“Somewhat Convoluted:” Debunking the Judge Cannon Claims

Before I went to sleep last night, I suggested there was some suspense about whether journalists would accurately report the power grab Judge Aileen Cannon made yesterday. Who was I kidding? Rather than report what happened, virtually all news coverage simply quoted what Cannon claimed she had done. Not only didn’t the press call out Cannon’s own misrepresentations, but they introduced some of their own.

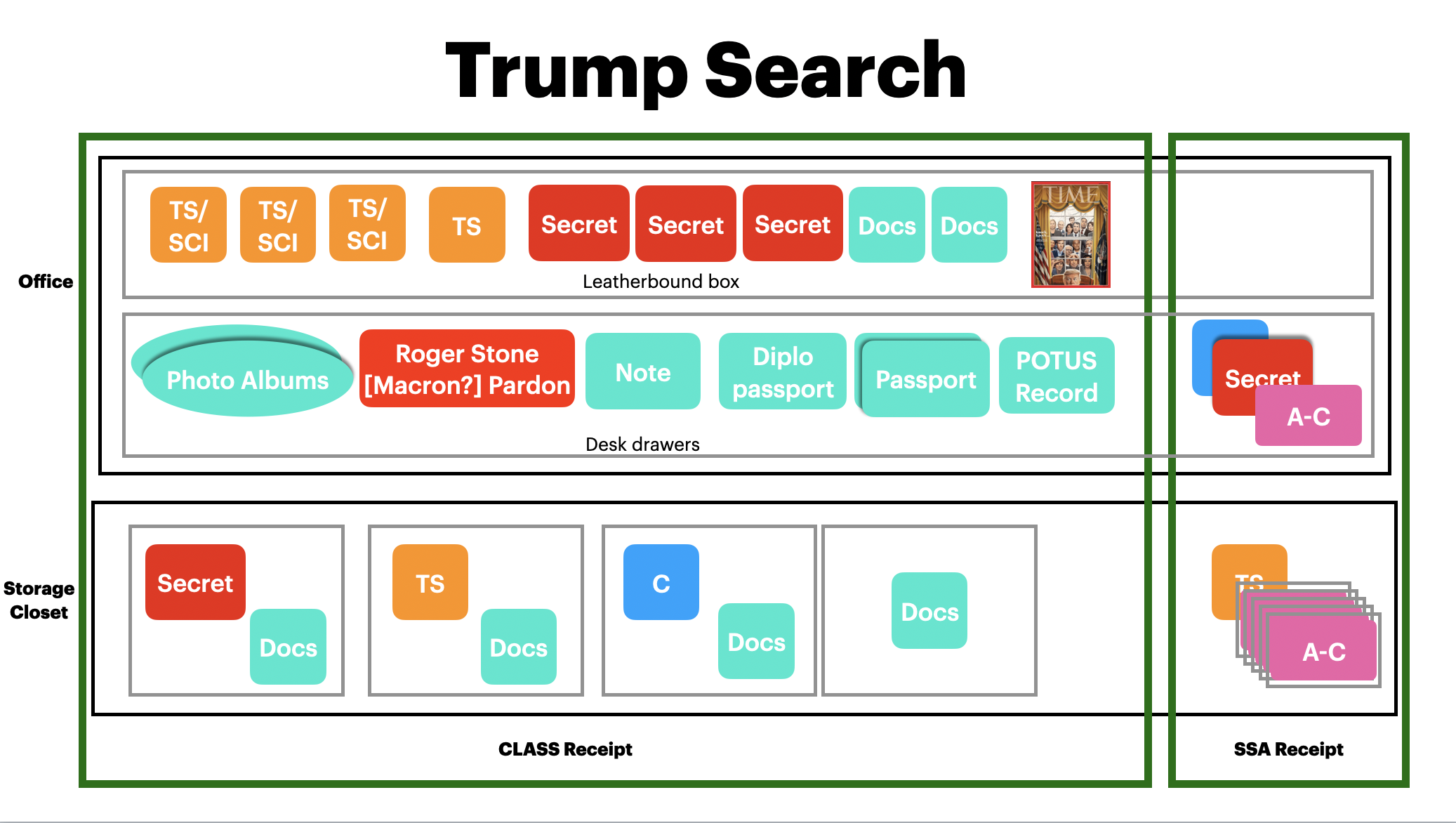

First, some outlets had suggested that Raymond Dearie had set really aggressive deadlines and Cannon simply altered them. That’s not really accurate. Cannon definitely tweaked with how Dearie would deal with the disputes (mandating a single report from Trump rather than cascading productions, a decision that Trump will cite next month when they ask for an extension). But her original order didn’t mandate any interim deadlines on the review itself (meaning, she can’t say the delay in hiring a vendor changed her own timeline); she just gave Raymond Dearie deadlines and timeframes during which the parties could challenge his decisions. The new interim deadlines she provided are premised on when Trump first receives the materials, so the delay Trump introduced by stalling on a vendor may not affect the process all that much. Dearie’s own deadlines were timed to meet Cannon’s deadline. So effectively, Cannon has simply arbitrarily extended her own deadline by 17 days, from November 30 to December 16.

Finally, in light of delays in securing an appropriate vendor to scan and make available the Seized Materials to Plaintiff and the Special Master, and recognizing the more precise quantification of the implicated pages of material [ECF No. 123 p. 1 (describing that the 11,000 documents approximate 200,000 pages of materials)], the Court hereby extends the end date for completion of the Special Master’s review and classifications from the prior date of November 30, 2022 [ECF No. 91 p. 5], to December 16, 2022. This modest enlargement is necessary to permit adequate time for the Special Master’s review and recommendations given the circumstances as they have evolved since entry of the Appointment Order.

As I note below, that happens to delay the end of Dearie’s work until after such time as the appeal will be fully briefed.

Cannon bases her timeline on three things. First, there’s the delay Trump introduced in getting a vendor (a delay Jim Trusty telegraphed at the hearing before Dearie). Cannon currently envisions the two sides having to agree on a vendor, so Trump may be able to delay the process further still.

