On Ginni Thomas’ Obstruction Exposure and Clarence’s Former Clerk, Carl Nichols

In a motions hearing for January 6 assault defendant Garret Miller on November 22, former Clarence Thomas clerk Carl Nichols asked the appellate prosecutor for the January 6 investigation, James Pearce, whether someone asking Mike Pence to invalidate the vote count could be charged with the obstruction statute, 18 USC 1512(c)(2), that Miller was challenging. Pearce replied that the person in question would have to know that such a request of the Vice President was improper.

At a hearing on Monday for defendant Garret Miller of Richardson, Texas, Nichols made the first move toward a Trump analogy by asking a prosecutor whether the obstruction statute could have been violated by someone who simply “called Vice President Pence to seek to have him adjudge the certification in a particular way.” The judge also asked the prosecutor to assume the person trying to persuade Pence had the “appropriate mens rea,” or guilty mind, to be responsible for a crime.

Nichols made no specific mention of Trump, who appointed him to the bench, but the then-president was publicly and privately pressuring Pence in the days before the fateful Jan. 6 tally to decline to certify Joe Biden’s victory. Trump also enlisted other allies, including attorney John Eastman, to lean on Pence.

An attorney with the Justice Department Criminal Division, James Pearce, initially seemed to dismiss the idea that merely lobbying Pence to refuse to recognize the electoral result would amount to the crime of obstructing or attempting to obstruct an official proceeding.

“I don’t see how that gets you that,” Pearce told the judge.

However, Pearce quickly added that it might well be a crime if the person reaching out to Pence knew the vice president had an obligation under the Constitution to recognize the result.

“If that person does that knowing it is not an available argument [and is] asking the vice president to do something the individual knows is wrongful … one of the definitions of ‘corruptly’ is trying to get someone to violate a legal duty,” Pearce said.

At the time (as Josh Gerstein wrote up in his piece), we knew that former Clarence Thomas clerk John Eastman had pressured Pence to throw out legal votes.

But we’ve since learned far more details about Eastman’s actions, including his admissions to Pence’s counsel, Greg Jacob, that there was no way SCOTUS would uphold the claim. In fact, those admissions were cited in Judge David Carter’s opinion finding that Eastman himself likely obstructed the vote count by pressuring Pence to reject the valid votes, because he knew that not even Clarence Thomas would buy this argument.

Ultimately, Dr. Eastman conceded that his argument was contrary to consistent historical practice,37 would likely be unanimously rejected by the Supreme Court,38 and violated the Electoral Count Act on four separate grounds.39

[snip]

Dr. Eastman himself repeatedly recognized that his plan had no legal support. In his discussion with the Vice President’s counsel, Dr. Eastman “acknowledged” the “100 percent consistent historical practice since the time of the Founding” that the Vice President did not have the authority to act as the memo proposed.254 More importantly, Dr. Eastman admitted more than once that “his proposal violate[d] several provisions of statutory law,”255 including explicitly characterizing the plan as “one more relatively minor violation” of the Electoral Count Act.256 In addition, on January 5, Dr. Eastman conceded that the Supreme Court would unanimously reject his plan for the Vice President to reject electoral votes.257 Later that day, Dr. Eastman admitted that his “more palatable” idea to have the Vice President delay, rather than reject counting electors, rested on “the same basic legal theory” that he knew would not survive judicial scrutiny.258

We’ve also learned more details about Ginni Thomas’ role in pressuring Mark Meadows to champion an attempt to steal the election, including — after a gap in the texts produced to the January 6 Committee — attacking Pence.

The committee received one additional message sent by Thomas to Meadows, on Jan. 10, four days after the “Stop the Steal” rally Thomas said she attended and the deadly attack on the Capitol.

In that message, Thomas expresses support for Meadows and Trump — and directed anger at Vice President Mike Pence, who had refused Trump’s wishes to block the congressional certification of Biden’s electoral college victory.

“We are living through what feels like the end of America,” Thomas wrote to Meadows. “Most of us are disgusted with the VP and are in listening mode to see where to fight with our teams. Those who attacked the Capitol are not representative of our great teams of patriots for DJT!!”

“Amazing times,” she added. “The end of Liberty.”

Ginni Thomas famously remains close with a network of Clarence’s former clerks, so much so she apologized to a listserv of former Justice Thomas clerks for her antics after the insurrection.

Any former Thomas clerk on that listserv would likely understand how exposed in efforts to overturn the vote certification Ginni was.

