Thanks to those who’ve donated to help defray the costs of trial transcripts. Your generosity has funded the expected costs. If you appreciate the kind of coverage no one else is offering, we’re still happy to accept donations for this coverage — which reflects the culmination of eight months work.

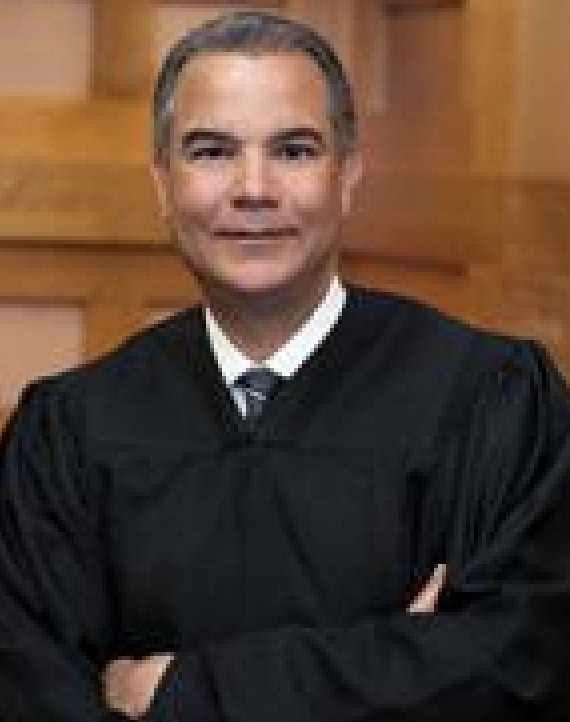

The jury in the Michael Sussmann case will return to work this morning. They deliberated for some period on Friday (I’m not sure whether how long they deliberated has been reported). But the jury was unable to get questions answered or a verdict accepted after Judge Christopher Cooper left for the long holiday at 2:30PM. Even if the jury ends up finding Jim Baker’s testimony unreliable — which would likely be the quickest way to come to a verdict one way or another — I would expect it to take the jury a bit of time to sort through the centrality of his testimony to the charges.

So while we wait, I want to catalog how Durham’s team blew off just about every adverse decision Cooper made against them.

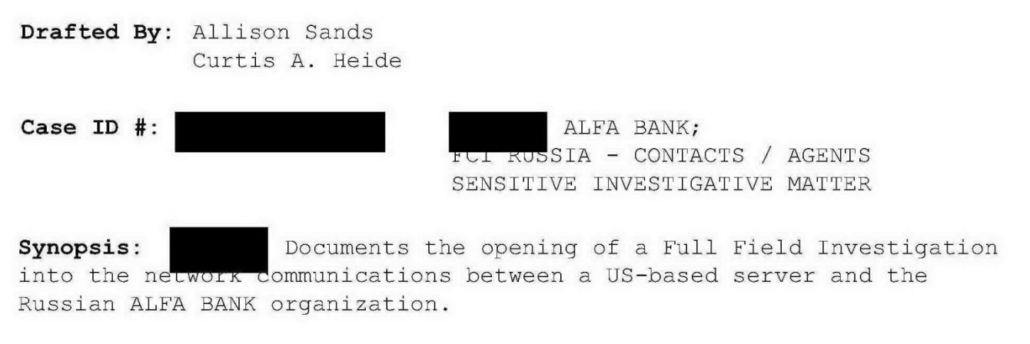

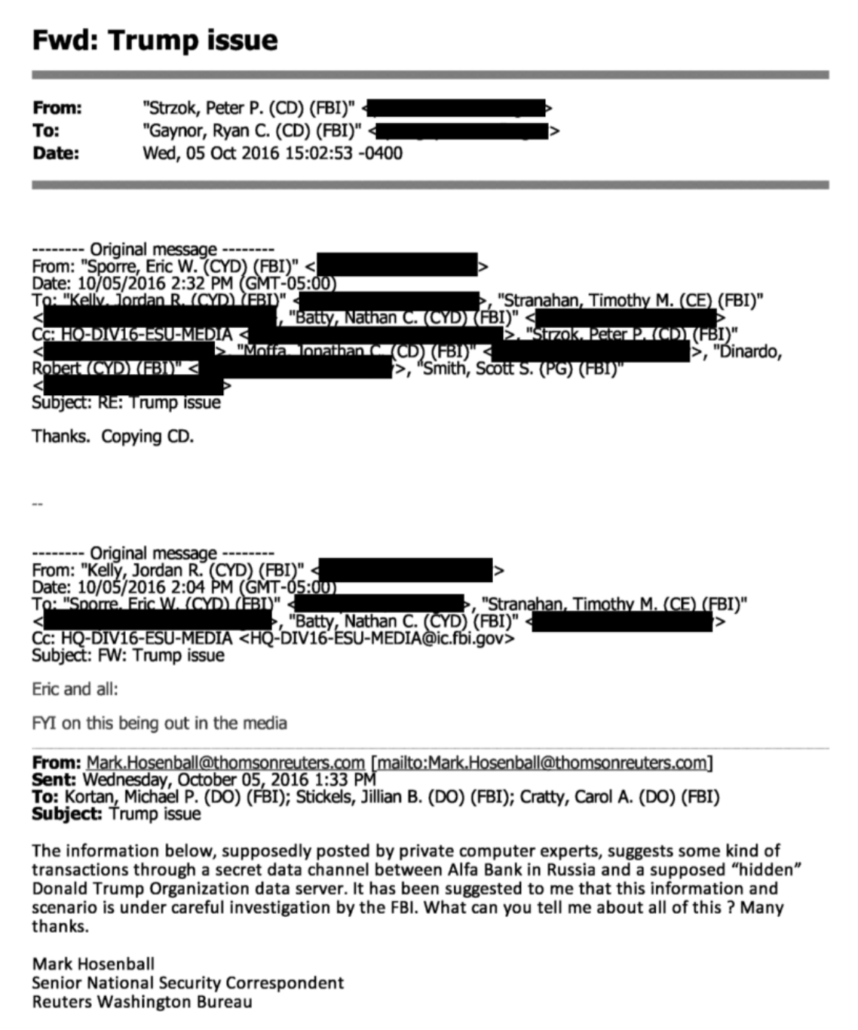

1. Delayed Request for Privileged Material

As I laid out in this post, Cooper ruled that a bunch of the emails over which the Democrats had originally claimed privilege were not. But because Durham waited so long to request a review of the privileged documents, Cooper ruled Durham could not use the emails at trial.

In cross-examination of Fusion’s tech person, Laura Seago, DeFilippis used the content of one of those emails that apparently discussed hiding her Fusion affiliation from Tea Leaves. (I laid out this exchange in this post.)

MR. DeFILIPPIS: So we have an issue with regard to Ms. Seago’s testimony. The government followed carefully Your Honor’s order with regard to the Fusion emails that were determined not to be privileged but that the government had moved on.

As Your Honor may recall, there was an email in there in which Ms. Seago talks very explicitly about seeking to approach someone associated with the Alfa-Bank matter and concealing her affiliation with Fusion in the email. When we asked her broadly whether she ever did that, she definitively said no when I, you know, revisited it with her. So it raises the prospect that she may be giving false testimony.

And so we were — you know, I considered trying to refresh her with that, but I didn’t understand that to be in line with Your Honor’s ruling. So the government is — we’d like to consider whether we should be — we’d like Your Honor to consider whether we should be able to at least recall her and refresh her with that document?

