Working Thread, Apple Response

Apple’s response to the phone back door order is here.

(1) Apple doesn’t say it, but some people at Apple — probably including people who’d have access to this key (because they’d be involved in using it, which would require clearance) — had to have been affected in the OPM hack.

(2) Remember as you read it that Ted Olson lost his wife on 9/11.

(3) Several members of Congress — including ranking HPSCI member Adam Schiff — asked questions in hearings about this today.

(4) Apple hoists Comey on the same petard that James Orenstein did.

(8) More hoisting on petarding, in this case over DOJ generally and Comey specifically choosing not to seek legislation to modify CALEA.

(11) Apple beats up FBI for fucking up.

Unfortunately, the FBI, without consulting Apple or reviewing its public guidance regarding iOS, changed the iCloud password associated with one of the attacker’s accounts, foreclosing the possibility of the phone initiating an automatic iCloud back-up of its data to a known Wi-Fi network, see Hanna Decl. Ex. X [Apple Inc., iCloud: Back up your iOS device to iCloud], which could have obviated the need to unlock the phone and thus for the extraordinary order the government now seeks.21 Had the FBI consulted Apple first, this litigation may not have been necessary.

(11) This is awesome, especially coming as it does from Ted Olson, who Comey asked to serve as witness for a key White House meeting after the Stellar Wind hospital confrontation.

(12) This is the kind of information NSA would treat as classified, for similar reasons.

Although it is difficult to estimate, because it has never been done before, the design, creation, validation, and deployment of the software likely would necessitate six to ten Apple engineers and employees dedicating a very substantial portion of their time for a minimum of two weeks, and likely as many as four weeks. Neuenschwander Decl. ¶ 22. Members of the team would include engineers from Apple’s core operating system group, a quality assurance engineer, a project manager, and either a document writer or a tool writer.

(16) I’ll have to double check, but I think some of this language quotes Orenstein directly.

