On emptywheel’s Continued Obsession with Oligarch Real Estate Seizures

DOJ rolled out another sanctions-related action targeting those who allegedly managed sanctioned Russian oligarchs’ real estate the other day. It charged Vladimir Voronchenko with making payments to maintain four properties, amounting to $75 million in value, owned by Viktor Vekselsberg. The properties include a big home in Southhampton, a condo on Park Avenue, a Penthouse on Miami’s Fisher Island, and a smaller apartment just around the corner from the Penthouse.

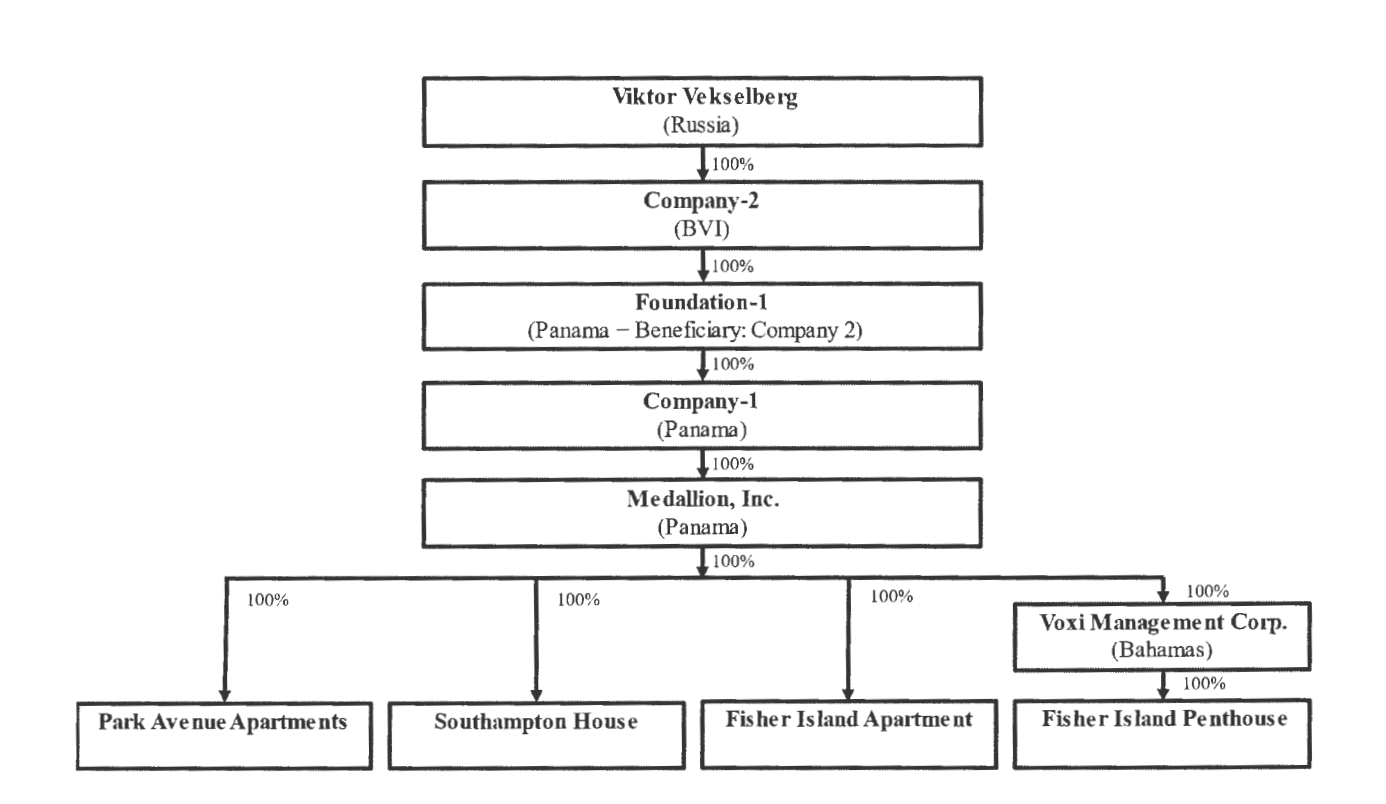

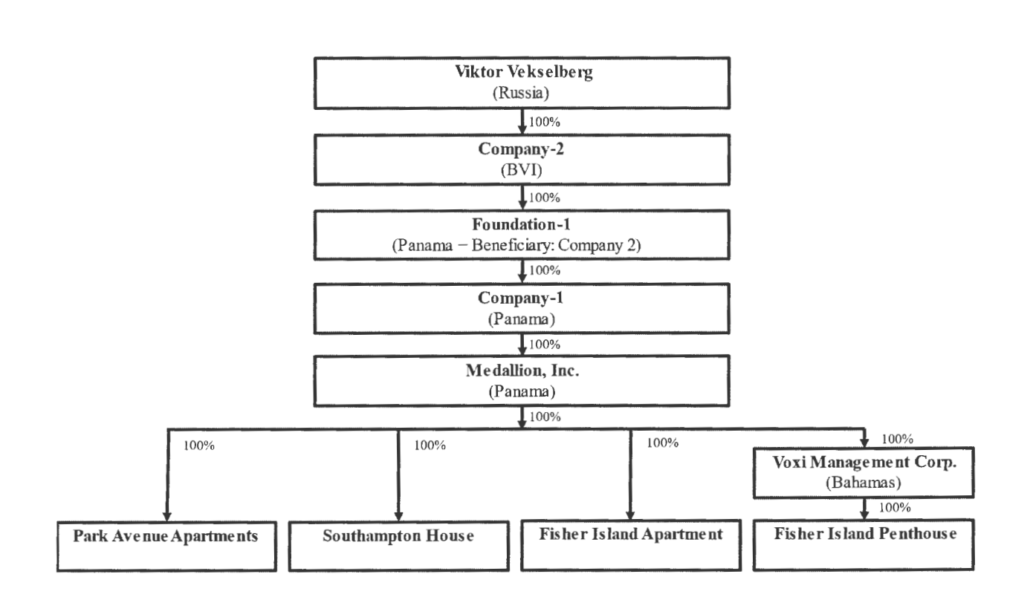

The story told in the indictment is simple. Between 2008 and 2017, Vekselberg purchased the properties via some shell companies. Voronchenko managed the properties through an IOLTA account funded by Vekselberg. Then, after Vekselberg was first sanctioned in April 2018, Voronchenko started making the payments into the IOLTA fund himself. Both those payments, and attempts to sell the Southampton House in 2020 and the Park Avenue condo in 2021, required an OFAC license, the indictment alleges.

Two days after DOJ subpoenaed Voronchenko on May 13, 2022, he fled, first to Dubai and, from there, to Russia.

I’m interested in how and whom the indictment charges, as compared to two earlier actions against Russian oligarchs. The indictment against Oleg Deripaska, his girlfriend, and two women who managed his US-based properties charges only conspiracy to violate IEEPA (plus some obstruction-related charges). The EDNY indictment against Andrii Derkach charges conspiracy to violate IEEPA and conspiracy to commit money laundering, as well as bank fraud and some other financial crimes. Both of those were charged last September (though Derkach’s indictment wasn’t unsealed until they took action to secure the LA properties they’re attempting to seize).

Like those earlier indictments, this one also charges a conspiracy to violate IEEPA. Like the Derkach indictment, it also charges conspiracy to commit money laundering. But it also charges Voronchenko with those crimes individually, violation of IEEPA and money laundering, along with contempt for fleeing after receiving the subpoena.

I’m interested in the timing — the charges against Deripaska (which was actually a superseding indictment) and Derkach were September. For some reason, DOJ waited to charge this one (perhaps they were waiting to see if Voronchenko would return to the scene of his alleged crime).