THE COURT: I don’t remember that question, but the subject matter was concealing Fusion or her identities in conversations with the press. If I recall correctly, that email related to “tea leaves,” correct?

After repeatedly asking Seago whether she had hidden her affiliation from the media, he asked about this email, catching Seago in a gotcha (though both Judge Cooper and Sussmann lawyer Sean Berkowitz took the question, as Seago seemed to, to relate to outreach to the press).

After setting his perjury trap, DeFilippis immediately tried to recall Seago onto the stand to delve into the content of this email. In this case, Judge Cooper ruled that DeFilippis had waived his opportunity to do so.

THE COURT: Well, I think the time to have asked the Court whether using the document to refresh was consistent with the order was before she was tendered and dismissed. So I think you waived your opportunity. All right? So we’re going to move on.

2. Non-Expert Expert Testimony

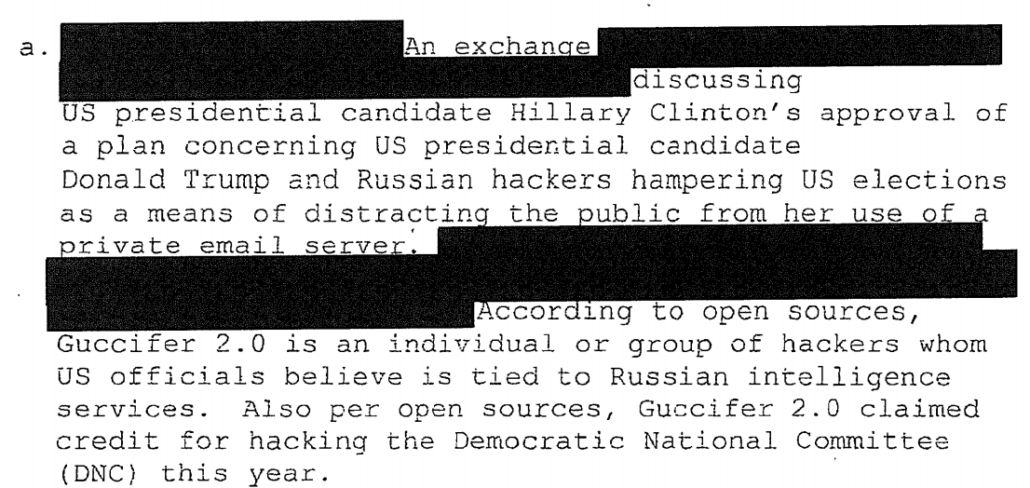

One of the most contentious arguments leading up to trial was Durham’s belated attempt to use an expert witness, ostensibly to discuss the technical complexities of DNS and Tor at the heart of the case (topics which prosecutors had witnesses explain over and over in as much detail as their nominal expert witness David Martin did), to address the accuracy of the research on the DNS anomaly.

This was an attempt to lead the jury to believe the anomaly was fabricated by Rodney Joffe and the researchers, in spite of the fact that Durham obtained plenty of evidence it was not.

On April 25, Judge Cooper ruled that Durham could have an expert discuss the technicalities of the data, but could only raise the accuracy if Sussmann did so himself.

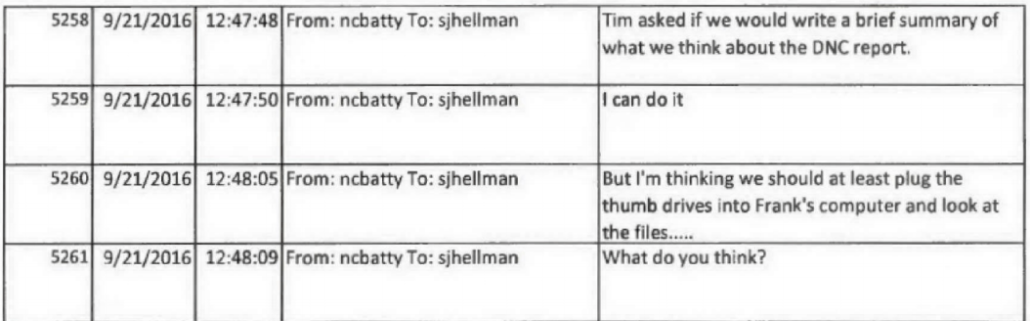

Then on May 6, Durham attempted to expand that ruling by asking the expert to address materiality. In discussions the morning of opening arguments that focused entirely on the testimony of non-DNS expert Scott Hellman, not the nominal expert on DNS David Martin, Cooper prohibited Martin’s discussion of spoofing. (I describe these discussions here.)

Ironically, this was all supposed to be about visibility, the import of understanding how much DNS traffic a researcher could access to the quality of that researcher’s work. In Hellman’s own analysis — for which he fairly demonstrably did not review the data that Sussmann shared with the FBI very closely — he showed no curiosity about the issue.

