Even the First Roger Stone Sentencing Memo Was Politicized

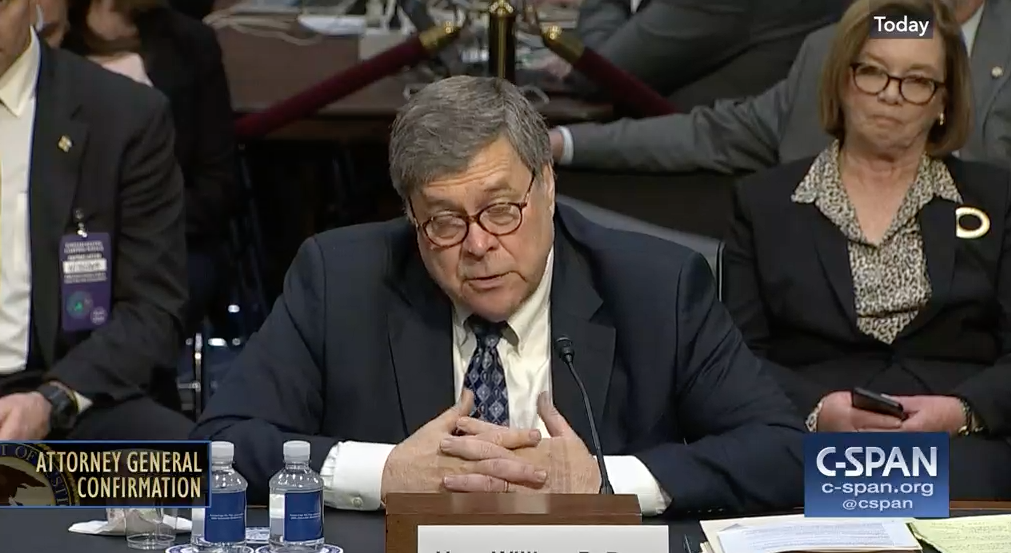

Mueller prosecutor Aaron Zelinsky’s testimony for a House Judiciary Committee hearing on how Trump and Barr are politicizing DOJ has been released. As a number of outlets are reporting, he will testify about how, when Bill Barr flunky Timothy Shea was bending to pressure to “cut Stone a break,” Shea did so because he was “afraid of the President.”

I’m more interested in a few details about the actual drafting of the memos, some of which I’ll return to. The original draft of the sentencing memo was drafted by February 5; it was not only approved, but deemed “strong.”

The prosecution team – which consisted of three career prosecutors in addition to myself – prepared a draft sentencing memorandum reflecting this calculation and recommending a sentence at the low end of the Guidelines range. We sent our draft for review to the leadership of the U.S. Attorney’s Office. We received word back from one of the supervisors on February 5, 2020, that the sentencing memo was strong, and that Stone “deserve[d] every day” of our recommendation.

On February 7, the hierarchy started intervening. In addition to asking to drop the enhancements (which is what the final memo did), DOJ big-wigs also asked prosecutors to take out language about Stone’s conduct.

However, just two days later, I learned that our team was being pressured by the leadership of the U.S. Attorney’s Office not to seek all of the Guidelines enhancements that applied to Stone – that is, to provide an inaccurate Guidelines calculation that would result in a lower sentencing range. In particular, there was pressure not to seek enhancements for Stone’s conduct prior to trial, the content of the threats he made to Credico, and the impact of his obstructive acts on the HPSCI investigation. Failure to seek these enhancements would have been contrary to the record in the case and to the Department’s policy that the government must ensure that the relevant facts and sentencing factors are brought to the court’s attention fully and accurately.

When we pushed back against incorrectly calculating the Guidelines, office leadership asked us instead to agree to recommend an open-ended downward variance from the Guidelines –to say that whatever the Guidelines recommended, Stone should get less. We repeatedly argued that failing to seek all relevant enhancements, or recommending a below-Guidelines sentence without support for doing so, would be inappropriate under DOJ policy and the practice of the D.C. U.S. Attorney’s Office, and that given the nature of Stone’s criminal activity and his wrongful conduct throughout the case, it was not warranted.

