John Durham’s Missing Signals (and FaceTime and WhatsApp and iPad)

As is common, the case agent for the Durham investigation against Igor Danchenko, Ryan James, was the last witness on Friday. Case agents are often used to summarize the case against a defendant and introduce boring communications records that the prosecution will rely on in the closing arguments.

As Durham cued James to describe, he spent the first nine years of his career as an FBI employee in New Haven, where Durham was, first an AUSA and then US Attorney.

Q When you finished up at the Quantico Training Academy, you would then be a first office agent as it’s sometimes referred to?

A Yes.

Q And what’s a first office agent?

A So that’s the term that you get when you graduate the academy, and it’s the first office you’re assigned to.

Q And where were you first assigned?

A New Haven, Connecticut.

Q And how long were you in New Haven, Connecticut?

A So I was there from late ’09 to September of 2018.

By description, he’s the single current or former FBI employee of five who testified at the trial (the others being Brian Auten, Kevin Helson, Amy Anderson, and Brittany Hertzog) who described no expertise in Russian counterintelligence.

James’ job was to introduce a bunch of travel and communications records that — Durham will claim on Monday — rule out the possibility that Igor Danchenko got a call from an anonymous caller, probably around July 24 or 25, 2016, someone Danchenko claimed to believe was Sergei Millian. This is the burden Durham chose to take on when he charged Danchenko with four counts — the four remaining after Judge Anthony Trenga dismissed the fifth on Friday — about whether Danchenko was lying on four different occasions in 2017 when he described what he had believed in July 2016.