As I said, little of that was known, publicly, when former Justice Thomas clerk Carl Nichols asked whether someone who pressured Pence could be exposed for obstruction. We didn’t even, yet, know all these details when Judge Nichols ruled in Miller’s case on March 7, alone thus far of all the DC District judges, against DOJ’s application of that obstruction statute. While we had just learned some of the details about Jacobs’ interactions with former Thomas clerk John Eastman, we did not yet know how centrally involved Ginni was — frankly, we still don’t know, especially since the texts Mark Meadows turned over to the January 6 Committee have a gap during the days when Eastman was most aggressively pressuring Pence.

DOJ may know but if it does it’s not telling.

But now we know more of those details and now we know that Judge Carter found that Eastman and Trump likely did obstruct the vote certification. All those details, combined with Nichols’ treatment of the Miller decision as one that might affect others, up to and including Ginni Thomas and John Eastman and Trump, sure makes it look a lot more suspect that a former Clarence Thomas clerk would write such an outlier decision.

Which brings us to the tactics of this DOJ motion to reconsider filed yesterday in the Miller case. It makes two legal arguments and one logical one.

As I laid out here, Nichols ruled that the vote certification was an official proceeding, but that the statute in question only applied to obstruction achieved via the destruction of documents. He also held that there was sufficient uncertainty about what the statute means that the rule of lenity — basically the legal equivalent of “tie goes to the runner” — would apply.

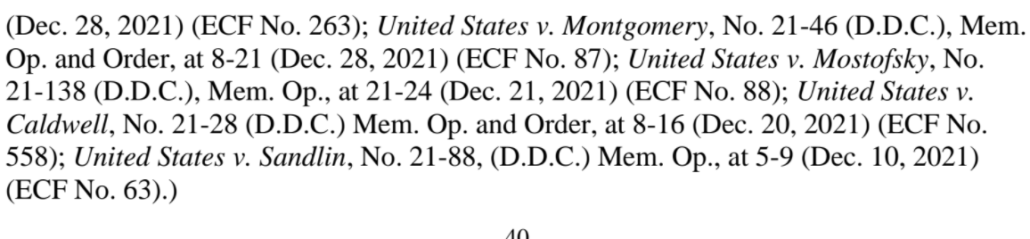

DOJ challenged Nichols’ claim that there was enough uncertainty for the rule of lenity to apply. After all, the shade-filled motion suggested, thirteen of Nichols’ colleagues have found little such uncertainty.

