The Chapo Secrets the Press Should Be Squealing About

Update: For those who haven’t already read it, this post, Sean Penn, Intelligence Dangle, will help explain this one.

The frenzy among journalists about Sean Penn’s Chapo Guzmán story has continued over two days now. As is typical of press frenzies, it is largely divorced from the actual details involved.

So I’d like to revisit the question of what Penn may have withheld from his story — because the press is frenzying over the wrong thing.

The Rolling Stone says “Some names have had to be changed, locations not named.” As with the rest of the disclosure statement, the language here is notable, as the passive voice avoids saying not only whose names got withheld, but who made the decision to withhold them.

Subsequent reporting, handed over from Mexican intelligence, makes clear that authorities know those details pertaining to Chapo’s side. Kate del Castillo and Penn first went to Guadalajara, where they stayed in Villa Ganz. From there they were driven to an air strip in Tepic, Nayarait, where they were flown in a private plane to Cosalá, Sinaloa and then driven to a location on the border of Durango. Del Castillo’s primary interlocutor is named as Andrés Granados Flores, though she also met with Óscar Manuel Gómez Núñez (the latter of whom was arrested weeks after the Penn meeting as the mastermind of Chapo’s escape last year).

Penn’s own narrative makes it clear that both Alfredo and Iván Guzmán, Chapo’s sons, attended the meeting. The only Sinaloans whose names he may have changed were “Alonzo” (who is likely to be Granados) and, possibly, some bodyguard type in Chapo’s presence, Rodrigo. He may have protected the identity of others, but not by changing their name, as the disclosure describes.

In other words, the key players in this story whose names were changed were not Chapo’s men, but the two men who linked him with del Castillo in the first place, Espinoza (whom I call Spiny) and El Alto. It is true Rolling Stone did not name locations; at it turns out, Mexican authorities were following so closely, with cameras, anyway, hiding the locations didn’t help Chapo much.

Curiously, those two men, Spiny and El Alto, don’t show up in the pictures released to the press, even though the caption on one describes them as del Castillo, Penn, and “their companions.”

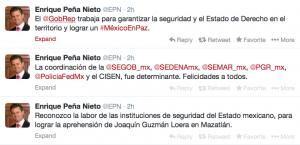

So the Rolling Stone protected these mysterious interlocutors more religiously than they did Chapo’s family. As Jann Wenner described to the NYT (which, of course, played a complicit role in magnifying all this), Chapo didn’t actually have an interest in “editing” Penn’s work.

Mr. Guzmán, he said, did not speak English and seemed to have little interest in editing Mr. Penn’s work. “In this case, it was a small thing to do in exchange for what we got,” Mr. Wenner said.

But there is one detail, in addition to the locations, that Penn did withhold, purportedly at the request of Chapo, one which I haven’t seen any participant in the press frenzy complain about.

He cites (but asks me not to name in print) a host of corrupt major corporations, both within Mexico and abroad. He notes with delighted disdain several through which his money has been laundered, and who take their own cynical slice of the narco pie.

This is particularly odd, given that the complicity of Americans, including our banks, is one theme of Penn’s own framing of this adventure.

The laws of conscience, which we pretend to be derived from nature, proceed from custom.” —Montaigne

[snip]

Still, today, there are little boys in Sinaloa who draw play-money pesos, whose fathers and grandfathers before them harvested the only product they’d ever known to morph those play pesos into real dollars. They wonder at our outrage as we, our children, friends, neighbors, bosses, banks, brothers and sisters finance the whole damn thing.

If Penn is sincere in his stated desire to end the war on drugs, ending the profits for American banks tied to illicit trafficking would need to be one of the first steps.

But he doesn’t name those companies that are laundering Chapo’s money, which will continue to be laundering Sinaloa cartel money even as Guzmán gets removed from the network.

Of course, Spiny and El Alto probably share Chapo’s desire to keep those names out of print, in part because they’re part of the power structure that the banks bolster, in part because banks sometimes narc on their customers to save their own hides.

But it’s funny how the press, too, seems uninterested in learning the names of the banks that continue to prop up both our own country’s power structure as well as facilitate traffickers like Guzmán.