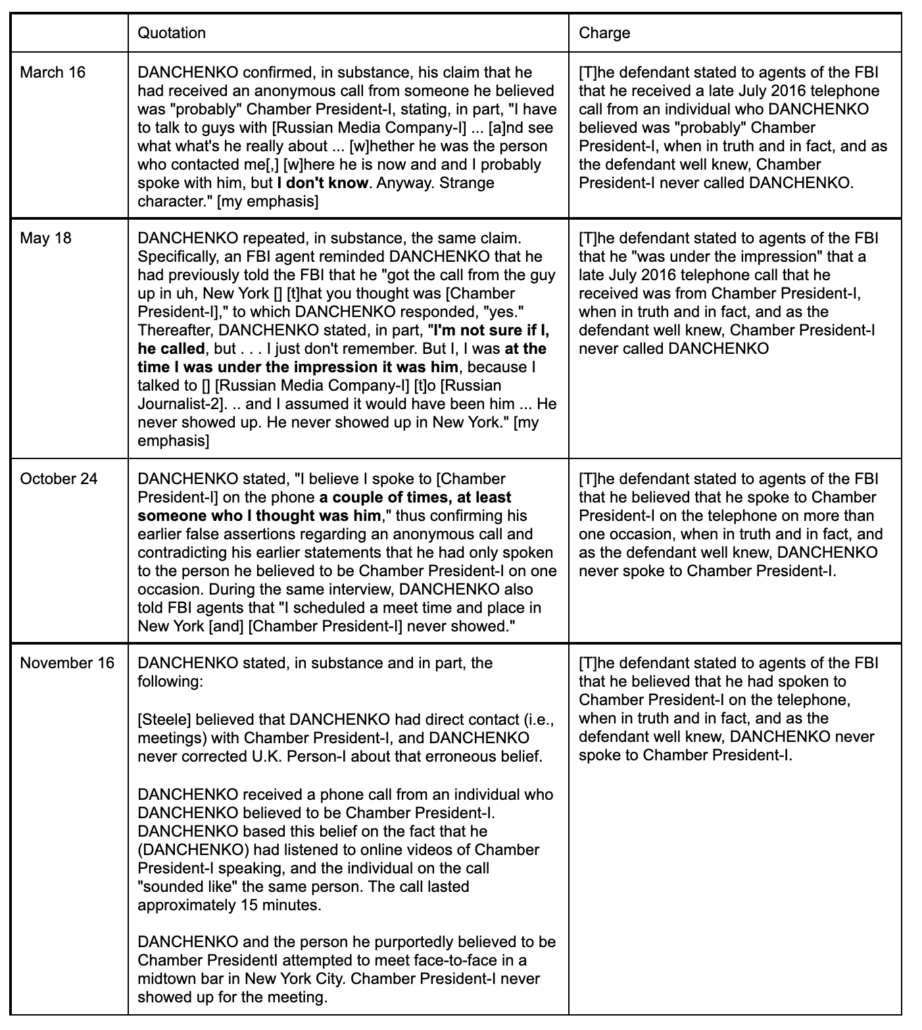

Here are those four counts as quoted in transcripts or interview reports from the indictment, and how Durham charged the alleged lie.

Durham is not proving that Danchenko lied that the person on the call was Millian. He has to prove that Danchenko lied about what he believed in about the call in 2016, five years after the interviews in question and six after the call.

At times, even Durham seems not to have understood what he got himself into by charging that Danchenko lied when he said he believed in 2016 that he thought that a call he described to the FBI came from Millian. Durham can’t just prove that Millian didn’t call Danchenko (though he has presented insufficient evidence to prove that). To rule out the possibility that Danchenko really believed a call even he described as weird came from Millian, Durham is stuck — with one exception I’ll lay out below — attempting to prove that Danchenko received no call from anyone, whether Millian or anyone else.

In an attempt to do that on Friday, Durham had James walk through how his team obtained all the records possible for the phone numbers they identified for Millian at the time (at least one, a Russian one, seems not to have been included, though exhibits aren’t available remotely).

Q And as to telephone records, would you indicate to the ladies and gentlemen of the jury what telephone records — specific telephone records that you obtained relating to Mr. Millian.

A We obtained all the records possible for the phone numbers that we had identified for Mr. Millian.

Durham had Ryan describe what sounds like a time-consuming effort to track down every single telephony call that called Danchenko’s known line in that time period in late July early August 2016.

Q Now, you told the jurors that among other things that were subpoenaed were three telephone lines that were active in 2016 for Millian, correct?

A Yes.

Q But I think you also told them that you had looked for any other number that may have been in FBI databases that would tie in some fashion to Millian, correct?

A Yes.

Q And did you compare all of those numbers to any calls going into Mr. Danchenko’s telephone number?

A Yes.

Q And the jury saw a particular record that will be in evidence reflecting the fact that Millian was providing his new Moscow number. Do you remember that? It was a plus-45 telephone number?

A Yes.

Q Did you also check that number against any incoming calls to Mr. Danchenko’s telephone line?

A Yes.

Q And what can you tell the jurors about that?

A We didn’t identify any known numbers for Sergei Millian making an incoming call to Mr. Danchenko.

They made a great show of bragging about getting records from Sergei Millian and Danchenko that (they suggested) the NY Field Office and Mueller team before them had not.

Q To your knowledge, had anybody gotten those before?

A No.

[snip]

Q Do you know if prior to you and your colleagues retrieving that information, if anybody had gone and retrieved it? Do you know?

A I do know. No, they didn’t.

But in the entire performance, neither Durham nor James described the records that would be most probative to determine if Millian called Danchenko in late July 2016: Details of LinkedIn contacts between Danchenko and Millian (probably as early as May or June) and what Danchenko’s LinkedIn page looked like when that happened. That presumed LinkedIn contact was not mentioned at all during James’ testimony.

Durham’s entire premise — that a review of incoming telephony calls to Danchenko could serve to rule out a call from Millian — is based off a claim that Millian would have no way of contacting Danchenko on anything but his telephony line, because that’s all the information Danchenko included in the signature block of the email he sent on July 21, asking to meet. Mind you, even on direct examination, when Durham had Brian Auten agree there was no mention of mobile apps in the signature block, Auten noted there was a mention of a mobile app in the body of the message: to LinkedIn.

Q And then there’s a signature block, correct?

A Correct.

[snip]

Q Is there anything anywhere in this document, Government’s Exhibit 204T, Mr. Danchenko’s initial outreach to Millian, that says anything about the use of apps?

