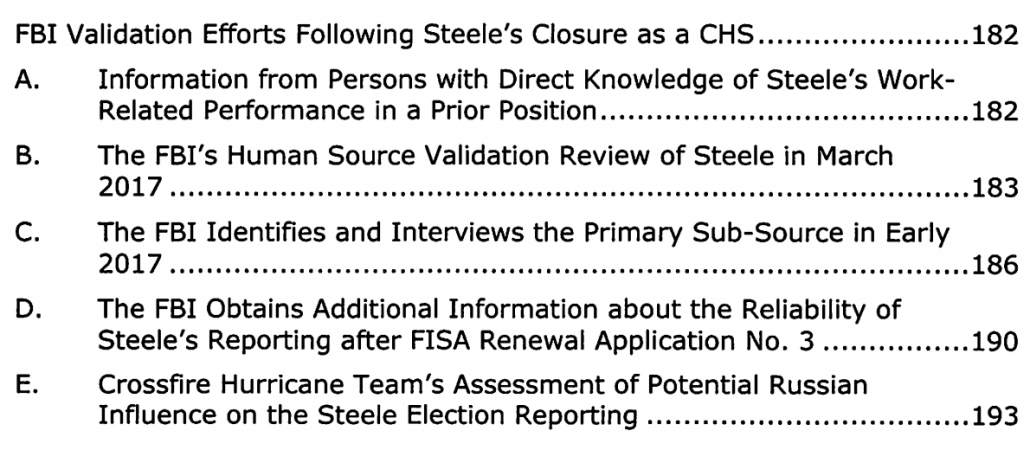

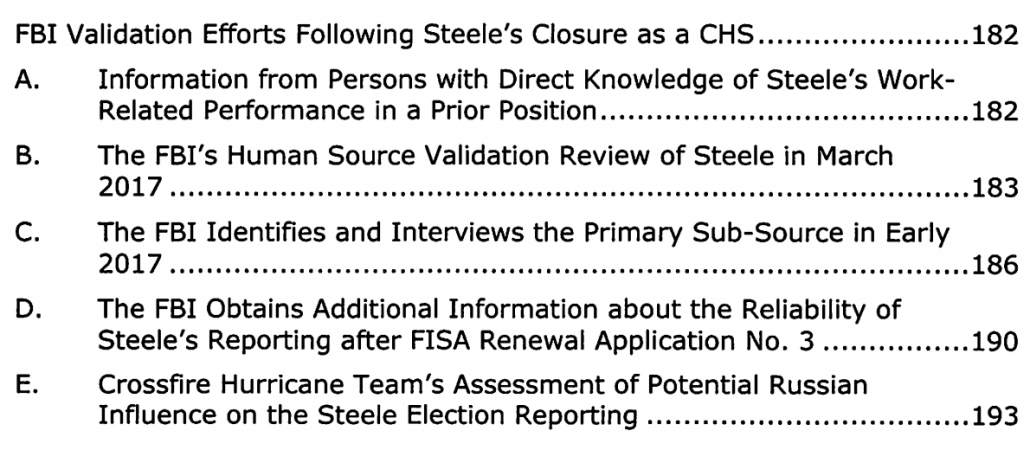

As I said in my summary post, the DOJ IG Report on Carter Page shows there were three problems with the Carter Page FISA application:

- It did not reveal that the first of several attempted recruitments of Page by Russia happened when he was approved for contact by the CIA

- It failed to update the application as questions about the Steele dossier’s reliability became known over time

- It did not include exculpatory evidence (though the report overstates whether information related to George Papadopoulos was exculpatory or the opposite)

On that level, the report is an important portrayal of the FISA application process.

But, as I hope to show generally in a follow-up, the report commits precisely the kinds of errors that it takes the FBI to task for. And in the case of its treatment of Bruce Ohr, the report not only commits those types of errors, but does so in a way that risks harming national security. The Report basically suggests Ohr should be punished for doing what DOJ has spent the last 17 years demanding everyone do: share information related to national security.

Since 9/11, DOJ has emphasized sharing information relating to national security

Ever since 9/11, all parts of the government — especially DOJ and FBI — have concluded over and over again that they have to find ways to better share information relating to national security. 9/11 happened, in part, because CIA didn’t tell FBI that suspected al Qaeda figures had entered the US and, in part, because FBI’s Minnesota field office didn’t tell others about a suspect trying to learn to take off but not land planes. We went to war in Iraq on a mistaken premise because information got stovepiped, rather than shared with people who could appropriately vet it. Nidal Hassan was permitted to remain in the military and so kill 13 people because the FBI’s surveillance systems did not flag his prior contacts with Anwar al-Awlaki. Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab managed to board a plane and try to blow it up because a warning his father had given US authorities didn’t get entered into the flight screener. The FBI missed an opportunity to prevent the Boston Marathon bombing because warnings from Russia and Tamerlan’s travels didn’t get triggered for full investigation.

The emphasis on information sharing is not limited to terrorism. The government’s approach to cybersecurity, too, has focused on better sharing information among different parts of government and with the private sector. Indeed, in this case, the Democrats (not entirely credibly) claimed the FBI didn’t warn them aggressively enough of ongoing hacks and states (far more credibly) complained they didn’t get notice that Russia was targeting voting infrastructure.

DOJ’s Inspector General has repeatedly emphasized information sharing. Just during 2019, DOJ Inspector General Michael Horowitz’s office has released a number of reports calling for more information sharing. On December 20, multiple relevant Inspectors General submitted an assessment mandated by Congress on whether agencies are sharing cybersecurity threat information among themselves and with the private sector; it described continued barriers to sharing such information. On August 1, DOJ IG issued a report calling, in part, for better information sharing between the FBI and Homeland Security Investigations on the border with Mexico. On April 1, DOJ IG issued a report describing some of the impediments to informing victims when they’ve been targeted in a cyberattack, which may delay the victim’s ability to respond. On March 21, DOJ IG issued a report concluding, in part, that FBI Agents conducting assessments about whether terrorists might exploit maritime facilities need to gather better data.

Some of the key reports Horowitz has overseen historically also criticized inadequate information sharing. In March 2018, DOJ IG explained that the FBI gave Congress misleading information about Syed Rizwan Farook’s phone because people weren’t communicating internally about resources available to the Bureau. A September 2017 Report on whether there were known or suspected terrorists in FBI’s witness protection program complained that earlier information sharing recommendations had not yet been implemented. A March 2014 report on DOJ’s efforts to combat mortgage fraud found serious data integrity and collection issues. An October 2013 review of FBI’s responses to being badly burned by Chinese double agent Katrina Leung found the FBI needed to do better tracking and sharing of derogatory information from confidential human sources, a finding pertinent to this report. The September 2012 Fast and Furious report (largely completed prior to Horowitz’s arrival, but released just after he started) emphasized ATF’s inadequate information sharing with DEA and ICE.

None of these conclusions say, “share information, but only after it’s vetted.” DOJ’s Inspector General generally only complains about Department employees sharing information if it involves the sharing of investigative, classified, or sensitive information to unauthorized recipients (including but not limited to the media) or the improper use of whistleblower complaints to retaliate against them.

Ohr did neither of those things.

Indeed, this report is largely about FBI’s failure to share information. There’s even a complaint in there about the over two months it took for Christopher Steele’s first reports to get shared with FBI HQ.

FBI officials we interviewed told us that the length of time it took for Steele’s election reporting to reach FBI Headquarters was excessive and that the reports should have been sent promptly after their receipt by the Legat. Members of the Crossfire Hurricane team told us that their assessment of the Steele election reporting could have started much earlier if the reporting had been made available to them.