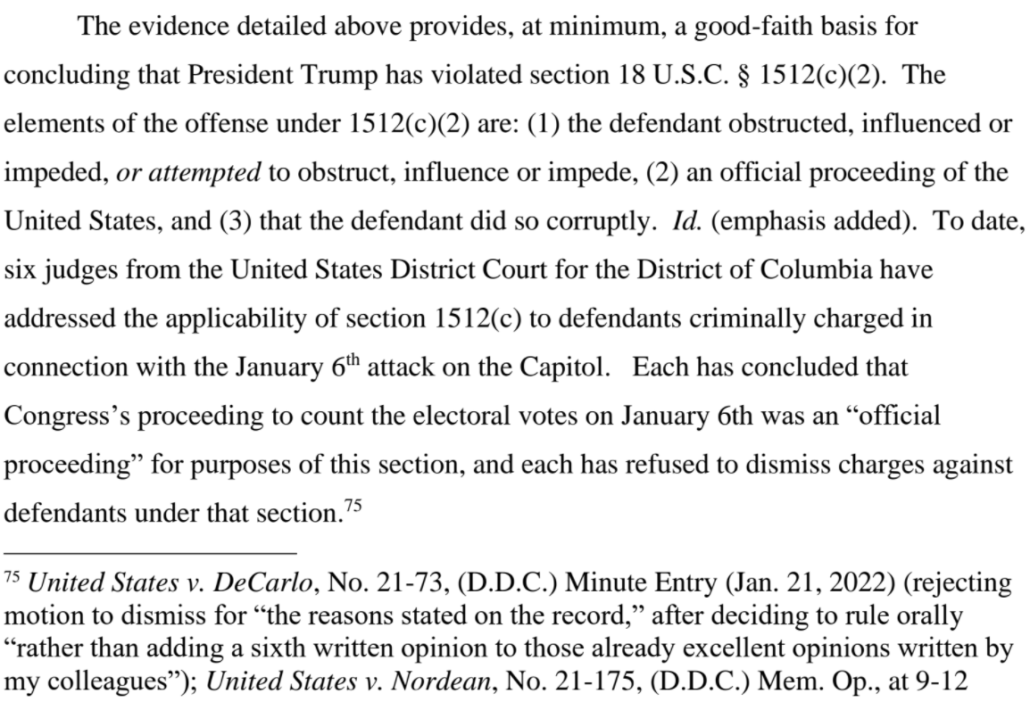

First, the Court erred by applying the rule of lenity. Rejecting an interpretation of Section 1512(c)(2)’s scope that every other member of this Court to have considered the issue and every reported case to have considered the issue (to the government’s knowledge) has adopted, the Court found “serious ambiguity” in the statute. Mem. Op. at 28. The rule of lenity applies “‘only if, after seizing everything from which aid can be derived,’” the statute contains “a ‘grievous ambiguity or uncertainty,’” and the Court “‘can make no more than a guess as to what Congress intended.’” Ocasio v. United States, 578 U.S. 282, 295 n.8 (2016) (quoting Muscarello v. United States, 524 U.S. 125, 138-39 (1998)) (emphasis added); see also Mem. Op. at 9 (citing “‘grievous’ ambiguity” standard). Interpreting Section 1512(c)(2) consistently with its plain language to reach any conduct that “obstructs, influences, or impedes” a qualifying proceeding does not give rise to “serious” or “grievous” ambiguity.

[snip]

First, the Court erred by applying the rule of lenity to Section 1512(c)(2) because, as many other judges have concluded after examining the statute’s text, structure, and history, there is no genuine—let alone “grievous” or “serious”—ambiguity.

[snip]

Confirming the absence of ambiguity—serious, grievous, or otherwise—is that despite Section 1512(c)(2)’s nearly 20-year existence, no other judge has found ambiguity in Section 1512(c)(2), including eight judges on this Court considering the same law and materially identical facts. See supra at 5-6.

[snip]

Before this Court’s decision to the contrary, every reported case to have considered the scope of Section 1512(c)(2), see Gov’t Supp. Br., ECF 74, at 7-9, 1 and every judge on this Court to have considered the issue in cases arising out of the events at the Capitol on January 6, 2021, see supra at 5-6, concluded that Section 1512(c)(2) “prohibits obstruction by means other than document destruction.” Sandlin, 2021 WL 5865006, at *5. [my emphasis; note, not all of the 13 challenges to 1512(c)(2) that were rejected made a rule of lenity argument, which is why AUSA Pearce cited eight judges]

Among the other things that this argument will force Nichols to do if he wants to sustain his decision, on top of doubling down on being the extreme outlier on this decision, is to engage with all his colleagues’ opinions rather than (as he did in his original opinion) just with Judge Randolph Moss’.

The government then argued that by deciding that 1512(c)(2) applied to the vote certification but only regarding tampering with documents, Nichols was not actually ruling against DOJ, because he can only dismiss the charge at this stage if the defendant, Miller, doesn’t know what he is charged with, not if the evidence wouldn’t support such a charge.

Although Miller has styled his challenge to Section 1512(c)(2)’s scope as an attack on the indictment’s validity, the scope of the conduct covered under Section 1512(c)(2) is distinct from whether Count Three adequately states a violation of Section 1512(c)(2).6 Here, Count Three of the indictment puts Miller on notice as to the charges against which he must defend himself, while also encompassing both the broader theory that a defendant violates Section 1512(c)(2) through any corrupt conduct that “obstructs, impedes, or influences” an official proceeding and the narrower theory that a defendant must “have taken some action with respect to a document,” Mem. Op. at 28, in order to violate Section 1512(c)(2). The Court’s conclusion that only the narrower theory is a viable basis for conviction should not result in dismissal of Count Three in full; instead, the Court would properly enforce that limitation by permitting conviction on that basis alone.

The government argues that that means, given Nichols’ ruling, the government must be given the opportunity to prove that Miller’s actions were an attempt to spoil the actual vote certifications that had to be rushed out of the Chambers as mobsters descended.

Even assuming the Court’s interpretation of Section 1512(c)(2) were correct, and that the government therefore must prove “Miller took some action with respect to a document, record, or other object in order to corruptly obstruct, impede[,] or influence Congress’s certification of the electoral vote,” Mem. Op. at 29, the Court cannot determine whether Miller’s conduct meets that test until after a trial, at which the government is not limited to the specific allegations in the indictment. 7 And at trial, the government could prove that the Certification proceeding “operates through a deliberate and legally prescribed assessment of ballots, lists, certificates, and, potentially, written objections.” ECF 74, at 41. For example, evidence would show Congress had before it boxes carried into the House chamber at the beginning of the Joint Session that contained “certificates of votes from the electors of all 50 states plus the District of Columbia.” Reffitt, supra, Trial Tr. at 1064 (Mar. 4, 2022) (testimony of the general counsel to the Secretary of the United States Senate) (attached as Exhibit B).

