Yesterday, Judge Amy Berman Jackson ruled that the government must turn over a memo written — ostensibly by Office of Legal Counsel head Steve Engel — to justify Billy Barr’s decision not to file charges against Donald Trump for obstructing the Mueller Investigation. The Center for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington FOIAed the memo and sued for its release. The memo itself is worth reading. But I want to consider whether, by making a nested set of false claims to hide what OLC was really up to, this opinion may pierce past efforts to use OLC to rubber stamp problematic Executive Branch decisions.

A key part of ABJ’s decision pivoted on the claims made by Paul Colburn, who’s the lawyer from OLC whose job it is (in part) to tell courts that DOJ can’t release pre-decisional OLC memos because that would breach both deliberative and attorney-client process, Vanessa Brinkmann, whose job it is (in part) to tell courts that DOJ has appropriately applied one or another of the exemptions permitted under FOIA, and Senior Trial Attorney Julie Straus Harris, who was stuck arguing against release of this document relying on those declarations. ABJ ruled that all three had made misrepresentations (and in the case of Straus Harris, outright invention) to falsely claim the memo was predecisional and therefore appropriate to withhold under FOIA’s b5 exemption.

Colburn submitted two declarations. ABJ cited this one to show that Colburn had claimed the OLC memo was designed to help Billy Barr make a decision.

Document no. 15 is a predecisional deliberative memorandum to the Attorney General, through the Deputy Attorney General, authored by OLC AAG Engel and Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General (“PADAG”) Edward O’Callaghan . . . . As indicated in the portions of the memorandum that were released, it was submitted to the Attorney General to assist him in determining whether the facts set forth in Volume II of Special Counsel Mueller’s report “would support initiating or declining the prosecution of the President for obstruction of justice under the Principles of Federal Prosecution.” The released portions also indicate that the memorandum contains the authors’ recommendation in favor of a conclusion that “the evidence developed by the Special Counsel’s investigation is not sufficient to establish that the President committed an obstruction-of-justice offense.” The withheld portions of the memorandum contain legal advice and prosecutorial deliberations in support of that recommendation. Following receipt of the memorandum, the Attorney General announced his decision publicly in a letter to the House and Senate Judiciary Committees . . . .

* * *

[T]he withheld portions of document no. 15 – the only final document at issue – are . . . covered by the deliberative process privilege. The document is a predecisional memorandum, submitted by senior officials of the Department to the Attorney General, and containing advice and analysis supporting a recommendation regarding the decision he was considering . . . . [T]he withheld material is protected by the privilege because it consists of candid advice and analysis by the authors, OLC AAG Engel and the senior deputy to the Deputy Attorney General. That advice and analysis is predecisional because it was provided prior to the Attorney General’s decision in the matter, and it is deliberative because it consists of advice and analysis to assist the Attorney General in making that decision . . . . The limited factual material contained in the withheld portion of the document is closely intertwined with that advice and analysis. [emphasis original]

Brinkmann submitted this declaration. ABJ cited it to show how Brinkmann had regurgitated the claims Colburn made.

While the March 2019 Memorandum is a “final” document (as opposed to a “draft” document), the memorandum as a whole contains pre-decisional recommendations and advice solicited by the Attorney General and provided by OLC and PADAG O’Callaghan. The material that has been withheld within this memorandum consists of OLC’s and the PADAG’s candid analysis and legal advice to the Attorney General, which was provided to the Attorney General prior to his final decision on the matter. It is therefore pre-decisional. The same material is also deliberative, as it was provided to aid in the Attorney General’s decision-making process as it relates to the findings of the SCO investigation, and specifically as it relates to whether the evidence developed by SCO’s investigation is sufficient to establish that the President committed an obstruction-of justice offense. This legal question is one that the Special Counsel’s “Report On The Investigation Into Russian Interference In The 2016 Presidential Election” . . . did not resolve. As such, any determination as to whether the President committed an obstruction-of-justice offense was left to the purview of the Attorney General. [emphasis original]

Key to this is timing: Colburn twice claimed the memo was provided to Barr before he made any decision, and based on that, Brinkmann not only reiterated that, but claimed that Mueller’s Report “did not resolve” whether Trump could be charged, which left the decision to Barr. Both were pretending a decision had not been made before this memo was written (much less completed).

