Eight days ago, the country’s four major newspapers reported a claim that the NSA collected 33% or less of US phone records (under the Section 215 program, they should have specified, but did not) because it couldn’t collect most cell phone metadata:

- “[I]t doesn’t cover records for most cellphones,” (WSJ)

- “[T]he agency has struggled to prepare its database to handle vast amounts of cellphone data,” (WaPo)

- “[I]t has struggled to take in cellphone data,” (NYT)

- “[T]he NSA is gathering toll records from most domestic land line calls, but is incapable of collecting those from most cellphone or Internet calls.” (LAT)

Since that time, I have pointed to a number of pieces of evidence that suggest these claims are only narrowly true:

- A WSJ article from June made it clear the cell gap, such as it existed, existed primarily for Verizon and T-Mobile, but their calls were collected via other means (the WaPo and NYT both noted this in their stories without considering how WSJ’s earlier claim it was still near-comprehensive contradicted the 33% claim)

- The NSA’s claimed Section 215 dragnet successes — Basaaly Moalin, Najibullah Zazi, Tsarnaev brothers — all involved cell users

- Identifying Moalin via the dragnet likely would have been impossible if NSA didn’t have access to T-Mobile cell data

- The phone dragnet orders specifically included cell phone identifiers starting in 2008

- Also since 2008, phone dragnet orders seem to explicitly allow contact-chaining on cell identifiers, and several of the tools they use with phone dragnet data specifically pertain to cell phones

Now you don’t have to take my word for it. Here’s what Keith Alexander had to say about the claim Friday:

Responding to a question about recent reports that the NSA collects data on only 20% to 30% of calls involving U.S. numbers, Alexander acknowledged that the agency doesn’t have full coverage of those calls. He wouldn’t say what fraction of the calls NSA gets information on, but specifically denied that the agency is completely missing data on calls made with cell phones.

“That part is not true,” he said. “We don’t get it all. We don’t get 100% of the data. It’s not where we want it to be, but it has been sufficient to go after the key targets that we’re going after.” [my emphasis]

Admittedly, Alexander is not always entirely honest, so it’s possible he’s just trying to dissuade terrorists from using cellphones while the NSA isn’t tracking them. But he points to the same evidence I did — that NSA has gotten key targets who use cell phones.

There’s something else Alexander said that might better explain the slew of claims that it can’t collect cell phone data.

The NSA director, who is expected to retire within weeks, indicated that some of the gaps in coverage are due to the fact that the NSA “paused any changes to the program” during the recent controversy and discussions about restructuring the effort.

The NSA has paused changes to the program.

This echoes WaPo and WSJ reports that crises (they cited both the 2009 and current crisis) delayed some work on integrating cell data, but suggests that NSA was already making changes when the Snowden leaks started.

There is evidence the pause — or at least part of it — extends back to before the Snowden leak. As I reported last week, even though the NSA has had authority to conduct a new auto-alert on the phone dragnet since November 2012, they’ve never been able to use it because of technical reasons.

The Court understands that to date NSA has not implemented, and for the duration of this authorization will not as a technical matter be in a position to implement, the automated query process authorized by prior orders of this Court for analytical purposes.

This description actually came from DOJ, not the FISC, and I suspect the issue is rather that NSA has not solved some technical issues that would allow it to perform the auto-alert within the legal limits laid out by the FISC (we don’t know what those limits are because the Administration is withholding the Primary Order Supplement that would describe it, and redacting the description of the search itself in all subsequent orders).

That said, there are plenty of reasons to believe there are new reasons why NSA is having problems collecting cell phone data because it includes cell location, which is far different than claiming (abundant evidence to the contrary) they haven’t been collecting cell data all this time. In addition to whatever reason NSA decided to stop its cell location pilot in 2011 and the evolving understanding of how the US v. Jones decision might affect NSA’s phone dragnet program, 3 more things have happened since the beginning of the Snowden leaks:

- On July 19, Claire Eagan specifically excluded the collection of cell site location information under the Section 215 authority

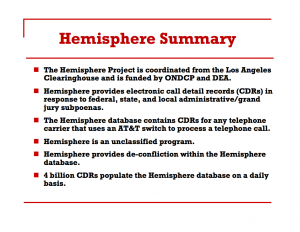

- On September 1, NYT exposed AT&T’s Hemisphere program; not only might this give AT&T reason to stop collating such data, but if Hemisphere is the underlying source for AT&T’s Section 215 response, then it includes cell location data that is now prohibited

- On September 2, Verizon announced plans to split from Vodaphone, which might affect how much of its data, including phone metadata, is available to NSA via GCHQ under the Tempora program; that change legally takes effect February 21

Remember, too, there’s a February 2013 FISC Section 215 opinion the Administration is also still withholding, which also might explain some of the “technical-meaning-legal” problems they’re having.

Underlying this all (and assuredly underlying the problems with collecting VOIP calls, which are far easier to understand and has been mentioned in some of this reporting, including the LAT story) is a restriction arising from using an ill-suited law like Section 215 to collect a phone dragnet: telecoms can only be obligated to turn over records they actually “already generate,” as described by NSA’s SID Director Theresa Shea.

[P]ursuant to the FISC’s orders, telecommunications service providers turn over to the NSA business records that the companies already generate and maintain for their own pre-existing business purposes (such as billing and fraud prevention).

To the extent telecoms use SS7 data, which includes cell location, to fulfill their Section 215 obligation (after all, what telecoms need billing records on a daily basis?), it probably does introduce problems.

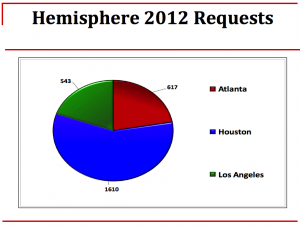

Which, I suspect, will mean that Alexander and the rest of the dragnet defenders will recommend that a third party collate and store all this data, the worst of all solutions. They need to have a comprehensive source (like Hemisphere apparently plays for the DEA), one that will shield the government from necessarily having collected cell location data that is increasingly legally suspect to obtain. And they’ll celebrate it as a great sop to the civil libertarians, too, when in fact, they’ve probably reached the point where it is clear Section 215 can’t legally authorize what it is they want it to do.

The issue, more and more evidence suggests, is that they can’t collect the dragnet data without a law designed to construct the dragnet. Which is another way of saying the dragnet, as intended to function, is illegal.