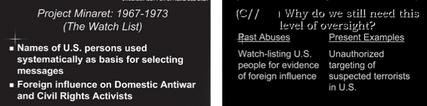

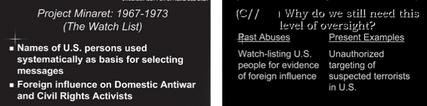

For weeks, I have been trying to figure out why the NSA, in a training program it created in August 2009, likened one of its “present abuses” to Project Minaret. What “unauthorized targeting of suspected terrorists in the US” had they been doing, I wondered, that was like “watch-listing U.S. people for evidence of foreign influence.”

Until, in a fit of only marginally related geekdom, I re-read the following passage in Keith Alexander’s declaration accompanying the End-to-End review submitted to the FISA Court on August 19, 2009 (that is, around the same time as the training program).

Between 24 May 2006 and 2 February 2009, NSA Homeland Mission Coordinators (HMCs) or their predecessors concluded that approximately 3,000 domestic telephone identifiers reported to Intelligence Community agencies satisfied the RAS standard and could be used as seed identifiers. However, at the time these domestic telephone identifiers were designated as RAS-approved, NSA’s OGC had not reviewed and approved their use as “seeds” as required by the Court’s Orders. NSA remedied this compliance incident by re-designating all such telephone identifiers as non RAS-approved for use as seed identifiers in early February 2009. NSA verified that although some of the 3,000 domestic identifiers generated alerts as a result of the Telephony Activity Detection Process discussed above, none of those alerts resulted in reports to Intelligence Community agencies. 7

7 The alerts generated by the Telephony Activity Detection Process did not then and does not now, feed the NSA counterterrorism target knowledge database described in Part I.A.3 below. [my emphasis]

As I’ll explain below, this passage means 3,000 US persons were watch-listed without the NSA confirming that they hadn’t been watch-listed because of their speech, religion, or political activity.

Here’s the explanation.

The passage actually appears in an entirely different part (PDF 37, document 81) of Alexander’s declaration from his discussion of the alert list violations (PDF 30, document 74) that started the review of the phone dragnet program. But given the February (2009) timing and the discussion of Telephony Activity Detection alerts, this passage clearly addresses alerts violations.

Before I parse the passage, a few reminders about the NSA’s multiple metadata dragnets and the alert system.

The NSA has an interlocking system of metadata query interfaces which we now know mix EO 12333 collected data with data collected under the US based phone and Internet dragnet programs. Data collected overseas is dumped in with data collected directly from Verizon.

The interlocking system apparently does a lot of nifty things, one of which is to alert NSA if any of a watch-list of numbers have had certain kinds of phone activity in the previous day (the NSA has not explained what it does when it receives such alerts, which is part of the issue here). There were over 17,000 people on that list when the NSA first started cleaning up its phone dragnet problem.

The problem with having all that data mixed up in one system is that the standards for access are different based on where the data came from. For EO 12333 collected data (the data collected overseas) there’s a foreign intelligence assumption that requires only a valid foreign intelligence purpose; this data can be accessed fairly broadly.

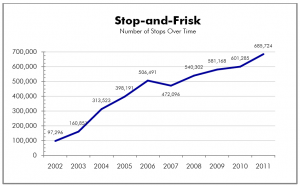

Whereas both the phone (BR) and Internet (PR/TT) dragnets — in which the data was collected by legal process in the United States — require “Homeland [ack!] Mission Coordinators” within the NSA to sign off on a claim that there is Reasonable Articulable Suspicion that the identifier belongs to someone with a tie to certain approved terror (and Iran) groups — it’s basically a digital stop-and-frisk standard signed off by a manager.

That difference between EO 12333 and domestic dragnets created the first problem with the alert list: 90% of the people on the alert list had not had that bureaucratic sign-off, and so should not have been used with the BR phone dragnet data at all. That’s the part of the alert problem we hear most about.

But in addition to the “RAS approval” step for the BR phone dragnet, there’s an additional bureaucratic step for US persons.

The statute only permits Section 215 to be used against Americans,

provided that such investigation of a United States person is not conducted solely upon the basis of activities protected by the first amendment to the Constitution.

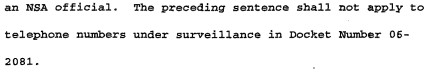

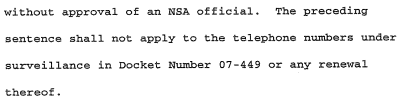

The FISC orders (here’s the one in place when NSA first started admitting the problem) accomplished that by reiterating that restriction (7-8) and mandating that,

NSA’s OGC shall review and must approve proposed queries of archived metadata based on “seed” telephone identifiers reasonably believed to be used by U.S. persons before any query is conducted. (8-9)

Note the “archived metadata” language. The NSA maintained that since the alert process happened as the data came into the database, that didn’t count as a query of archived metadata. Judge Walton was not impressed.