A In the signature block, no. And the only app I believe that’s mentioned is LinkedIn, which is the last line of 204T in the letter.

Q And LinkedIn isn’t communication — verbal communication, correct?

A Not to my knowledge, no.

Q Right. So nothing in here about contact me using an app or anything of that sort?

A According to the block, no.

Durham wasn’t interested because LinkedIn, itself, does not support voice calls.

Danny Onorato emphasized the reference to LinkedIn at more length with Auten on cross.

Q. Okay. And that would be the email that Mr. Durham showed you July 21st, and that, kind of, starts off with the strange phone call, right? So the timeline is late May, right, where there’s an introduction?

A. Right.

Q. Which is Mr. Danchenko told you?

A. Yes.

Q. And then, he said in, kind of, late June or late July he reached out to Millian, right?

A. Correct.

Q. Okay. And so this is reach out, right?

A. This is — this is a July 21st —

Q. Yep.

A. — 2016, Igor Danchenko to [email protected].

Q. Okay. And what I want you to focus on, right, is that he said [As read:] “It would be interesting if it were possible to chat with you by phone or meet for coffee/beer in Washington or New York where I’ll be next week.” Right?

A. Right.

Q. “I am, myself, in Washington.” So he’s giving him alternatives as to where the meeting could take place, right?

A. Correct.

Q. Okay. I want you to focus on the last line of the email, please.

A. Yes.

Q. He said [As read:] “I sent you a request to LinkedIn. There my work is clearer.” Right?

A. Correct.

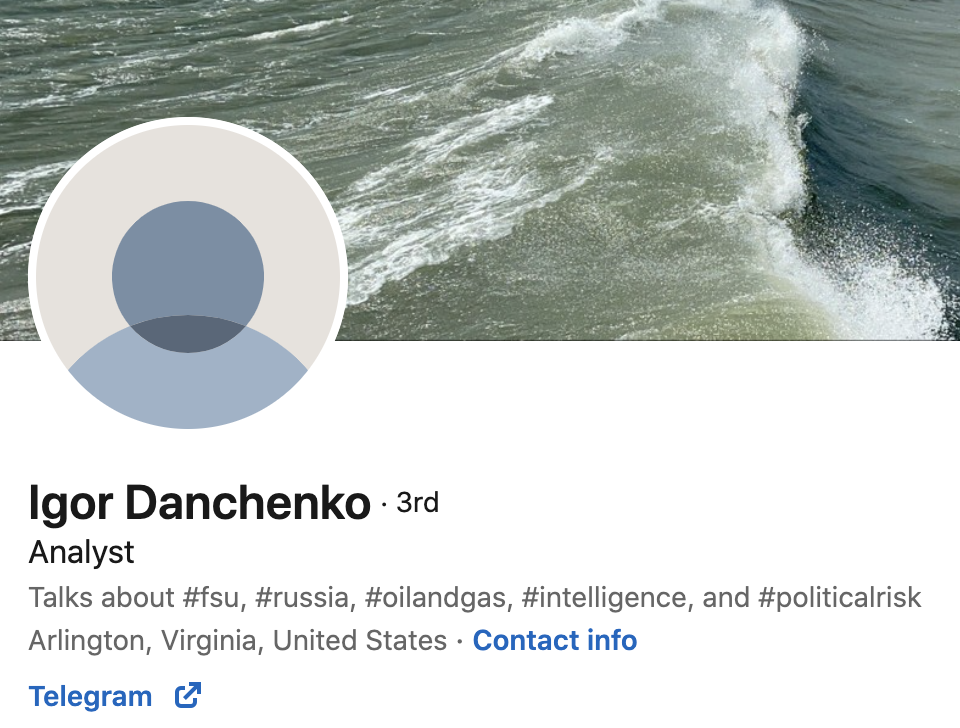

The reason Danchenko’s referral to his LinkedIn is important (aside from the prior communication that never got introduced as evidence) is because people often list all modes of communication at LinkedIn, including their mobile apps. Danchenko’s current LinkedIn bio has a link to his Telegram account.