Those are the two legal arguments the government has invited Nichols to reconsider.

But along the way of making those arguments, DOJ pointed out the absurd result dictated by Nichols’ opinion: That Guy Reffitt’s physical threats against members of Congress or the threat Miller is accused of making against Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez would not be obstruction, because neither man touched any documents.

Any such distinction between these forms of obstruction produces the absurd result that a defendant who attempts to destroy a document being used or considered by a tribunal violates Section 1512(c) but a defendant who threatens to use force against the officers conducting that proceeding escapes criminal liability under the statute.

[snip]

Finally, an interpretation of Section 1512(c)(2) that imposes criminal liability only when an individual takes direct action “with respect to a document, record, or other object” to obstruct a qualifying proceeding leads to absurd results. See United States v. X-Citement Video, Inc., 513 U.S. 64, 69 (1994) (rejecting interpretation of a criminal statute that would “produce results that were not merely odd, but positively absurd”). That interpretation would appear, for example, not to encompass an individual who seeks to “obstruct[], influence[], or impede[]” a congressional proceeding by explicitly stating that he intends to stop the legislators from performing their constitutional and statutory duties to certify Electoral College vote results by “drag[ging] lawmakers out of the Capitol by their heels with their heads hitting every step,” United States v. Reffitt, 21-cr-32 (DLF), Trial Tr. 1502, carrying a gun onto Capitol grounds, id. at 1499, and then leading a “mob and encourag[ing] it to charge toward federal officers, pushing them aside to break into the Capitol,” id. at 1501-02, unless he also picked up a “document or record” related to the proceeding during that violent assault. The statutory text does not require such a counterintuitive result.

The mention of Reffitt is surely included not just to embarrass Nichols by demonstrating the absurdity of his result. It is tactical.

Right now, there are two obstruction cases that might be the first to be appealed to the DC Circuit. This decision, or Guy Reffitt’s conviction, including on the obstruction count.

By asking Nichols to reconsider, DOJ may have bought time such that Reffitt will appeal before they would appeal Nichols’ decision. But by including language about Reffitt’s threats to lawmakers, DOJ has ensured not just the Reffitt facts and outcome will be available if and when they do appeal, but so would (if they are forced to appeal this decision) a Nichols decision upholding the absurd result that Reffitt didn’t obstruct the vote certification. Including the language puts him on the hook for it if he wants to force DOJ to appeal his decision.

I said in my post on Nichols’ opinion that DOJ probably considered themselves lucky that Nichols had argued for such an absurd result.

They may count themselves lucky that this particular opinion is not a particularly strong argument against their application. Nichols basically argues that intimidating Congress by assaulting the building is not obstruction of what he concedes is an official proceeding.

By including Reffitt in their motion for reconsideration, DOJ has made it part of the official record if and when they do appeal Nichols’ decision.

This would be a dick-wagging filing even absent the likelihood that Nichols has some awareness of Ginni Thomas’ antics and possibly even Eastman’s. It holds Nichols to account for blowing off virtually all the opinions of his colleagues, including fellow Trump appointees Dabney Friedrich and Tim Kelly, forcing him to defend his stance as the outlier it is.

But that is all the more true given that there’s now so much public evidence that Nichols’ deviant decision might have some tie to his personal relationship with the Thomases and even the non-public evidence of Ginni’s own role.

Plus, by making any appeal of this opinion — up to the Supreme Court, possibly — pivot on how and why Nichols came up with such an outlier opinion, it would make Justice Thomas’ participation in the decision far more problematic.

Carl Nichols, March 7, 2022, Miller

David Carter, March 28, 2022, Eastman

Opinions upholding obstruction application:

- Dabney Friedrich, December 10, 2021, Sandlin

- Amit Mehta, December 20, 2021, Caldwell

- James Boasberg, December 21, 2021, Mostofsky

- Tim Kelly, December 28, 2021, Nordean

- Randolph Moss, December 28, 2021, Montgomery

- Beryl Howell, January 21, 2022, DeCarlo

- John Bates, February 1, 2022, McHugh

- Colleen Kollar-Kotelly, February 9, 2022, Grider

- Richard Leon (by minute order), February 24, 2022, Costianes

- Christopher Cooper, February 25, 2022, Robertson

- Rudolph Contreras, announced March 8, released March 14, Andries

- Paul Friedman, March 19, Puma