More curiously, they charge Vorochenko alone.

Admittedly, that’s how DOJ initially charged Derkach, too. They superseded the indictment in January to include his spouse, Oksana Terkhova.

Which is why I’m interested in some other people described in his indictment.

Obviously, there’s Vekselberg himself, who unlike Deripaska and Derkach, was not charged for dodging sanctions to sustain his properties.

There are three Voronchenko family members, each treated a bit differently. Family member-1 applied, with Voronchenko, for membership in the club at Fisher Island.

Family member-2 lived in Russia, where he or she was helping to transfer funds for the upkeep of the properties.

A third family member, Family member-3, was involved in efforts to sell the Park Avenue property starting in December 2021.

A different Vorochenko relative in Russia, described as Individual-2, controlled a bank account in Russia from which the IOLTA was funded after Vekselberg was sanctioned. As described, Individual-2 seems to have more legal liability than Vorochenko’s other family members (because he or she would have been involved in any alleged money laundering).

The fact that Individual-2, who would seem to be implicated in money laundering, is described differently than the other family members is of interest because there is an Individual-1. As described, that person is only in the indictment to substantiate that Voronchenko was aware of the sanctions against Vekselberg.

[O]n or about May 9, 2018, approximately one month after Vekselberg’s designation, VORONCHENKO sent a WhatsApp message to an associate (“Individual-1”) with a link to the website of a law firm in Washington, D.C. that specialized only in OFAC sanctions. On or about December 8, 2018, VORONCHENKO sent a WhatsApp message to Individual-1 containing a link to an article that discussed Vekselberg’s designation as an SDN.

It’s not criminal at all for Individual-1 to receive texts about sanctions against Vekselberg. This person may only be in the indictment, described as such, for that substantiation of Voronchenko’s knowledge of the sanctions.

But I’m interested in that second WhatsApp text.

The day before Voronchenko sent the text, Bloomberg published a long story about Vekselberg. It’s not exclusively about sanctions.

Rather, it’s the story about how Vekselberg’s effort to cultivate Michael Cohen — his payment of vast sums starting in 2017 to, basically, do nothing — ultimately led to his questioning by Mueller and then, a month later, his sanctioning.

Not long after Michael Cohen stopped pursuing a Trump-branded property project in Moscow, another Russian connection to the future U.S. president’s entourage started to form.

Like the real estate plan, it didn’t end well—particularly for Russian tycoon Viktor Vekselberg. His effort to engage in statecraft at the highest level unraveled spectacularly, costing him billions, cleaving his family and severing the extensive ties to the U.S. elite that turned him into what one Moscow newspaper called the “most American” of Vladimir Putin’s plutocrats.

This saga, much of it previously unreported, began with a chance encounter between Cohen, Trump’s now-disgraced former lawyer, and Vekselberg’s American cousin, Andrew Intrater, in the fall of 2016. Soon, Trump would be in the White House and Vekselberg would be privately boasting of having the pull needed to help achieve the sanctions relief the Kremlin was craving, people familiar with the matter said. Instead, he became the richest victim of the most dangerous standoff between the U.S. and Russia since the Cold War.

[snip]

Through much of 2017, as the nascent Trump administration navigated controversies of its own making, Vekselberg was giving Russian officials and fellow businessmen vague yet certain assurances about his influence in the White House, according to six people who interacted with him at the time. He’d attended Trump’s swearing-in ceremony in Washington as a guest of Intrater, who’d donated $250,000 to the inaugural committee, and come back with a newfound sense of clout, they said.

As the story describes, Mueller was quite interested in whether Intrater was serving as a front for donations from Vekselberg.

In March, during one of his last trips to the U.S., he was stopped and questioned by Mueller’s team at an airport in the New York area. They asked about his ties to Cohen, who faces sentencing on Dec. 12 for confessed crimes that include violating campaign-finance rules. Investigators also asked why he attended Trump’s inauguration and if Intrater’s $250,000 gift was actually his money.