At the time , before he started being stalked by frothers, Danchenko used at least four more mobile apps: in addition to the Telegram he still uses, WhatsApp, Viber, FaceTime, and Wickr.

Q. Okay. Thank you. Are you aware that when Mr. Danchenko spoke to the FBI he told them that he used, in this timeframe, WhatsApp, Viper, [sic] FaceTime, Wickr, and Telegram?

A. I think it would depend on what time frame you are talking about talking to the FBI.

Q. Sure. But between, let’s say, January, when you met with him, and call it July, after he’s meeting with Mr. Helson.

A. I don’t know if I would be able to rattle off all of those different things.

Q. Sure. Some of them?

A. Some of them.

Q. Okay. And, again, those apps — whether it’s one, two, three, four, or five of them — do not leave records on my Verizon cell phone bill, right?

A. I do not believe so.

If Danchenko had those apps listed on his LinkedIn in 2016, as he has Telegram listed on his LinkedIn today, then it would be readily apparent how Millian could have figured out how to call Danchenko in late July 2016: on the LinkedIn profile that Danchenko explicitly pointed him to.

The explanation from Ryan James — an FBI agent who likely worked closely with Durham since the start of his FBI career, but who claims no expertise at all in counterintelligence — about how he ruled out a call to Danchenko from Millian (much less anyone else) in 2016 did nothing to exclude mobile app calls, at all.

Short of having the cell phone Danchenko was using all the time and the devices used with the at-least four SIM cards Millian was using at the time, Durham couldn’t even begin to rule out such a call. That’s how mobile apps work, and that’s why people making spooky anonymous phone calls prefer to use apps.

Absent having the devices themselves, the FBI routinely uses Apple and Google store records to show what apps someone has downloaded onto their various phones. That’s how I know precisely when Roger Stone added ProtonMail, Signal, and WhatsApp to his phone in August, October, and (on the new phone he got after the election) November 2016: from app store records used in FBI affidavits. To make a show of figuring out what apps, besides LinkedIn, Danchenko and Millian used in common, James could have obtained records from the app stores. He didn’t describe doing that either.

But the details of the LinkedIn communications between Danchenko and Millian might have either explained or ruled out the most obvious explanation for how Millian would have known to call Danchenko on a mobile app: That Millian referred to Danchenko’s LinkedIn account, which we know he used because he used it himself to approach Papadoploulos.

When Danchenko’s lawyers lay all this out Monday, Durham will point to the single Danchenko LinkedIn communication he did introduce — a 2020 LinkedIn message confirming that he was the source for 80% of the raw intelligence in the Steele dossier.

BY MR. DURHAM: Q. Sir, with respect, then, to the Government’s Exhibit 1502, that’s a LinkedIn message, correct?

A. Correct.

Q. Now, the date of the Government’s Exhibit 1502, you indicated was, again, what?

A. It was October 11, 2020.

It’s unclear to me whether the LinkedIn messages that Durham obtained include the one(s) Danchenko sent Millian in 2016. He said he had deleted a bunch of records, including those pertaining to Millian, before first meeting with the FBI in 2017.

During cross-examination, Kevin Helson revealed that FBI themselves twice advised Danchenko to purge his phone to protect against compromise, including once after Bill Barr released his January 2017 interview materials.

Q. Okay. And, in fact, Agent Helson, once Mr. Danchenko became a confidential human source, and for good reason, you told him that he should scrub his phone, correct?

A. Yeah, at the beginning, there were two times that we had discussed that action was at the beginning to kind of mask and obfuscate his connection to Steele and any connection to us. And then after the three-day interview became public, we readdressed that as well as we assumed he would be most likely targeted from — by cyber means by the Russians.

Q. So to the extent it’s possible there were any communications that were left on his phone from the period when he was doing the reporting that later ended up being the dossier, they were likely erased?

A. Yeah, depending on how he did it.

When Danchenko submitted his objections to Durham’s exhibits on September 15, Durham had not yet identified that he planned to pull out only that October 2020 one.