In an almost entirely redacted section, ABJ explained how the first part of the memo is actually a strategy discussion (which, a redacted section seems to suggest, might have been withheld under some other FOIA exemption that DOJ chose not to claim because that would have required admitting this wasn’t legal advice), written in tandem by everyone involved, about how to best spin the already-made decision not to charge Trump.

The existence of that section contradicts the claims made by Colburn and Brinkmann, ABJ ruled.

All of this contradicts the declarant’s ipse dixit that since the Special Counsel did not resolve the question of whether the evidence would support a prosecution, “[a]s such, any determination as to whether the President committed an obstruction-of-justice offense was left to the purview of the Attorney General.” Brinkmann Decl. ¶ 11.

Then, after ABJ decided she needed to review the document over DOJ’s vigorous protests, she discovered something else (again, she redacted the discussion for now) that made her believe claims made in a filing written by Straus Harris not just to be false, but pure invention with respect to the role of Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General Edward O’Callaghan, who was privy to what Mueller was doing and the import Mueller accorded to the other OLC memo dictating that Presidents can’t be prosecuted.

And the in camera review of the document, which DOJ strongly resisted, see Def.’s Opp. to Pl.’s Cross Mot. [Dkt. # 19] (“Def.’s Opp.”) at 20–22 (“In Camera Review is Unwarranted and Unnecessary”), raises serious questions about how the Department of Justice could make this series of representations to a court in support of its 2020 motion for summary judgment:

[T]he March 2019 Memorandum (Document no. 15), which was released in part to Plaintiff is a pre-decisional, deliberative memorandum to the Attorney General from OLC AAG Engel and PADAG Edward O’Callaghan . . . . The document contains their candid analysis and advice provided to the Attorney General prior to his final decision on the issue addressed in the memorandum – whether the facts recited in Volume II of the Special Counsel’s Report would support initiating or declining the prosecution of the President . . . . It was provided to aid in the Attorney General’s decision-making processes as it relates to the findings of the Special Counsel’s investigation . . . . Moreover, because any determination as to whether the President committed an obstruction-of-justice offense was left to the purview of the Attorney General, the memorandum is clearly pre-decisional.

Def.’s Mem. in Supp. of Mot. [Dkt. # 15-2] (“Def.’s Mem.”) at 14–15 (internal quotations, brackets, and citations omitted).13

13 The flourish added in the government’s pleading that did not come from either declaration – “PADAG O’Callaghan had been directly involved in supervising the Special Counsel’s investigation and related prosecutorial decisions; as a result, in that capacity, his candid prosecutorial recommendations to the Attorney General were especially valuable.” Id. at 14 – seems especially unhelpful since there was no prosecutorial decision on the table.

I noted the problem with O’Callaghan’s role here, and argued there are probably similar problems with an OLC opinion protect Trump in the wake of Michael Cohen’s guilty plea.

In her analysis judging that an attorney-client privilege also doesn’t apply, ABJ returns to this point and expands on it, showing that in addition to Steve Engel (the head of OLC), O’Callaghan, who was not part of OLC and whom the memo never claims was involved in giving advice to Billy Barr, was also involved in generating the memo; the record also shows that the people supposedly receiving the advice, such as Rod Rosenstein, actually were involved in providing the advice, too.

While the memorandum was crafted to be “from” Steven Engel in OLC, whom the declarant has sufficiently explained was acting as a legal advisor to the Department at the time, it also is transmitted “from” Edward O’Callaghan, identified as the Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General. The declarants do not assert that his job description included providing legal advice to the Attorney General or to anyone else; Colborn does not mention him at all, and Brinkmann simply posits, without reference to any source for this information, that the memo “contains OLC’s and the PADAG’s legal analysis and advice solicited by the Attorney General and shared in the course of providing confidential legal advice to the Attorney General.” Brinkmann Decl. ¶ 16.19

The declarations are also silent about the roles played by the others who were equally involved in the creation and revision of the memo that would support the assessment they had already decided would be announced in the letter to Congress. They include the Attorney General’s own Chief of Staff and the Deputy Attorney General himself, see Attachment 1, and there has been no effort made to apply the unique set of requirements that pertain when asserting the attorney-client privilege over communications by government lawyers to them. Therefore, even though Engel was operating in a legal capacity, and Section II of the memorandum includes legal analysis in its assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the purely hypothetical case, the agency has not met its burden to establish that the second portion of the memo is covered by the attorney-client privilege

19 The government’s memorandum adds that “PADAG O’Callaghan had been directly involved in supervising the Special Counsel’s investigation and related prosecutorial decisions,” Def.’s Mem. at 14, but that does not supply the information needed to enable the Court to differentiate among the many people with law degrees working on the matter.

