The Mark Zaid Materials from the Jeffrey Sterling Trial

Because he just formed a new whistleblower group with John Napier Tye, there as been renewed interest in allegations an FBI Agent made during the Jeffrey Sterling case about attorney Mark Zaid. But there was actually a second detail regarding Zaid released just after the trial that has not been publicly reported: Zaid was interviewed by the FBI, twice, and was even interviewed before Sterling himself was.

I asked Zaid whether he was obligated to do the FBI interviews on Twitter but got no response. I think it’s possible FBI asked to interview him as much because the Senate Intelligence Committee was refusing to cooperate in the investigation as anything else; at the time, FBI considered SSCI staffer Bill Duhnke a more likely suspect than Sterling (and it’s not clear they ever ruled him out).

Let me be clear: I’m posting these materials to make the full context of them accessible. Zaid has not explained these, but he has promised repeatedly there is an explanation for them. As noted, there may be a perfectly logical explanation that has as much to do with Senate privileges as it does with attorney-client.

In any case, these materials are just what was directly related to the criminal case. The criminal investigation actually interacted with events in Sterling’s EEO lawsuit — which is what Zaid was primarily representing Sterling on in 2003 — in even more interesting ways I may return to.

Special Agent Ashley Hunt’s accusations

The following accusation came in prosecutor Eric Olshan’s redirect of Ashley Hunt, the FBI witness in the trial, after Sterling’s lawyers had demonstrated that the investigation was narrowly focused on Sterling without questioning some of the other possible witnesses in the case.

Q. When you initiated the investigation, I believe you testified it was in April of 2003?

A. That’s correct.

Q. At the time when you initiated your investigation concerning unauthorized disclosure of classified information to James Risen, did you learn any information regarding Mark Zaid and Mr. Krieger that, that directed your investigation?

A. I did.

MR. MAC MAHON: Your Honor, objection. That door was not opened as to Mr. Sterling’s prior lawyers.

MR. OLSHAN: Your Honor, this is about why —

THE COURT: Again, the scope of the investigation, what was done and not done, was clearly part of the cross. I’m going to allow it, excuse me, on redirect; and if there needs to be recross on that, you’ll be allowed to. Go ahead.

MR. MAC MAHON: Thank you, Your Honor.

BY MR. OLSHAN: Q. What did you learn at the outset of your investigation about information from Mr. Krieger and Zaid that helped you direct your investigation and focus it?

A. When I opened my investigation on April 8, 2003, my investigation was based on a report I received from the CIA dated April 7, 2003. In that report, the CIA provided information about the fact —

MR. MAC MAHON: Your Honor, that’s hearsay.

THE COURT: Wait.

MR. OLSHAN: Your Honor, this is not for the truth. It’s why she took the actions.

THE COURT: It explains why she is acting, takes the investigative tacks that she does, so I’m going to overrule the objection. It’s not hearsay.

BY MR. OLSHAN: Q. You may continue, Special Agent Hunt.

A. The CIA advised that on February 24, 2003, it was contacted by Mark Zaid and Roy Krieger. They told the CIA on February 24 that a client of theirs had contacted them on February 21, 2003, and that that client, that unnamed client at the time voiced his concerns about an operation that was nuclear in nature, and he threatened to go to the media.

Q. Did you later learn who that client was from Mr. Zaid and Mr. Krieger in the course of your investigation?

A. I did.

Q. Did those facts help you focus the direction of your investigation?

A. They did.

Q. And who did you learn was the client of Mr. Krieger and Mr. Zaid?

A. Jeffrey Sterling.

On recross, Sterling lawyer Edward McMahon worked to undercut the revelation by having Hunt describe how, when she wrote up a memo on the case on April 12, 2003, she believed it unlikely he was the leaker.

Q. Okay. And you had written about Mr. Sterling in 2003, hadn’t you, the same time you’re telling in answer to Mr. Olshan’s questions that you were hearing some hearsay about Mr. Sterling’s lawyers?

A. I’m sorry, what’s the question?

Q. You said you had heard some hearsay that Mr. Sterling’s lawyers were talking about him at the CIA, correct?

A. What I said is that his attorneys went to the CIA on February 24. At that time, they did not name Jeffrey Sterling.

Q. All right. But on April 12 of 2003, you wrote a memo about Mr. Sterling, and you said that it was unlikely that it was Mr. Sterling who was the leak, correct?