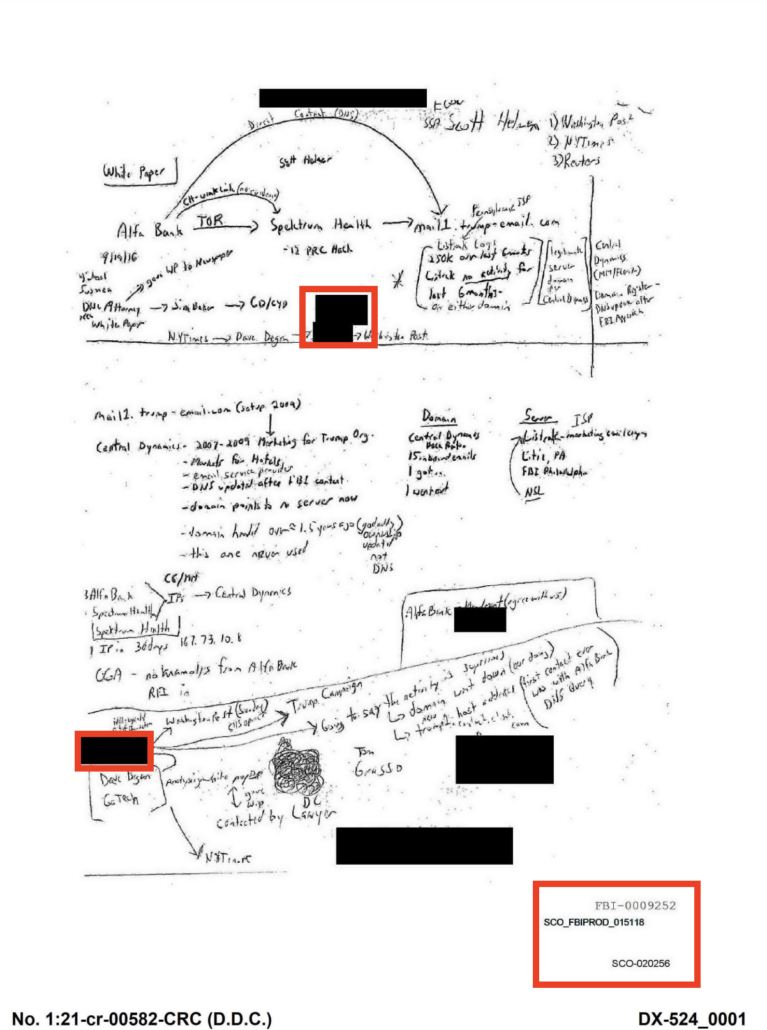

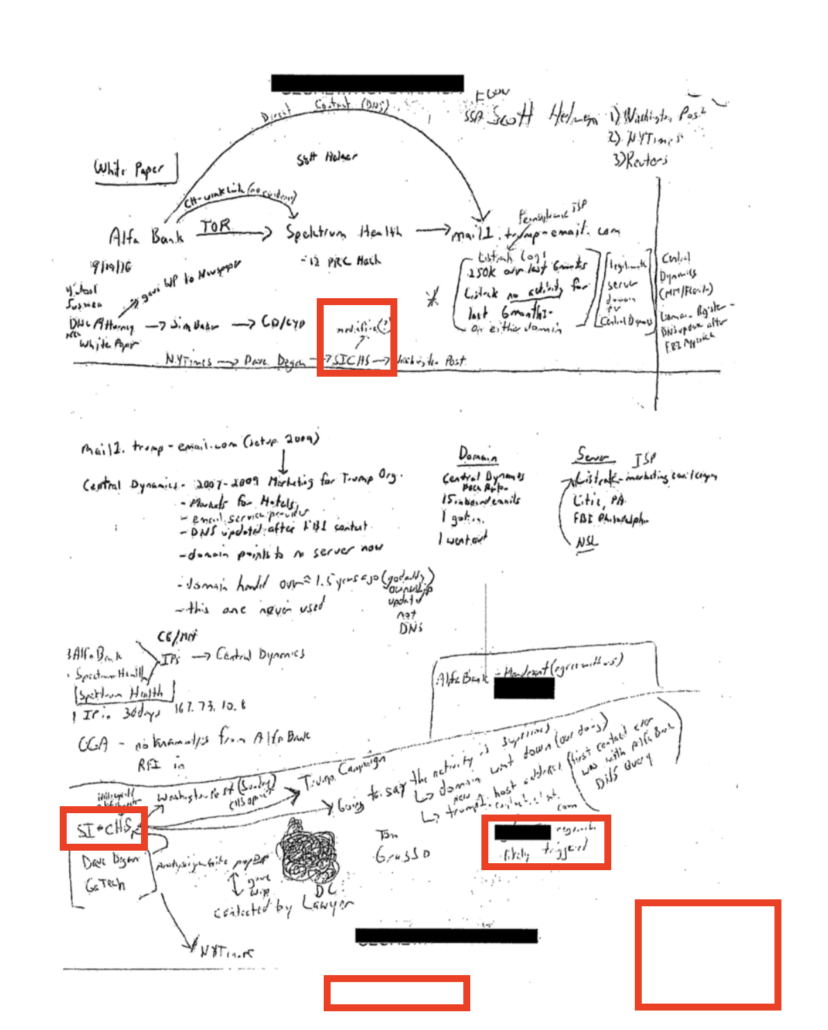

Searched “…global nonpublic DNS activity…” (unclear how this was done) and discovered there are (4) primary IP addresses that have resolved to the name “mail1.trump-email.com”. Two of these belong to DNS servers at Russian Alfa Bank. [my emphasis]

Nevertheless, DeFilippis used this nested set of witnesses as an opportunity to get Hellman — who admitted he had only a basic understanding of DNS, who didn’t review the data very closely, and who formed his initial conclusion in about a day — to comment on the methodology of the researchers.

Q. And what, if anything, did you conclude about whether you believed the authors of the paper or author of the paper was fairly and neutrally conducting an analysis? Did you have an opinion either way?

MR. BERKOWITZ: Objection, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Basis?

MR. BERKOWITZ: Objection on foundation. He asked him his opinion. He’s not qualified as an expert for that.

THE COURT: I’ll overrule it.

A. Sorry, can you please repeat the question?

Q. Sure. Did you draw a conclusion one way or the other as to whether the authors of this paper seemed to be applying a sound methodology or whether, to the contrary, they were trying to reach a particular result? Did you —

A. Based upon the conclusions they drew and the assumptions that they made, I did not feel like they were objective in the conclusions that they came to.

Q. And any particular reasons or support for that?

A. Just the assumption you would have to make was so far reaching, it didn’t — it just didn’t make any sense.

This is precisely the kind of opinion that Cooper had prohibited from an actual expert, admitted from someone whose own shoddy analysis became a recurrent theme for the defense.

3. Hearsay Clinton Tweet

DeFilippis’ efforts to get excluded information introduced was still more brazen with hearsay materials.

On May 7, Judge Cooper issued his initial ruling on which parts of Durham’s conspiracy theory could be admitted at trial. In general, Cooper permitted the introduction of Fusion GPS emails with the press about the Alfa Bank allegations, all of which post-date Sussmann’s alleged lie. He excluded all but one of the emails between Rodney Joffe and the researchers (more on the exception below).

Cooper equivocated wildly about a tweet sent out under Hillary Clinton’s name in response to the Franklin Foer story on the anomaly. In a hearing on April 27, he excluded it as hearsay.

THE COURT: All right. The Clinton Campaign Tweet, the Court will exclude that as hearsay. To the extent that the government believes that it offers some connection to the campaign and an attorney-client relationship, it’s likely duplicative of other evidence, so the Tweet will not come in.

In a pre-trial hearing on May 9 (after he had issued his order on motions in limine), Cooper explained he was revisiting the decision.

But I guess my question, as I have thought more about this, given the sort of two competing theories of the case and two narratives laid out in the Court’s ruling on the motion in limine, is whether it is relevant not for the truth, but to show the campaign’s connection to the alleged public relations effort to play stories regarding the Alfa-Bank data with the press and that therefore it is sort of context for the Government’s motive theory, that Mr. Sussmann sought to conceal that effort, as well as the campaign’s general connection to that effort.

After Sussmann lawyer Sean Berkowitz explained that the defense would not contest that the campaign wanted a story out there, Cooper opined that would make the tweet cumulative.

Well, if that’s going to be the case, and he’s not contesting that he was representing the campaign in connection with that effort, isn’t the tweet cumulative? It’s icing on the cake. Right?

DeFilippis claimed that without the tweet they would have no evidence about how the campaign worked the press on this issue (even though both Marc Elias, called as a government witness, and Robby Mook, who was originally listed as a government witness, eventually testified to the issue on the stand). After Judge Cooper said he would reserve his decision, Berkowitz noted that in fact, DeFilippis planned to use the tweet to claim the campaign wanted to go to the FBI when the testimony at trial (from both Elias and Mook) would establish that going to the FBI conflicted with the campaign’s goals.

[T]hey are offering the tweet for the truth of the matter, that that’s what the campaign desired and wanted and that it was a accumulation of the efforts.

Number one, it’s not the truth; and in fact, it’s the opposite of the truth. We expect there to be testimony from the campaign that, while they were interested in an article on this coming out, going to the FBI is something that was inconsistent with what they would have wanted before there was any press. And in fact, going to the FBI killed the press story, which was inconsistent with what the campaign would have wanted.

And so we think that a tweet in October after there’s an article about it is being offered to prove something inconsistent with what actually happened.

Then, after both Elias and Mook had testified that they had not sanctioned Sussmann going to the FBI, DeFilippis renewed his assault on Cooper’s initial exclusion, asking to introduce it through Mook’s knowledge that the campaign had tried to capitalize on the Foer story.

Having ruled in the past that the tweet was cumulative and highly prejudicial, Cooper nevertheless permitted DeFilippis to introduce the tweet if he could establish that Mook knew that the campaign tried to capitalize on the Foer story.

But Cooper set two rules: The government could not read from the tweet and could not introduce the part of the tweet that referenced the FBI investigation. (I explained what DeFilippis did at more length in this post.)