The government has not identified which LinkedIn messages it seeks to introduce and Mr. Danchenko objects to admission of any messages not sent by Mr. Danchenko and objects to the inclusion of any messages not specifically admitted as evidence.

That would have been the period Durham was working on his strategy in the wake of Sergei Millian’s refusal to show up to testify under oath to any of this, the strategy preformed Friday to deny a call of any kind by reviewing only telephony calls,

The transcript reflects that only Exhibit 1502 — the October 2020 LinkedIn message — was introduced as evidence. But the stipulation mentions Exhibit 1500.

MR. DURHAM: Okay. This is in the matter of United States versus Igor Y. Danchenko, Criminal No. 1:21-cr-245, parenthesis, (AJT), close parenthesis. [As read]: It is hereby stipulated and agreed by and between the undersigned parties that, if called to testify, a records custodian from LinkedIn would testify as follows: Paragraph No. 1, Government’s Exhibits 1500 and 1502 are true and accurate copies of the contents of the LinkedIn account “Igor Danchenko” controlled by Igor Danchenko. Paragraph No. 2, Government’s Exhibits 1500 and 1502 are true and accurate copies of authentic business records of LinkedIn that were made at or near the time of the acts and events recorded in them by a person with knowledge and were prepared and kept in the course of LinkedIn’s regularly conducted business activity. And it was the regular practice of LinkedIn to make such business records, and the source of the information or the method and the circumstances of preparation are trustworthy. The parties stipulate to the authenticity of Government’s Exhibits 1500 and 1502.

All of Danchenko’s LinkedIn records that still existed in 2020 could have been available at trial, but just the October 2020 one was introduced.

There was, however, one LinkedIn message from 2016 introduced. In cross-examination of Auten, Onorato introduced the LinkedIn request that Millian sent to George Papadopoulos just days before Danchenko initially reached out to Millian on July 21.

Q. First of all, does it appear to be a LinkedIn message between George Papadopoulos and Mr. Millian?

A. Yes, it does.

Q. And the date of that is July 15th of 2016, right?

A. Correct.

Q. Okay. And just — it appears to be an email that LinkedIn is sending to Mr. Millian, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. And I’m just going to direct your attention to a specific portion of the second page. Okay?

A. Yes.

MR. ONORATO: And, Your Honor, I’m not going to talk about the —

THE COURT: All right.

BY MR. ONORATO: Q. Okay. Millian writes to George — do you see where it says, “To George”?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. So that’s Millian sending a comment to Mr. Papadopoulos, right?

A. Correct.

Q. Okay. And I want to direct your attention to the bottom of the highlighted portion where it says, “Please do not hesitate to contact me at (212) 844-9455.”

A. I see that, yes.

Q. Okay. And do you see in the last line it says, “Sent from LinkedIn for iPad”? Okay?

A. Yes, I see that.

Q. Okay. And so in this timeframe Mr. Millian is saying on the 15th that Mr. Papadopoulos can call him at that phone number that we discussed, right?

A. Correct.

Q. Okay. And so do you know that the 212 area code is from New York?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. And that’s where Mr. Millian lived, right?

A. Correct.

Q. Okay. And you also sent an iPad — a message from an iPad, right?

A. Correct.

Q. And, again, that’s a device that you can FaceTime people from that we all know, right?

A. Yes.

Q. And the one that doesn’t leave a record or footprint on a device, right? A. In terms of a record on a device.

Q. I mean a — with a cell phone carrier, like Verizon or Sprint or AT&T. A. Correct.

[snip]

Q. And so remember before when I introduced an email from Mr. Papadopoulos to Mr. Millian?

A. Yes.

Q. That came in the form of an email, didn’t it?

A. Yes, it did.

Q. And so this is, you know, him saying that I sent you a previous email, the LinkedIn email. And then I’m sending you an email on July 21st, correct?

