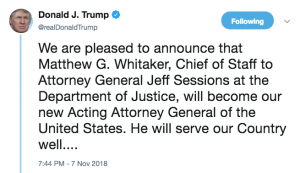

As I’ve often said, Trump departed from his usual habit by hiring Emmet Flood, someone who is eminently qualified to help the President (or, as he did with Cheney, Vice President) stave off legal jeopardy from a Special Counsel or Congress. Which is why I’m trying to figure out whether the legal morass Trump created — presumably on Flood’s advice, given that Flood is serving as both the Mueller investigation White House Counsel lead and, until Pat Cipollone gets fully cleared, White House Counsel generally — by forcing Jeff Sessions’ resignation and replacing him with Matt Whitaker.

It’s not clear when Sessions’ authority ended

Start with the fact that it’s not clear when Jeff Sessions stopped acting as Attorney General. As numerous people have noted, he didn’t date the copy of his resignation letter that got released publicly.

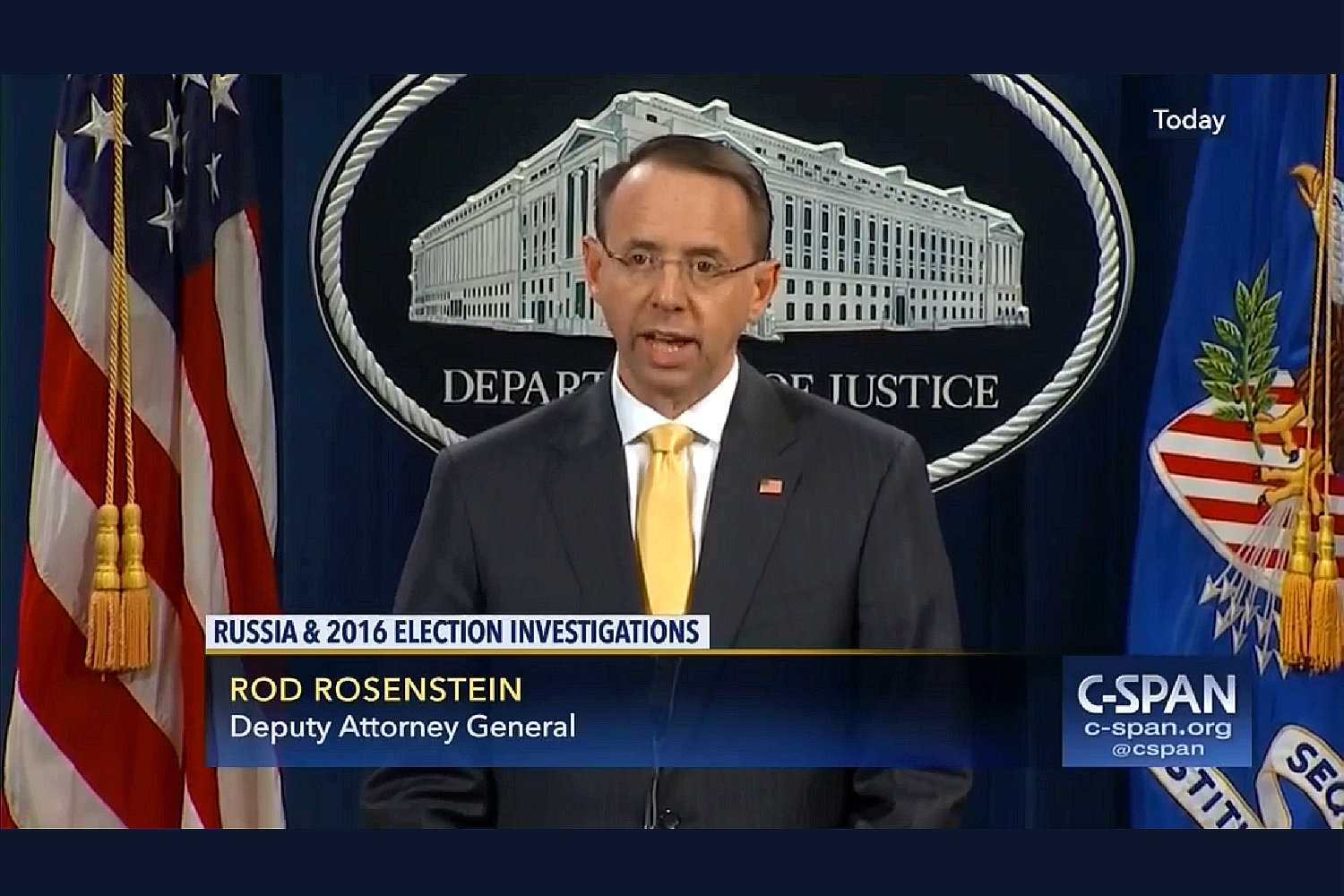

He left DOJ in ceremonial fashion just after 5 PM on Wednesday night, which would suggest he may have remained AG until that time. If that’s right, then anything that Mueller and Rosenstein did that day would still operate under the older authority.

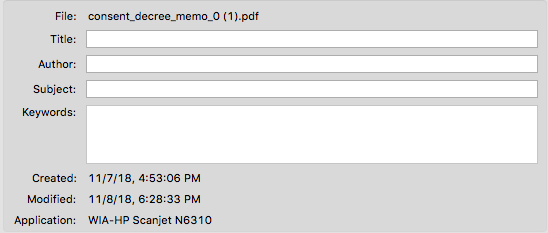

Indeed, DOJ issued an order under Sessions’ authority, imposing new limits on consent decrees used to reign in abusive local police departments, yesterday evening, a full day after he departed. He initialed it (dated 11/7/18), but the metadata on it shows the document wasn’t created until almost 5PM on Wednesday and was modified over a full day after that. (h/t zedster)

So he was at least still AG sometime after 4:53PM on Wednesday — and possibly well after that — or this consent decree policy is void.

Whitaker’s appointment may not be legal

Then there are the proliferating number of people — most prominently Neal Katyal and George Conway but also including John Yoo and Jed Sugarman — who believe his appointment is unconstituional.