THE COURT: All right. Mr. DeFilippis, if you can lay a foundation that he had knowledge that a story had come out and that the campaign decided to issue the release in response to the story, I’ll let you admit the Tweet. However, the last paragraph, I agree with the defense, is substantially more prejudicial than it is probative because he has testified that had neither — he nor anyone at the campaign knew that Mr. Sussmann went to the FBI, no one authorized him to go to the FBI, and there’s been no other evidence admitted in the case that would suggest that that took place. And so this last paragraph, I think, would unfairly suggest to the jury, without any evidentiary foundation, that that was the case. All right?

MR. DeFILIPPIS: Your Honor, just two brief questions on that.

THE COURT: Okay.

MR. DeFILIPPIS: Can we — so can we use — depending on what he says about whether he was aware of the Tweet or the public statement, may we use it to refresh him?

THE COURT: Sure. Sure.

MR. DeFILIPPIS: Okay. And then, as to the last paragraph, could it be used for impeachment or refreshing purposes as well in terms of any dealings with the FBI?

THE COURT: You can use anything to refresh.

MR. DeFILIPPIS: Okay.

THE COURT: But we’re not going to publish it to the jury. We’re not going to read from it. And let’s see what he says. [my emphasis]

Having just been told not to read the tweet, especially not the part about the FBI investigation, DeFilippis proceeded to have Mook do just that.

The exhibit of the tweet that got sent to the jury had that paragraph redacted and that part of the transcript was also redacted. But, predictably, the press focused on little but the tweet, including the part that Cooper had explicitly forbidden from coming into evidence.

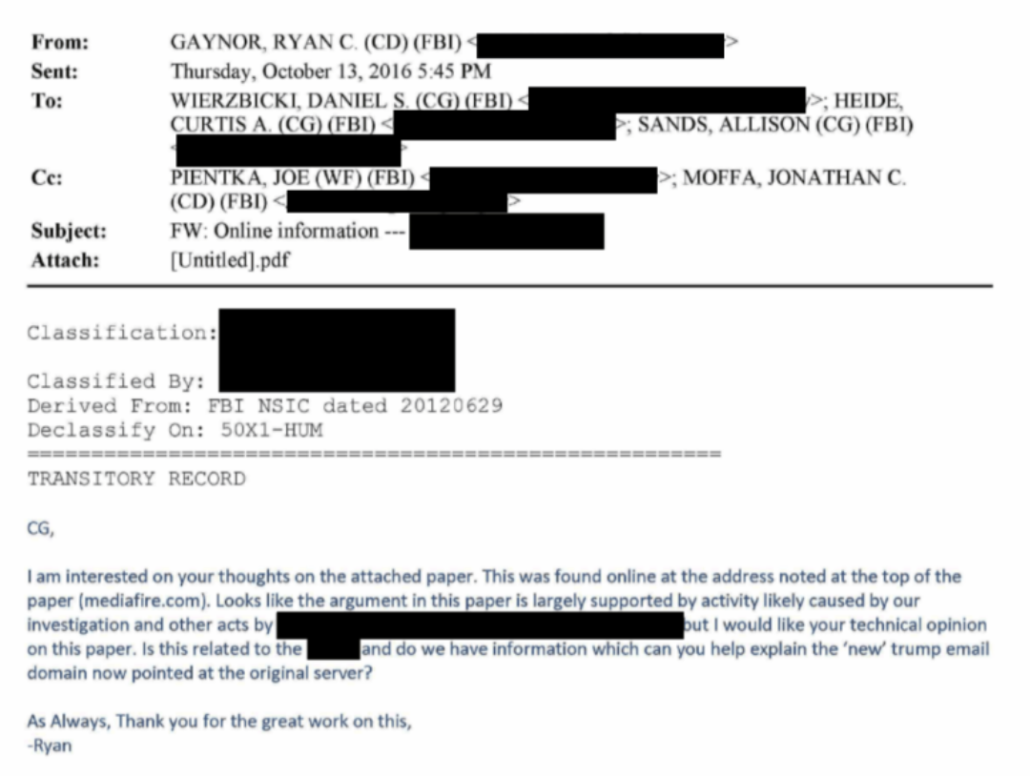

4. Hearsay about Joffe’s Request for Feedback

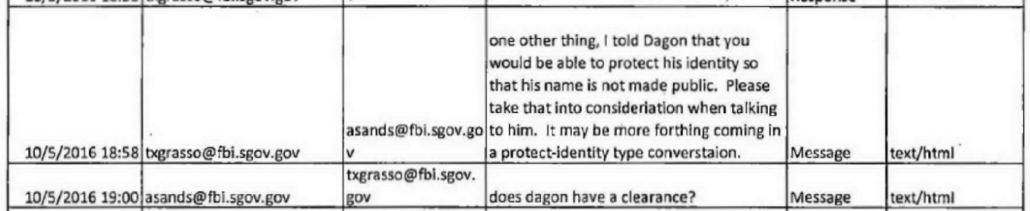

As noted above, Judge Cooper permitted just one email between Joffe and the researchers to come into evidence: a request for feedback Rodney Joffe made of the researches. But he did so based on Durham’s representation that either David Dagon or Manos Antonakakis — both of whom received the email — would testify.

Neither did.

During Sean Berkowitz’ cross-examination of Curtis Heide, one of the agents assigned to investigate the anomaly, Sussmann’s attorney had Heide explain how they knew David Dagon had a role in the research, but nevertheless never bothered to speak to him directly.

AUSA Jonathan Algor used that as an opportunity to ask to introduce not just the email that had been permitted, but also the response, claiming that by highlighting how shoddy the FBI investigation was, Berkowitz was opening the door to accuracy questions.

MR. ALGOR: So, Your Honor, there was a good amount of cross-examination regarding David Dagon.

THE COURT: Yes.

MR. ALGOR: And specifically asking about reaching out to him and also going into that he was the source of the white paper and what types of questions you would ask him and all. I think that this goes right to the red herring email.

THE COURT: I’m sorry, the what email?

MR. ALGOR: The red herring email, which you’ve previously excluded. It was Government Exhibit 124, when you would go through what type of questions. Now that Mr. Berkowitz has asked these, I would ask: What would you have asked having to provide data related to it? You know, Were there drafts of the white paper? Would Agent Heide ask who else he communicated with and what he believed regarding all of that data? And so I think he’s opened the door regarding that email.

Berkowitz noted that neither Sussmann nor Heide knew of the email.

MR. BERKOWITZ: Judge, this is not an email that was authored by Mr. Dagon. My cross-examination went directly to their investigation, who they spoke to, who they didn’t speak to. I asked him, he doesn’t know what Mr. Dagon said to Mr. Sussmann, if anything, and he said he didn’t. And I don’t think that opening the door to these communications where there’s no indication that it went to Mr. Sussmann is appropriate.

Cooper ruled that Algor could not introduce the email response.

That did not open the door to the excluded email about which — about what his and the other researchers’ views on the data or motivations may have been. In any case, the emails reflect — or the email reflects the views of Mr. Joffe, not Mr. Dagon, and those views came a full month and a half before the FBI was in a position to interview Mr. Dagon. They are, therefore, not relevant to Mr. Dagon’s views or motivations in any event.

So you can — you can certainly ask him, as you have in direct, what he would have done differently, what he would have questioned Mr. Dagon about, you know, to establish a materiality argument, but we’re not going to get into what the researchers’ motivations were. Okay?

Minutes later, Algor walked how Heide didn’t know any of the people on the email, and elicited from Heide the opinion that even asking the opinion might suggest people were trying to fabricate the data.