A. I think it’s sending a request on LinkedIn.

Q. Right.

A. So I think that might be a little different than an actual email, but it’s a request.

Q. But when you get a request, it comes via email, right?

A. Yes, that does.

Millian was already in South Korea on July 15. Onorato made much of the fact, with Auten, that Durham hadn’t introduced these records. While Durham will point to the voicemail reference (which doesn’t help him as much as he thinks it does), the LinkedIn request will show that Millian wasn’t using the phone that Durham made a big deal out of being turned off. He was using an iPad.

And that detail will make the inadequacy of James’ search evident. When Durham got James to explain that he had pulled the records that would show up in a toll records report from the 917 phone number tied to Millian’s iPad. Durham almost seemed to concede you would get no phone records for telephony calls tied to an iPad.

Q You said there was a 917 area code, correct?

A Correct.

Q What were you able to determine as to that telephone number?

A It appeared that that number was assigned to an iPad.

Q Okay. And did you look at whatever records were available by way of subpoena or search warrant there?

A Yes.

James’ summary of Millian’s contacts is not online. But the LinkedIn contact with Papadopoulos would not show up on the call records Durham pulled. Its absence on James’ exhibit will serve as proof that Millian was communicating during the period for which James conducted a review in ways that would never show up in telephony records.

Danchenko’s team may have more to disprove Durham’s telephony distraction. Onorato seemed to want to say more about all this. After Durham finished questioning James on direct, Danny Onorato responded to Judge Trenga’s question about how long cross would take by hinting that he wanted to ask James questions, but he would have to convince Stuart Sears to do so first over lunch.

THE COURT: How long do you think you’ll be, Mr. Onorato?

MR. ONORATO: So Mr. Sears is going to —

THE COURT: Mr. Sears, how long do you think you’ll be? (Reporter clarification.)

MR. ONORATO: There may be no questions unless I talk him into questions.

When I read this in the transcript, I was thinking of all the questions I would want asked: about the coercion of witness testimony by threatening them with indictment, about James’ insinuation that having telephony records is more comprehensive than having actual devices — which is what Mueller’s team used to understand some of Millian’s contacts at the time. I would have asked James to describe how Durham never bothered to interview George Papadopoulos, either before Durham and Bill Barr went on a junket to Europe based off Papadopoulos’ claims, or in the wake of learning that Sergei Millian had handed him his ass.

I would have asked how he could competently claim to have ruled out a call with Danchenko without at least reviewing those LinkedIn exchanges.

But Sears convinced Onorato to holster whatever surprises they have. After lunch, Stuart Sears revealed that Onorato hadn’t talked him into questions of James at all.

THE COURT: Please be seated. Mr. Sears, any cross?

MR. SEARS: It’s a little anti-climatic, Your Honor, but I have no questions for this witness.

Rather than point out the gaping problems with James’ claimed proof that Millian didn’t call Danchenko, rather than giving Durham a chance to add to the record, they let it rest.

Damnit!

But particularly given their sustained effort to show that Durham has been withholding comms far more than Danchenko has, I expect James’ silence about LinkedIn records to be central.

So will Durham’s effort to get Auten to testify inaccurately to suggest that Danchenko had said the call from someone he believed to be Millian could only have been a telephony call.

Q. Okay. But I do want to try to correct something about what you testified about this morning. Okay?

A. Okay.

Q. And you prepared to testify with Mr. Durham and his team, right?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. And I think he asked you to look at Government Exhibit 100.

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. And when he asked you to look at Government one- — Exhibit 100, I think you may have answered that he did not mention a call app on Page 20, right, in response to his questions?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. Well, do me a favor. Look at Page 20 and then 21, And see if that refreshes your memory the first day about what Mr. Danchenko told you.

A. I apologize. Yes, it basically says — would you like me to read it?

Q. Yeah.

A. Okay. I’ll start at the middle of — middle of the last paragraph of Page 20. [As read:] “The two of them talked for a bit and the two of them tentatively agreed to meet in person in New York City at the end of July. At the end of July, Danchenko traveled with his daughter to New York but the meeting never took place and no one ever called Danchenko back. Altogether, he had only a single phone call with an individual he thought to be Millian. The call was either a cellular call or it was a communication through a phone app.”

