Three Things: Colonialist Carrotage

[NB: check the byline, thanks. /~Rayne]

“What does colonialism have to do with carrots?” one might ask.

A lot — and an awful lot if you live in the U.S.

~ 3 ~

First, a bit of history which itself doesn’t have much to do with orange root vegetables.

130 years ago this past January there was a coup.

The last reigning monarch of the sovereign nation of Hawai’i was deposed by a bunch of white farmers – the guys who owned and operated sugar and pineapple farms on the islands, or the owners’ henchmen. They set up a provisional government composed of white guys who were the “Committee of Safety,” completely bypassing and ignoring the sentiments of the islands’ majority native Hawaiian population.

You’ll recall from your American History classes that a “Committee of Safety” was formed during the American Revolution as a shadow government. Groups later formed post-revolution with the same or similar names — a movement of vigilantism — but focused on protecting local white property owners’ interests.

Hawaiians had already been disenfranchised in 1887 when their king was forced to sign the “Bayonet Constitution” which removed much of his power while relegating Hawaiians and Asian residents to second-class non-voting status.

All because the Hawaiian islands were there and the sugar and pineapple producers wanted them.

That’s the rationalization. A bunch of brown people who had no army were stripped of their rights and their kingdom because white dudes wanted to farm there.

It didn’t help matters that the Hawaiian people had already been decimated by diseases the whites brought with them between Britain’s Captain Cook’s first foray into the islands in 1778 and the eventual annexation of Hawaii. As much as 85-90% of all Hawaiians died of communicable diseases like measles. There were too few Hawaiians remaining to fight off depredation by whites from the U.S. and Europe.

In 1993, then-president Bill Clinton signed a joint Apology Resolution Congress passed on the 100th anniversary of the coup, in which Congress said it “acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and further acknowledges that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi or through a plebiscite or referendum”.

None of that restores the sovereign nation of Hawai’i and makes it whole. It merely acknowledged the theft of an entire nation.

Am I a little chapped about this? Fuck yes, because my father’s family is Hawaiian and the land was stolen from them because the mainland U.S. wanted sugar and pineapples and the white dudes who stole it wanted a profit for little effort and didn’t give a damn about the nation of brown people who already existed on the islands. In contrast, Hawaiians like my family subsisted off the land and water.

They were merely collateral damage.

Happy fucking coup anniversary, white dudes from afar. You got what you wanted and more.

Hawaiians received nothing.

~ 2 ~

“But what does this have to do with carrots,” one might still be asking. “Is it the farmers?”

Yes, kind of — but it’s about the farmers’ attitudes.

Every single person who is not indigenous on this continent is on land which was already long occupied for thousands of years before whites arrived from Europe.

Much of this land is unceded territory, like the sovereign nation of Hawai’i. The rest may have been signed away in treaties, but get the fuck out about it being fair and equitable let alone fully informed and consensual, like the “Bayonet Constitution” King Kalākaua was forced to sign.

Here’s some 60 Dutch guilders, some alcohol, (sotto voce) some disease in exchange for the island of Manhattan. Fair trade, right? Such bullshit.

What’s even more bullshit is the argument some whites have used claiming indigenous people didn’t have a sense of ownership over the land. In a sense that’s true – many indigenous people felt or believed it was the other way around. They belonged to the land and to the forces of nature which made the land what it was, a holistic system.

This changes the concept of what a treaty entails, especially when both parties lack fluency in each other’s language and culture

(In Kalākaua’s case, there was no vagary; he was fluent in English and he knew if he didn’t sign the Bayonet Constitution the monarchy would be overthrown and the nation of Hawai’i would cease to exist.)

But who cared what those brown pagan savages thought? Even when they were converted to Christianity they were still brown and not perceived by whites as having legitimate rights to anything.

That included land and water.

This has pervaded white American history, that the people who pre-existed here were somehow not worth full consideration as equals. The attitude remains today when we talk about water and water rights.

The parallel thread to the marginalization of Native Americans and Hawaiians is the premise that white development should not ever be impeded (including development for its client states). If it needs something to expand and maintain itself, even if it exceeds its resources, it should simply be accommodated by whomever has the resources it needs.

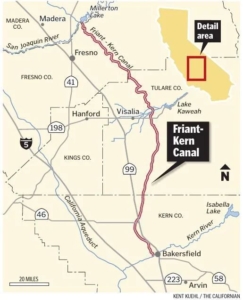

So it is with the west and water.

I’ve read tens of thousands of words this since January about water and the western U.S., and so very little of it is concerned with the rights of the people who were first here.

Where are their water rights in all of this demand for more water for agriculture?

What set me off on this was a comment responding to my last post about carrots in which it was suggested water for the west should come from the Midwest/eastern U.S.; it wasn’t the first time I’d heard such balderdash.

As if the Great Lakes region should simply give water because it has so much and the west needs it.

Oh, and the west will trade energy for it.

Like trading an island for 60 Dutch guilders. Or trading a nation for the bayonet removed from the throat.

No. Fuck no.

This is colonialism — its unending grasping nature to take what doesn’t belong to colonialists because they need it.

Like islands to grow sugar and pineapples, they want lakes to ensure their profits, I mean, carrots continue to grow.

Or their golf courses, or swimming pools, or their verdant fescue lawns in the middle of the desert.

Never mind the Great Lakes isn’t solely the property of the U.S., but a shared resource with its neighbor Canada.

