Problems With The Standard Story Of The Revolutionary War And The Constitution

The standard story of the origin of our nation tells us that the Declaration of INdependence asserts that all men are created equal and naturally endowed with certain rights including the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that the Revolutionary War was fought to uphold these principles; and that the principles are instantiated in the Constitution. We didn’t always live up to those principles but we’ve always worked towards them, and we get closer all the time. P. 9 et seq. In the first post in this series, we saw that the Declaration doesn’t fit well with the standard story. What about the Revolutionary War and the Constitution?

The Revolutionary War

Roosevelt doesn’t think there was a single cause for the War.

Different people sought independence for different reasons, and likely they sometimes said what they thought would advance their cause rather than what they truly believed. History requires interpretation, and a claim to possession of the one singular truth is a hallmark of ideology. P. 55.

The Declaration explains the decision of the Colonists to throw off English rule. It claims that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. The Declaration complains that the King cut off trade between the Colonies and the rest of the world. It claims that the King ignores the laws and even the courts of the Colonists. The King attacks the Colonies directly, keeps a standing army in the Colonies, and quarters troops on the population. The King imposes taxes on the Colonies even though they are not represented in Parliament. The King stirs up the “merciless savages” to attack and murder the Colonists. The only reference to slavery is oblique: the King “… has excited domestic insurrections amongst us….”

No doubt one or more of these claims were a factor for some of the Colonists. The principle of consent itself may have motivated some of them. The listed claims may have motivated others. Perhaps some were motivated by a desire to bring about equality or at least to end slavery (Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin, for example.) Roosevelt points out that protecting slavery may have brought others into the war:

There isn’t much evidence supporting the idea that slavery was an issue. Of course just as people say things they don’t believe to advance their cause, others may keep quiet about their actual reasons if they would hurt the cause. There was little to be gained by saying we’re rebelling because we want to enslave people. Roosevelt suggests that

… for some of the Patriots, a desire to preserve slavery was one reason—and maybe a strong one—to declare independence[.] On its face, this is pretty plausible. Just as it seems unlikely that northern Patriots had slavery at the front of their minds, it is unlikely the southern ones didn’t have it at least at the back of theirs. P. 53.

In any event it’s hard to argue that the War was fought over the principle of equality for anyone except white men and especially white men with property. A telling detail: the British offered slaves freedom if they fought for the King. After the War the Colonists demanded the return to slavery of those people. The British refused.

Nor was the Revolution fought to advance a broad principle of equality. Roosevelt says that the statement that all men are created equal is a reference to the fictional state of nature assumed to exist in the beginning. The broader concept of equality would have to wait for the French Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789. It asserts that “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” This is a statement about real people living in real societies, not imaginary savages in the wild.