Q. I’m sorry, what did you just say?

A. “Or it was a communication through a phone app.”

Q. Okay. So remember when Mr. Durham asked you questions this morning, right?

A. Yes.

Q. Did he omit — ask you to look at page 21 to see what Mr. Danchenko told you that day?

A. I don’t think he was omitting. I think I —

Q. Okay. And did you intentionally omit, intentionally tell the jury something wrong, right?

A. No.

Q. But the import of the testimony was that, no, he never mentioned in that first meeting it could have been a phone app, right?

A. Correct.

Q. And now we all know that that’s false, right?

A. Correct.

Q. So he did mention a mobile app?

A. That is correct.

Onorato then introduced Auten’s notes from the interview where he underlined “app.”

Q. Okay. And just for the record, again, we’re at — they’re not page-numbered, but it’s Defense Exhibit 497, and it’s Bates-stamped SCO350067270. Okay? And those appear to be — but I don’t want you to just agree with me — the interview notes from your first conversation with Mr. Danchenko. So that’s on July 24th — or January 24th. I keep saying July.

A. Yeah.

Q. Okay. I want you to look at the middle of the page.

A. Yes.

Q. And he said to you, which you wrote down at the same time and it looks like you underlined it, “Either cell phone or an app,” with an underscore, right?

A. That is correct.

Q. Those are your handwritings, right?

A. That is my handwriting, yes.

Q. And when he wrote “app,” the instant is that it’s probably an app because you’re emphasizing “app,” right?

A. I don’t necessarily know if I was emphasizing, but I did draw a line under it, yes.

Q. And you would agree that when you draw a line under something that’s generally — one of the reasons you do it is you want to emphasize —

A. It can be one of the reasons, yes.

Onorato repeated the point: Durham had introduced affirmatively false testimony about whether that call, hypothetically from Millian, may have been on a phone app.

Q. All right. And just to show the jury what you were looking at, right? A. Right. Q. So, again, despite the testimony this morning, that Mr. Danchenko did not mention a phone app, just to highlight it for you, right?

A. Correct.

Q. And so that’s the correct testimony, right?

A. Yes.

Q. And whether it was Mr. Durham’s question or whether it was your misunderstanding, you did not intentionally leave the jury with the impression, right?

A. Correct.

Q. That he didn’t say that on the first day, right?

A. Correct.

Q. But you would think as lawyers in the case that we should know the general state of the evidence?

A. Correct.

Q. And could correct that for you, right?

A. Correct.

Q. And Mr. Durham didn’t take any steps to correct your wrong answer, did he?

A. I don’t recall him correcting that.

Q. Okay. But now, I’m correcting it, right?

A. You are correcting it.

To be fair to Durham, for Onorato’s complaints here that Durham misrepresented the evidence, on several occasions, Danchenko’s lawyers have suggested that Danchenko said the call was on a mobile app, rather than it could have been. But unlike Durham and his team, Danchenko’s lawyers didn’t repeatedly elicit false testimony about what transcripts said.

None of that will be the most central part of Danchenko’s closing argument tomorrow. What will come before debunking Durham’s claim that such a call could not have taken place and showing how Durham tried to exclude records corroborating that such a call did take place is the testimony from both men who interviewed Danchenko, saying they believe him.

With Brian Auten there was some equivocation (during which Danny Onorato raised the fact that Durham had made him a subject of the investigation during the period any doubts creeped in), but ultimately he said he still does not doubt that Danchenko believed the call came from Millian, the only thing at issue in the remaining four counts.

Q. And so when you made that statement under oath before the Senate, you didn’t think he was lying to you that he had contact with Mr. Millian, right, or believed — not that he did, that he believed? A. I — I have no reason to doubt that he believed he was talking to Mr. Millian based upon what he told us in the interview. Q. Okay. I’m sorry. Once more, can you please repeat that to the jury? A. I don’t have any basis to — at the time to believe that —

[snip]

Q. So do you remember being — do you remember giving the following answer: [As read:] “On the whole, you did not see any reason to doubt the information the primary sub-source provided about who he received information from, which was the supervisory intel’s analyst focus.” Right?

