There’s something missing from coverage of the claim, made in the second-to-last sentence of a Speedy Trial filing submitted Wednesday, that David Weiss will indict Hunter Biden before September 29, when — according to calculations laid out by prosecutor Leo Wise in the filing — the Speedy Trial Act mandates an indictment.

None of the coverage has considered why David Weiss hasn’t already charged the President’s son.

The filing was submitted in response to an August 31 order from Judge Maryellen Noreika; its very last sentence politely asked her to butt out: “[T]he Government does not believe any action by the Court is necessary at this time.” Given the unusual nature of this legal proceeding, there may at least be question about Wise’s Speedy Trial calculations. One way or another, though, the Speedy Trial clock and the statute of limitations (which Wise said in July would expire on October 12) are ticking.

It would take probably half an hour to present the evidence for the weapons charge — which would consist of the form Hunter signed to purchase a gun, passages from Hunter’s book, a presumed grand jury transcript from Hallie Biden, and testimony from an FBI agent — to a grand jury. It would take maybe another ten minutes if Weiss wanted to add a false statements charge on top of the weapons charge. There certainly would be no need for a special grand jury.

Any tax charges would be more complicated, sure, but they would be in one or another district (probably Los Angeles), ostensibly severed from the weapons charge to which the misdemeanors planned as part of an aborted plea deal were linked.

So why wait? Why not simply indict and avoid any possible challenge to Speedy Trial calculations?

The answer may lie in something included in a long NYT story citing liberally from an anonymous senior law enforcement official who knew at least one thing that only David Weiss could know. That story explains that Weiss sought Special Counsel status, in part, to get, “added leverage in a revamped deal with Mr. Biden.”

If Weiss indeed sought Special Counsel status to get leverage for a deal, then at least last month when he asked for it, he wasn’t really planning on indicting Hunter Biden. He was hoping to get more tactical leverage to convince Hunter Biden to enter into a plea agreement that would better satisfy GOP bloodlust than the plea that failed in July.

Now he has used the opportunity presented by Noreika’s order to claim he really really is going to indict Hunter, a claim that set off predictably titillated reporting about the prospect of a Hunter Biden trial during the presidential election.

Again, if you’re going to charge Hunter Biden with a simple weapons charge, possibly a false statements charge, why not do it already, rather than threatening to do it publicly? Why not charge him in the week after Noreika entered that order, mooting all Speedy Trial concerns?

Abbe Lowell appears unimpressed with Weiss’ promised indictment. He repeated in both a separate filing and a statement to the press that Weiss can’t charge Hunter because he already entered into a diversion agreement pertaining to the charge.

We believe the signed and filed diversion agreement remains valid and prevents any additional charges from being filed against Mr. Biden, who has been abiding by the conditions of release under that agreement for the last several weeks, including regular visits by the probation office. We expect a fair resolution of the sprawling, five-year investigation into Mr. Biden that was based on the evidence and the law, not outside political pressure, and we’ll do what is necessary on behalf of Mr. Biden to achieve that.

I think few stories on this have accounted for the possibility that that statement — “we’ll do what is necessary … to achieve” a fair resolution of the case — is as pregnant a threat as DOJ’s promise to indict in the next several weeks. That’s because everything leading up to David Weiss obtaining Special Counsel status actually squandered much of any leverage that Weiss had, and that’s before you consider the swap of Chris Clark as Hunter’s lead attorney for the more confrontational Lowell, making Clark available as a witness against Weiss.

As Politico (but not NYT, working off what are presumably the same materials) laid out, Hunter’s legal team has long been arguing that this investigation was plagued by improper political influence.

But even before the plea deal was first docketed on June 20, the GOP House started interfering in ways that will not only help Abbe Lowell prove there was improper influence, but may well give him unusual ability to go seek for more proof of it.

It appears to have started between the time the deal was struck on June 8 and when it was docketed on June 20. AUSA Lesley Wolf, who had negotiated the deal, was replaced by Leo Wise and others. When Weiss claimed, with the announcement of the deal, that the investigation was ongoing and he was even pursuing dodgy leads obtained from a likely Russian influence operation, it became clear that the two sides’ understanding of the deal had begun to rupture. This is the basis of Lowell’s claim that Weiss reneged on the deal: that Weiss approved an agreement negotiated by Wolf but then brought in Wise to abrogate that deal.

Whatever the merit of Lowell’s claim that the diversion agreement remains in place — the plea deal was such a stinker that both sides have some basis to defend their side of that argument — by charging Hunter, Weiss will give Lowell an opportunity to litigate the claim that Weiss reneged on the diversion agreement, and will do so on what may be the easier of the two parts of the plea agreements to make a claim that Weiss reneged on a deal, with Judge Noreika already issuing orders to find out why this stinker is still on her docket. I’m not sure how Lowell would litigate it — possibly a double jeopardy challenge — but his promise to do what’s necessary likely guarantees that he will litigate it. He’ll presumably do the same if and when Weiss files tax charges in California. It’s not necessarily that these arguments about reneging on a deal will, themselves, work, but litigating the issue will provide opportunity to introduce plenty more problems with the case.

That’s part of what was missed in coverage of this development this week. Weiss promised to indict. Lowell responded, effectively, by challenging the newly-minted Special Counsel to bring it on, because it will give Lowell opportunity to substantiate his claim that Weiss reneged on a deal because of political influence.