Q. Okay. And it — the “from” is Rodney Joffe. Do you see that?

A. Yes.

Q. And then the “to” is to Manos Antonakakis. Do you see that?

A. Yes.

Q. Do you know who that is?

A. I do not.

Q. And David Dagon, do you see that second name?

A. Yes.

Q. Do you know who David Dagon is?

A. No.

Q. You testified —

A. I’m sorry.

Q. — earlier —

A. I never met David Dagon, but I do know that he was the information that the source came forward and said he was potentially the author of the white paper.

Q. Okay. And that’s from a CHS that your team was contacted by?

A. Yes. Yes.

Q. And then, finally, April Lorenzen. Do you know who April Lorenzen is?

A. I do not.

[snip]

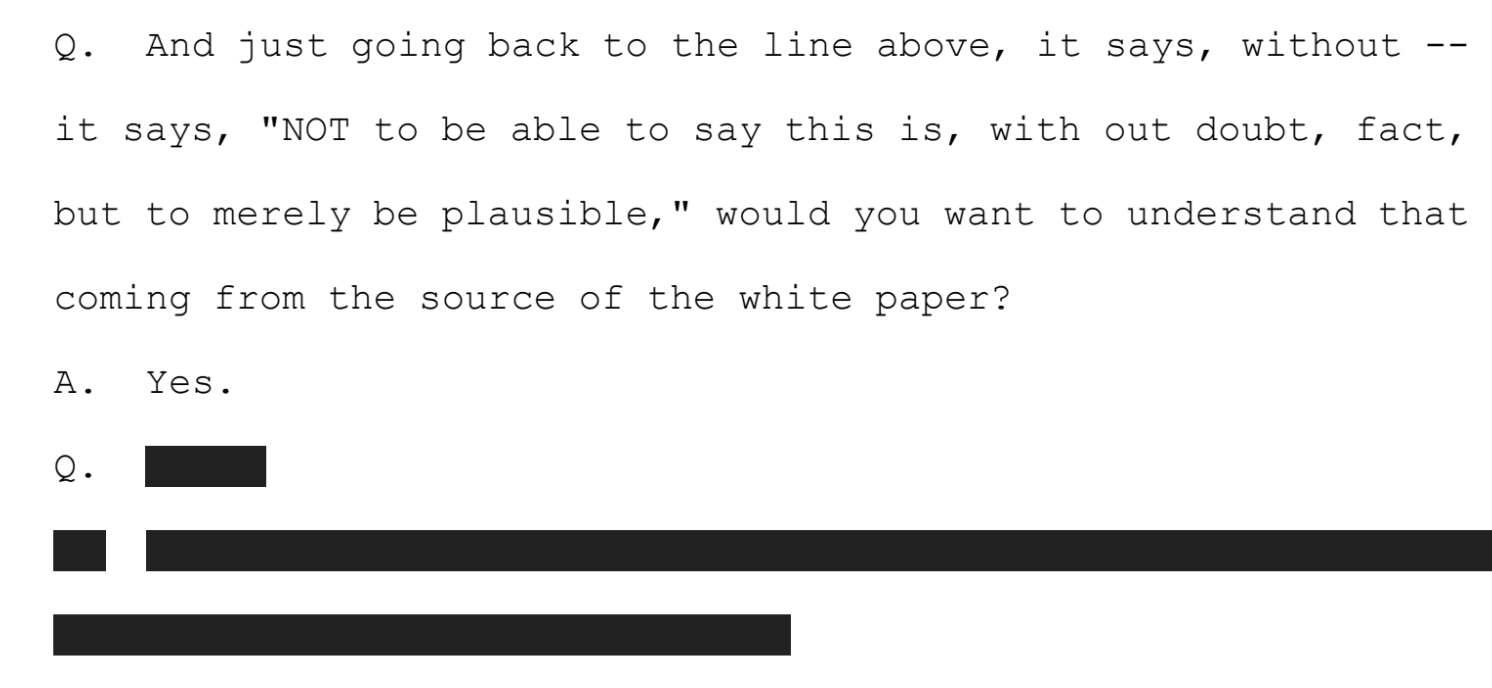

Q. Would you also want to know whether the authors of the white paper were trying to make it out so that it wasn’t — so that it couldn’t be understood if you weren’t a DNS expert?

A. That would be important.

Q. And if you could read that last line, please.

A. It says, “Do NOT spend more than a short while on this (if you spend more than an hour you have failed the assignment). Hopefully less.”

Q. And just going back to the line above, it says, without — it says, “NOT to be able to say this is, with out doubt, fact, but to merely be plausible,” would you want to understand that coming from the source of the white paper?

A. Yes.

The discussion of the bench conference immediately after Heide left the stand (Berkowitz generally refrained from objecting to these shenanigans in front of the jury) is entirely redacted. But as noted below, Judge Cooper ultimately excluded the entire email as hearsay introduced without proper foundation.

6. Hearsay Commentary on an Attorney

In the very same sidebar where Judge Cooper excluded the Heide testimony, he also explicitly prohibited prosecutors from tying a research request that Rodney Joffe had given a colleague, Jared Novick, to an attorney. The research request pertained to Richard Burt and Carter Page (among others) at a time both had established ties to Russia. Novick testified to Joffe’s displeasure with his work abilities and it’s quite clear the two don’t like each other.

MR. BERKOWITZ: So with respect, Judge, to that, it sounds as if outside the norm of what he normally does, that he thought it was likely for a political campaign. I’m not sure that his determination that he thought it was for an attorney is relevant. If they want to put in an attorney-client-privileged document that he saw, I think he can do that. But if he says I understood this was going to an attorney connected to the campaign, that’s hearsay. And it really doesn’t have anything to do with Mr. Sussmann, unless they can tie it up in any way.

THE COURT: Is there — is there any link to the defendant?

MR. ALGOR: Your Honor, just that he understood the tasking was related to opposition research regarding Trump; that he was told by Mr. Joffe — and his understanding was — that it was — it was someone tied to the Clinton campaign. But his understanding overall, full context and understanding, regardless of what Mr. Joffe said, was that this was going to someone tied to the campaign; and that also in receiving the document that had attorney-client privilege, that he understood it to be for an attorney.

THE COURT: How is that not hearsay if Mr. Joffe offered for the purpose of showing that, in fact, it was from —

MR. ALGOR: Because it’s a full understanding. It’s not getting into the actual specific statements that Mr. Joffe told him, but just the full context of what he was tasked to do and who the ultimate receiver was.

THE COURT: Okay.

MR. KEILTY: One second, Your Honor.

THE COURT: You can elicit his understanding that it was for a campaign, that it was unusual, that it may have had some political purpose. But I want you to stay away from any suggestion, which I don’t think has been established, that it was from Mr. Sussmann, including by suggesting it was from an attorney. Okay? [my enphasis]

Once again, minutes after Judge Cooper issued an order — this one ruling that Durham’s team could not elicit any reference to an attorney — Algor nevertheless got a former Joffe associate to do so.

Q. And, again, you — during cross-examination, Mr. Berkowitz asked you a series of questions regarding — regarding your work for Mr. Joffe on this project?

A. Uh-huh.

Q. And without getting into any specific conversations, based on the totality of your work, who was the intended audience for the project?

A. It was to go to an attorney with ties.

MR. BERKOWITZ: Objection, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Sustained.

That was the first time Berkowitz started getting really insistent about the pattern of Durham’s prosecutors completely ignoring explicit prohibitions from Cooper.

MR. BERKOWITZ: And — and just briefly, Your Honor, I don’t know when is an appropriate time to — to raise this. I want to express what — and I am not a — a hotheaded person —

THE COURT: You’re not a what?