[snip]

Mueller’s interest in Intrater, who’s been questioned twice, is telling. One area his team is known to be exploring is whether wealthy Russians funneled cash into Trump’s campaign or inauguration through U.S. citizens to bypass rules barring foreign donations. Federal Elections Commission data show Intrater had never made a political donation of more than $2,600 prior to Trump.

I was reviewing all this just the other day (I link the affidavit showing how the payments from Renova to Cohen led to the investigation against him in my last post on Jeff Gerth, which I’ll post later today or tomorrow). Remarkably, Mueller never did anything with the Vekselberg’s outreach to Cohen. Neither Vekselberg nor Andrew Intrater show up in the Mueller Report.

Of course, the question of whether Intrater is laundering donations for Vekselberg has become urgently important again. As the WaPo and NYT have both covered, Intrater claims he was duped by Santos to invest in the Ponzi scheme for which he was working.

A month after the Securities and Exchange Commission filed a lawsuit in 2021 accusing a Florida-based company of operating a Ponzi scheme, one of the firm’s account managers assured an anxious client that his money was safe.

The client, a wealthy investor named Andrew Intrater, had been lured by annual returns of 16 percent and had invested $625,000 in a fund offered by the company, Harbor City Capital — in part because he trusted and admired the account manager, an aspiring politician named George Santos.

Admiration aside, Mr. Intrater wanted to know about his investment and a promised letter of credit that secured it. Mr. Santos said that it was already on the way.

“All issued and sent over,” Mr. Santos assured him in a text message sent in May 2021.

The letter of credit did not exist, the S.E.C. would later tell a court. The $100 million that Mr. Santos told Mr. Intrater that he had personally raised for Harbor City did not exist either, the commission said. Nor, seemingly, did the close to $4 million that Mr. Santos claimed he and his family had invested in Harbor City.

Mr. Santos’s representations form the basis of a sworn declaration that Mr. Intrater gave the S.E.C. in May 2022, as part of its Harbor City investigation. Mr. Intrater’s interactions with the S.E.C. are the first indication the commission might be interested in Mr. Santos.

Mr. Intrater told the S.E.C. that the representations influenced his decision to invest in Mr. Santos’s business and political endeavors — an allegation that could leave Mr. Santos vulnerable to criminal charges.

Intrater’s claim to have been duped makes it all the more curious that he donated heavily to Santos, including after he was purportedly duped.

Santos received contributions in multiple installments from Intrater between 2020 and 2022. The financier made two donations to Santos’ joint fundraising committees in 2022; $12,200 to the Devolder Santos Nassau Victory Committee and $10,800 to the DeVolder Santos Victory Committee. These, along with additional donations from Intrater, were bucketed into Santos’ leadership PAC, Gads PAC, which received a total of $12,100 between 2021 and 2022, the Nassau County Republican Committee received $10,000 in 2022, and to Santos’ campaign directly, who received a total of $12,200 in four installments between 2020 and 2022.

So I’m sure DOJ has an acute, renewed interest in the propriety of Intrater’s political donations.

Vorochenko got indicted, in a conspiracy, all by himself.

But he was speaking to someone about matters covered by the conspiracy that quickly lead into far more suspicious matters.

Update: I’m down so many different rabbit holes I forgot to link the Vekselberg action charged last month against the guys maintaining Vekselberg’s yacht in Mallorca. It describes the front companies Vekselberg used for the yacht, which may be the same shown above in the graphic.

As I noted there, one interesting aspect of the charge was venue: DC instead of one of the places where foreigners would be flown into (like EDNY, for JFK, or EDVA, for any of the VA airports), which is how venue is often assigned. The venue is all the weirder now that we see this indictment charged in SDNY. The SDNY press release thanks the FBI, but doesn’t say whether this case was (like the yacht charges) investigated by MN FBI agents.

Update, February 23: SDNY is now moving to seize the properties.