A. If I wrote that at that time, then that was based on the information I had at that time.

Q. Right. You said that it’s unlikely that someone who has already attempted to settle an EEO lawsuit for a few hundred thousand dollars would choose to attack and enrage the organization from which he seeks but has not yet received a settlement. That’s your writing, isn’t it?

A. I don’t know. You haven’t shown me the document.

Q. And you also in the same document dismiss your concerns about Mr. Zaid and Krieger, correct? You don’t remember that?

A. I don’t know. It was 12 years ago.

Q. And in the last 12 years, you still haven’t come up with any proof that Mr. Sterling ever talked to Mr. Risen about Classified Program No. 1 or Merlin, right?

A. Correct.

Thus far, the timeline looks like this:

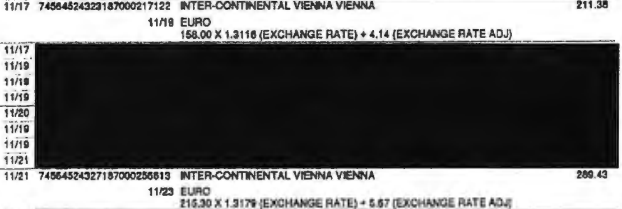

February 21: Alleged contact between Sterling and Zaid (not stated whether this is phone call or email, which would show up in call records available with a relevance standard)

February 24: Alleged call from Zaid and his partner warning that one of their clients would leak

April 7: CIA referral includes their claim about Zaid call

April 8: Hunt opens investigation

April 12: Hunt writes memo dismissing likelihood that Sterling is leaker

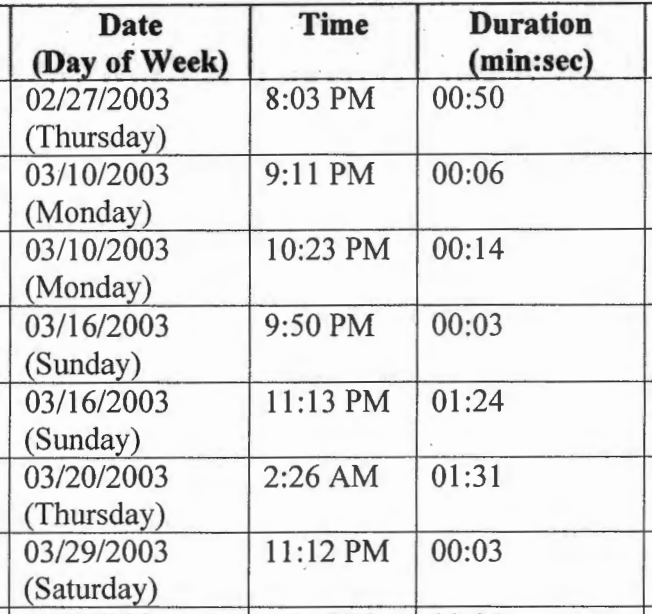

The FBI Interview Dates

Now consider the dates of the 2003 FBI 302s included in these two CIPA letters (the names with the first initial last name are CIA witnesses; it’s unclear whether that’s true of the entirely redacted names).

April 12: Redacted name

April 12: Robert J. E

April 12: Bob S

April 13: Redacted name

April 13: Redacted name

April 14: Bill H (almost certainly Bill Harlow, CIA’s then spox)

April 18: Mark Zaid (three page 302)

April 28: Bill H (again, almost certain Harlow)

May 7: Redacted name

May 9: Redacted name

June 19: Sterling

June 26: Bob S (Sterling’s supervisor)

July 18: Redacted name

July 21: Thomas H

August 1: David C

August 13: Redacted name

August 14: Diane F

That is, the memo where Hunt said she didn’t think Sterling was the leaker was written either before she had done any interviews, or after she had done just the first CIA ones (including with Sterling’s boss, who definitely blamed Sterling). The first round of interviews appear to be primarily or all CIA witnesses.

And the next interview — at least among those that Sterling’s defense thought they might use at trial — was Zaid. Zaid’s interview, in fact, was months before Sterling’s. The second letter shows a second Zaid interview on September 2, 2010.

To emphasize: Sterling’s lawyers requested these FBI interviews be available for trial, not the prosecution. It’s unclear whether they did that because the interviews would have helped them, or because (as was the case with virtually all the other witnesses) they thought they might need to draw on those interviews for cross-examination.

But unless there’s some wildly egregious error in these files, Mark Zaid did two interviews with the FBI before he — obligated by subpoena, he said repeatedly — testified before the grand jury on September 22, 2010.