A. Yes. That is from my — that’s from my OIG testimony.

Q. Right. But you said it under oath, subject to penalty of perjury?

A. Correct.

Q. And it’s true?

A. Correct.

Q. And it’s true today?

A. Correct.

Stuart Sears walked Helson first through his general opinion that Danchenko never lied to him.

Q. Agent Helson, it was no — it was no secret, during the course of your relationship with Mr. Danchenko, that there was a discrepancy between how Mr. Steele described how Mr. Danchenko represented his interactions with Mr. Millian and how Mr. Danchenko told you he actually explained his interactions?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. It was no — it was no secret. Everyone knew all along that there was a disconnect there?

A. Correct.

Q. And at no point during your entire time of meeting with Mr. Danchenko over those three years, did you ever walk away thinking that he was lying to you about anything; is that fair?

A. That’s fair.

Q. In fact, for years after your conversations with Mr. Danchenko about his anonymous phone call with the person he believed to be Mr. Millian, you would submit reports indicating that he was a reliable source?

A. Correct.

Q. And some of those reports would even mention the Millian discrepancy and you would write that you believed that Mr. Danchenko had accurately reported the information as best you could recall?

Sears then had Helson describe how, in reports in 2019 and 2020, he had dismissed the import of any inconsistencies in the Millian reporting.

Q. And this report even addresses the inconsistency regarding the Millian issue?

A. Correct.

Q. Correct? And this report that you generated says that Mr. Danchenko’s position or story on the Millian situation never changed while the motivation of others came into question, right?

A. Correct.

Q. And that’s Chris Steele?

A. That is true.

The most important testimony from Helson, though, addresses the one exception I noted above. As I noted in this post and this table above, Danchenko’s story about the Millian call, in the four charged conversations and the one with Auten, deviated from form on one occasion: on October 24, 2017.

That October 24 conversation came during the period when Auten was trying to address the discrepancies between Steele’s claims of the Millian conversations and Danchenko’s (though the FBI didn’t tell Danchenko they were interviewing Steele — they were basically playing the men off each other).

I fully expect that Durham, in an attempt to salvage at least one guilty verdict, will focus on the October 24 case and claim that the deviation from prior testimony — at a time when Danchneko was trying to fix immigration issues — was the tell that he lied.

Who knows? It might work! If he can convince the jury that the October 24 deviation was a tell that he was lying, maybe he can convince the jury that Danchenko invented the lie that he believed he had actually talked to Millian to cover up inventing a story for Durham.

That’s what he’s left with.

Which is why Helson’s note, on the back of his interview notes from that conversation, will be critically important. Explaining that he pushed Danchenko really hard on this point (this is one of the interviews for which there’s no recording and less reliable documentation), he wrote that he believed Danchenko’s response — including the inconsistent reference to two calls — was what you’d expect from particularly confrontational questioning.

Q. Okay. And you wrote — and you can close that now. And you wrote — going back to Government Exhibit 102, which was your memorandum of the interview of Mr. Danchenko — you wrote in addition to that he didn’t inquire about the nature of the questions regarding Mr. Millian, quote, “Mr. Danchenko’s responses were consistent with what would be expected during this type of questioning.”

A. Correct.

Q. And that meant that his reaction to the line of questioning did not lead you to believe he was lying to you, correct?

A. Correct.

Whether you find Danchenko’s stories credible or not, the fact of the matter is that Durham charged Danchenko with lying in these conversations in spite of the fact that his primary witnesses both attested, sometimes under oath, that they believed him.

There’s no telling what the jury will do. Durham will use testimony from a validation review to suggest that at least one person at the FBI, someone who didn’t have a personal investment in Danchenko’s success, suspected he was a GRU spy. Durham will likely argue that Auten and Helson only believe Danchenko because they’re incompetent.

Which is why, ultimately, Durham’s own evasions and failures will be central.