Four different things happened yesterday to demonstrate how differently judges presiding over the January 6 trial view it, and how little they seem to understand the intersecting nature of this investigation.

DC Circuit ignores its own language about co-conspirators and abettors

The final event was the reversal, by a per curiam panel including Karen Henderson, Judith Rogers, and Justin Walker, of Thomas Hogan’s decision to hold George Tanios pretrial.

As a reminder, Tanios is accused of both conspiring and abetting in Julian Khater’s attack on three cops, including Brian Sicknick, with some toxic substance.

I’m not going to complain about Tanios’ release. By way of comparison, Josiah Colt has never been detained, and he pled out of a conspiracy with Ronnie Sandlin and Nate DeGrave in which they, like Tanios and Khater, planned to arm themselves before traveling to DC together, and in which Sandlin and DeGrave, like Khater, are accused of assaulting cops that played a key role in successfully breaching the Capitol. The main difference is that Khater’s attack injured the three officers he targeted using a toxic spray purchased by Tanios.

It’s how the DC Circuit got there that’s of interest. Tanios had argued that Hogan had used the same language from the Munchel decision everyone else does, distinguishing those who assault or abet in assaulting police which the DC Circuit has returned to in upholding detention decisions since, and in so doing had applied a presumption of detention for those accused of assault and abetting assault.

In assessing Tanios’s risk of danger, the District Court placed too much emphasis on this sentence from Munchel: “In our view, those who actually assaulted police officers and broke through windows, doors, and barricades, and those who aided, conspired with, planned, or coordinated such actions, are in a different category of dangerousness than those who cheered on the violence or entered the Capitol after others cleared the way.” Id. at 1284.

This is only one line in a ten-page opinion written by Judge Wilkins. It is dicta. It was not quoted or adopted by Judge Katsas’s separate opinion. This line does not create a new approach for evaluating detention issues in this Circuit. It does not mandate that defendants be placed in two separate categories. It does not require a separate, harsher treatment for defendants accused of specific violent offenses. Critically, it does not create a presumption of future dangerousness and should not create a presumption of detention. Rather, it seems that the line is merely intended to remind district court judges that violence is one factor to consider in making a determination about dangerousness. [my emphasis]

The DC Circuit specifically ruled against Tanios on his claim that Hogan had misapplied Munchel.

[A]ppellant has not shown that the district court applied a presumption of detention in contravention of the Bail Reform Act and precedent, see United States v. Khater, No. 21-3033, Judgment at *2 (D.C. Cir. July 27, 2021)

They had to! As their citation makes clear, just two weeks ago, a per curiam panel of Patricia Millet, Robert Wilkins, and Ketanji Brown Jackson upheld the very same detention order (which covered both defendants), holding that the same line of the Hogan statement that Tanios pointed to did not do what both Tanios and Khater claimed it had, presume that assault defendants must be detained.

Appellant contends that the district court misapplied our decision in United States v. Munchel, 991 F.3d 1273 (D.C. Cir. 2021), by making a categorical finding, based solely on the nature of the offense charged (assaultive conduct on January 6), that no conditions of release could ever mitigate the per se prospective threat that such a defendant poses. If the district court had proceeded in that fashion and applied some sort of non-rebuttable presumption of future dangerousness in favor of detention, it would have been legal error. See id. at 1283 (“Detention determinations must be made individually and, in the final analysis, must be based on the evidence which is before the court regarding the particular defendant. The inquiry is factbound.”) (quoting United States v. Tortora, 922 F.2d 880, 888 (1st Cir. 1990)). However, while the district court stated, “Munchel delineates an elevated category of dangerousness applied [to] those that fall into the category that necessarily impose a concrete prospective threat,” the district court also explained, “I think Munchel does not set a hard-line rule. I don’t think that the categories are solely determinative, but it creates something like a guideline for the Court to follow . . . .” Detention Hr’g Tr. at 42:21-24; 43:11-13, ECF No. 26 (emphasis added). In making its ruling, the district court discussed at length the facts of this case, and expressly noted that “we have to decide whether the defendant is too dangerous based upon that conduct to be released or is not,” “every circumstance is different in every case, and you have to look at individual cases,” and that “the government may well not overcome the concrete and clear and convincing evidence requirement.” Id. at 43:8-10, 43:16-18, 43:20-21. Based on our careful review of the record, we find that the district court made an individualized assessment of future dangerousness as required by the Bail Reform Act and that appellant has not shown that the district court applied an irrefutable presumption of mandatory detention in contravention of the statute and our precedent.