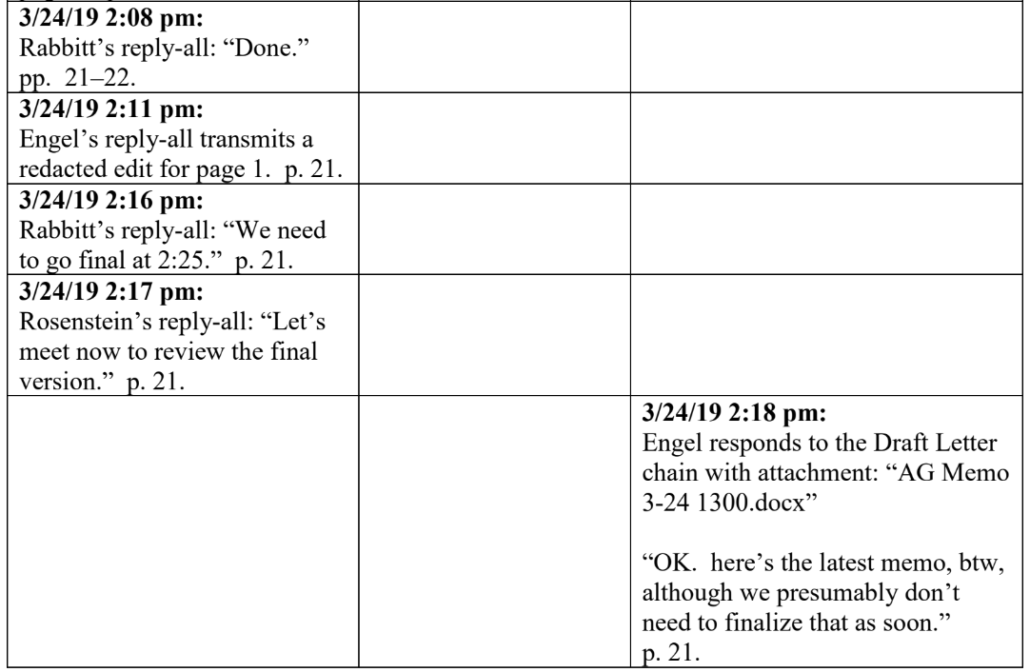

ABJ notes (and includes a nifty table in an appendix showing her work) that in fact the letter to Congress that was supposed to be based off the decision the OLC memo was purportedly providing advice about was finished first, meaning it couldn’t have informed the decision conveyed in the letter to Congress.

A close review of the communications reveals that the March 24 letter to Congress describing the Special Counsel’s report, which assesses the strength of an obstruction-of-justice case, and the “predecisional” March 24 memorandum advising the Attorney General that [redacted] the evidence does not support a prosecution, are being written by the very same people at the very same time. The emails show not only that the authors and the recipients of the memorandum are working hand in hand to craft the advice that is supposedly being delivered by OLC, but that the letter to Congress is the priority, and it is getting completed first. At 2:16 pm on Sunday, March 24, the Attorney General’s Chief of Staff advises the others: “We need to go final at 2:25 pm,” and Rod Rosenstein, the Deputy Attorney General, summons everyone to a meeting at 2:17 pm. Attachment 1 at 4. At 2:18 pm, Steven Engel in the OLC replies to this email chain related to the draft letter, and he attaches the latest version of the memo to the Attorney General, saying: “here’s the latest memo, btw, although we presumably don’t need to finalize that as soon.”

As a result, ABJ rules that this was neither pre-decisional nor candid advice from someone acting in the role of attorney given to another, and so the document must be released.