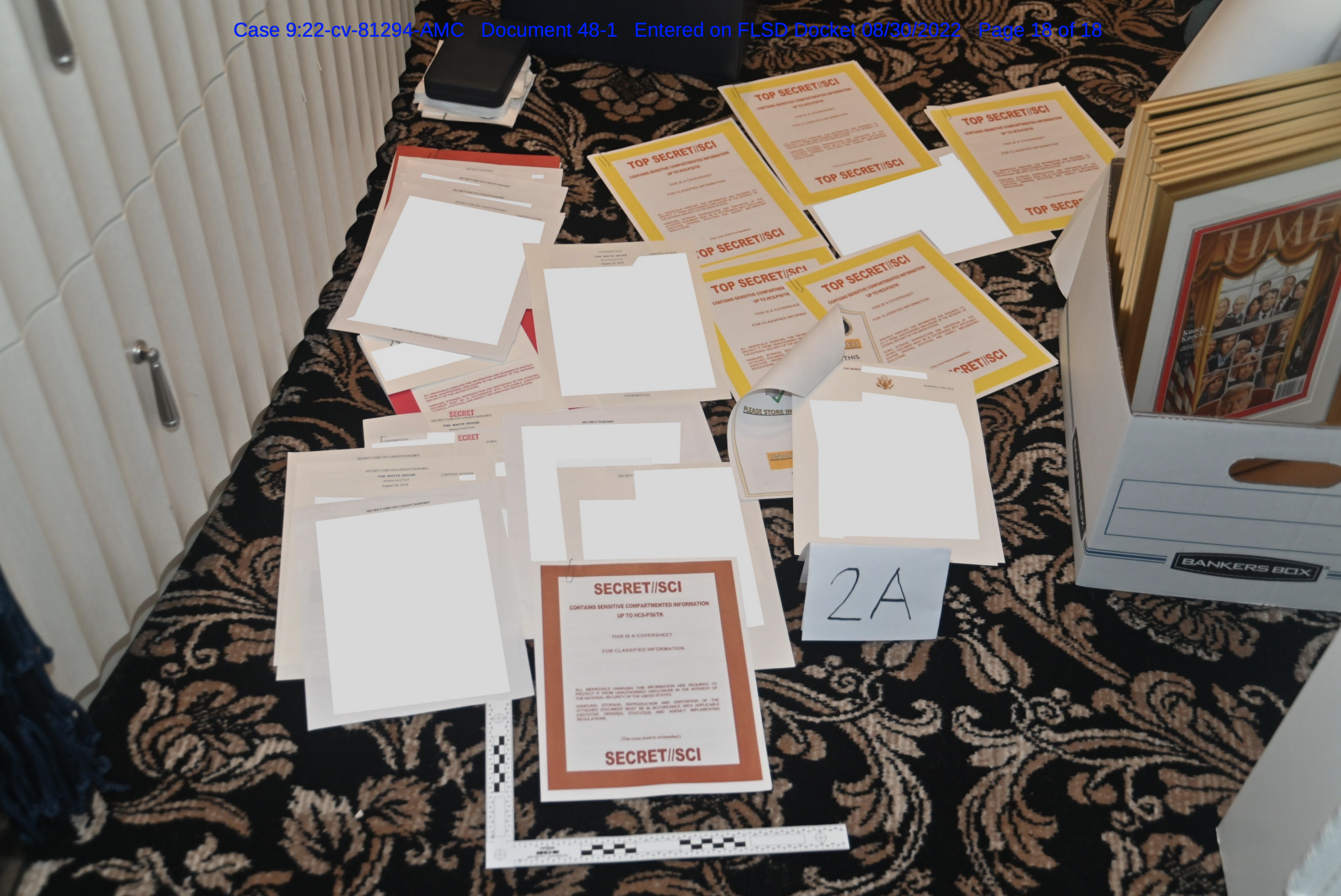

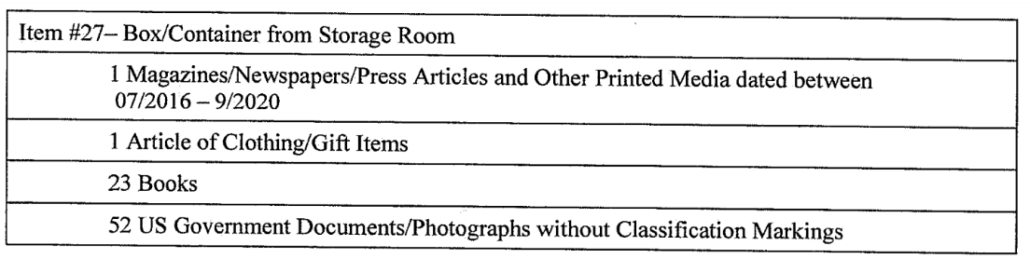

Cannon also bought Trump’s claim there are 200,000 pages of materials. As I’ll show in a follow-up, she timed her order in such a way as to prevent DOJ from correcting this claim. I suspect it comes from a draft work order DOJ gave to Trump, but we shall see if and when DOJ explains that it’s impossible for there to be 200,000 documents in the 27 seized boxes plus Trump’s desk drawers.

Cannon also has decided that it will take three weeks to do the review based off her claim that it took DOJ three weeks to do a preliminary review of the seized material.

For context, it took Defendant’s Investigative Team approximately three weeks to complete its preliminary review of the Seized Material [ECF No. 39 p. 1].

She bases that off the interim status report from DOJ, which doesn’t say how long the review took. Rather, it says,

As of the date of this filing, the investigative team has completed a preliminary review of the materials seized pursuant to the search warrant executed on August 8, 2022, with the exception of any potentially attorney-client privileged materials that, pursuant to the filter protocols set forth in the search warrant affidavit, have not been provided to the investigative team.

DOJ would have said the same thing whether they finished their review minutes before filing this status report or two weeks earlier. Cannon simply invented the claim that DOJ had only just finished the review on August 30, three weeks after the seizure.

Cannon likewise misrepresents the nature of Trump’s objection to the inventory review and what the inventory review would have been (and reporters made her misrepresentation worse).

In addition to requiring Defendant to attest to the accuracy of the Inventory, the Plan also requires Plaintiff, on or before September 30, 2022, to lodge objections to the Inventory’s substantive contents.2

[snip]

Plaintiff objects to the pre-review Inventory objection requirement, citing the Court’s Order Appointing Special Master [ECF No. 91] and the current inability to access the Seized Materials [ECF No. 123-1 p. 1].

[snip]

There shall be no separate requirement on Plaintiff at this stage, prior to the review of any of the Seized Materials, to lodge ex ante final objections to the accuracy of Defendant’s Inventory, its descriptions, or its contents.

