As I laid out here, the latest NYT obstruct-a-palooza on Don McGahn “cooperating” with Robert Mueller spins what is probably a lawyer covering his own legal jeopardy with a claim of full cooperation.

But why did he (and his lawyer, William Burck) cooperate in it? Why spin a fanciful tale of being disloyal to your boss, even if it’s just to blame him for it before he blames you?

The most obvious answer is he’s trying to convince Mueller he’s not responsible for the legal shenanigans of (as the NYT continues to spin it) the obstruction of the investigation, or of the legal shenanigans of Trump generally.

There may well be an aspect of that, though I wouldn’t want to be (and hope I’m not) in a position where my legal jeopardy relied on how successfully I could spin Maggie and Mike, even if I were as expert at doing so as Don McGahn is.

A better answer may lie in this observation from my last post:

By far the most telling passage in this 2,225+ word story laying out Don McGahn’s “cooperation” with the Mueller inquiry is this passage:

Though he was a senior campaign aide, it is not clear whether Mr. Mueller’s investigators have questioned Mr. McGahn about whether Trump associates coordinated with Russia’s effort to influence the election.

Over two thousand words and over a dozen sources, and Maggie and Mike never get around to explaining whether Don McGahn has any exposure in or provided testimony for the investigation in chief, the conspiracy with Russia to win the election.

Consider: the story Maggie and Mike (and Don McGahn’s lawyer) spin is that Don McGahn let Trump bully him around on some issues in early 2017, which led to some things that might look like obstruction of justice. An unfortunate occurrence, surely. But McGahn might be forgiven for fucking things up in early January 2017. After all, he was new to the whole White House Counseling thing; he had never worked in a White House before. Beginner’s mistake(s), you might call the long list of things he fucked up at the beginning of his tenure, which Maggie and Mike nod to but don’t describe in full resplendent glory.

His relationship with the president had soured as Mr. Trump blamed him for a number of fraught moments in his first months in office, including the chaotic, failed early attempts at a ban on travelers from some majority-Muslim countries and, in particular, the existence of Mr. Mueller’s investigation.

Don McGahn’s skills, it turns out, lie elsewhere.

While he has bolloxed most of the things White House Counsels are supposed to do (like keeping the White House out of legal and ethical trouble), he has had unsurpassed success at stacking the courts. I doubt there’s an ideological Republican in the country who isn’t thrilled with McGahn’s success at stacking the courts.

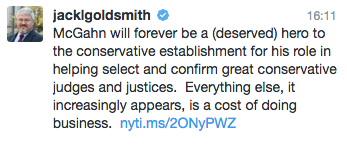

Update: Case in point.

Indeed (this becomes important in just a bit), McGahn’s success at stacking the courts is one of the biggest reasons why Republicans in Congress put up with the rest of Trump’s shit. Being President, for many Republicans, isn’t about governing; it’s about stacking the courts.

It turns out, though, that McGahn had another job before he became an expert court-stacker. For decades, Don McGahn has been one of the Republican party’s key campaign finance lawyers.

That’s how he grew to be close to Trump when, as Maggie and Mike describe,

McGahn joined the Trump team as an early hire said to like the candidate’s outsider position.

Don McGahn had come to prominence in the party at the NRCC and was rewarded for it with a seat on the FEC, where he made campaign finance more slushy.

But probably not slushy enough.

Here’s where Maggie and Mike’s failure to get an answer for whether longtime Republican campaign finance expert Don McGahn has been questioned about his role in the conspiracy with Russians to win the election (not to mention their failure to pin down when his third interview with Mueller’s team took place, after he happily revealed when the first two did) becomes important.

Don McGahn might be forgiven for bolloxing up the White House Counsel job. He was new at that (and he was busy, anyway, stacking the courts).

But at least three of the areas where Mueller’s team might find a conspiracy with Russia (or other foreigners) to win the election involve campaign finance issues — Don McGahn’s expertise. Those are:

- Whether knowingly employing British Cambridge Analytica employees without getting them proper visas constitutes illegal foreign influence?

- Whether accepting a Trump Tower meeting with Russians offering dirt on Hillary Clinton constitutes accepting a thing of value?

- Whether the campaign was sufficiently firewalled from the dodgy shit Roger Stone was doing (which has been a focus of the last six months of Mueller’s time)?

My wildarse guess is that campaign finance expert Don McGahn might find a way to finesse hiring foreign Cambridge Analytica employees. My wildarse guess is that campaign finance expert Don McGahn could claim ignorance about the illegal details of the Trump Tower and other foreign influence peddling meetings.