One of the three main complaints about FBI’s actions involves their failure to vet the dossier and share the results of that vetting in timely fashion. Along with State Department’s Kathleen Kavalec (whose feedback FBI failed to obtain for over a month), Ohr provided the best timely and accurate details about how the dossier fit into Fusion GPS’s election year process. But one of just nine recommendations DOJ’s IG made in this report is that DOJ’s Office of Professional Responsibility and DOJ’s Criminal Division review his actions.

The Department’s Office of Professional Responsibility should review our findings related to the conduct of Department attorney Bruce Ohr for any action it deems appropriate. Ohr’s current supervisors in CRM should also review our findings related to Ohr’s performance for any action they deem appropriate.

In short, DOJ’s IG has spent years saying “share more information, share more information, share more information.” Bruce Ohr did just that. In response, DOJ IG insinuated he should be fired for it.

Not only does this response undercut every single exhortation to share national security information since 9/11, but it bears similarities to other efforts by DOJ IG to help President Trump retaliate against his critics.

The IG Report misrepresents the nature of Bruce Ohr’s information sharing

The DOJ IG manages to attack a guy for doing what DOJ IG has repeatedly said people should do, share information, by obscuring the nature of his sharing.

While the IG Office declined to provide an on the record answer to a question not answered in the IG Report itself — why Ohr even came to be the subject of this investigation — the answer is clear: When Congress started nagging Rod Rosenstein about their conspiracy theories about Ohr, claiming that Ohr kept injecting the dossier back into the FBI to sustain an investigation into Trump, Rosenstein got the IG to expand the inquiry to include Ohr. The IG Report’s presentation of Ohr’s actions must be taken against the backdrop of what started it: Rosenstein’s capitulation to politicized claims that someone in his office was responsible for pushing the Steele dossier and therefore the investigation into Trump.

The IG Report never does for Ohr’s conversations what it does with Operation Crossfire as a whole (though the facts it presents merit it) — debunk the conspiracy theory about the role of the dossier in predicating the investigation. It leaves out or downplays some key facts. And its narrative does not fit the actual facts it presents about Ohr’s actions.

The facts it does present show:

- Ohr and Steele had been sharing information of mutual interest for years as part of Ohr’s efforts to bring an information-sharing approach to combatting organized crime, including Russian organized crime

- They were sharing information unrelated to the dossier specifically or Trump generally prior to and during their July 30, 2016 meeting

- The report includes no evidence Ohr shared two allegations from the dossier learned at a July 30 meeting with anyone involved in opening Crossfire Hurricane before the investigation got opened

- Steele continued to share information with Ohr that did not appear in the dossier (but that, because it involved credulity about Oleg Deripaska’s willingness to help the US government, was problematic for entirely different reasons)

- Some information Ohr shared from Glenn Simpson was information the FBI otherwise pursued on its own

- During the weeks after FBI closed Steele as a source, Ohr provided some of the most useful information to vet the dossier and the FBI regarded that information as part of the vetting process

- The only time Ohr shared reports from the dossier directly with the Crossfire Hurricane team came during and was regarded as useful because it was part of this vetting process

- The IG Report provides no evidence that Ohr pushed Steele’s Trump-related intelligence in 2017 (even though Steele was working with Dan Jones to continue to collect it)

- The 2017 conversations Ohr had with Steele about the Trump investigation pertained either to protecting sources — something DOJ treated as a priority even in this Report — or to Steele’s concerns about the consequences of the various ongoing investigations on him and his sources

- As he had for years, including in 2016, Steele shared information about other topics with Ohr in 2017, proving that this was not an exclusively Trump-focused effort

- The complaints that Ohr didn’t inform his superiors about this sharing, while justified, are overstated

As noted, there are still problems with what Ohr did in 2016-2017, largely because he and Steele were being used by someone who — lots of evidence suggests — had a role in the 2016 operation, Oleg Deripaska. I plan to do a separate post on what the IG Report says about Deripaska, but the short version is Ohr and Steele’s coziness with him posed real counterintelligence risks. With a few exceptions, it appears that FBI limited the impact of those risks. And that counterintelligence risk is part of the downside of a call to share information widely, but not something unique to Ohr’s actions.

Steele and Ohr had been sharing information as part of their common pursuit against Russian organized crime for years

The IG Report splits up its introduction to how Steele came to work with FBI from its introduction of Ohr’s relationship with him. That means key details about Ohr’s career appear almost 200 pages after the IG Report’s first explanation of how Ohr introduced Steele to his handling agent, Mike Gaeta, described as Handling Agent 1.

In the later section, the IG Report explains Ohr’s background in prosecuting organized crime — including Russian organized crime — and how he moved into more of a policy role on the topic, including leading an Obama initiative to pursue transnational organized crime using an intelligence-based approach similar to the one used to fight terrorism (that is, one based on information sharing). That initiative included a focus on Russian organized crime from the start, and Ohr continued to share information on the topic.

Ohr told the OIG that as Chief of OCRS, he tried to develop the Department’s capacity for fighting transnational organized crime and that this was when he began tracking Russian organized crime.

[snip]

He stated that he was often the Department’s “public face” at conferences and was sometimes approached by individuals who provided information about transnational organized crime.

[snip]

Ohr told us that when he became the OCDETF Director, then DAG Jim Cole expressed his desire for Ohr to expand OCDETF’s mission to include transnational organized crime matters. He said that, as a result, he continued working on transnational organized crime policy and, in order to maintain awareness, tracked Russian organized crime issues.

That later section also describes how Ohr, who had been passing on information from Steele already, came to encourage FBI to open a direct channel with the former MI6 officer for investigative purposes while he continued to accept information from Steele for his own policy purposes.

Ohr said he introduced Steele to Handling Agent 1 so that Steele could provide information directly to the FBI in approximately spring 2010. 407 He told us that he “pushed” to make Steele an FBI Confidential Human Source (CHS) because Steele’s information was valuable. Ohr also said that it was “not efficient” for him to pass Steele’s information to the FBI and he preferred having Steele work directly with an FBI agent. According to Steele, Ohr and Handling Agent 1 coordinated over a period of time with Steele to set up his relationship with the FBI.

Ohr’s contact with Steele did not end after Steele formalized his relationship with Handling Agent 1 and the FBI.408 Ohr met or talked with Steele multiple times from 2014 through fall 2016, and on occasion those in-person meetings or video calls included Handling Agent 1. Ohr told us that he viewed meeting with Steele as part of his job because he needed to maintain awareness of Russian organized crime activities and Steele knew Russian organized crime trends better than anyone else. He said he knew Steele was also speaking to Handling Agent 1 at this time because Steele would say that he provided the same information to Handling Agent 1. Handling Agent 1 told us that he knew Steele and Ohr were in contact and talked about issues “at a higher policy level,” but stated that he did not know anything further regarding their interactions.

Here’s how the more general introduction of Ohr’s introduction of Steele to Gaeta appears without that context, almost 200 pages earlier:

Steele’s introduction in 2010 to the FBI agent who later became Steele’s primary handling agent (Handling Agent 1) was facilitated by Department attorney Bruce Ohr, who was then Chief of the Organized Crime and Racketeering Section in the Department’s Criminal Division in Washington, D.C. Ohr told the OIG that he first met Steele in 2007 when he attended a meeting hosted by a foreign government during which Steele addressed the threat posed by Russian organized crime. Ohr said that, after this first meeting with Steele, he probably met with him less than once a year, and after Steele opened his consulting firm, Orbis Business Intelligence, he furnished Ohr with reports produced by Orbis for its commercial clients that he thought may be of interest to the U.S. government. Ohr said that he eventually put Steele in contact with Handling Agent 1, with whom Ohr had previously worked.

