Over the last several weeks there has been considerable re-evaluation of the Iraq War, launched ten years ago by the Bush Administration. Eulogies and opinions from pundits of all types ranged from “I told you so,” to “It was a qualified success.”

We all know what the truth is without punditry: the war was a bolloxed-up mess before it began, and its outcome is tragic no matter the angle from which one views the results.

But with all the reassessment of the Bush years and its policies on Iraq, there’s been little revisiting of tangential foreign policies and their equally disturbing outcomes.

In particular, in spite of the ramped up threats of nuclear missile deployment, the damage of Bush policies on North Korea have not been discussed.

North Korea has been able to grow its nuclear program primarily because the Bush administration abruptly vacated the previous Clinton administration policy of engagement — in March 2001, a dozen years ago this month. Bush told a shocked South Korean president Kim Dae Jung about this unanticipated policy change in private during a summit. To reporters and the public at large, Bush says,

“Part of the problem in dealing with North Korea, there’s not very much transparency. We’re not certain as to whether or not they’re keeping all terms of all agreements.”

At the end of 2002, North Korea kicked out all IAEA inspectors — those which had been monitoring NK’s nuclear program under the Clinton administration’s previously negotiated 1994 Agreed Framework — thereby eliminating any transparency just as North Korea removed monitoring devices and seals from their nuclear program equipment.

In 2003, the Bush administration entered Six-Party talks with NK; the talks were on-again-off-again until 2009, when NK walked away entirely from discussions. Visiting U.S. scientists were allowed to see functioning uranium enrichment equipment in 2010.

North Korea being an extremely closed country, it is difficult if not impossible to insert operatives to monitor or thwart nuclear weapon development. It has taken considerable effort negotiating with other countries outside North Korea to deter raw materials or technology that could be used in proliferation.

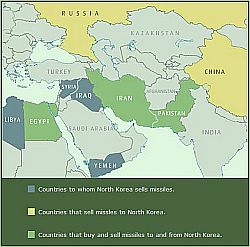

The American public cannot be certain that activities we’ve seen as part of “Arab Spring” weren’t encouraged by the Obama administration to act as a deterrent to proliferation. One need only look at the map graphic above to see how revolutionary activities in 2010-2011 may have impacted the flow of precursor content to/from North Korea from the sympathetic governments of Libya and Egypt — and now Syria.

Nor can the American public be certain about the parties with whom our government may negotiate, given the questions surrounding the last years and death of Kim Jong-il, Kim’s heir Kim Jong-un, and the shadowy military government supporting/operating the country. The intelligence community may have a handle on this, but they’re not sharing any information; the public is unable to insist on transparency and cannot readily hold NK’s true leadership to account via traditional media (bloggers attempt to do so on an informal basis).

Stuxnet (and quite possibly other cyber warfare applications) may also have been launched with a secondary target apart from Iran in mind. The nuclear development program in North Korea may have substantially similar components to that of Iran, including process control equipment. In theory such an attack might allow deterrence spread by Iran or other infected partners without attempting to insert operatives.

But the American public as well as most of the world can’t be certain that Stuxnet obstructed North Korean development because the country is so isolated. It’s possible that NK has been able to work around cyber warfare applications so that they have systems and enriched uranium to share with its existing nuclear partners. If they are trading materials and equipment with Iran, NK poses a threat to Israel and Saudi Arabia as well as the rest of the middle east.

Of all the anti-proliferation scenarios the world faces today, NK may be the worst case.

We can lay the blame solidly at the feet of the Bush administration’s policy wonks. As former U.S. Ambassador to South Korea (1989-1993) Donald Gregg said in 2003 about the administration’s position, the G. W. Bush administration “never had a policy. It’s had an attitude – hostility.”

Worse yet, Richard Perle, the former chair of the Defense Policy Board which advised the Bush administration’ Defense Department, said of the 1994 Framework Agreement,

“…The basic structure of the relationship implied in the Framework Agreement…is a relationship between a blackmailer and one who pays a blackmailer.”

Perle told the Bush administration that the U.S. doesn’t negotiate with extortionists.

And yet here we are, a dozen years later, forced to consider negotiations with a nuclear arsenal aimed at our heads, millions of South Koreans at immediate risk, while we vacillate on food aid to hungry North Koreans who suffer as leverage caught up in this debacle.

North Korea offers yet another fine neoconservative success borne of the Bush years – one showered with flowers and candy, reeking of freedom.

Recommended reading:

PBS Frontline: Kim’s Nuclear Gamble, (Mar 2003)

Arms Control Association’s Chronology of U.S.-North Korean Nuclear and Missile Diplomacy

Council on Foreign Relations’ The Six-Party Talks on North Korea’s Nuclear Program (Mar 2013)