In response, we were told by a supervisor that the U.S. Attorney had political reasons for his instructions, which our supervisor agreed was unethical and wrong. However, we were instructed that we should go along with the U.S. Attorney’s instructions, because this case was “not the hill worth dying on” and that we could “lose our jobs” if we did not toe the line.

We responded that cutting a defendant a break because of his relationship to the President undermined the fundamental principles of the Department of Justice, and that we felt that was an important principle to defend.

Meanwhile, senior U.S. Attorney’s Office leadership also communicated an instruction from the acting U.S. Attorney that we remove portions of the sentencing memorandum that described Stone’s conduct. Again, this instruction was inconsistent with the usual practice in the U.S. Attorney’s Office, and with the Department’s policy that attorneys for the government must ensure that relevant facts are brought the attention of the sentencing court fully and accurately.

Ultimately, we refused to modify our memorandum to ask for a substantially lower sentence. Again, I was told that the U.S. Attorney’s instructions had nothing to do with Mr. Stone, the facts of the case, the law, or Department policy. Instead, I was explicitly told that the motivation for changing the sentencing memo was political, and because the U.S. Attorney was “afraid of the President.”

Ultimately, Tim Shea approved the prosecutors’ inclusion of the enhancements, but took out the language about Stone’s conduct.

On Monday, February 10, 2020, after these conversations, I informed leadership at the U.S. Attorney’s Office in D.C. that I would withdraw from the case rather than sign a memo that was the result of wrongful political pressure. I was told that the acting U.S. Attorney was considering our recommendation and that no final decision had been made.

At 7:30PM Monday night, we were informed that we had received approval to file our sentencing memo with a recommendation for a Guidelines sentence, but with the language describing Stone’s conduct removed. We filed the memorandum immediately that evening.

That means even the first sentencing memo — the one that made a strong case for prison time — had been softened by Barr’s flunkies, in some way not laid out in Zelinsky’s opening statement.

Here’s the first sentencing memo. One thing lacking from that memo — but in Zelinsky’s opening statement — pertains to Stone’s discussions directly with Trump.

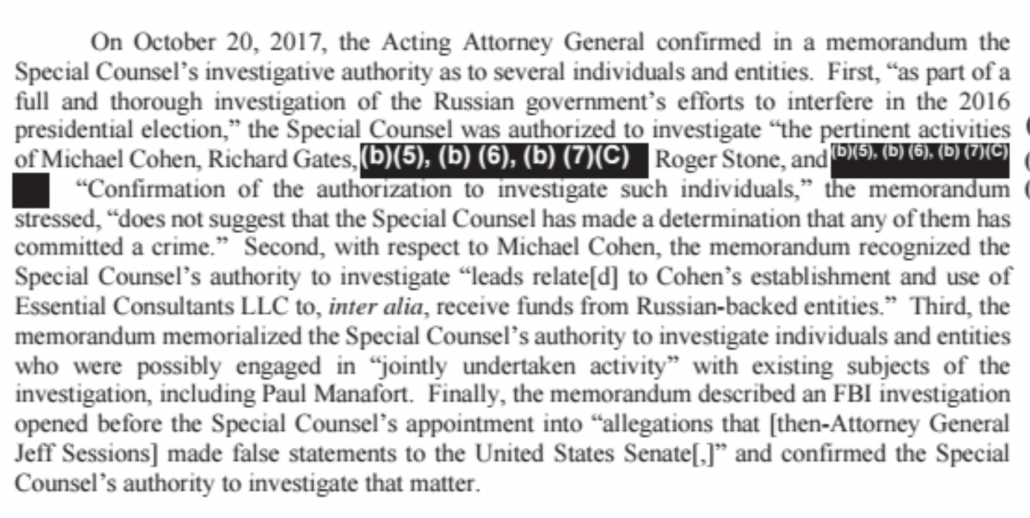

And that summer, Stone wasn’t just talking to the CEO, Chairman, and Deputy Chairman of the campaign. He was talking directly to then-candidate Trump himself.

On June 14, 2016, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) announced that it had been hacked earlier that spring by the Russian Government. That evening, Stone called Trump, and they spoke on Trump’s personal line. We don’t know what they said.