2 The Special Master’s Interim Report No. 1 modified this deadline to October 7, 2022 [ECF No. 118 p. 2].

Here’s what Trump’s objection actually said:

To help find facts, the appointing order authorized a declaration or affidavit by a Government official regarding the accuracy of the Detailed Property Inventory [ECF 39-1] as to whether it represents a full and accurate accounting of the property seized from Mara-Lago. Appointing Order ¶ 2(a). The Appointing Order contemplated no corresponding declaration or affidavit by Plaintiff, and because the Special Master’s case management plan exceeds the grant of authority from the District Court on this issue, Plaintiff must object. Additionally, the Plaintiff currently has no means of accessing the documents bearing classification markings, which would be necessary to complete any such certification by September 30, the currently proposed date of completion. [my emphasis]

The material he couldn’t review was limited to documents with classification markings, not the documents as a whole. And as Cannon notes in a footnote (there’s a reason it’s in the footnote, which I’ll come back to in a follow-up), Dearie had given Trump the same four days after receiving the materials to review the inventory after he adjusted the deadlines. In spite of the fact that Dearie’s most recent order only envisioned this verification to happen after Trump got the material, Cannon calls it a “pre-review” and “ex ante” process, suggesting Trump would have had to verify the inventory blind.

Perhaps Cannon’s most cynical move, however, came in her order dismissing Dearie’s suggestion that the two sides might have to brief whether Trump should file a Rule 41(g) in this court or before Bruce Reinhart.

As explained in the Court’s previous Order, Plaintiff properly brought this action in the district where Plaintiff’s property was seized [see ECF No. 64 p. 7 n.7 (citing Fed. R. Crim. P. 41(g); United States v. Wilson, 540 F.2d 1100, 1104 (D.C. Cir. 1976); In the Matter of John Bennett, No. 12-61499-CIV-RSR, ECF No. 1 (S.D. Fla. July 31, 2012))].

The 11th Circuit has already ruled that intervening absent any evidence of callous disregard for Trump’s rights was an abuse of discretion.

We begin, as the district court did, with “callous disregard,” which is the “foremost consideration” in determining whether a court should exercise its equitable jurisdiction. United States v. Chapman, 559 F.2d 402, 406 (5th Cir. 1977). Indeed, our precedent emphasizes the “indispensability of an accurate allegation of callous disregard.” Id. (alteration accepted and quotation omitted).

Here, the district court concluded that Plaintiff did not show that the United States acted in callous disregard of his constitutional rights. Doc. No. 64 at 9. No party contests the district court’s finding in this regard. The absence of this “indispensab[le]” factor in the Richey analysis is reason enough to conclude that the district court abused its discretion in exercising equitable jurisdiction here. Chapman, 559 F.2d at 406

Even ignoring that two Trump appointees have already told Cannon she was wrong, the sentence before the one Cannon cites here notes the absurdity of filing for a Special Master and a Rule 41(g) motion in the same effort, calling it “somewhat convoluted.”

As previewed, Plaintiff initiated this action with a hybrid motion that seeks independent review of the property seized from his residence on August 8, 2022, a temporary injunction on any further review by the Government in the meantime, and ultimately the return of the seized property under Rule 41(g) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. 6 Though somewhat convoluted, this filing is procedurally permissible7 and creates an action in equity.

Yet even after straining to approve this in her first review and then getting smacked down by the 11th, Cannon still persists in envisioning that she’ll be able to take government property and give it to Trump.

I suspect Cannon’s wrong about at least one more thing — whether Trump has complied with his deadline to mark privileged material. These issues, however, all exhibit the same dishonesty we’ve seen in the past.

Yet the very same press that Judge Cannon is blowing off nevertheless failed to identify any of these problems.

Current Schedule

September 26: Trump provides designations on potentially privileged materials

October 3: Both sides identify areas of dispute on potentially privileged designations

October 5: Finalize a vendor (Cannon fashions this as a common agreement, giving Trump ability to delay some more)

October 13: DOJ provides materials to Trump (Cannon does not note this does not include classified documents)

By October 14: DOJ provides notice of completion that Trump has received all seized documents

October 19: Deadline for DOJ appeal to 11th Circuit

21 days after notice of completion (November 4): Trump provides designations to DOJ

November 8: Election Day

10 days after receiving designations (November 14): Both sides provide disputes to Dearie

30 days after DOJ appeal (November 18): Trump reply to 11th Circuit

21 days after Trump reply (December 9): DOJ reply to 11th Circuit

December 16: Dearie provides recommendations to Cannon

January 3: New Congress sworn in

No deadline whatsoever: Cannon rules on Dearie’s recommendations

Seven days after Cannon’s no deadline whatsoever ruling: Trump submits Rule 41(g) motion

Fourteen days after Cannon’s no deadline whatsoever ruling: DOJ responds to Rule 41(g) motion

Seventeen days after Cannon’s no deadline whatsoever ruling: Trump reply on Rule 41(g)