My wildarse guess is that campaign finance expert Don McGahn did not sufficiently firewall Stone off from the campaign. Especially given that he was involved in both incarnations of Stop the Steal — the effort to stamp down a convention rebellion, and the effort (which worked in parallel to a Russian one) to use claims of a “rigged” election to suppress Democratic voters. Especially given that he was loved in the Republican party for leaning towards slush over legal compliance.

Given how central campaign finance violations are in any question of a conspiracy with Russia, it is malpractice for Maggie and Mike to publish a story without determining whether — after being grilled by Mueller’s team for two days last fall about whether he fucked up White House Counseling — McGahn has more recently been grilled extensively about whether he fucked up campaign finance, the thing he got hired for in the first place. The thing he’s supposed to be an expert in.

But Maggie and Mike believe Trump is only being investigated for obstruction, so seeding a big puff piece with them is a sure bet you won’t get asked about your obviously central role (or not) in any conspiracy involving campaign finance.

That’s just part of a potential explanation for why Don McGahn (and his lawyer) would seed a big puff piece with Maggie and Mike, making it look like McGahn had cooperated a lot on something he was never an expert in — White House Counseling — but remaining utterly silent on whether he cooperated on something he is undoubtedly an expert in (even if he tends to prefer slush to law). Better to get in trouble for cooperating on the stuff Trump and his lawyers have been successfully distracting with for the last six months rather than cooperating with prosecutors on a case about conspiring with Russian spies to win an election, the stuff that will elicit cries of Treason and with it badly tarnish the Republican party.

Then there’s this, the last great court-stack. Numerous people have noted, but Maggie and Mike did not, even while noting that McGahn is in the middle of a SCOTUS fight:

Mr. McGahn is still the White House counsel, shepherding the president’s second Supreme Court nominee, Brett M. Kavanaugh, through the confirmation process.

William Burck, McGahn’s lawyer, is his partner-in-crime in his last great court-stack.

When Trump (presumably based on the advice of his chief court-stacker, Don McGahn) nominated Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, people (including Mitch McConnell) warned him of the danger of nominating someone with such an extensive paper record. Nevertheless, Republicans started with an assumption that that record would be made public. Until July 24, when Republicans had a private meeting and realized they had to suppress Kavanaugh’s record as White House Staff Secretary.

It is not surprising then, that on July 19, 2018, while discussing preparations for Judge Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing, Senator Cornyn — the Majority Whip and a senior member of the Judiciary Committee — said that the production of documents Judge Kavanaugh had “generated . . . authored…or contributed to” during his tenure as White House Staff Secretary should be produced to the Committee. He stated that it “just seems to be common sense.”

However, less than a week later, following a White House meeting with you on the records production on July 24, the Republican position abruptly and inexplicably shifted. Since that meeting, Senate Republicans refused to request any and all documents from Judge Kavanaugh’s three years as White House Staff Secretary, regardless of authorship. Immediately after the meeting, Senator Cornyn described requesting any Staff Secretary records as “a bridge too far.” Days later, Chairman Chuck Grassley submitted a records request to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) and omitted any of Judge Kavanaugh’s records as Staff Secretary.

Since then, William Burck has taken time away from representing Don McGahn and Reince Priebus and Steve Bannon to personally suppress lots of Kavanaugh’s records as White House Staff Secretary. And Chuck Grassley has moved up Kavanaugh’s confirmation process to make sure that some of production being slow-rolled by Don McGahn’s lawyer will not be release before Kavanaugh gets a vote on a lifetime appointment.

There’s clearly something in Kavanaugh’s record as White House Staff Secretary that might lead Susan Collins or Lisa Murkowski to vote against Kavanaugh — or make the entire nomination toxic in time for the mid-terms.

Mind you, whether Don McGahn’s failures on the topic he is supposed to be an expert on, campaign finance, contribute to getting the President’s lackeys indicted for a conspiracy may not directly relate to his last great hurrah in stacking the courts, solidifying a regressive majority on SCOTUS for a generation and with it adding someone who will suppress this investigation.

Then again it might.

Most Republicans, I suspect, will one day become willing to jettison Trump so long as they can continue stacking the courts. Trump, one day, may be expendable so long as McGahn’s expertise at stacking the court holds sway. At that level, McGahn’s political fortunes may actually conflict with Trump’s.

But not if he (and his lawyer) fuck up the last great court-stack. Not if they get blamed for failing on McGahn’s area of expertise — campaign finance — and in so doing lead to a delay in and with it the demise of the Kavanaugh confirmation.

As I disclosed last month, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.