By splitting these two discussions, the IG Report also splits the discussion of the centrality of Steele’s intelligence on Russian oligarchs from the discussion of Ohr’s conversations with Steele in 2016. For example, the FBI formally entered into a source relationship with Steele in 2013 after he shared a report on a fugitive Russian oligarch that proved really valuable.

For example, we learned that, in October 2013, Steele provided lengthy and detailed reports to the FBI on three Russian oligarchs, one of whom was among the FBI’s most wanted fugitives. According to an FBI document, an analyst who reviewed Steele’s reporting on this fugitive found the reporting “extremely valuable and informative” and determined it was corroborated by other information that the FBI had obtained.

The earlier discussion explains how Ohr remained personally involved with Steele in this period, including meeting with Oleg Deripaska (described as Russian Oligarch 1).

Handling Agent 1 told the OIG that Steele facilitated meetings in a European city that included Handling Agent 1, Ohr, an attorney of Russian Oligarch 1, and a representative of another Russian oligarch. 209 Russian Oligarch 1 subsequently met with Ohr as well as other representatives of the U.S. government at a different location. Ohr told the OIG that, based on information that Steele told him about Russian Oligarch 1, such as when Russian Oligarch 1 would be visiting the United States or applying for a visa, and based on Steele at times seeming to be speaking on Russian Oligarch 1’s behalf, Ohr said he had the impression that Russian Oligarch 1 was a client of Steele. 210

Note, the IG Report rather dishonestly either redacts or does not include the dates of these interactions involving Deripaska. Those interactions continued into 2016, and indeed, are — for better and worse — inseparable from any conversations they had about Steele’s work for Fusion.

In addition to providing information on Russian oligarchs that FBI found valuable, Steele also provided information on other topics, including on hacking and Russia’s sports doping.

Steele’s prior reporting to the FBI addressed issues other than Russian oligarchs. For example, we reviewed FBI records reflecting that he provided information on the hack of computer systems of an international corporation, and corruption involving former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych. In addition, Steele told us he introduced Handling Agent 1 to sources with knowledge of Russian athletic doping and obtained samples of material for the FBI to analyze.

As a result, FBI paid Steele $64,000 in 2014 and 2015 and — it doesn’t say this explicitly but the math suggests — $31,000 for information in 2016, none of it for information related to the dossier.

As a result, in 2014 and 2015, the FBI made five payments to Steele totaling $64,000. By the time the FBI closed Steele in November 2016, his cumulative compensation totaled $95,000, including reimbursement for expenses.

All of these topics, of course — Russian oligarchs, Russian doping, and Russian hacking — are an integral part of Russian organized crime. All were part of Bruce Ohr’s job in 2016. That’s the kind of information sharing that the IG Report, with its rebuke of Ohr, is saying DOJ shouldn’t do, contrary to what both the IG and DOJ as a whole have been saying for decades.

By suggesting that sharing this kind of information with other experts on the topic merits discipline or firing, as the IG Report does, DOJ IG risks making us less safe.

The IG Report largely ignores Ohr and Steele’s discussions from the first half of 2016

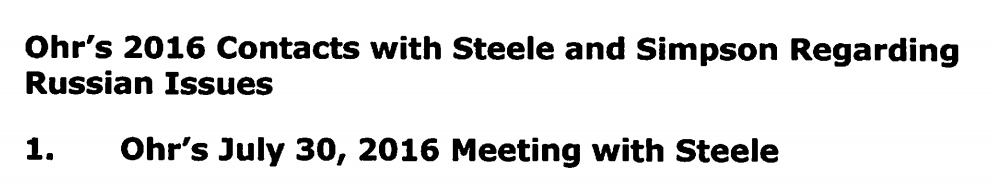

The IG Report then examines what it claims to be Steele and Ohr’s “2016 contacts … regarding Russian issues.” It starts this story with a meeting the two had on July 30, 2016.

Suggesting that Ohr’s July 30, 2016 meeting with Steele is the beginning of the story of contacts they had in 2016 “regarding Russian issues” is profoundly dishonest — the kind of failure to disclose relevant information that the IG Report as a whole condemns the FBI for with regards to Carter Page’s FISA application.