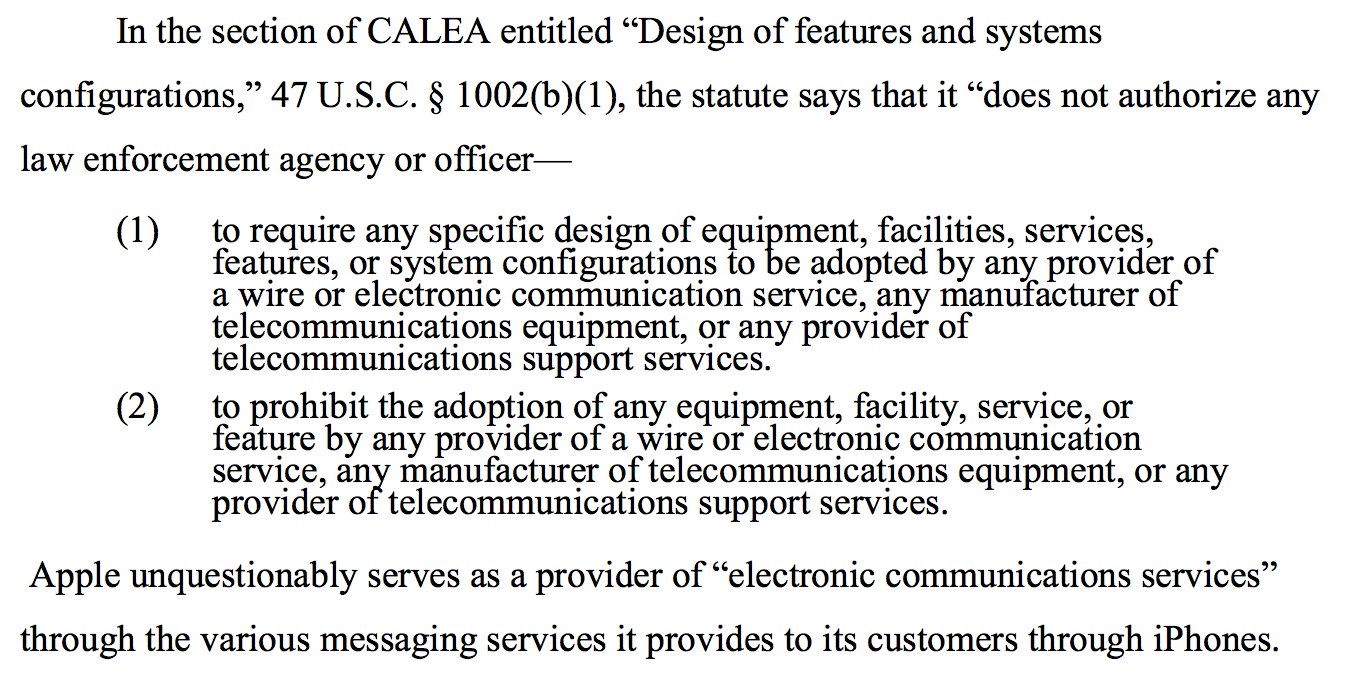

Congress knows how to impose a duty on third parties to facilitate the government’s decryption of devices. Similarly, it knows exactly how to place limits on what the government can require of telecommunications carriers and also on manufacturers of telephone equipment and handsets. And in CALEA, Congress decided not to require electronic communication service providers, like Apple, to do what the government seeks here. Contrary to the government’s contention that CALEA is inapplicable to this dispute, Congress declared via CALEA that the government cannot dictate to providers of electronic communications services or manufacturers of telecommunications equipment any specific equipment design or software configuration.

(16) This discussion of what Apple is has ramifications for USA Freedom Act, which the House report said only applied to “phone companies” (though the bill says ECSPs).

(18) Loving Apple wielding Youngstown against FBI.

Nor does Congress lose “its exclusive constitutional authority to make laws necessary and proper to carry out the powers vested by the Constitution” in times of crisis (whether real or imagined). Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579, 588–89 (1952). Because a “decision to rearrange or rewrite [a] statute falls within the legislative, not the judicial prerogative[,]” the All Writs Act cannot possibly be deemed to grant to the courts the extraordinary power the government seeks. Xi v. INS, 298 F.3d 832, 839 (9th Cir. 2002).

(20) Reading this passage on how simple pen register rulings shouldn’t apply to far more intrusive surveillance, I’m reminded that Olson left DOJ in 2004 before (or about the same time as) Jim Comey et al applied PRTT to conduct metadata dragnet of Americans.

In New York Telephone Co., the district court compelled the company to install a simple pen register device (designed to record dialed numbers) on two telephones where there was “probable cause to believe that the [c]ompany’s facilities were being employed to facilitate a criminal enterprise on a continuing basis.” 434 U.S. at 174. The Supreme Court held that the order was a proper writ under the Act, because it was consistent with Congress’s intent to compel third parties to assist the government in the use of surveillance devices, and it satisfied a three-part test imposed by the Court.

(22) This is one thing that particularly pissed me off about the application of NYTelephone to this case: there’s no ongoing use of Apple’s phone.

This case is nothing like Hall and Videotapes, where the government sought assistance effectuating an arrest warrant to halt ongoing criminal activity, since any criminal activity linked to the phone at issue here ended more than two months ago when the terrorists were killed.

(24) I think this is meant to be a polite way of calling DOJ’s claims fucking stupid (Jonathan Zdziarski has written about how any criminal use of this back door would require testimony about the forensics of this).

Use of the software in criminal prosecutions only exacerbates the risk of disclosure, given that criminal defendants will likely challenge its reliability. See Fed. R. Evid. 702 (listing requirements of expert testimony, including that “testimony [be] the product of reliable principles and methods” and “the expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case,” all of which a defendant is entitled to challenge); see also United States v. Budziak, 697 F.3d 1105, 1111–13 (9th Cir. 2012) (vacating order denying discovery of FBI software); State v. Underdahl, 767 N.W.2d 677, 684–86 (Minn. 2009) (upholding order compelling discovery of breathalyzer source code). The government’s suggestion that Apple can destroy the software has clearly not been thought through, given that it would jeopardize criminal cases. See United States v. Cooper, 983 F.2d 928, 931–32 (9th Cir. 1993) (government’s bad-faith failure to preserve laboratory equipment seized from defendants violated due process, and appropriate remedy was dismissal of indictment, rather than suppression of evidence). [my emphasis]

(25) “If you outlaw encryption the only people with encryption will be outlaws.”