There are two bases on which this might be true. First, the forced resignation of Jeff Sessions may in fact be a legal firing, something the House Judiciary Democrats are arguing with increasing stridency, most recently in a letter to Bob Goodlatte asking that he hold an emergency hearing on Sessions’ ouster, support legislation protecting Mueller, and join in requests for information about the ouster from the White House and DOJ. If Sessions was fired, there’s little question that Trump can only replace him with someone who is Senate confirmed.

But Katyal, Conway, and others argue that because the AG is a principal officer, whoever serves in that position must be Senate confirmed. Significantly, the Katyal/Conway argument begins by throwing what Steven Calabresi has said back at conservatives.

What now seems an eternity ago, the conservative law professor Steven Calabresi published an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal in May arguing that Robert Mueller’s appointment as special counsel was unconstitutional. His article got a lot of attention, and it wasn’t long before President Trump picked up the argument, tweeting that “the Appointment of the Special Counsel is totally UNCONSTITUTIONAL!”

Professor Calabresi’s article was based on the Appointments Clause of the Constitution, Article II, Section 2, Clause 2. Under that provision, so-called principal officers of the United States must be nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate under its “Advice and Consent” powers.

He argued that Mr. Mueller was a principal officer because he is exercising significant law enforcement authority and that since he has not been confirmed by the Senate, his appointment was unconstitutional. As one of us argued at the time, he was wrong. What makes an officer a principal officer is that he or she reports only to the president.

This is probably why people like Yoo are joining in this argument — because if Whitaker’s appointment is legal, than a whole slew of other appointments of the kind that conservatives hate would also be legal.