On August 2, [sic — this should be July 31] Stone again called then-candidate Trump, and the two spoke for approximately ten minutes. Again, we don’t know what was said, but less than an hour after speaking with Trump, Stone emailed an associate of his, Jerome Corsi, to have someone else who was living in London “see Assange.”

Less than two days later, on August 2, 2016, Corsi emailed Stone. Corsi told Stone that, “Word is friend in embassy [Assange] plans 2 more dumps. One “in October” and that “impact planned to be very damaging,” “time to let more than Podesta to be exposed as in bed w enemy if they are not ready to drop HRC. That appears to be the game hackers are now about.”

Around this time, Deputy Campaign Chairman Gates continued to have conversations with Stone about more information that would be coming out from WikiLeaks. Gates was also present for a phone call between Stone and Trump. While Gates couldn’t hear the content of the call, he could hear Stone’s voice on the phone and see his name on the caller ID. Thirty seconds after hanging up the phone with Stone, then-candidate Trump told Gates that there would be more information coming. Trump’s personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, also stated that he was present for a phone call between Trump and Stone, where Stone told Trump that he had just gotten off the phone with Julian Assange and in a couple of days WikiLeaks would release information, and Trump responded, “oh good, alright.” Paul Manafort also stated that he spoke with Trump about Stone’s predictions and his claimed access to WikiLeaks, and that Trump instructed Manafort to stay in touch with Stone.

Surely there’s someone sharp enough on HJC who can note this discrepancy and ask Zelinsky whether there was similar language in the sentencing memo that Tim Shea took out because he’s “afraid of the President.”

Zelinsky knows little about the drafting of the second memo — he describes that he heard about it in the press and the rest of his understanding appears to come from what he was told in the office.

What he was told was that DOJ actually considered attacking its own prosecutors in the memo.

We repeatedly asked to see that new memorandum prior to its filing. Our request was denied. We were not informed about the content or substance of the proposed filing, or even who was writing it. We were told that one potential draft of the filing attacked us personally.

This is akin to the Mike Flynn motion to dismiss, which insinuated that prosecutors had engaged in misconduct. The Attorney General and his flunkies are attacking career officials at DOJ to perform for the President like trained seals.

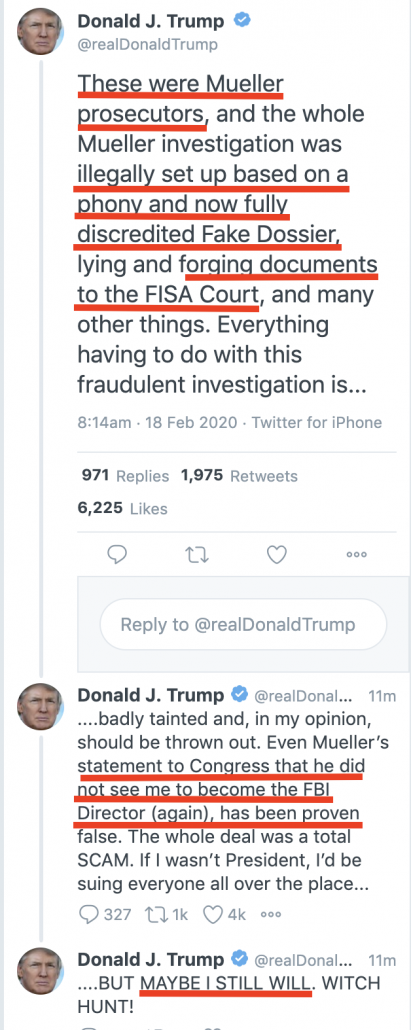

In the passage where Zelinsky offers his opinion of that second memo he notes that it matched Trump’s tweet of the interim day.

The new filing stated that the first memo did not “accurately reflect” the views of the Department of Justice. This new memo muddled the analysis of the appropriate Guidelines range in ways that were contrary to the record and in conflict with Department policy. The memo said that the Guidelines were “perhaps technically applicable,” but attempted to minimize Stone’s conduct in threatening Credico and cast doubt on the applicability of the resulting enhancement, claiming that the enhancement “typically” did not apply to first time offenders who were not “part of a violent criminal organization.” The memo also stated that Stone’s lies to the Judge about the meaning of the image with the crosshairs and how it came to be posted on Instagram “overlaps to a degree with the offense conduct in this case,” and therefore should not be the basis for an enhancement.

