In addition to suggesting that the 16 year old American citizen Abdulrahman al-Awlaki was a legitimate military target, Jeh Johnson spoke yesterday about the “military’s domestic legal authority.” Now, rest assured, Johnson said the Administration does not rely on aggressive interpretations of such authority.

Against an unconventional enemy that observes no borders and does not play by the rules, we must guard against aggressive interpretations of our authorities that will discredit our efforts, provoke controversy and invite challenge.

He acknowledges that posse comitatus requires express authorization from Congress before extending the reach of the military onto US soil.

As I told the Heritage Foundation last October, over-reaching with military power can result in national security setbacks, not gains. Particularly when we attempt to extend the reach of the military on to U.S. soil, the courts resist, consistent with our core values and our American heritage – reflected, no less, in places such as the Declaration of Independence, the Federalist Papers, the Third Amendment, and in the 1878 federal criminal statute, still on the books today, which prohibits willfully using the military as a posse comitatus unless expressly authorized by Congress or the Constitution. [my emphasis]

Then he proceeds directly from describing the express authorization required from Congress to a discussion of the AUMF–as the basis for the “military’s domestic legal authority.”

Second: in the conflict against al Qaeda and associated forces, the bedrock of the military’s domestic legal authority continues to be the Authorization for the Use of Military Force passed by the Congress one week after 9/11.[2] “The AUMF,” as it is often called, is Congress’ authorization to the President to:

use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

Ten years later, the AUMF remains on the books, and it is still a viable authorization today. [my emphasis]

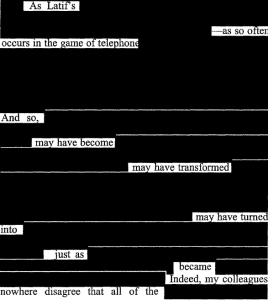

Then Johnson describes how the Administration–with no express authority from Congress until the NDAA–stretched an authorization limited to those people and groups with ties to 9/11 to include those “associated with” such groups. And, again with no express authorization from Congress, expanded it to include those who “engaged in hostilities” with coalition partners.

In the detention context, we in the Obama Administration have interpreted this authority to include:

those persons who were part of, or substantially supported, Taliban or al-Qaeda forces or associated forces that are engaged in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners.[3]

This interpretation of our statutory authority has been adopted by the courts in the habeas cases brought by Guantanamo detainees,[4] and in 2011 Congress joined the Executive and Judicial branches of government in embracing this interpretation when it codified it almost word-for-word in Section 1021 of this year’s National Defense Authorization Act, 10 years after enactment of the original AUMF.[5] (A point worth noting here: contrary to some reports, neither Section 1021 nor any other detainee-related provision in this year’s Defense Authorization Act creates or expands upon the authority for the military to detain a U.S. citizen.)

Johnson doesn’t mention, of course, that the government is using the same interpretation to extend the military’s domestic legal authority to non-detention areas. Those applications are secret, you see.

Note, in this passage, how Johnson gracefully re-specifies that he’s talking about the 2001 AUMF, and not the 2002 AUMF, which also remains in effect?

But, the AUMF, the statutory authorization from 2001, is not open-ended. It does not authorize military force against anyone the Executive labels a “terrorist.” Rather, it encompasses only those groups or people with a link to the terrorist attacks on 9/11, or associated forces.

That’s important because the government at least used to–and presumably still does (otherwise they wouldn’t have panicked when Congress considered repealing the AUMF authorizing a war that is supposed to be over)–rely on the Iraq AUMF to target “anyone the Executive labels a ‘terrorist.’”

Given that the Iraq AUMF has been used to go beyond the definitions in the 2001 AUMF, I’ll skip the paragraphs were Johnson talks about how narrow the government’s interpretation of “associated forces” is.

Particularly because this paragraph is my very favorite bit in this entirely disingenuous speech.

Third: there is nothing in the wording of the 2001 AUMF or its legislative history that restricts this statutory authority to the “hot” battlefields of Afghanistan. Afghanistan was plainly the focus when the authorization was enacted in September 2001, but the AUMF authorized the use of necessary and appropriate force against the organizations and persons connected to the September 11th attacks – al Qaeda and the Taliban — without a geographic limitation.

Pretty comprehensive, huh, Jeh? Neither the wording of the AUMF or the legislative history limits the AUMF, right?

That of course leaves out what Tom Daschle has said explicitly.

Just before the Senate acted on this compromise [AUMF] resolution, the White House sought one last change. Literally minutes before the Senate cast its vote, the administration sought to add the words “in the United States and” after “appropriate force” in the agreed-upon text. This last-minute change would have given the president broad authority to exercise expansive powers not just overseas — where we all understood he wanted authority to act — but right here in the United States, potentially against American citizens. I could see no justification for Congress to accede to this extraordinary request for additional authority. I refused.

Jeh Johnson, you see, admits that the military needs express authority from Congress to operate within the US. Congress expressly refused to grant that authority. Johnson knows that, surely. Nevertheless, there he was yesterday, laying out the “military’s domestic legal authority” that Congress never expressly authorized.

Remember, “domestic legal authority,” he’s talking about, not–or not just–international legal authority. Which is why this passage is so funny.

The legal point is important because, in fact, over the last 10 years al Qaeda has not only become more decentralized, it has also, for the most part, migrated away from Afghanistan to other places where it can find safe haven.

However, this legal conclusion too has its limits. It should not be interpreted to mean that we believe we are in any “Global War on Terror,” or that we can use military force whenever we want, wherever we want. International legal principles, including respect for a state’s sovereignty and the laws of war, impose important limits on our ability to act unilaterally, and on the way in which we can use force in foreign territories. [my emphasis]

In the context of talking about the military’s domestic legal authority, Jeh Johnson says that state sovereignty will protect us. Not the Tenth Amendment, mind you, but the sovereign right of other states to keep the US out.

But who will keep the US out of the US?

I guess Johnson was relying on the kids at Yale Law being credulous when he said the Administration “guard[s] against aggressive interpretations of our authorities”?