Yesterday’s panel cited the earlier affirmation of the very same opinion that detained Tanios.

It’s in distinguishing Tanios where the panel got crazy. The panel could have argued that the evidence that Tanios conspired with or abetted Khater’s assault was too weak to hold him — Tanios made a non-frivolous argument that in refusing to give Khater one of the two canisters of bear spray he carried, he specifically refused to join in Khater’s attack on the cops. But they don’t mention conspiracy or abetting charges.

Instead, the DC Circuit argued that Hogan clearly erred in finding Khater’s accused co-conspirator to be dangerous.

[T]he district court clearly erred in its individualized assessment of appellant’s dangerousness. The record reflects that Tanios has no past felony convictions, no ties to any extremist organizations, and no post-January 6 criminal behavior that would otherwise show him to pose a danger to the community within the meaning of the Bail Reform Act. Cf. Munchel, 991 F.3d at 1282-84 (remanding pretrial detention orders where the district court did not demonstrate it adequately considered whether the defendants present an articulable threat to the community in light of the absence of record evidence that defendants committed violence or were involved in planning or coordinating the events of January 6).

Munchel isn’t actually a precedent here, because that decision remanded for further consideration. The DC Circuit ordered Hogan to release Tanios. Crazier still, in citing the same passage from Munchel everyone else does, the DC Circuit edited out the language referring to those who abetted or conspired with those who assaulted cops, the language used to hold Tanios. It simply ignores the basis Hogan used to hold Tanios entirely, his liability in a premeditated attack he allegedly helped to make possible, and in so doing argues the very same attack presents a danger to the community for one but not the other of the guys charged in it.

If this were a published opinion, it would do all kinds of havoc to precedent on conspiracy and abetting liability. But with two short paragraphs that don’t, at all, address the basis for Tanios’ detention, the DC Circuit dodges those issues.

Beryl Howell has no reasonable doubt about January 6

Earlier in the day, DC Chief Judge Beryl Howell grew exasperated with another plea hearing.

This time, it was Glenn Wes Lee Croy, another guy pleading guilty to a misdemeanor “parading” charge. The plea colloquy stumbled on whether Croy should have known he wasn’t permitted on the Capitol steps — he claimed, in part, that because this was his first trip to DC, he didn’t know he shouldn’t have been on the steps, even in spite of the barricades. Croy was fine admitting he shouldn’t have been in the building, though.

Things really heated up when Howell started asking Croy why he was parading (Josh Gerstein has a more detailed description of this colloquy here).

Under oath, pleading to a misdemeanor as part of a deal that prohibits DOJ from charging Croy with anything further for his actions on January 6, he made some kind of admission that Howell took to mean he was there to support Trump’s challenge to the election, an admission that his intent was the same as the intent required to charge obstruction of the vote count.

When she quizzed AUSA Clayton O’Connor why Croy hadn’t been charged with felony obstruction for his efforts to obstruct the vote certification, the prosecutor explained that while the government agreed that contextually that’s what Croy had been doing, the government didn’t find direct evidence that would allow him to prove obstruction beyond a reasonable doubt, a sound prosecutorial decision.

O’Connor is what (with no disrespect intended) might be deemed a journeyman prosecutor on the January 6 cases. He has seven cases, five of which charge two buddies or family members. Of those, just Kevin Cordon was charged with the obstruction charge Howell seems to think most defendants should face, in Cordon’s case for explicitly laying out his intent in an interview the day of the riot.

We’re here to take back our democratic republic. It’s clear that this election is stolen, there’s just so much overwhelming evidence and the establishment, the media, big tech are just completely ignoring all of it. And we’re here to show them we’re not having it. We’re not- we’re not just gonna take this laying down. We’re standing up and we’re taking our country back. This is just the beginning.