The new memo did not engage with testimony in the record about Credico’s concerns. Nor did the new memo engage with cases cited in the old memo where the obstruction enhancement was applied to non-violent first-time offenders. And the memo provided no analysis for why Stone’s lies to Congress regarding WikiLeaks overlapped at all with his lies two years later to the judge about his posting images of her with a crosshairs. The new memo also stated that the court should give Stone a lower sentence because of his “health,” though it provided no support for that contention, and the Guidelines explicitly discourage downward adjustments on that basis.

Ultimately, the memo argued, Stone deserved at least some time in jail– though it did not give an indication of what was reasonable. All the memo said was that a Guidelines sentence was “excessive and unwarranted,” matching the President’s tweet from that morning calling our recommendation “horrible and very unfair.” [my emphasis]

Zelinsky’s read of that second memo also complains that it left out the record on Randy Credico’s response to Stone’s threats. In his opening statement, he provides this detail, which I don’t recall from the trial (Amy Berman Jackson was able to rely on Credico’s grand jury transcript in her sentencing, because Stone had submitted that with one of his filings).

Then, fearful of what Stone’s associates might do to him, Credico moved out of his house and wore a disguise when going outside.

Credico explains that he grew a thick mustache and wore a cap and sunglasses. Dressing up as John Bolton is indeed a fearful disguise.

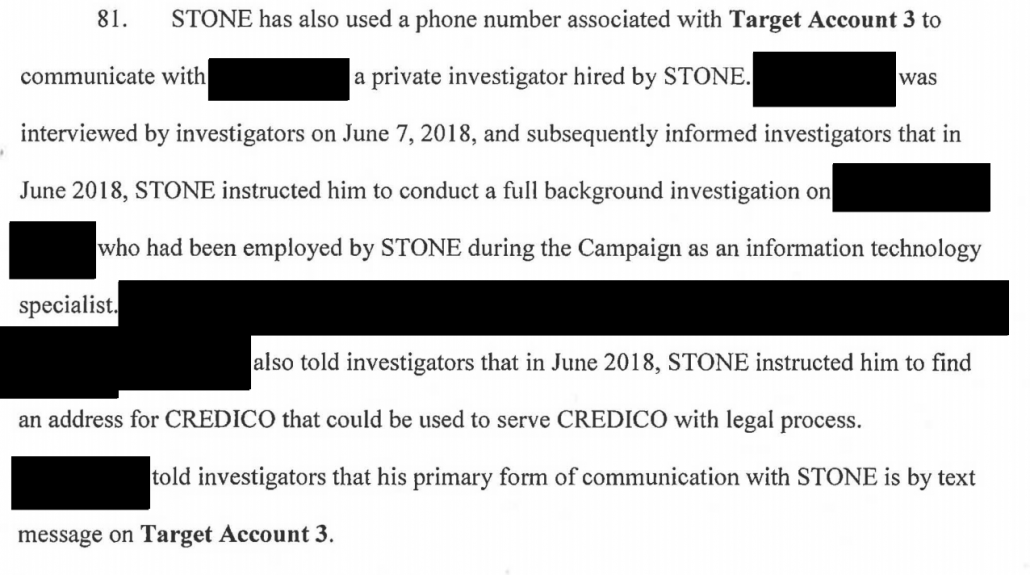

The detail that Credico moved out of his house, taken in conjunction with the detail from the Stone warrants that Stone hired a private investigator to find an address to “serve” Credico with a subpoena he never served him, is especially chilling.

Stone hired a PI to hunt Credico down after Credico took measures to hide from him and (Credico has always emphasized) Stone’s violent racist friends.

In addition to making it clear that Shea politicized even the first memo in some way, Zelinsky hints at ways that Stone’s witness tampering was more aggressive than widely understood.

Let’s hope those details come out in tomorrow’s hearing.