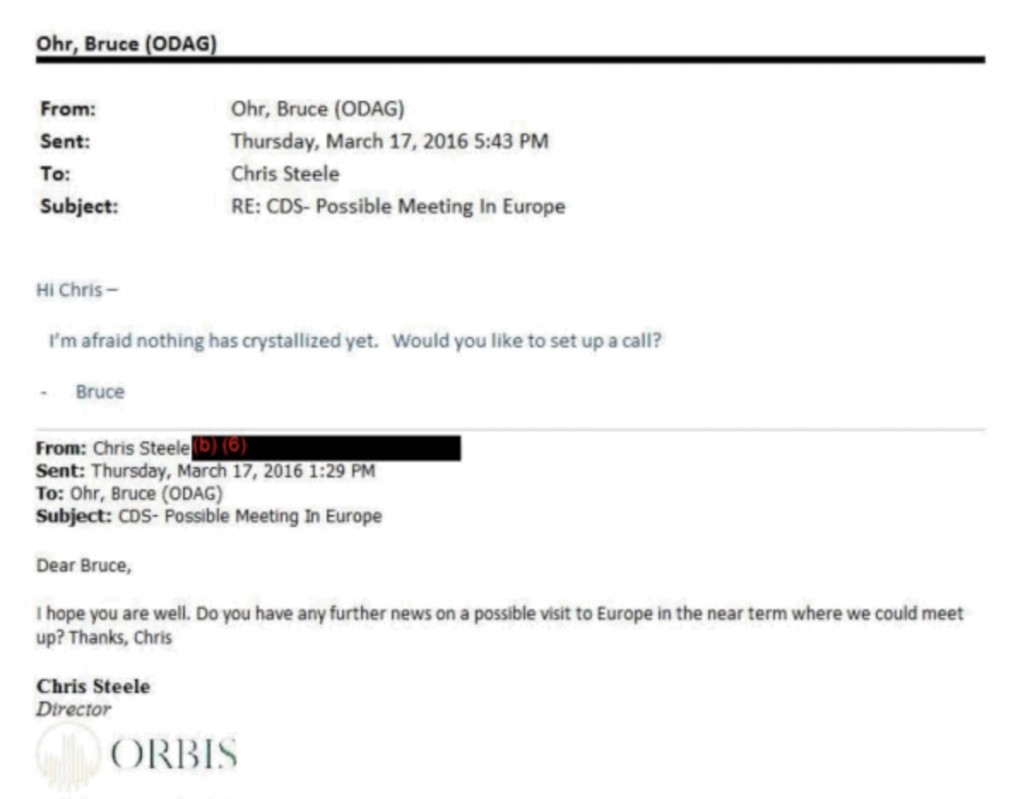

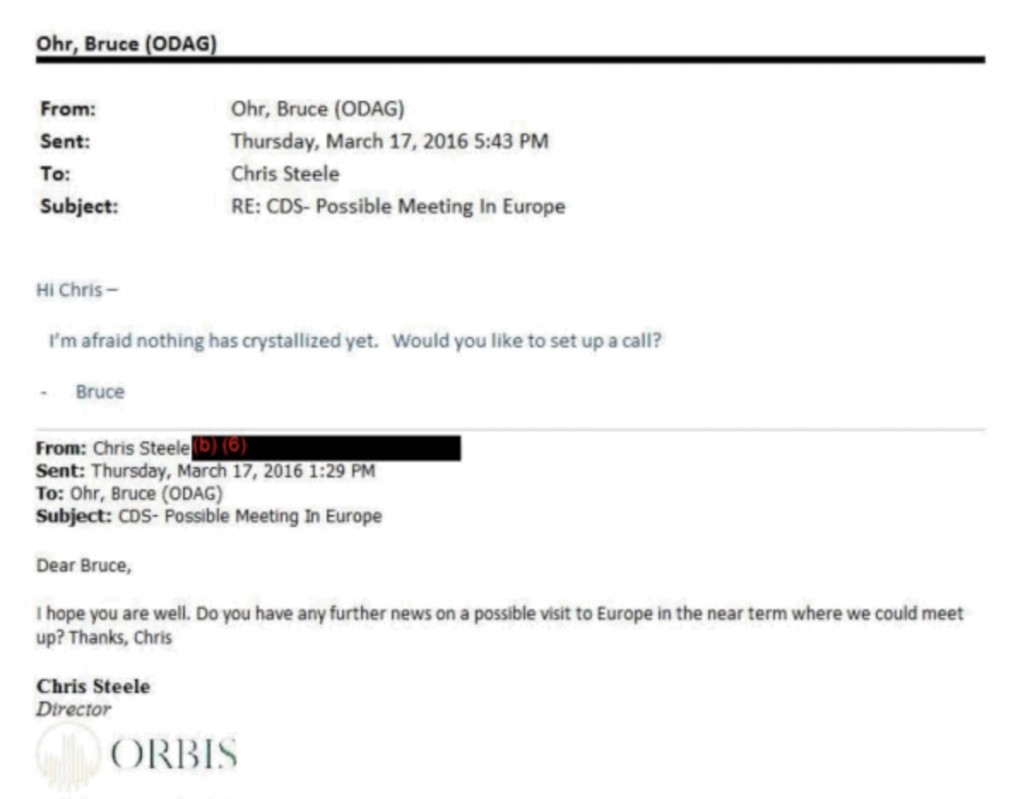

A Judicial Watch FOIA for Ohr’s communications with Steele between January 1, 2015 and December 12, 2017 shows they spoke in March 2016.

In the Judicial Watch FOIA, DOJ redacted the dates on all their other emails in part because of ongoing investigations (suggesting they still had investigative sensitivity at the time DOJ responded to JW’s FOIA), but leaks from Congress to the frothy right made it clear that they also communicated in January, February, and earlier in July. As coverage of those leaks makes clear, the vast majority of their conversations earlier that year include discussion about Deripaska.

The emails, given to Congress by the Justice Department, began on Jan . 12, 2016, when Steele sent Ohr a New Year’s greeting. Steele brought up the case of Russian aluminum magnate Oleg Deripaska (referred to in various emails as both OD and OVD), who was at the time seeking a visa to attend an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting in the United States. Years earlier, the U.S. revoked Deripaska’s visa, reportedly on the basis of suspected involvement with Russian organized crime. Deripaska was close to Paul Manafort, the short-term Trump campaign chairman now on trial for financial crimes, and this year was sanctioned in the wake of Russian involvement in the 2016 presidential election.

“I heard from Adam WALDMAN [a Deripaska lawyer/lobbyist] yesterday that OD is applying for another official US visa ice [sic] APEC business at the end of February,” Steele wrote in the Jan . 12 email. Steele said Deripaska was being “encouraged by the Agency guys who told Adam that the USG [United States Government] stance on [Deripaska] is softening.” Steele concluded: “A positive development it seems.”

Steele also asked Ohr when he might be coming to London, or somewhere in Europe, “as I would be keen to meet up here and talk business.” Ohr replied warmly the same day and said he would likely travel to Europe, but not the U .K ., at least twice in February.

An early July exchange includes the reference to a “favorite business tycoon” that the frothy right would — falsely — spin up into an early reference to Trump (it was another reference to Deripaska).

Then, on July 1, came the first apparent reference to Donald Trump, then preparing to accept the Republican nomination for president. “I am seeing [redacted] in London next week to discuss ongoing business,” Steele wrote to Ohr, “but there is something separate I wanted to discuss with you informally and separately. It concerns our favourite business tycoon!” Steele said he had planned to come to the U.S. soon, but now it looked like it would not be until August. He needed to talk in the next few days, he said, and suggested getting together by Skype before he left on holiday. Ohr suggested talking on July 7. Steele agreed.

Both of these passages, even with the error imagining a Deripaska reference invokes Trump, include discussion (bolded in both) about what appears to be other business. Yes, the reference in the IG Report explaining that Ohr thought Steele might be working for Deripaska, appearing 180 pages earlier, probably incorporates these references. But their earlier 2016 contacts — both about Deripaska (and therefore Russia) and other business — provide important context for the discussion of the July 30 meeting, which IG Report falsely suggests is the beginning of the discussions about Russia they had been happening since the beginning of the year. Not least, because those earlier contacts not only make it clear that their relationship did not shift radically when Steele started working on the dossier, but they also make it clear that Steele and Ohr’s contacts about Deripaska — however problematic — would not appear to be a break from their previous three year focus on Deripaska and other oligarchs.

Having ignored earlier conversations about other topics in 2016, the Report then provides this description of the first meeting where they did speak about Trump.

On Saturday, July 30, 2016, at Steele’s invitation, Ohr and Nellie Ohr had breakfast with Steele and an associate in Washington, D.C. Nellie Ohr told us she initially thought it was going to be a social brunch, but came to understand that Steele wanted to share his current Russia reporting with Ohr. According to Steele, he intended the gathering to be a social brunch, but Ohr asked him what he was working on. Steele told us that he told Ohr about his work related to Russian interference with the election. Ohr told us that, among other things, Steele discussed Carter Page’s travel to Russia and interactions with Russian officials. He also said that Steele told Ohr that Russian Oligarch 1 ‘s attorney was gathering evidence that Paul Manafort stole money from Russian Oligarch 1. Ohr also stated that Steele told him that Russian officials were claiming to have Trump “over a barrel.” According to Ohr, Steele mentioned that he provided two reports concerning these topics to Handling Agent 1 and that Simpson, who owned Fusion GPS, had all of Steele’s reports relating to the election. Steele did not provide Ohr with copies of any of these reports at this time. Later that evening, Steele wrote to Ohr asking to “keep in touch on the substantive issues” and advised Ohr that Simpson was available to speak with him. [my emphasis]

If you didn’t know better, you’d think that on July 30, 2016, Christopher Steele lured Bruce Ohr to brunch to push his dossier and only his dossier.

Except … that would be wrong.

Even leaving out the context of the years during with Steele and Ohr had discussed matters of Russian oligarchs generally and Deripaska specifically, as the IG Report does, Deripaska’s feud with Paul Manafort — while likely crucial background to the dossier — cannot be described as content from the dossier. The only possible reference to the feud in the dossier is a report, dated October 19, referring to “scandals involving MANNAFORT’s [sic] commercial and political role in Russia/Ukraine.” If the Deripaska feud were to be treated as part of the dossier, then so should be Deripaska’s outreach to Manafort on August 2, 2016, one of the most suspect unexplained events from 2016 (as I’ll show in a follow-up, this is a critical overlap, but one that points to other problems the IG Report barely mentions).

Even leaving out the context of the years during with Steele and Ohr had discussed matters of Russian oligarchs generally and Deripaska specifically, as the IG Report does, Deripaska’s feud with Paul Manafort — while likely crucial background to the dossier — cannot be described as content from the dossier. The only possible reference to the feud in the dossier is a report, dated October 19, referring to “scandals involving MANNAFORT’s [sic] commercial and political role in Russia/Ukraine.” If the Deripaska feud were to be treated as part of the dossier, then so should be Deripaska’s outreach to Manafort on August 2, 2016, one of the most suspect unexplained events from 2016 (as I’ll show in a follow-up, this is a critical overlap, but one that points to other problems the IG Report barely mentions).