And those IRS agents claiming to be whistleblowers have only offered gift after gift to Lowell to destroy their own case. In their own testimony they revealed:

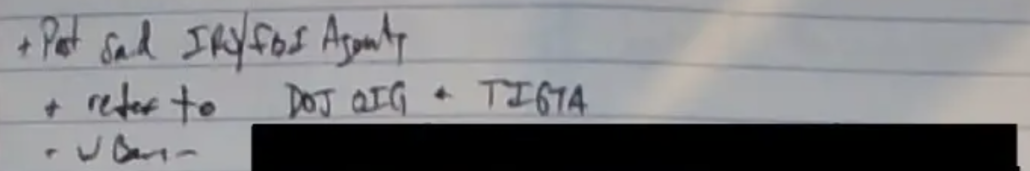

- From the start, a supervisor documented concerns about improper influence and Sixth Amendment problems with this investigation

- Joseph Ziegler, the IRS agent who improbably claims to be a Democrat, treated such concerns as liberal bias, evincing political bias on his own part

- DOJ didn’t do the most basic due diligence on the laptop and may have used it in warrants, creating poisonous fruit problems

- Ziegler treated key WhatsApp messages obtained with a later warrant with shocking sloppiness, and may even have misidentified the interlocutors involved

- Ziegler didn’t shield himself from the taint of publicly released laptop materials (and Shapley was further tainted by viewing exhibits during his deposition)

- Gary Shapley is hiding … something … in his emails

These two self-proclaimed whistleblowers have made evidence from this case public — all of which would never have seen the light of day if Weiss had honored the plea agreement — without the filter of a prosecutor to clean it up in advance.

All that’s before you consider the rampant leaking.

In both their depositions and their giddy public testimony before the House both Shapely and Ziegler did plenty of things that will provide basis to impeach them, not just as witnesses, but even as investigators, as did their anonymous FBI agent colleague’s laughable claim in his deposition that this was not an investigation riddled with leaks. James Comer seems intent on inviting all the other investigators who have complained they weren’t able to bulldoze rules designed to protect sensitive investigations to be deposed in an adversarial setting, which will provide still more surface area that Lowell can attack.

The gun charge is simple. But what investigative witnesses would present any tax case against Hunter Biden and would their testimony be impressive enough to sustain a case after Lowell serially destroyed Ziegler as the key investigator? And because Weiss has left Lowell with a viable claim that the diversion remains valid, he may be able to introduce the taint of the tax case into any gun prosecution.

Some of this shit goes on in any case, though not usually this much with politically exposed people like the President’s son. But prosecutors have a great number of tools to prevent defendants from learning about it or at least keeping it off the stand. Many of the IRS agents’ complaints were really complaints about Lesley Wolf’s efforts to preserve the integrity of the case. By bitching non-stop about her efforts, the IRS agents have ensured that Hunter Biden will get access to everything that Wolf tried hard to stave off from the investigation.

And there’s something more. Ziegler provided the name of his initial supervisor, who documented concerns that this case was politicized from the start. Both IRS agents identified for Lowell a slew of irregularities he can use to undermine any case. Republicans in Congress have bent over backwards to expose witnesses against Hunter to adversarial questioning (and both IRS agents got downright reckless in their public testimony). The way in which this plea collapsed provides Lowell reason to challenge any indictment from the start.

But the collapse also provided something else, as described in the NYT story: a David Weiss associate told the NYT that Weiss told them that any other American would not be prosecuted on the evidence against Hunter.

Mr. Weiss told an associate that he preferred not to bring any charges, even misdemeanors, against Mr. Biden because the average American would not be prosecuted for similar offenses. (A senior law enforcement official forcefully denied the account.)

If this witness makes themselves available to Lowell, it provides him something that is virtually unheard of in any prosecution: Evidence to substantiate a claim of selective prosecution, the argument that Weiss believes that similarly situated people would not have been prosecuted and the only reason Hunter was being prosecuted was because of non-stop GOP bloodlust that originated with Donald Trump. It is darn near impossible for a defense attorney to get discovery to support a selective prosecution claim. Weiss may have given Lowell, one of the most formidable lawyers in the country, a way to get that discovery.

And all that’s before Lowell unveils whatever evidence he has that Joseph Ziegler watched and did nothing as Hunter Biden’s digital life was hijacked, possibly by people associated with the same Republicans driving the political bloodlust, possibly by the very same sex workers on which the case was initially predicated. That’s before Lowell unveils evidence that Ziegler witnessed what should have been clear alarms that Hunter Biden was a crime victim but Ziegler chose instead to trump up a weak criminal case against the crime victim. I suspect that Weiss doesn’t know what Lowell knows about this, either, adding still more uncertainty to any case he charges.

Over four weeks ago, Leo Wise asked Noreika to dismiss the misdemeanor tax charges against Hunter so they could charge them in another venue.

In light of that requirement, and the important constitutional rights it embodies, the Government moves the Court to dismiss the information without prejudice so that it may bring tax charges in a district where venue lies.

Now he and Weiss have made promises of another upcoming indictment, without yet charging it. At the very least, that suggests that there are a number of challenges to overcome before they can charge Hunter.

They likely still have time on any 2019 tax charges — the ones where, reportedly, both sides agree that Hunter overstated his income, which will make a tax case hard to prove. I’m not saying that Weiss won’t charge Hunter. Indeed, he has backed himself into a corner where he likely has to. But with each step forward, Lowell has obtained leverage to make Weiss’ own conduct a central issue in this prosecution (and even Wise may have made himself a witness given the centrality of his statements during the plea colloquy to Lowell’s claim that the diversion remains valid).

The Speedy Trial filings seem to have hinted at an intense game of chicken between Weiss and Lowell. And thus far at least, Weiss seems more afraid of a Hunter Biden indictment than Lowell is.