Whitaker may be disabled with conflicts

Then there are Whitaker’s conflicts, which are threefold. Whitaker:

- Repeatedly claimed that the Mueller probe was out of control, in spite of the fact he had no real information to base that on

- Judged that Trump had neither “colluded” nor committed obstruction

- Not only undermined the investigation, but suggested the underlying conduct — including meeting with Russians to obtain dirt on Hillary Clinton at the June 9 meeting — was totally cool

- Served as Sam Clovis’ campaign manager in 2014; Clovis was a key player in Trump’s efforts to cozy up to the Russians in 2016 and was one of the earliest known witnesses to testify before the grand jury

CNN captures many of these statements here.

The Clovis one may be the most important. 28 CFR 45.2 requires ethics exemption or recusal if a person has a political relationship with the subject of an investigation.

[N]o employee shall participate in a criminal investigation or prosecution if he has a personal or political relationship with:

(1) Any person or organization substantially involved in the conduct that is the subject of the investigation or prosecution; or

Defining “political relationship” to include service as a principal advisor to a candidate.

Political relationship means a close identification with an elected official, a candidate (whether or not successful) for elective, public office, a political party, or a campaign organization, arising from service as a principal adviser thereto or a principal official thereof;

And, as Mueller noted in their response to Andrew Miller’s appeal, recusal would amount to a “disability” that would put the DAG back in charge.

Finally, interpreting “disability” under Section 508 to include recusal makes logical and practical sense. Section 528 requires the Attorney General to recuse himself when he has a conflict of interest. Section 508 ensures that at all times an officer is heading the Department of Justice. If the Attorney General is recused, it is necessary that someone can head the Department for that investigation. It is inconceivable that Congress intended Section 508 to reach physical disability, but not to reach legal requirements that disabled the Attorney General from participating in certain matters.

Whitaker’s former company is under FBI investigation

Then there’s the news that a company for which Whitaker provided legal services is under criminal investigation.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation is conducting a criminal investigation of a Florida company accused of scamming millions from customers during the period that Matthew Whitaker, the acting U.S. attorney general, served as a paid advisory-board member, according to an alleged victim who was contacted by the FBI and other people familiar with the matter.

The investigation is being handled by the Miami office of the FBI and by the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, according to an email sent to the alleged victim last year by an FBI victim specialist. A recording on a phone line set up by the Justice Department to help victims said Friday the case remains active.

When Whitaker was subpoenaed, he blew it off.

Whitaker, named this week by President Trump as acting attorney general, occasionally served as an outside legal adviser to the company, World Patent Marketing, writing a series of letters on its behalf, according to people familiar with his role.

But he rebuffed an October 2017 subpoena from the Federal Trade Commission seeking his records related to the company, according to two people with knowledge of the case.

But the public record shows that when customers complained, Whitaker threatened them, invoking his background as a former US Attorney.

In emails uncovered by the FTC investigation, Whitaker personally threatened a customer who complained, according to a story in the Miami New Times that was picked up by other news outlets.

The emails the FTC obtained, in fact, suggests Whitaker used his background as a U.S. attorney to try to silence customers who claimed they were defrauded by the company and sought to take their complaints public.

In this case, Whitaker sent an intimidating email to a customer on August 25, 2015, who had contacted World Patent Marketing with his grievances and and filed a complaint with the Better Business Bureau.

The FTC docket reviewed by New Times contains an email exchange on page 362 of 400 that described what happened next.

Rather than expressing concern about the customer’s charge of being cheated, Whitaker wrote him to let him know that he, Whitaker, was “a former United States Attorney for the Southern District of Illinois…Your emails and message from today seem to be an apparent attempt at possible blackmail or extortion.”

“You also mentioned filing a complaint with the Better Business Bureau and to smear WPM’s reputation online. I am assuming you know that there could be serious civil and criminal consequences for you if that is in fact what you and your ‘group’ is doing. Understand we take threats like this quite seriously…Please conduct yourself accordingly.”

This doesn’t necessarily impact the Mueller probe itself. But it suggests that Whitaker has real corruption problems that will undermine his actions as AG.

Trump and Whitaker may have spoken about the Mueller probe — and Trump is already lying about it

Shortly after Whitaker was appointed, WaPo reported that Trump told multiple people that Whitaker was “loyal” and wouldn’t recuse.