Plus, this passage appears to deliberately obscure behind the phrase “among other things,” the full range of what got discussed. As it appears, the phrase suggests Ohr and Steele discussed, among other things, Carter Page’s alleged trip to Moscow, with the other things being Deripaska’s feud with Manafort and Russia’s claim to have Trump “over a barrel.” This passage suggests those are the only three topics discussed.

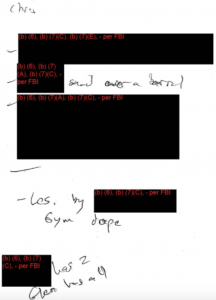

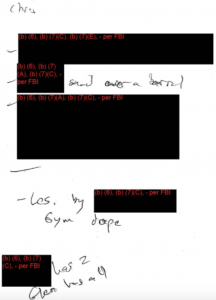

But that’s false. As Ohr’s own notes and testimony make clear, in between the time he discussed Page and Russia having Trump over a barrel and Manafort’s dispute with Deripaska and when he told Ohr that Steele’s handling agent, Mike Gaeta, had two reports on this and Glenn Simpson had four, Steele discussed something about Russian doping.

Q Were there any other topics that were discussed during your July 30, 2016, meeting?

A Yes, there were. Based on my sketchy notes from the time, I think there was some information relating to the Russian doping scandal, but I don’t recall the substance of that. And based on my notes, it indicated that Chris Steele had provided some reports to the FBI, I think two, but that Glenn Simpson had more.

In other words, in addition to information about the Deripaska feud that doesn’t appear in the dossier, Steele also shared information on Russian doping, information on Russia that had nothing to do with Trump.

In other words, what appears to have happened is that Steele and Ohr had a meeting that, in significant part, reflected a continuation of their past discussions, especially regarding Deripaska, but also Russian doping, both key parts of Ohr’s work on organized crime. Along with that, Steele shared two details that showed up in some form in dossier reports. And Ohr seems to have treated that the way he treated other information he got from Steele. He shared it with Gaeta (who already had received the dossier-related information) and Deputy Assistant Attorney General for International Affairs Bruce Swartz (who had been concerned about Manafort’s corruption for several years). DOJ IG found no evidence he shared it with the people who opened Crossfire Hurricane and therefore no evidence that the dossier was part of the reason they opened the investigation.

Then, Ohr spoke with or met Steele or Glenn Simpson four more times before the election. According to the IG Report’s own descriptions, those four additional times Ohr shared information related to Steele before the election, it was often tangential to matters in the dossier, rather than the key allegations in it.

On August 22, for example, Ohr met with Glenn Simpson, who shared the names of three people who he thought might be intermediaries between Trump and Russia. The two of those that are public — Sergei Millian and (by description) probably Sergey Yatsenko — were of interest in the Mueller Report. In fact, Millian was already on the FBI’s radar, and in October 2016, FBI would open a counterintelligence investigation into him. According to the IG Report, Ohr probably shared that information with Gaeta and maybe with FBI’s Transnational Organized Crime people.

Then, on September 23, Ohr met Steele. They discussed who was funding Fusion GPS’s opposition research, allegations about the Alfa Bank/Trump Tower server, including a claim that Millian also used the Alfa Bank server, and that an individual working with Carter Page was a Russian intelligence officer. None of these topics show up in Steele’s publicly released dossier reports, though FBI obtained three reports that are not public. Steele would explain to DOJ IG that Orbis was not responsible for the Alfa Bank allegations, though would do a report on the relationship Alfa’s founders had with Putin from years earlier. According to the IG Report, Ohr probably shared this information with Bruce Swartz and possibly Gaeta.

On October 13, FBI’s Transnational Organized Crime-East people told Ohr (probably in response to a question from him) that counterintelligence agents had spoken with Gaeta; Ohr told them he had the names of three possible intermediaries, one of whom (Millian) FBI had either just or was about to open an investigation into. The IG Report is inconclusive about whether this conversation went any further.

Early on October 18, Steele contacted Ohr about Oleg Deripaska’s company, Rusal, being sanctioned (probably in Ukraine). Shortly thereafter, Ohr scheduled a meeting to discuss Steele’s information with Andrew McCabe, with whom he had worked on organized crime in the past. According to Lisa Page’s notes from the meeting, they discussed Steele’s background, Nellie Ohr’s by then past relationship with Fusion (her last day was September 24), and the three intermediaries Simpson was concerned about. They also talked about Deripaska.

Lisa Page’s notes from the meeting show that Ohr discussed Steele, provided Steele’s previous employment background, talked about issues concerning Russian Oligarch 1, and indicated that Simpson provided Ohr with names of intermediaries between the Kremlin and the Trump campaign. Lisa Page also wrote that Ohr met with Russian Oligarch 1 the previous year and “Need report?”

DOJ IG was clearly skeptical of Ohr’s decision to set up this meeting after having been told, five days earlier, that counterintelligence agents were meeting with Gaeta. But there’s an explanation that would be bloody obvious if the Report hadn’t downplayed the continuity in Ohr and Steele’s discussions about Deripaska but instead treated all the information coming in from Steele as dossier-related information. This was, according to the description in the IG Report, a meeting significantly focused on Deripaska (which makes sense, given that’s what Steele called Ohr that morning about).

Deripaska was treated at the time less as a counterintelligence issue and more as a witness to Manafort’s corruption. Probably, this was Deripaska’s effort to work both sides, offering to provide dirt on Manafort in exchange for some protection against US sanctions (which makes the reference to “scandals involving MANNAFORT’s [sic] commercial and political role in Russia/Ukraine” in a Steele report the next day all the more provocative). Again, Ohr’s involvement in a Deripaska channel deserves far more attention, but of the kind that the IG Report only gives a passing mention to. But it’s an obvious explanation for why Ohr would schedule this meeting in the wake of discussing increasing pressure on Deripaska’s company.

In any case, at the meeting, per both McCabe and Ohr, Ohr provided information that was treated as derogatory information against Steele: that Nellie had worked with Simpson, that he was sharing his information with a number of others, and that he was collecting the information as opposition research. This is the kind of information the IG Report, generally, complains wasn’t shared widely enough. And yet it faults Ohr for sharing it.

Immediately after Mother Jones published an article demonstrably based on Steele’s reporting, the FBI closed him as a source. Up until that point, Ohr had shared:

- The Carter Page allegation and a general allegation about Trump that might reflect the pee tape report

- Information (however problematic from a counterintelligence standpoint) about Oleg Deripaska that showed up in the dossier in passing if at all

- Information about another Russia-related topic, doping

- Three names that Glenn Simpson thought might be intermediaries between Trump and Russia, two of whom FBI agreed were suspect

- Allegations about Alfa Bank that Steele claims did not come from Orbis

- What the IG Report treats as the kind of derogatory information it wishes FBI had obtained earlier

In short, the IG Report does not support two key conspiracy theories about Ohr’s role — that he introduced the Crossfire Hurricane team to the dossier before they opened the investigation into Trump, and that his information sharing amounted to an effort to push the dossier to the FBI (though he definitely believed Trump’s close ties to Russia merited scrutiny, and kept pushing the names of intermediaries the FBI seems to have considered concerning themselves). Nevertheless, the IG Report seems to treat Ohr’s information sharing as if those conspiracy theories were true.

The IG Report demands that FBI treat information from Ohr as vetting information but doesn’t give Ohr credit for helping FBI to vet the dossier

During the month from November 21 to December 20, Ohr had a series of meetings with the Crossfire Hurricane team or a Supervisory Agent from it (SSA 1) in which he provided extensive information about Steele, the dossier, Glenn Simpson, and his wife Nellie’s work for Simpson (most of which, by time and apparent volume, was paid for by right wing billionaire Paul Singer).