MR. BERKOWITZ: I’m not a hotheaded person, but I have deep concern over the last line of questioning with the witness eliciting something that I think was clearly prohibited. And it’s consistent, in our view, with the line of questioning relative to Mr. Elias, [sic] relative to them reading the tweet that had been excluded. And, again, I know you don’t apportion bad faith, and I’m not asking you to do that at this point, but I just — I’m — I’m really concerned about the number of those issues that have come in and the prejudice to Mr. Sussmann. And I don’t know how best to deal with it, but I want to raise that to your attention.

Judge Cooper finally warns Durham to follow his orders

The Novick questioning finally stirred Cooper to try to do something about prosecutors flouting his orders. The first thing the next morning, he issued a both-sides warning about adhering to his rulings.

THE COURT: Okay. Good morning, everybody. All right. I just want to return briefly to the discussion we had at the end of the day yesterday.

You know, we’ve been here for two weeks. I have tried my best to let you folks try your cases as you see fit without undue intervention from the Court, as is my usual practice. But I obviously have set some evidentiary guardrails in the case that I expect both sides to follow, and I think you’ve done that for the most part.

Yesterday, however, I thought it was pretty clear — that I was pretty clear that in Mr. Novick’s testimony the government was not to suggest a link between the defendant and — on the one hand, and Mr. Joffe and the researchers’ data collection efforts on the other hand, or their views about the data. I didn’t think there was an evidentiary foundation for that.

I thought that the jury would only be able to speculate about any such connection, and I thought that any knowledge Mr. Novick had about that was necessarily hearsay from Mr. Joffe, who obviously is not here to testify. And I thought, at least, the final question in the redirect that was asked yesterday, nevertheless, attempted to establish such a link.

You know, I know that questions get asked rhetorically or argumentatively that are likely to draw an objection, and I will give lawyers some slack on that, but I expect both sides to comply with my evidentiary rulings.

There’s a lot of evidence in this case. There’s a lot for the jury to digest. They will have plenty of validly admitted evidence to pore over, and from here on out, including in arguments, I expect both sides to comply with both the letter and the spirit of the Court’s evidentiary rulings. So let’s keep it clean from here, okay?

MR. KEILTY: Yes, Your Honor.

Berkowitz used that exchange to request that Cooper exclude the entirety of the email that Algor used to invite Heide to suggest the data had been fabricated as the only way to limit the damage from prosecutors breaking Cooper’s rules.

MR. BERKOWITZ: Thank you very much for that, Your Honor. I have one other request related to it. And I don’t mean to go to the well, but there was an additional line of questioning yesterday related to Government Exhibit 132 with Agent Heide. I’m happy to provide a copy of it, if you would like.

THE COURT: Just remind me what it is.

MR. BERKOWITZ: It’s the document they sought to admit between Rodney Joffe, David Dagon, and Manos Antonakakis, “Is this a plausible explanation?”

THE COURT: Yes, I know that one. Actually, pass it up.

MR. BERKOWITZ: Your Honor, I went back and read the basis for your admitting the document, which was that it was not hearsay because there was a statement, “can you review,” and a question, “is this a plausible explanation?” I think we all contemplated at the time that both Mr. Dagon and Mr. Antonakakis were on the witness list and might testify.

You did allow it in. We didn’t object on the basis that you had previously ruled on it.

The manner in which it was used with the witness, I think, didn’t comply with the spirit of the Court’s ruling. There were questions asked related to “if you had spoken with Mr. Dagon, and you were aware of this communication” words to the effect of “would that have been concerning?”

And the witness — and I’m not suggesting that it was elicited intentionally, but the witness said “it would concern me because it appears as if it’s fabricated.”

Berkowitz noted that (like the Clinton tweet before it, though Berkowitz didn’t make the connection) that exchange got reported in the press.

That’s been reported in the press, even though you struck it from the record at our request.

Our remedy request, Your Honor, in light of that, and in light of the lack of probative value of that document with no connection to Mr. Sussmann, would be to strike the question and answering related to that document, to strike that document from the record, and not allow the prosecution team to use it with any defense witnesses, as well as not to use it in argument because it would have been stricken from the record.

We think the probative value of that document at this stage is minimal, and I expect that if it is published to the jury and used in any way, the jurors will associate it with the fabrication comment. And you worked real hard — and we have all worked really hard — to keep out the accuracy of the data. And the prejudicial nature of the document and the testimony associated with it is something that we think, while it can’t be remedied, and the bell can never be unrung, they should not be reminded and put before them. [my emphasis]

After having just been scolded, DeFilippis nevertheless made a bid to keep the document that might trigger the improperly elicited comment in as evidence.

Michael Keilty — the closest thing to a grown-up on this team — then tried to explain away Algor’s flouting of the rules with Novick.

MR. KEILTY: One last thing, Your Honor, just with respect to the final question to Mr. Novick yesterday. I think Your Honor’s aware that the government obviously did not intend for that — to elicit that answer. Instead, it intended to elicit an answer regarding Mr. Novick’s thoughts about whether this was involved with a political entity or political campaign. We didn’t have the opportunity or the benefit of conferring with Mr. Novick prior to Your Honor’s ruling. So we apologize for that, but we just wanted to put on the record some of the reasons why.

THE COURT: Well, you could have asked, “Without telling me who it came from, what was your understanding of the general nature of the source?” Right?

7. Hearsay on Top of Hearsay about Joffe’s Joke about a Job

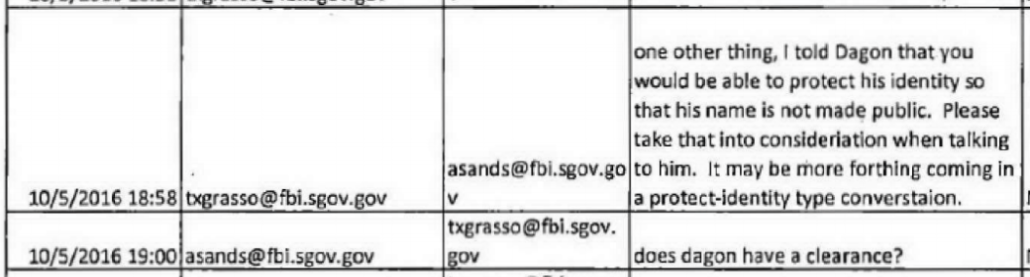

But the Durham team’s defiance of Cooper didn’t stop there. While Cooper had permitted (with the proper foundation) a Joffe email that elicited feedback, Cooper had excluded an email — sent to someone never identified as a witness in this case — in which Joffe had joked about working in cybersecurity under a Clinton Administration. Nevertheless, as part of a long exchange with retired FBI Agent Tom Grasso in which DeFilippis asked Grasso materiality questions about stuff he heard about but had no firsthand knowledge of — each time presented as fact rather than as a conspiracy that Durham had explicitly been prohibited from presenting because they hadn’t charged it — Durham’s lead prosecutor raised the allegation he had been prohibited from raising.

Q. So when he came to you or at any time after that, did Mr. Joffe disclose to you whether he was working on this with representatives of the — of a political campaign?

A. He did not, no.

Q. And do you think you’d remember if he had told you at the time, you know, “I’m doing this, working with some folks who are working with the political campaign”?

A. I would think I would remember that, yes.

Q. So Mr. Joffe didn’t tell you — have you heard of a firm called Fusion GPS?

A. I have heard of Fusion GPS, yes, sir.

Q. Okay. And are you generally aware that they had — without getting into any specific work you did, are you generally aware that they had done some work for the Clinton Campaign at the time?