O’Connor is prosecuting Clifford Mackrell and Jamie Buteau for assault and civil disorder. But otherwise, all his cases are trespass cases like Croy’s (including that of Croy’s codefendant Terry Lindsey).

This was the guy who, with no warning, had the task of explaining to the Chief Judge DOJ’s logic in distinguishing misdemeanor cases from felonies. Unsurprisingly, it’s all about what the government thinks they can prove beyond a reasonable doubt, based on evidence like that which Cordon shared with a journalist or, just as often, what people write in their social media accounts. This process has made sense to the few of us who have covered all these cases, but like O’Connor, Howell is dealing primarily with the misdemeanor cases and my not see how DOJ appears to be making the distinction.

Howell also demanded an explanation from O’Connor in Croy’s sentencing memo why DOJ is not including the cost of the National Guard deployment in the restitution payments required of January 6 defendants.

Both according to its own prosecutorial guidelines and the practical limitations of prosecuting 560 defendants, DOJ can’t use a novel application of the obstruction statute to charge everyone arrested in conjunction with January 6 with a felony. It’s a reality that deserves a better, more formal explanation than the one O’Connor offered the Chief Judge extemporaneously.

Trevor McFadden believes a conspiracy to overthrow democracy is not a complex case

Meanwhile, the Discovery Coordinator for the entire investigation, Emily Miller, missed an opportunity to explain to Trevor McFadden the logic behind ongoing January 6 arrests.

In advance of a hearing for Cowboys for Trump founder Couy Griffin, prosecutor Janani Iyengar submitted a motion for a 60-day continuance to allow for the government to work through discovery. She brought Miller along to a status hearing to explain those discovery challenges to McFadden, who had complained about them in the past and refused to toll the Speedy Trial Act in this case. Because Iyengar recently offered Griffin a plea deal, his attorney Nick Smith was fairly amenable to whatever McFadden decided.

Not so the judge. He expressed a sentiment he has in this and other cases, that the government made a decision to start arresting immediately after the attack and continues to do so. “There seems to be no end in sight,” McFadden complained, suggesting that if DOJ arrested someone in three months who offered up exculpatory evidence that affected hundreds of cases, those would have to be delayed again. In spite of the fact that several prosecutors have explained that the bulk of the evidence was created on January 6, McFadden persists in the belief that the trouble with discovery is the ingestion of new evidence with each new arrest.

Miller noted that the government could start trials based on the Brady obligation of turning over all exculpatory evidence in their possession, so future arrests wouldn’t prohibit trials. The problem is in making the universe of video evidence available to all defense attorneys so they have the opportunity of finding evidence to support theories of defense (such as that the cops actually welcomed the rioters) that would require such broad review of the video.

McFadden then suggested that because Griffin is one of the rare January 6 defendants who never entered the Capitol, Miller’s team ought to be able to segregate out an imagined smaller body of evidence collected outside. “Were that it were so, your honor,” Miller responded, pointing out that there were thousands of hours of surveillance cameras collected from outside, the police moved in and outside as they took breaks or cleaned the bear spray from their eyes so their Body Worn Cameras couldn’t be segregated, and the Geofence warrant includes the perimeter of the Capitol where Griffin stood.

McFadden then said two things that suggested he doesn’t understand this investigation, and certainly doesn’t regard the attack as a threat to democracy (he has, in other hearings, noted that the government hasn’t charged insurrection so it must not have been one). First, he complained that, “In other cases,” the government had dealt with a large number of defendants by giving many deferred prosecutions or focusing just on the worst of the worst, a clear comparison to Portland that right wingers like to make. But that’s an inapt comparison. After noting the data somersaults one has to do to even make this comparison, a filing submitted to Judge Carl Nichols in response to a selective prosecution claim from Garret Miller explained the real differences between Portland and January 6: There was far less evidence in the Portland cases, meaning prosecutions often came down to the word of a cop against that of a defendant and so resulted in a deferred prosecution.