The IG Report makes it clear that the Crossfire Hurricane team treated the first of these meetings, on November 21, as part of their vetting process

Strzok, the OGC Unit Chief, SSA 1, and the Intel Section Chief told us the purpose of the meeting was to better understand Steele’s background and reliability as a source and to identify his source network.

Members of the team believed some of what Ohr shared in the following weeks might be helpful in the vetting process, too. Bill Priestap, FBI’s Counterintelligence Assistant Director, who was overseeing the investigation, described Ohr’s ties with Steele as potentially useful as a way to better understand the dossier.

Priestap stated that the FBI’s engagement with Ohr to learn what Steele had shared with Ohr was potentially useful in understanding Steele and verifying his reporting.

The agent he had follow-up meetings with found Ohr’s background helpful and though Ohr might be able to help him identify Steele’s source network (how the FBI succeeded in identifying Steele’s source network remains unexplained in the IG Report).

SSA 1 stated that he was in “receive mode” with respect to Ohr’s information and was trying to glean from it as much as he could about Steele’s source network. He also said that Ohr was well-versed in Russian organized crime and that, in SSA 1’s view, Ohr’s motives for coming to the FBI were “pure.”

The Supervisory Analyst involved with the investigation told the IG that “the Simpson thumb drive containing some of Steele’s reports the FBI did not already possess [was] an example of useful information from Ohr.”

There’s no evidence in the IG Report that Ohr attempted to protect Steele during this vetting process. Indeed, the IG Report focuses on a number of the potentially derogatory things Ohr says about Steele’s actions or his reporting.

- Because of the impact of the dossier-based David Corn article, Ohr apologized to Gaeta for even introducing him to Steele

- Ohr told Kathleen Kavalec (before or after a meeting on how to respond to Russian efforts to influence foreign elections) that Steele’s information was “kind of crazy”

- Ohr warned the Crossfire Hurricane team that reporting of Kremlin activities “may be exaggerated or conspiracy theory talk,” so Steele cannot know whether all the reporting is true

- Ohr revealed that Steele was “desperate” that Trump not be elected, but was providing reports for ideological reasons, specifically that “Russia [was] bad”(while notes from the meeting made it clear Ohr described this as ideological, the 302 of that meeting did not reflect that, which has formed a key sound bite to undermine Steele)

And in fact, a failure to integrate Ohr’s candid comments about Steele and the Fusion project — starting at least in October — make up two of the IG Report’s 17 complaints about the FBI’s actions.

11. Omitted information obtained from Ohr about Steele and his election reporting, including that (1) Steele’s reporting was going to Clinton’s presidential campaign and others, (2) Simpson was paying Steele to discuss his reporting with the media, and (3) Steele was “desperate that Donald Trump not get elected and was passionate about him not being the U.S. President”

12. Failed to update the description of Steele after information became known to the Crossfire Hurricane team, from Ohr and others, that provided greater clarity on the political origins and connections of Steele’s reporting, including that Simpson was hired by someone associated with the Democratic Party and/or the DNC;

Yet, even though the IG Report makes it clear the team treated these discussions as useful for vetting, and even though the IG Report criticizes the FBI for not including derogatory information Ohr provided in the Carter Page FISA applications, the IG Report does not treat these exchanges (or comments from State Department’s Kathleen Kavalec) as part of the vetting process, which it covered 80 pages earlier in the IG Report.

Effectively, then, DOJ IG advocates punishing Ohr for the most timely vetting of the dossier, including the details about Steele’s efforts to share it with the press.

DOJ IG protects sources while complaining that Steele attempted to protect his sources

The final period of Ohr’s communications with Steele covered by the IG Report spans from January 25 through November 2017. As I lay out in this post based on the underlying notes and FBI 302s, those communications largely consist of Steele panicking about the possibility his source will become exposed and require help, followed by Steele’s concern about the impact of ongoing investigations on him or his sources. There’s no mention — in the 302s, the IG Report, or the underlying notes — of Steele sharing any details of his ongoing intelligence collection into Trump, though there continue to be references to Deripaska.

Given that even Bill Barr’s DOJ kept all Steele’s identified sources (even Oleg Deripaska and Sergei Millian) anonymous and the earlier release of the 302s and his notes use the FOIA exemption designated for source protection, DOJ clearly agrees with the import of protecting his sources, so it’s hard to understand how this could be an improper conversation (even if you can be exasperated with Steele’s panic given that he himself was sharing his own raw intelligence with the press).

Moreover, as the IG Report admits far more forthrightly for this period than it did their earlier conversations, to the extent that Steele was sharing his intelligence reporting in 2017, it didn’t have to do with Trump.

In addition to the information summarized in this section, Ohr also provided information to the FBI from Steele and other individuals on unrelated matters.

[snip]

On February 14, 2017, Ohr shared with SSA 3 and Case Agent 8 information on topics Steele was working on for different clients, unrelated to Russia or Crossfire Hurricane.

[snip]

SSA 3 also told us that Ohr forwarded other information to the team regarding Russian oligarchs and other issues unrelated to the Crossfire Hurricane investigation.

Some of these conversations were ill-considered (such as the Deripaska ones, as well as an effort by the lawyer that represented both Julian Assange and Deripaska to trade Assange immunity for advance notice of the Vault 7 files). But the IG Report provides no indication that they were outside the norm for Ohr or detrimental to Trump.

The IG Report also makes it clear that, even though Steele was likely trying to get Ohr to help his clients, it never found evidence he did so. DOJ didn’t find any instance of it.

Ohr said that he understood Steele was “angling” for Ohr to assist him with his clients’ issues. For example, Ohr stated that Steele was hoping that Ohr would intercede on his behalf with the Department attorney handling a matter involving a European company. Ohr denied providing any assistance to Steele in this regard, and we found no evidence that he did.

Nor did the FBI.

The FBI personnel we interviewed generally told us that Ohr did not make any requests of the FBI, nor did he inquire about any ongoing cases or make any recommendations about potential investigative steps.

DOJ IG’s analysis of Ohr’s actions strains to reach a negative conclusion

Which brings us to the basis of the IG’s complaint about Ohr’s information sharing. The complaint is twofold. First, some people claimed that Ohr was doing stuff that was not part of his job. The most credible of those complaints came from the Transnational Organized Crime-East Section Chief, who complained Ohr should have just handed off Steele entirely to the FBI (though Ohr’s direct meeting with Oleg Deripaska happened with an FBI Agent).

The TOC-East Section Chief noted that while it was odd to have a high-level Department official in contact with Russian oligarchs, it did not surprise him that Ohr would be approached by individuals, such as Steele, who wanted to talk to the U.S. government. The TOC-East Section Chief said that it would be “outside [of Ohr’s] lane” to continue the relationship with these potential sources after their introduction to the FBI.

Steele’s handler, Mike Gaeta, knew that Ohr continued his contacts with Steele, even if he didn’t know the substance of them. And one of the Steele emails to Ohr the IG Report does not include in the report shows that Steele also knew his intelligence had to go through Gaeta.

Steele said he would send the reporting to a name that is redacted in the email, “as he has asked, for legal reasons I understand, for all such reporting be filtered through him (to you at DoJ and others).”

That’s consistent with the fact that Steele did not provide any of his reports directly to Ohr; only Simpson did that, during the period the FBI was vetting the dossier.

Meanwhile, contrary to the claims that Ohr was working outside his lane, the State Department believed he was an appropriate attendee for a meeting focusing on Russia’s interference in other countries’ elections.