A. Yes, I —

Q. Okay.

A. Yes, I am aware of that, yes.

Q. So Mr. Joffe didn’t say he was working with Fusion GPS on this project?

A. Not that I recall, no.

Q. And Mr. Joffe never told you that, you know, this project had arisen in the context of opposition research that the Clinton Campaign was working on?

A. I do not recall that coming up, no.

Q. If Mr. Joffe had come to you and said, “I’m working with some investigators and some lawyers who are working for the Clinton Campaign, and, you know, that’s part of what I’m doing here with this information, can you please keep my name out of this,” would you have viewed that differently than you viewed the information as you got it?

[snip]

Q. Okay. And in the 2016 election period, you and Mr. Joffe, I imagine, never discussed politics or anything like that?

A. I don’t recall political discussions with him, no.

Q. Okay. And did you — so you certainly didn’t know that he was working with folks affiliated with a particular political party or campaign on what he brought to you, right?

A. I have no recollection of that.

Q. And any recollection of hearing or learning that he was expecting any kind of position in a future political administration?

A. I do not have a recollection of that other than — let me rephrase that. I have a recollection of that being reported in the media, but I don’t have a —

MR. BERKOWITZ: Objection, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Sustained. [my emphasis]

When Berkowitz raised this exchange at the end of the day, Judge Cooper noted that the several meetings they had with Grasso were ample basis for DeFilippis to understand that Grasso had no knowledge of those matters (or, for that matter, the topics covered by that entire line of questioning).

MR. BERKOWITZ: Judge, I regret that I’m going back to this same issue that we started the day with where you admonished counsel to be careful of the guardrails related to evidentiary rulings. We had another situation n today that I think ran afoul of your comments. There was an email that was the subject of a motion related to Mr. Joffe communicating about a potential job. And in the cross-examination of Agent Grasso there was a question about, “He certainly didn’t know he was working with folks affiliated with a particular political party or campaign when he brought that to you. Right?”

Answer: “I have no recollection of that.” I didn’t object.

And then he followed up with: “And any recollection of hearing or learning that he was expecting any kind of position in a future political administration, knowing that there was nothing in the 3500 materials related to that and knowing an objection that was sustained could elicit a belief that he would do that?”

The witness answered, “I do not have a recollection of that other than — let me rephrase that. I have a recollection of that being reported in the media.”

I objected. Your Honor, they had met with this witness four times. They had pretried him twice. There was nothing in the 3500 material to suggest that he had any belief of that or any recollection or any connection.

And it’s another instance in a litany of instances that’s suggesting to the jury topics and issues that were the subject of your ruling. And I, you know, particularly with the potential testimony of Mr. Sussmann coming up, I don’t know what else to say or to do, and we’ll consider filing a motion. But I wanted to raise the issue, and I take no joy in continuing to do this. But I cannot stand by while it continues to go on.

DeFilippis at first tried to excuse blowing off Cooper’s ruling by saying that the rules for cross-examination are different. But not if the witness was originally a witness for the prosecution.

THE COURT: Counsel?

MR. DeFILIPPIS: Yes, Your Honor. I guess we’re glad that Mr. Berkowitz raised it in the sense that, you know, typically the rules for cross-examination are different from evidence presented in a case in chief. And if there is a good-faith basis to ask — inquire as to knowledge of a matter, Your Honor, the government didn’t phrase the question tethered to any email or refer to any hearsay.

It was just inquiring as to knowledge and then inquiring as to whether that fact would be relevant to what it is that Mr. Grasso’s interactions with Mr. Joffe were.

So if, again if the Court wants —-

THE COURT: Counsel, I don’t disagree with that, but you got to have a good faith basis for asking the question. Right? And if you prepped this guy and he’s never said anything about it, then there’s no good-faith basis. Okay? Him reading it in The New York Times or whatever is not a good-faith basis.

Then DeFilippis claimed that the question — which came after two earlier ones in which he asked Grasso questions about things he had “heard of” — was not deliberately intended to elicit such a response.

MR. DeFILIPPIS: Yeah, and to be clear, Your Honor, the portion where he said he read in the — we didn’t know that, and we wouldn’t have intentionally elicited something from a press account. So we will certainly be careful.

THE COURT: He was the defense’s witness here, but he was on your witness list. You should have known. If there was a basis to ask that question, you should have known what it was.

MR. DeFILIPPIS: Yeah. Understood, Your Honor.

Only after this exchange on prosecutors using someone who had originally been a government witness to invite speculation did Cooper exclude the entire email discussion involving Heide.

THE COURT: In that vein, let’s go back to GX-132 the admission of the email did not sit well with me yesterday, and it still does not sit well with me.

The Court ruled that the document was [sic] hearsay originally because it contained a question and a request, as opposed to an assertion. But the Court made clear in its order that, in order to be admitted, it would still need a proper foundation. The witness through which the document ultimately was admitted, albeit not without an objection from the defense, was Mr. Heide, who, as far as I could tell, had no personal knowledge whatsoever of the email. He didn’t know Mr. Joffe. He didn’t know the researchers who received it. He obviously was not a party to the email. So frankly, I don’t see how he could testify to that email in his personal knowledge as required by Rule 602.

So for that reason, I don’t think it was properly admitted through that witness. As I said yesterday, we had expected at least two of the researchers to testify based on who was on the government’s list. And I think it would have been properly admissible through those people to explain how the data came into being as the Court ruled prior to trial. So I am going to exclude that email as well as any testimony by Mr. Heide describing his interpretation or views or thoughts on the email. Okay?

Conspiracy theory

This repeated defiance of Judge Cooper was treated as one after another evidentiary issue, usually prosecutors sneaking in hearsay with no basis. Ultimately, however, it was about a more basic ruling Judge Cooper had made, that this trial would not be about a conspiracy theory that Durham wanted to criminalize without charging.

As Berkowitz observed in his close,

This case is not about a giant political conspiracy theory. It’s about a short meeting.

[snip]

So the people who were part of this large political conspiracy theory are the people at HFA, Rodney Joffe, and Fusion GPS. They’re the people that are supposedly involved in this conspiracy.

There will be a lot said about this trial, no matter the verdict. But the serial defiance of the Durham prosecutors was a successful attempt to do something else that Judge Cooper had prohibited: to criminalize, under a conspiracy theory, perfectly legal behavior.

