On the Definition of Dragnet “Identifier”

Last month, I noted that ODNI failed to redact a reference to Verizon in one of the phone dragnet primary orders, which helped to confirm that Verizon was the provider ordered to provide only its domestic or one-end domestic call records to NSA under this order.

I’d like to look at another redaction fail (also, IIRC, pointed out to me Michael) from that document dump.

In the February 25, 2010 order, part of the footnote describing what identifiers NSA can use to contact chain was left unredacted.

The footnote starts on the previous page; this is the end of the description (the big redaction below it modifies one of the terms in the list of terror groups associations).

Given all the discussion about whether NSA does or does not collect cell phone data, I think it of particular interest that IMSI and IMEI — two ways to identify cell phone users — appear in this footnote. It’s actually not clear whether their inclusions mean they can or cannot be used as identifiers.

But there’s reason to believe the footnote says they can be used as identifiers.

The footnote first appeared in the March 5, 2009 order — the first written after Judge Reggie Walton started trying to clean up the dragnet mess.

By that point, NSA had informed Walton that an additional querying tool had regularly accessed the 215 dragnet to perform analysis of certain identifiers.

If an analyst conducted research supported by [redacted] the analyst would receive a generic notification that NSA’s signals intelligence (“SIGINT”) databases contained one or more references to the telephone identifier in which the analyst was interested; a count of how many times the identifier was present in SIGINT databases; the dates of the first and last call events associated with the identifier; a count of how many other unique telephone identifiers had direct contact with the identifier that was the subject of the analyst’s research; the total number of calls made to or from the telephone identifier that was the subject of the analyst’s research; the ratio of the count of total calls to the count of unique contacts; and the amount of time it took to process the analyst’s query.

But this was before NSA explained it treated all correlated identifiers for a particular RAS-approved person as RAS-approved,

The end-to-end review revealed the fact that NSA’s practice of using correlated selectors to query the BR FISA metadata had not been fully described to the Court. A communications address or selector, is considered correlated with other communications addresses when each additional address is shown to identify the same communicant(s) as the original address.

Though it had provided some kind of description of this practice in an August 18, 2008 filing that almost certainly served as back-up for the August 19, 2008 order that first started specifically ordering IMSI and IMEI data.

A description of how [redacted] is used to correlate [redacted] was included in the government’s 18 August 2008 filing to the FISA Court, While NSA previously described to the FISC the ractice of using correlated selectors as seeds, the FISC never addressed whether [redacted] correlated selectors met the RAS standard when any one of the correlated selectors met the RAS standard. A notice was filed with the FISC can this issue on 15 June 2009.

All of which is to say that several of the items discussed during the 2009 review pertained to how NSA tracked identities over time, particularly phone-based identities that spanned multiple cell phones.

Which would explain why it would want to track both phone numbers themselves, but especially the handset and SIM identifiers (though in the case of burner phone “correlation,” those details wouldn’t help to make a match).

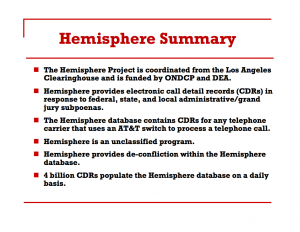

None of this should be surprising. As I said, it would be shocking if the nation’s counterterrorism professionals accepted a dragnet with less functionality than the one available to DEA under AT&T’s Hemisphere program, and a key part of that program involves matching cell phone identities (though remember, Hemisphere at least used to permit tracking of geolocation, too).

But assuming that footnote defining “identifier” affirmatively includes IMSI and IMEI as potential identifiers, which would seem logical, it’s yet one more data point showing how central the use of cell phones is to the dragnet.

That still doesn’t mean the NSA collected cell phone data, or collected it from providers besides AT&T and Sprint. But it sure seems to indicate an priority on such data.