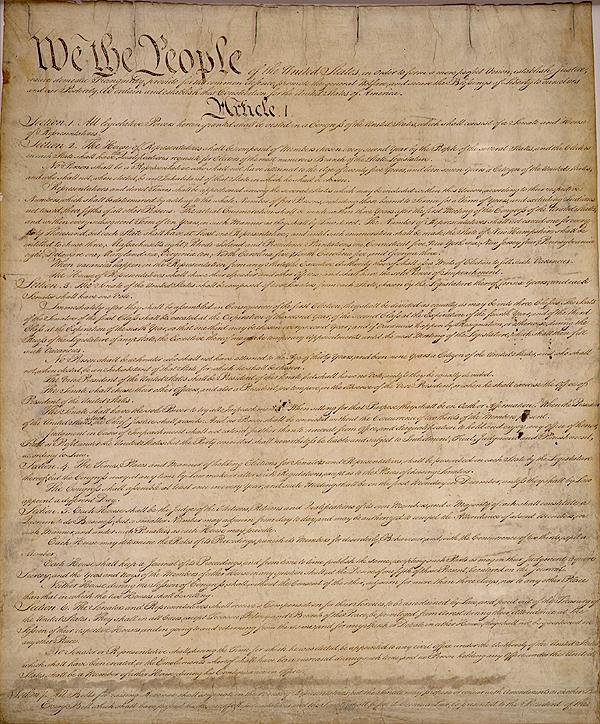

The Constitution

The Constitution was necessary because the Articles of Confederation failed to create a strong enough central government. The states were fighting among themselves, refusing to adhere to treaties, imposing trade restrictions and refusing to pay the debts incurred in the Revolutionary War. The preamble states the reasons for adoption of the Constitution, starting with “to produce a more perfect union”, and ending with “to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” Roosevelt says that the chief goal of the Constitution was unity, with liberty at the bottom of the list.

If the Constitution were actually about individual human rights, it would include provisions that protected the rights of individuals. It doesn’t. The Founders Constitution restricts the Federal Government’s right to intrude on the specific rights in the Bill of Rights, but the states were free to intrude as much as their own constitutions allowed. It took the 14th Amendment to change that, and to make the Federal Government the guarantor of individual rights against itself and against the states.

As to slavery, there are three provisions that directly or indirectly support its continuation: the Three-Fifths Clause, a provision barring the Federal Government from ending the international slave trade until 1808, and the Fugitive Slave Clause. Each of these cemented the power of the slave states.

The Three-Fifths Clause redressed the population imbalance between the slave states and the rest, allowing slaves to be counted at ⅗ of a person for purposes of calculating the number of Representatives allocated to each state. It worked with the provision giving each state two senators to insure a balance in the legislature between slave and free states. In addition it gave the slave states an edge in the Electoral College with respect to population. Thomas Jefferson would have lost the election of 1800 to John Adams without the Three-Fifths Clause. Ten of the first 12 presidents were slavers. P. 76.

The prohibition on ending the slave trade before 1808 enabled slavers to rebuild their holdings by importation after losses in the Revolutionary War. The British offered freedom to any slave who fought for the King, and thousands of slaves accepted this offer. Others escaped their bonds. The Colonists demanded return of these escapees, but the British refused. The outcome is that slave population rose from 697,497 in the first census of 1790 to 1,191,362 in the 1810 census.

The Fugitive Slave Clause says that slaves who escaped to a free state did not gain their freedom, and that the free state was required to return them to their enslavers. This was a big win for the slavers. Under the Articles, each state determined how it would treat slaves in their territory; in fact that rule remained in effect as to slaves brought to free states by their masters. The Constitution stripped the States of their right to decide the question of slavery as to escapees, which today we would call a violation of States Rights.

As South Carolina delegate Charles Cotesworth Pinckney boasted upon his return from the Constitutional Convention, “We have obtained a right to recover our slaves in whatever part of America they may take refuge, which is a right we had not before.” P. 79.

Discussion

1. The standard story has a central place in our understanding of ourselves as Americans, regardless of other political views. Other nations have national stories, but it seems like we put a lot of emphasis on this story and the two documents, more than citizens of other countries do.

2. One consistent element of our self-image as Americans is that we consent to our government. In prior posts I’ve discussed the theoretical idea of the social contract. That’s not what I’m talking about. We believe that government only works if people consent to it.

Apparently that belief is not shared by a substantial of Republicans today. In this they are like the secessionist Confederates, as Heather Cox Richardson shows.

“We do not agree with the authors of the Declaration of Independence, that governments ‘derive their just powers from the consent of the governed,’” enslaver George Fitzhugh of Virginia wrote in 1857. “All governments must originate in force, and be continued by force.” There were 18,000 people in his county and only 1,200 could vote, he said, “But we twelve hundred . . . never asked and never intend to ask the consent of the sixteen thousand eight hundred whom we govern.”

3. Regardless of what Jefferson meant with the phrase all men are created equal, today we flatly mean that we’re all born equal, we’re all entitled to equal rights, and that one function of government is to guarantee that equality.

Apparently that belief is not shared by a substantial number of Republicans.