On the morning of November 21, 2016, at the State Department’s request, Ohr met with Deputy Assistant Secretary Kathleen Kavalec and several other senior State Department officials regarding State Department efforts to investigate Russian influence in foreign elections and how the Department of Justice might assist those efforts.

Perhaps the most telling complaint that Ohr was doing something that was not his job came from Sally Yates, in whose office he worked during the most substantive conversations he had with Steele. She was “stunned,” she told the IG investigators, by press reports describing Ohr communicating to Steele about stuff that “involved the Russia investigation.”

Former DAG Yates told the OIG that she was “stunned” to learn through media reports in late 2017 that Ohr had engaged in these activities without telling her, and that she would have expected Ohr to inform her about his communications with Steele because they were outside of his area of responsibility and involved the Russia investigation. Yates added that she “would have hoped that [Ohr and the FBI] would have both told me” of Ohr’s meetings with Steele and the FBI. She further stated that Ohr’s activities needed to be coordinated with the overall Crossfire Hurricane investigation, which included ensuring that the chain of command at both the Department and FBI were jointly deciding what actions, if any, Ohr might take relating to the Russian interference investigation.

The thing is, Yates’ response is clearly a response to the press reporting, which claimed that every communication they had pertained to the Steele dossier and Trump, not the substance of what Ohr was doing — which included communications about Deripaska and Russian doping. This passage suggests that the IG didn’t inform her the depictions of what Ohr was doing in the press were significantly debunked by what IG investigators found. Yates also complained that Ohr should not have had the October 18 meeting with someone as senior as Andrew McCabe without informing her, which is a far more substantial complaint, except one that is inconsistent with her suggestion that Ohr communicated with the Crossfire Hurricane team without coordinating with FBI’s chain of command.

The person leading the Deputy Attorney General’s office (and therefore the Russian investigation once Jeff Sessions recused) after Yates got fired was Dana Boente. The IG Report shows that Boente — along with the entire rest of the chain of command, including Scott Schools, who would later demote Ohr — at least got briefed of his relationship with Steele in the context of the Russian investigation.

As described in Chapter Nine, handwritten notes of an FBI briefing Boente received in February 2017 indicate that the FBI advised Boente and others at that time-including [Stu] Evans, then Acting Assistant Attorney General Mary McCord, then Deputy Assistant Attorney General George Toscas from NSD, ADAG Tashina Gauhar, ADAG Scott Schools, and Principal ADAG James Crowell-that Ohr knew Steele for several years and remained in contact with him, and that Ohr’s wife worked for Simpson as a Russian linguist. However, none of these handwritten notes-which include separate notes taken by Boente, Schools, and Gauhar-stated that the FBI had interviewed Ohr or that Ohr had provided the FBI with information regarding Steele’s election reporting or Steele’s feelings toward candidate Trump. Schools told us that he recalled a meeting in which the OGC Unit Chief referenced Ohr having contact with Simpson, but Schools was not sure if it was during this February 2017 briefing or another briefing. Further, he said that it was a “passing reference,” and he never would have imagined that Ohr was having regular contact with the Crossfire Hurricane team and providing the information that appeared in the FD-302s. Boente and the other attendees of the February 2017 briefing told the OIG that they did not recall the FBI mentioning Ohr at any time during the investigation, and that they did not know about the FBI’s interviews with Ohr at the time of the FISA applications. According to Gauhar, she was surprised to find a reference to Ohr in her notes, and, regardless, she “would never have dreamt” back then what she knows now concerning the extent of Ohr’s interactions with Steele, Simpson, and the FBI on Steele’s election reporting.

The IG Report seems to complain that the FBI did not offer up Ohr’s role robustly enough. But it seems to hold Jim Comey responsible for having received the same level of briefing about Ohr’s actions (which question, in addition, seems to be premised on the public conspiracies about Ohr which may explain why he didn’t believe he had heard about them).

Comey told us he had no knowledge of Ohr’s communications with members of the Crossfire Hurricane investigative team and only discovered Ohr’s association with Steele and the Crossfire Hurricane investigation when the media reported on it. However, notes taken by Strzok during a November 23, 2016 Crossfire Hurricane update meeting attended by Comey, McCabe, Baker, Lisa Page, Anderson, the OGC Unit Chief, the FBI Chief of Staff, and Priestap, reference a discussion at the meeting concerning “strategy for engagement [with Handling Agent 1] and Ohr” regarding Steele’s reporting. Strzok stated that, based on his notes, he believed he informed FBI leadership that Ohr approached the FBI concerning his relationship with Steele and that Ohr relayed Steele’s information regarding Russia to the team. Although the OGC Unit Chief could not recall when it occurred, she recalled discussing with executive leadership that the FBI should not use Ohr to direct Steele’s actions. Because Strzok’s notes of the meeting were classified at the time we interviewed Comey, and Comey chose not to have his security clearances reinstated for his OIG interview, we were unable to show him the notes and ask about the reference in them to Steele and Ohr. [my emphasis]

That’s especially true given that no one was using Ohr to direct Steele’s actions, which seems to suggest that these questions were based, as many of the ones about Ohr, on a false premise arising from the conspiracy theories that the IG Report does not support.

If you ask top managers whether they knew of Ohr’s actions that exist only in conspiracy theories but not in reality, there may be a ready explanation for why they didn’t know about it: because (as the evidence presented in the IG Report makes clear) the conspiracy theories imagined things had happened that had not.

In any case, DOJ IG seems to hold the FBI to a much higher standard for asking questions at briefings, and so doesn’t treat a briefing where the entire chain of command at ODAG and NSD was informed Ohr had a role as informing them he had a role. Scott Schools, who was in that FBI briefing with NSD and was the one who demoted Ohr, complains that FBI didn’t fully report Ohr’s involvement to NSD.

Then Associate Deputy Attorney General Scott Schools, who was the highest-ranking career official in the Department, and ODAG’s ethics advisor, stated that the FBI had a responsibility to fully report Ohr’s involvement to the Department’s National Security Division (NSD) and that Ohr had a duty to report his involvement to ODAG’s managers.

But he also describes a conversation with Ohr where Ohr asked about ethics.

Schools recalled that Ohr, at some point, “stuck his head in the door and said, hey I just wanted to make sure there’s nothing I need to do. My wife works at Fusion GPS. I don’t know if there’s anything, like, a recusal, or anything I need to deal with.” Schools stated that he responded to Ohr by saying that “you don’t have anything to do with that case. We don’t typically in the Department recuse individuals who aren’t responsible for the matter giving rise to a potential conflict.” Schools believed this conversation occurred a couple months before Ohr’s conduct became public and may have coincided with Ohr’s October 2017 conversation with Rosenstein.

If this conversation really did not take place until October 2017, as Schools says, then his understanding of it is inaccurate, as by that point Nellie Ohr had not worked for Fusion for over a year and Ohr had had no role in sharing substantive information about the Russian investigation for ten months. If Ohr really did raise the issue of a conflict because of Nellie’s work, however, it’s much more likely it happened a year earlier, when he was providing the same warnings to FBI.

In any case, Ohr’s question to Schools, whenever it occurred, raises real questions about why DOJ IG included analysis finding that Ohr “displayed a lapse in judgment” for not choosing to use a process that, guidelines say, should not be characterized as a lapse.