Never mind there are First Nations Native Americans who also have water rights to the Great Lakes, who continue to rely on those lakes for their subsistence, and who may also subsist on the waters outside of Great Lakes but in other watersheds

No. Fuck no. The American west can knock off its colonialist attitude and grow up. Resources are finite, defining the limits of growth. Apply some of that vaunted American ingenuity and figure out how to make do with the resource budgets already available.

People are a lot easier to move than lakes full of water, by the way.

~ 1 ~

“Okay, carrots may be colonialist when they demand more water than available,” one might now be thinking.

Yes. But there’s more. Another issue which surface in comments on my last post was the lack of a comprehensive national water policy.

This is has been a problem for decades; it’s come up here in comments as far back as 2008, and the problem was ancient at that time.

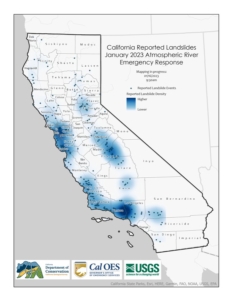

It’s not just a national water policy we need, though. We need a global policy in no small part because of the climate crisis. Look at California as this season’s storms begin to ease; the fifth largest economy in the world has been rattled with an excess of fresh water it can’t use effectively, which has and will continue to pose threats to CA residents. California is not the only place which will face such challenges. Super Typhoon Nanmadol last year dumped rain under high winds for days across all of Japan; while a typhoon is a discrete event, the size and length of Nanmadol are not unlike the effects of multiple atmospheric river events hitting California inside one week. The super typhoon hit Japan a month after a previous typhoon; imagine had they both been extended-length super typhoons.

Indeed, this is what has already happened in the Philippines before Nanmadol with Hinnamor.

This year has already seen the longest ever typhoon; Freddy lasted more than five weeks. Imagine a single super storm inflicting rain for that long in the East Asian region.

Depending on the level of development and preparedness, fresh water may be a problem during and after these much larger more frequent storms – not to mention drought and wildfire.

In 2010 the Defense Department’s Quadrennial Defense Review Report included a section addressing climate change:

Crafting a Strategic Approach to Climate and Energy

Climate change and energy are two key issues that will play a significant role in shaping the future security environment. Although they produce distinct types of challenges, climate change, energy security, and economic stability are inextricably linked. The actions that the Department takes now can prepare us to respond effectively to these challenges in the near term and in the future.

Climate change will affect DoD in two broad ways. First, climate change will shape the operating environment, roles, and missions that we undertake. The U.S. Global Change Research Program, composed of 13 federal agencies, reported in 2009 that climate-related changes are already being observed in every region of the world, including the United States and its coastal waters. Among these physical changes are increases in heavy downpours, rising temperature and sea level, rapidly retreating glaciers, thawing permafrost, lengthening growing seasons, lengthening ice-free seasons in the oceans and on lakes and rivers, earlier snowmelt, and alterations in river flows.

Assessments conducted by the intelligence community indicate that climate change could have significant geopolitical impacts around the world, contributing to poverty, environmental degradation, and the further weakening of fragile governments. Climate change will contribute to food and water scarcity, will increase the spread of disease, and may spur or exacerbate mass migration.

While climate change alone does not cause conflict, it may act as an accelerant of instability or conflict, placing a burden to respond on civilian institutions and militaries around the world. In addition, extreme weather events may lead to increased demands for defense support to civil authorities for humanitarian assistance or disaster response both within the United States and overseas. In some nations, the military is the only institution with the capacity to respond to a large-scale natural disaster. Proactive engagement with these countries can help build their capability to respond to such events. Working closely with relevant U.S. departments and agencies, DoD has undertaken environmental security cooperative initiatives with foreign militaries that represent a nonthreatening way of building trust, sharing best practices on installations management and operations, and developing response capacity.

Water — whether potable fresh, rising oceans, changed waterways, ice or lack thereof — figured prominently in this assessment of growing climate threats.

The inaugural Quadrennial Diplomacy Report published by the State Department in 2010 likewise considered climate change an issue demanding consideration as State assessed diplomatic efforts needed to assure the U.S. remained secure.

The climate crisis isn’t confined to the U.S. alone, though; it’s a global challenge and in need of global response. We need not only a national water policy but a global water policy, and with it policies related to agriculture dependent upon water’s availability.

The price for failing to implement a global approach has long-term repercussions. Examples:

• Ongoing conflict in Syria may have been kicked off before Arab Spring by long-term drought in the region;

• Violence and economic instability in Central America caused in part by drought and storms creates large numbers of asylum seekers and climate refugees heading north;

• Sustained drought in Afghanistan damaging crops increases the chances poor farmers will be recruited by the Taliban.

Developing approaches to ensure adequate clean drinking water and irrigation of local crops at subsistence level could help reduce conflicts, but it will require more than spot agreements on a case-by-case basis to scale up the kind of systems needed as the climate crisis deepens, affecting more of the globe at the same time.

~ 0 ~

“But wait, what about the carrots and colonialism and conflict?” one might ask.

The largest producers of carrots are China (Asia), the United States (western hemisphere), Russia, Uzbekistan — and Ukraine.

The third largest producer of carrots attacked the fifth largest producer which happened to be a former satellite state.

That besieged state is the largest producer of carrots in Europe.

The colonialism is bad enough. Imagine if the colonial power damaged the former colony’s water supply, too.