This comparison fails, first and foremost, because the government actually charged nearly all defendants in the listed Oregon cases with civil-disorder or assault offenses. See Doc. 32-1 (Attachments 2-31). Miller has accordingly shown no disparate treatment in the government’s charging approaches. He instead focuses on the manner in which the government ultimately resolved the Oregon cases, and contrasts it with, in his opinion, the “one-sided and draconian plea agreement offer” that the government recently transmitted to him. Doc. 32, at 6. This presentation—which compares the government’s initial plea offer to him with the government’s final resolution in 45 hand-picked Oregon cases—“falls woefully short of demonstrating a consistent pattern of unequal administration of the law.”3 United States v. Bernal-Rojas, 933 F.2d 97, 99 (1st Cir. 1991). In fact, the government’s initial plea offer here rebuts any inference that that it has “refused to plea bargain with [Miller], yet regularly reached agreements with otherwise similarly situated defendants.” Ibid.

More fundamentally, the 45 Oregon cases serve as improper “comparator[s]” because those defendants and Miller are not similarly situated. Stone, 394 F. Supp. 3d at 31. Miller unlawfully entered the U.S. Capitol and resisted the law enforcement officers who tried to move him. Doc. 16, at 4. He did so while elected lawmakers and the Vice President of the United States were present in the building and attempting to certify the results of the 2020 Presidential Election in accordance with Article II of the Constitution. Id. at 2-3. And he committed a host of federal offenses attendant to this riot, including threatening to kill a Congresswoman and a USCP officer. Id. at 5-6. All this was captured on video and Miller’s social-media posts. See 4/1/21 Hr’g Tr. 19:14-15 (“[T]he evidence against Mr. Miller is strong.”). Contrast that with the 45 Oregon defendants, who—despite committing serious offenses—never entered the federal courthouse structure, impeded a congressional proceeding, or targeted a specific federal official or officer for assassination. Additionally, the government’s evidence in those cases often relied on officer recollections (e.g., identifying the particular offender on a darkened plaza with throngs of people) that could be challenged at trial—rather than video and well-documented incriminating statements available in this case. These situational and evidentiary differences represent “distinguishable legitimate prosecutorial factors that might justify making different prosecutorial decisions” in Miller’s case. Branch Ministries, 211 F.3d at 145 (quoting United States v. Hastings, 126 F.3d 310, 315 (4th Cir. 1997)); see also Price v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, 865 F.3d 676, 681 (D.C. Cir. 2017) (observing that a prosecutor may legitimately consider “concerns such as rehabilitation, allocation of criminal justice resources, the strength of the evidence against the defendant, and the extent of a defendant’s cooperation” in plea negotiations) (brackets and citation omitted).

3 Miller’s motion notably omits reference to the remaining 29 Oregon cases in his survey, presumably because the government’s litigation decisions in those cases do not conform to his inference of selective treatment. [my emphasis]

McFadden ended with one of his most alarming comments. He said something to the effect of, he doesn’t feel that the January 6 investigation was a complex type of case akin to those (often white collar cases) where a year delay before trial was not that unusual.

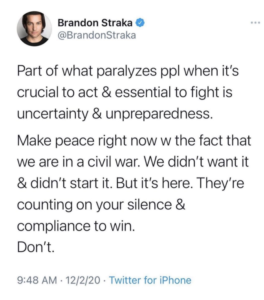

This was a fairly breathtaking comment, because it suggests that McFadden sees this event as the magical convergence of thousands of criminals at the Capitol rather than the result of a sustained conspiracy to get a mass of bodies to the building, a conspiracy that started at least as early as the days after the election. While McFadden’s highest profile January 6 case is a sprawling assault case against Patrick McCaughey and others (the one that trapped Officer Daniel Hodges in the Capitol door), this view seems not to appreciate some larger investigative questions pertinent to some of his other defendants. For example, what happened to the laptops stolen from various offices, including the theft that Brandon Fellows may have witnessed in Jeff Merkley’s office. Did America First engaged in a conspiracy to gets its members, including Christian Secor, to the Capitol (and did a huge foreign windfall that Nick Fuentes got days before the insurrection have anything to do with that). What kind of coordination, if any, led a bunch of Marines to successfully open a second front to the attack by opening the East Doors also implicates Secor’s case. One of the delays in Griffin’s own case probably pertained to whether he was among the Trump speakers, as members of the 3-Percenter conspiracy allegedly were, who tied their public speaking role to the recruitment of violent, armed rioters (given that he has been given a plea offer, I assume the government has answered that in the negative).