Ultimately, this is a finding that the claims made by DOJ — by Colburn, Brinkmann, and Straus Harris — have no credibility on this topic. She cites Reggie Walton’s concerns (in the BuzzFeed FOIA for the Mueller Report itself) about Billy Barr’s lies about the Mueller Report and notes that DOJ has been “disingenuous” to hide Barr’s own “disingenuous[ness].”

And of even greater importance to this decision, the affidavits are so inconsistent with evidence in the record, they are not worthy of credence. The review of the unredacted document in camera reveals that the suspicions voiced by the judge in EPIC and the plaintiff here were well-founded, and that not only was the Attorney General being disingenuous then, but DOJ has been disingenuous to this Court with respect to the existence of a decision-making process that should be shielded by the deliberative process privilege. The agency’s redactions and incomplete explanations obfuscate the true purpose of the memorandum, and the excised portions belie the notion that it fell to the Attorney General to make a prosecution decision or that any such decision was on the table at any time. [redacted]

ABJ is careful to note (in part to disincent Merrick Garland’s team from appealing this, which she has given DOJ two weeks to consider doing) that this decision is limited solely to application of the claims made before her. The often-abused b5 exemption is not dead.

The Court emphasizes that its decision turns upon the application of well-settled legal principles to a unique set of circumstances that include the misleading and incomplete explanations offered by the agency, the contemporaneous materials in the record, and the variance between the Special Counsel’s report and the Attorney General’s summary. This opinion does not purport to question or weaken the protections provided by Exemption 5 or the deliberative process and attorney-client privileges; both remain available to be asserted by government agencies – based on forthright and accurate factual showings – in the future.

But this leaves the question about what to do about all this lying — Colburn and Brinkmann and Straus Harris’ misrepresentations to protect the lies of Billy Barr and his team. Billy Barr is gone, along with Rosenstein and Engel and O’Callaghan and Brian Rabbitt (Barr’s Chief of Staff), who “colluded” (heh) to make it appear that this process wasn’t all gamed for PR value from the start.

There’s little (immediate) recourse for their lies.

But as far as I know, Colburn and Brinkmann and Straus Harris remain at DOJ, now having been caught offering misrepresentations to protect former superiors’ lies after their past equivalent representations have — for decades — been accepted unquestioningly by DC District Judges. I’ve raised concerns in the past, for example, about claims that Colburn made in 2011 (to hide drone killing opinions) and in 2016 (to hide a long-hidden John Yoo opinion on which surveillance has been based).

The reason ABJ and Reggie Walton caught DOJ in lies about the Mueller Report is not that DOJ hasn’t long been making obviously questionable claims to hide rubber stamp opinions from OLC behind the b5 exemption and obviously questionable claims to withhold documents in FOIA lawsuits. Rather, they caught DOJ in lies in this case because Billy Barr was a less accomplished (or at least more hubristic) liar than Dick Cheney (and because DOJ cannot, in this case, also make expansive claims about secrecy in the service of National Security). It is also the case that when John Yoo and David Barron rubber stamped Executive Branch excesses, they were more disciplined about creating the illusion of information being tossed over a wall to a lawyer and a decision being tossed back over the wall to the decision-maker. That was merely an illusion at least in Yoo’s case — he was both in the room where decisions were made and massaging the analysis after the fact to authorize decisions that were already made.

It would be nice to use this decision to go back and review all the dubious claims Colburn and Brinkmann have made over the years. Rudy Giuliani’s potential prosecution may offer good reason to do so in the case of Steve Engel’s equally dubious opinion withholding the Ukraine whistleblower complaint from Congress.

But at the very least, what this opinion does is show that career DOJ employees have, at least in the Bill Barr era, made less than credible claims to cover up DOJ lies, and in this case, lies about how OLC functions as a rubber stamp for Executive Branch abuse.

We may have no (immediate) recourse about the people whose abuse necessitated such misrepresentations for their protection — Barr and Rosenstein and O’Callaghan and Engel and Rabbitt — though their future legal opponents may want to keep this instance in mind.

But it is becoming a habit that when DC judges check DOJ claims in FOIA suits, those claims don’t hold up. At the very least, more scrutiny about the claims made in these nested set of declarations may finally pierce the bullshit claims made to protect OLC’s role in rubber stamping Executive Branch abuse.