The NSA had to get its lawyers to sign off on an assertion that the US person identifiers they were using to query the database had not been selected based solely on their religion, their speech, or political activity.

In other words, before NSA could use that US person’s identifier either to query the dragnet (which produces a three-degrees of Osama bin Laden report) or to generate alerts, they should have had it RAS-approved by a Homeland [sic] Mission Coordinator and undergo a First Amendment review at OGC.

When I was first learning how to write effective bureaucratic documents 20 years ago, I learned that “shall” is the only magic word that can make people do what they’re supposed to do; it’s the only thing that conveys legal obligation. Apparently it didn’t work out that way in this case, because 3,000 US persons — 58% more people than were on the Project Minaret watchlist, which extended over 3 more years — were on (at a minimum) the alert list without that First Amendment review.

3,000 US persons (that is, either permanent residents or American citizens) were having their communications tracked because of a stop-and-frisk standard suspected tie to terrorism, without NSA affirming that they weren’t being tracked because they were politically active Muslims or similar protected behavior.

Retrospectively, it’s now clear that this exposure of Americans without First Amendment review was chief among Reggie Walton’s concerns when he first responded to the dragnet. It’s equally clear that Walton was just learning about the EO 12333 data on the alert list, including that US persons might be included on it.

The preliminary notice from DOJ states that the alert list includes telephone identifiers that have been tasked for collection in accordance with NSA’s SIGINT authority. What standard is applied for tasking telephone identifiers under NSA’s SIGINT authority? Does NSA, pursuant to its SIGINT authority, task telephone identifiers associated with United States persons? If so, does NSA limit such identifiers to those that were not selected solely upon the basis of First Amendment protected activities?

DOJ and Keith Alexander were in no rush to answer Walton’s question — the only unredacted response to his question about what happened with US persons The NSA explained,

Additionally, NSA determined that in all instances where a U.S. identifier served as the initial seed identifier for a report (22 of the 275 reports), the initial U.S. seed identifier was either already the subject of FISC-approved surveillance under the FISA or had been reviewed by NSA’s OGC to ensure that the RAS determination was not based solely on a U.S. person’s first amendment-protected activities.

That response was dated February 12, 2009, so Walton’s response may have been to point out that alerts were effectively queries and a bunch of Americans were being tracked illegally. Note, too, that they’re only telling Walton about queries that resulted in report to the FBI or some other agency; they’re not denying that these identifiers were used for queries, which would have resulted in the numbers of their contacts being dumped into the corporate store forever.

But there are a few more details from Alexander’s declaration, above, that should cause us concern:

- Rather than review these selectors to see if they had been selected based on their speech, religion, or politics, NSA’s OGC simply moved them into a category — non-RAS approved — where such restrictions no longer applied. I would suggest their unwillingness to do such a review is rather striking.

- “Some of the 3,000 domestic identifiers generated alerts as a result of the Telephony Activity Detection Process.” They shouldn’t have been matched up against the incoming phone dragnet data, but it appears they were, and did produce those kinds of alerts, though NSA rather conspicuously declines to tell us how many people that happened to and how often. We don’t know what happened to these 3,000 US person or the people they communicated with after NSA discovered these daily contacts.

- The footnote notes that being on the alert list does not automatically put one in the “counterterrorism target knowledge database,” NSA’s tracker for suspected terrorists. But the footnote doesn’t say that they weren’t put in that database, potentially in part because of the alerts. Moreover, these “approximately 3,000 domestic telephone identifiers” had already gotten “reported to Intelligence Community agencies.” While NSA makes much out of the fact that no query reports got sent on to the FBI and other agencies, that’s sort of moot, because the identifiers, if not the names, already had been.

Mind you, to get disseminated to other agencies, these US person identities (if they were treated as such) would need to get sign-off for their intelligence value. Which is why I find OGC’s solution — to avoid doing a First Amendment review on them at all — so suspicious. Because high ranking NSA personnel had already done a review, and for some reason were unwilling to do further scrutiny.

3,000 US persons were on a watchlist, potentially because of their religion, politics, or speech. The NSA itself appears to have seen the similarities with Project Minaret, decades earlier.

But we keep hearing there were no abuses.

Updated erroneous link to Keith Alexander declaration.

Update, March 11: The NSA actually did provide more response on EO 12333 collection to Walton, which I hope to return to.