And in the meantime, nimble and technologically savvy criminals will continue to use other encryption technologies, while the law-abiding public endures these threats to their security and personal liberties—an especially perverse form of unilateral disarmament in the war on terror and crime.

(26) The parade of horribles that a government might be able to coerce is unsurprisingly well-chosen.

For example, under the same legal theories advocated by the government here, the government could argue that it should be permitted to force citizens to do all manner of things “necessary” to assist it in enforcing the laws, like compelling a pharmaceutical company against its will to produce drugs needed to carry out a lethal injection in furtherance of a lawfully issued death warrant,25 or requiring a journalist to plant a false story in order to help lure out a fugitive, or forcing a software company to insert malicious code in its autoupdate process that makes it easier for the government to conduct court-ordered surveillance. Indeed, under the government’s formulation, any party whose assistance is deemed “necessary” by the government falls within the ambit of the All Writs Act and can be compelled to do anything the government needs to effectuate a lawful court order. While these sweeping powers might be nice to have from the government’s perspective, they simply are not authorized by law and would violate the Constitution.

(30) “Say, why can’t NSA do this for you?”

Moreover, the government has not made any showing that it sought or received technical assistance from other federal agencies with expertise in digital forensics, which assistance might obviate the need to conscript Apple to create the back door it now seeks.

(33) Love the way Apple points out what I and others have: this phone doesn’t contain valuable information, and if it does, Apple probably couldn’t get at it.

Apple does not question the government’s legitimate and worthy interest in investigating and prosecuting terrorists, but here the government has produced nothing more than speculation that this iPhone might contain potentially relevant information.26 Hanna Decl. Ex. H [Comey, Follow This Lead] (“Maybe the phone holds the clue to finding more terrorists. Maybe it doesn’t.”). It is well known that terrorists and other criminals use highly sophisticated encryption techniques and readily available software applications, making it likely that any information on the phone lies behind several other layers of non-Apple encryption. See Hanna Decl. Ex. E [Coker, Tech Savvy] (noting that the Islamic State has issued to its members a ranking of the 33 most secure communications applications, and “has urged its followers to make use of [one app’s] capability to host encrypted group chats”).

26 If the government did have any leads on additional suspects, it is inconceivable that it would have filed pleadings on the public record, blogged, and issued press releases discussing the details of the situation, thereby thwarting its own efforts to apprehend the criminals. See Douglas Oil Co. of Cal. v. Petrol Stops Nw., 441 U.S. 211, 218-19 (1979) (“We consistently have recognized that the proper functioning of our grand jury system depends upon the secrecy of grand jury proceedings. . . . [I]f preindictment proceedings were made public, many prospective witnesses would be hesitant to come forward voluntarily, knowing that those against whom they testify would be aware of that testimony. . . . There also would be the risk that those about to be indicted would flee, or would try to influence individual grand jurors to vote against indictment.”).

(35) After 35 pages of thoroughgoing beating, Apple makes nice.

Apple has great respect for the professionals at the Department of Justice and FBI, and it believes their intentions are good.

(PDF 56) Really looking forward to DOJ’s response to the repeated examples of this point, which is likely to be, “no need to create logs because there will never be a trial because the guy is dead.” Which, of course, will make it clear this phone won’t be really useful.

Moreover, even if Apple were able to truly destroy the actual operating system and the underlying code (which I believe to be an unrealistic proposition), it would presumably need to maintain the records and logs of the processes it used to create, validate, and deploy GovtOS in case Apple’s methods ever need to be defended, for example in court. The government, or anyone else, could use such records and logs as a roadmap to recreate Apple’s methodology, even if the operating system and underlying code no longer exist.

(PDF 62) This is really damning. FBI had contacted Apple before they changed the iCloud password.

(PDF 62) Wow. They did not ask for the iCloud data on the phone until January 22, 50 days after seizing the phone and 7 days before warrant expired.