The federal ethics rules further provide in Section 502(a)(2) that an employee “who is concerned that circumstances other than those specifically described in this section would raise a question regarding his impartiality should use the process described in this section [namely, to consult with Department ethics officials] to determine whether he should or should not participate in a particular matter.” However, while OGE has made clear that employees are “encouraged” to use this process, it also has stated that “[t]he election not to use that process should not be characterized … as an ‘ethical lapse.”‘ OGE 94 x 10(1), Letter to a Department Acting Secretary, March 30, 1994; see also, OGE 01 x 8 Letter to a Designated Agency Ethics Official, August 23, 2001. While OGE guidance establishes that Ohr did not commit a formal ethical violation, we nevertheless concluded that Ohr, an experienced Department attorney and a member of the SES, should have been more cognizant of the appearance concerns created by Nellie Ohr’s employment with Fusion GPS and availed himself of the process described in Section 502(a). We found that his failure to take this step displayed a lapse in judgment. [my emphasis]

The first step of using the process, it seems, is asking the department ethics advisor if he needed to use the process.

All of which brings us to Rod Rosenstein’s claimed surprise of hearing about Bruce Ohr’s relationship with Steele. Ohr warned Rosenstein that his role in introducing Steele to the FBI when he learned it might become public. Rosenstein didn’t pursue it until Congress started sowing conspiracy theories about it.

He complains, fairly, about the fact that he did not know Ohr had an operational role in the investigation (note, as with all of this, it’s unclear whether Rosenstein knew the actual details of what Ohr had done when, or whether he understood Ohr to have tried to sustain the Steele dossier, as the GOP was alleging).

Ohr told the OIG that in October 2017, Nellie Ohr received a call from someone at Fusion GPS who told her that the company was providing documents to Congress that identified her as a Fusion GPS contractor and that he realized that then DAG Rosenstein may need to know about this, so he asked to speak with him. He stated that he informed Rosenstein that his wife, Nellie Ohr, worked for Fusion GPS, and that it may become public that Ohr knew Steele and introduced him to the FBI. Ohr told the OIG that he was “prepared to go into more detail [with Rosenstein], but there really wasn’t time.” Rosenstein recalled having this conversation in Ohr’s office and told us he remembered Ohr stating he knew Steele and that Nellie Ohr worked for Fusion GPS. Rosenstein told us that during this conversation, Ohr may have also said that he introduced Steele to the FBI and that all this information may become public. Rosenstein described the meeting with Ohr as casual and noted that he was in Ohr’s office for another reason, which indicated to him that Ohr did not make a special effort to notify him. Rosenstein stated that he left the conversation under the impression that it was only a “strange coincidence” that Ohr knew Steele.

[snip]

Ohr told us that a few weeks after his first conversation with Rosenstein on this issue, he spoke with Rosenstein again and told him that he still talked to Steele from time to time and provided information to the FBI when Steele called him. Rosenstein told us that he recalled a second conversation with Ohr concerning Steele, which he believed occurred in early December 2017. According to Rosenstein, Ohr told him that he delivered a thumb drive containing Steele’s election reports to the FBI. Rosenstein said this information changed his perspective of the situation. Rosenstein told us the fact that Ohr

knew Steele was kind of just an unusual coincidence, but the idea that he had actually had some role in this Russia investigation was shocking to me…. [W]e had been fending off these Congressional inquiries. And they were asking for all sorts of stuff, [FD-]302s and things, and .. .l had no idea that somebody on my staff had actually been involved in … an operational way in the investigation.

[snip]

Rosenstein told us Crowell and Schools reported back to him with their findings, and at that point, he realized Congress likely knew more about Ohr’s activities with Steele and the FBI than anyone in ODAG did. Rosenstein told us:

[It] was really disappointing to me that he had made the decision originally not to brief anybody [on] our staff and then even after it was clear it was going to be … of national interest…he chose not to disclose, at least to [Schools], that he had actually had an active role …. I felt like, if you’re in the DAG’s office, and the DAG is getting criticized by Congress for the handling of the Russia investigation, you ought to tell him that you had some role in it.

Again, this is fair enough, though Rosenstein seems to be interpreting Ohr’s effort to inform him in the light that best serves himself.

The truly crazy take from Rosenstein’s office, however, came from Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General James Crowell, who complained about how bad it would be to have a “potential fact witness” on Rosenstein’s staff when he supervised the Russia investigation.

Crowell stated that he was “flabbergasted” when he learned about Ohr’s involvement with Steele and the FBI. He stated that Ohr should have informed ODAG officials of his relationships with Steele and Simpson and his provision of information from them to the FBI, especially when Rosenstein appointed the Special Counsel and began supervising the investigation, because “a potential fact witness” was on Rosenstein’s staff.

Rosenstein’s staff was worried about Ohr because it meant that “a potential fact witness” was on Rosenstein’s staff.

Bruce Ohr’s name shows up once in the Mueller Report, in a quoted August 2018 tweet from Trump, perhaps not unsurprisingly given that he dossier was not central to the Mueller investigation. Rosenstein’s name shows up 78 times.

If Rosenstein and his deputies were worried about potential fact witnesses working in his office while he supervised the investigation, he should have recused himself.

By all means, Ohr should have revealed his role earlier. Most of all, he should have done so to avoid being criticized for things he did not do — like sustaining the dossier with FBI — so we could instead have a conversation about what point sharing information moves from vetting and becomes a counterintelligence risk.

In a follow-up, I hope to compare what DOJ IG did with Ohr and what Andrew McCabe has substantiated in a recent court filing.

But the bigger concern, to me, is that because Rod Rosenstein was embarrassed by conspiracy theories that this IG Report rebuts, DOJ’s Inspector General wrote up a report that villainizes one of the few people in this Report that was doing what DOJ has spent almost two decades trying to get people to do: sharing information on national security in timely fashion. The facts presented in the report don’t support such a stance, and the facts left out of the report even further undermine the case.

Update: Added the weird ethics language.

OTHER POSTS ON THE DOJ IG REPORT

Overview and ancillary posts

DOJ IG Report on Carter Page and Related Issues: Mega Summary Post

The DOJ IG Report on Carter Page: Policy Considerations

Timeline of Key Events in DOJ IG Carter Page Report

Crossfire Hurricane Glossary (by bmaz)

Facts appearing in the Carter Page FISA applications

Nunes Memo v Schiff Memo: Neither Were Entirely Right

Rosemary Collyer Responds to the DOJ IG Report in Fairly Blasé Fashion

Report shortcomings

The Inspector General Report on Carter Page Fails to Meet the Standard It Applies to the FBI

“Fact Witness:” How Rod Rosenstein Got DOJ IG To Land a Plane on Bruce Ohr

Eleven Days after Releasing Their Report, DOJ IG Clarified What Crimes FBI Investigated

Factual revelations in the report

Deza: Oleg Deripaska’s Double Game

The Damning Revelations about George Papadopoulos in a DOJ IG Report Claiming Exculpatory Evidence

A Biased FBI Agent Was Running an Informant on an Oppo-Research Predicated Investigation–into Hillary–in 2016

The Carter Page IG Report Debunks a Key [Impeachment-Related] Conspiracy about Paul Manafort

The Flynn Predication

Sam Clovis Responded to a Question about Russia Interfering in the Election by Raising Voter ID

I’m still working on the serious parts of the reports from Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab’s FBI interrogations that Scott Shane liberated. But I wanted to share this detail, because it’s pretty funny.

I’m still working on the serious parts of the reports from Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab’s FBI interrogations that Scott Shane liberated. But I wanted to share this detail, because it’s pretty funny.

Even leaving out the context of the years during with Steele and Ohr had discussed matters of Russian oligarchs generally and Deripaska specifically, as the IG Report does, Deripaska’s feud with Paul Manafort — while likely crucial background to the dossier — cannot be described as content from

Even leaving out the context of the years during with Steele and Ohr had discussed matters of Russian oligarchs generally and Deripaska specifically, as the IG Report does, Deripaska’s feud with Paul Manafort — while likely crucial background to the dossier — cannot be described as content from