to enter into any trade or business, free from interference by the Crown, the rich, and their courts. This was an attack on both royal prerogatives and the remains of the Guild system. It amounted to an attack of the prerogatives of the Church of England, which had its own courts, levied tithes, and had certain powers to discipline people.

Anderson draws from this demand the idea that people who own and manage their own capital and their own skills can meet as equals in the marketplace. It gives meaning to Adam Smith’s theory that a nation of artisans, yeoman farmers, and small retailers would be more productive and innovative than the careless and inattentive aristocracy of rich landlords and monopolists who dominated the economy. The increase in production would benefit every member of society.

In the US, Thomas Paine held similar views. There was plenty of land, so anyone could take up farming. Apprentices would become journeymen and accumulate sufficient capital to open their own businesses and eventually take on apprentices. There were no aristocracies or powerful churches in the US, so the biggest danger to this ideal was government. Anderson sees Paine as libertarian; she says that Paine’s views match those of the non-Trump conservatives.

The ideal of the US as a nation of small farms and businesses operated by self-reliant families was taken up by the Republican Party, and was embraced by Abraham Lincoln. Anderson quotes part of Lincoln’s 1859 speech to the Wisconsin Agricultural Society in which he lays out this idea. Lincoln is responding to a speech by a South Carolina Senator, James Hammond. Hammond, a wealthy plantation owner, argued that society can only advance if there are classes of people whose only role is performing menial labor, just as a house cannot stand without a mudsill, a foundation. Lincoln explains that labor is the “source by which human wants are mainly supplied”. He says that one group argues that capital is primary, that productive work is not done unless people with capital use workers to do it, and the only question is whether they hire workers or buy slaves. Others, says Lincoln

… hold that labor is prior to, and independent of, capital; that, in fact, capital is the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed — that labor can exist without capital, but that capital could never have existed without labor. Hence they hold that labor is the superior — greatly the superior — of capital.

…In [the] Free States, a large majority are neither hirers or hired. Men, with their families — wives, sons and daughters — work for themselves, on their farms, in their houses and in their shops, taking the whole product to themselves, and asking no favors of capital on the one hand, nor of hirelings or slaves on the other. … Again, as has already been said, the opponents of the “mud-sill” theory insist that there is not, of necessity, any such thing as the free hired laborer being fixed to that condition for life. There is demonstration for saying this. Many independent men, in this assembly, doubtless a few years ago were hired laborers. And their case is almost if not quite the general rule.

The prudent, penniless beginner in the world, labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land, for himself; then labors on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him. This, say its advocates, is free labor — the just and generous, and prosperous system, which opens the way for all — gives hope to all, and energy, and progress, and improvement of condition to all. If any continue through life in the condition of the hired laborer, it is not the fault of the system, but because of either a dependent nature which prefers it, or improvidence, folly, or singular misfortune.*

Lincoln describes two competing theories of the role of capital in society: the mud-sill theory, and the Free Labor system. Anderson asks why the egalitarian vision of Free Labor died out in practice, although not in the imagination of the defenders of capital and their PR flacks. I ask why the mudsill ideology became dominant.

====

*In the first response, the historian Ann Hughes provides needed context on this point, as well as a more nuanced view of the Levellers and other dissidents of their time.

*The next paragraph is pure Lincoln, the reason we love him:

By the “mud-sill” theory it is assumed that labor and education are incompatible; and any practical combination of them impossible. According to that theory, a blind horse upon a tread-mill, is a perfect illustration of what a laborer should be — all the better for being blind, that he could not tread out of place, or kick understandingly. According to that theory, the education of laborers, is not only useless, but pernicious, and dangerous. In fact, it is, in some sort, deemed a misfortune that laborers should have heads at all. Those same heads are regarded as explosive materials, only to be safely kept in damp places, as far as possible from that peculiar sort of fire which ignites them. A Yankee who could invent strong handed man without a head would receive the everlasting gratitude of the “mud-sill” advocates.