OTHER SUSSMANN TRIAL COVERAGE

Scene-Setter for the Sussmann Trial, Part One: The Elements of the Offense

Scene-Setter for the Sussmann Trial, Part Two: The Witnesses

The Founding Fantasy of Durham’s Prosecution of Michael Sussmann: Hillary’s Successful October Surprise

With a Much-Anticipated Fusion GPS Witness, Andrew DeFilippis Bangs the Table

John Durham’s Lies with Metadata

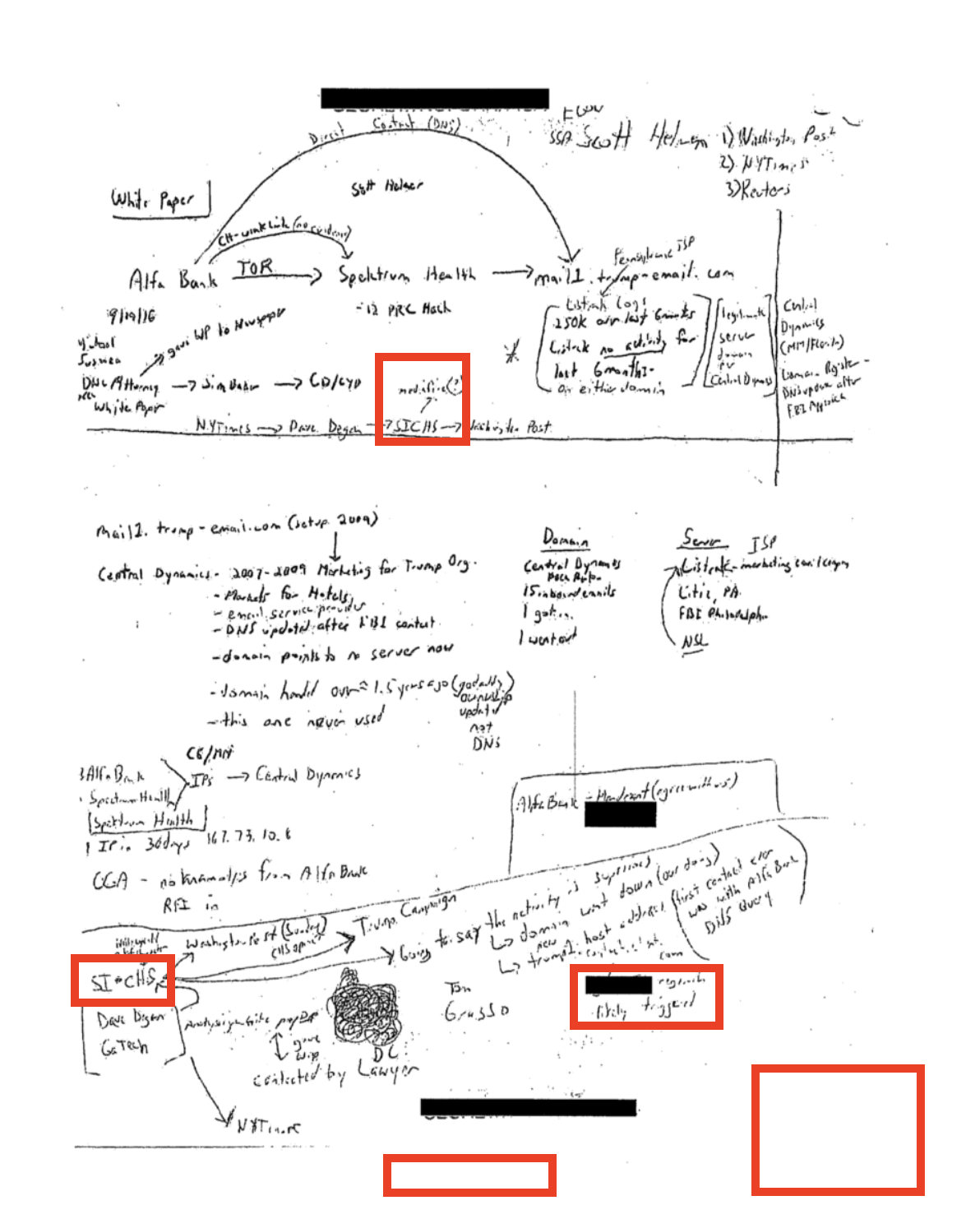

emptywheel’s Continuing Obsession with Sticky Notes, Michael Sussmann Trial Edition

Brittain Shaw’s Privileged Attempt to Misrepresent Eric Lichtblau’s Privilege

The Methodology of Andrew DeFilippis’ Elaborate Plot to Break Judge Cooper’s Rules

Jim Baker’s Tweet and the Recidivist Foreign Influence Cheater

That Clinton Tweet Could Lead To a Mistrial (or Reversal on Appeal)

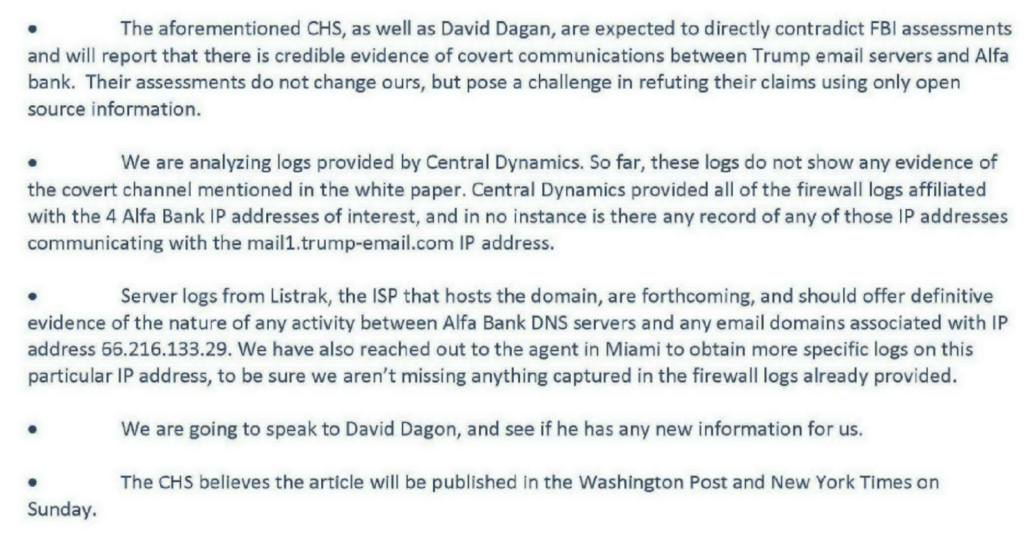

John Durham Is Prosecuting Michael Sussmann for Sharing a Tip on Now-Sanctioned Alfa Bank

Apprehension and Dread with Bates Stamps: The Case of Jim Baker’s Missing Jencks Production

Technical Exhibits, Michael Sussmann Trial

Jim Baker’s “Doctored” Memory Forgot the Meeting He Had Immediately After His Michael Sussmann Meeting

The FBI Believed Michael Sussmann Was Working for the DNC … Until Andrew DeFilippis Coached Them to Believe Otherwise

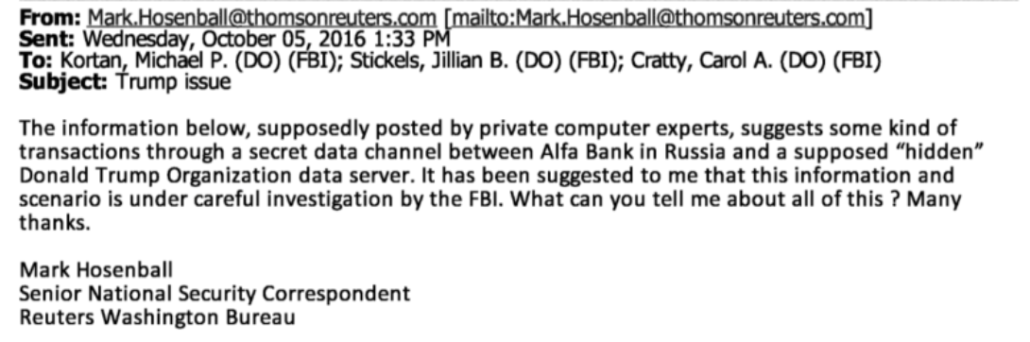

The Visibility of FBI’s Close Hold: John Durham Will Blame Michael Sussmann that FBI Told Alfa Bank They Were Investigating

The Staples Receipt and FBI’s Description of Michael Sussmann Sharing a Tip from Hillary

“and” / “or” : How Judge Cooper Rewrote the Michael Sussmann Indictment