It has become increasingly clear that one of the visible ways that DOJ is attempting to answer these and other, even bigger questions, is to collect selected pieces of evidence from identifiable trespassers with their arrest. For example, Anthony Puma likely got arrested when he did because he captured images of the Golf Cart Conspiracy with his GoPro. He has since been charged with obstruction — unsurprisingly, since he spoke in detailed terms about preventing the vote certification in advance. But his prosecution will be an important step in validating and prosecuting the larger conspiracy, one that may implicate the former President’s closest associates.

This is white collar and complex conspiracy investigation floating on top of a riot prosecution, one on which the fate of our democracy rests.

Melody Steele-Smith evaded the surveillance cameras

A report filed yesterday helps to explain the import of all this. Melody Steele-Smith was arrested within weeks of the riot on trespass charges, then indicted on trespass and obstruction charges. She’s of particular interest in the larger investigation because — per photos she posted on Facebook — she was in Nancy Pelosi’s office and might be a witness to things that happened there, including the theft of Pelosi’s laptop.

At a hearing last week, the second attorney who has represented her in this case, Elizabeth Mullin, said she had received no discovery, particularly as compared to other January 6 defendants. So the judge in that case, Randolph Moss, ordered a status report and disclosure of discovery by this Friday.

That status report admits that there hasn’t been much discovery, in particular because, aside from the surveillance photos used in her arrest warrant, the government hasn’t found many images of Steele-Smith in surveillance footage.

The United States files this memorandum for the purpose of describing the status of discovery. As an initial matter, the government has provided preliminary discovery in this case. On or about June 4, 2021, the government provided counsel for defendant preliminary discovery in this matter. This production had been made previously to the defendant’s initial counsel of record. Counsel for defendant received the preliminary production that had been provided to previous counsel. This preliminary production included the FBI 302 of defendant’s sole interview, the recorded interview of defendant which formed the basis of the aforementioned FBI 302, over one thousand pages of content extracted from defendant’s Facebook account, and thirty-nine photographs confiscated from defendant’s telephone.

The government is prepared to produce an additional discovery production no later than August 13, 2021. The production will include additional items that have been obtained by the government from the FBI. These items include, additional FBI investigative reports and the Facebook search warrant dated January 21, 2021. The FBI has provided the government with the full extent of the materials in its possession. While these items are few in number, the government is continuing to review body worn camera footage in an attempt to locate the defendant. Camera footage will be provided if it is located. The government has been diligent in its efforts to obtain all discoverable items in possession of the FBI.

That still leaves a thousand Facebook pages and 39 photos, some of them taken at a key scene in the Capitol a scene that — given the evidence against Steele-Smith and in other cases — is a relative blind spot in the surveillance of the Capitol. The interview described here is not reflected in her arrest warrant, and so may include non-public information used to support the obstruction case.

Beryl Howell might argue this is sufficient evidence to prove the government’s obstruction case. Trevor McFadden might argue that this case can’t wait for more video evidence obtained from future arrestees of what Steele-Smith did while “storm[ing] the castle” (in her own words), including the office of the Speaker of the House. But the theft of the Pelosi laptop — including whether Groypers like Riley Williams were involved — remains unsolved.

If a single terrorist with suspect ties to foreign entities broke into the office of the Speaker of the House and stole one of her laptops, no one would even think twice if DOJ were still investigating seven months later. But here, because the specific means of investigation include prosecuting the 1,000 people who made that break-in possible, there’s a push to curtail the investigation.

I don’t know what the answer is because the Speedy Trial issues are very real, particularly for people who are detained. But I do know it’s very hard for anyone to get their mind around this investigation.