Trump has told advisers that Whitaker is loyal and would not have recused himself from the investigation, current and former White House officials said.

Then WaPo reported that Whitaker has no intention of recusing, reporting that would necessarily predate any discussion with DOJ’s ethical advisors.

Acting attorney general Matthew G. Whitaker has no intention of recusing himself from overseeing the special-counsel probe of Russian interference in the 2016 election, according to people close to him who added they do not believe he would approve any subpoena of President Trump as part of that investigation.

[snip]

On Thursday, two people close to Whitaker said he does not plan to take himself off the Russia case. They also said he is deeply skeptical of any effort to force the president’s testimony through a subpoena.

Special counsel Robert S. Mueller III has been negotiating for months with Trump’s attorneys over the terms of a possible interview of the president. Central to those discussions has been the idea that Mueller could, if negotiations failed, subpoena the president. If Whitaker were to take the threat of a subpoena off the table, that could alter the equilibrium between the two sides and significantly reduce the chances that the president ever sits for an interview.

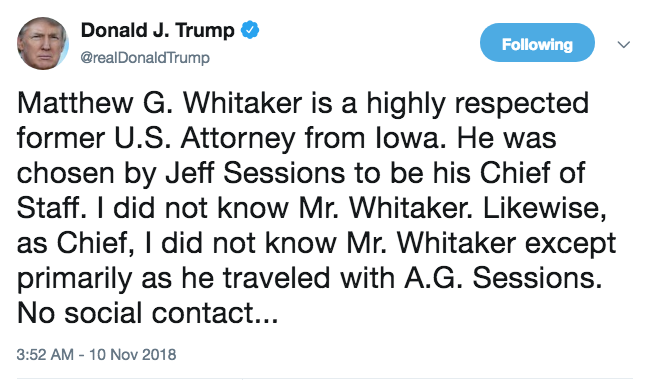

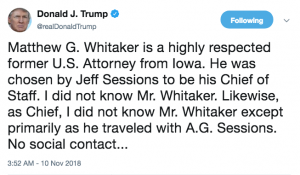

Meanwhile, when asked today, Trump claimed (in spite of all the briefings Whitaker has attended in recent weeks) that he didn’t know him, even though he went on Fox and hailed him after the most recent attempt to use him to kill the Mueller probe.

“I don’t know Matt Whitaker,” Mr. Trump told reporters as he left Washington for a weekend trip to Paris. But the president stressed that he did know Mr. Whitaker’s reputation well, calling him “a very respected man.”

[snip]

In addition, the president’s claim that he did not know Mr. Whitaker was called into question by Mr. Trump’s own words from just about a month ago, when he said in a “Fox & Friends” interview: “I can tell you Matt Whitaker’s a great guy. I mean, I know Matt Whitaker.”

Mr. Whitaker has also visited the Oval Office several times and is said to have an easy chemistry with the president, according to people familiar with the relationship. And the president has regarded Mr. Whitaker as his eyes and ears at the Justice Department.

As CNN notes, Whitaker seemed to have been actively plotting for his boss’ job since the NYT stupidly tried to get Rosenstein fired (which I suspect means Whitaker was a source for the NYT).

A source close to Sessions says that the former attorney general realized that Whitaker was “self-dealing” after reports surfaced in September that Whitaker had spoken with Kelly and had discussed plans to become the No. 2 at the Justice Department if Rosenstein was forced to resign.

In recent months, with his relationship with the President at a new low, Sessions skipped several so-called principals meetings that he was slated to attend as a key member of the Cabinet. A source close to Sessions says that neither the attorney general nor Trump thought it was a good idea for Sessions to be at the White House, so he sent surrogates.

Whitaker was one of them.

But Sessions did not realize Whitaker was having conversations with the White House about his future until the news broke in late September about Rosenstein.

All of this raises huge questions about whether Whitaker and Trump (or Kelly) had an agreement in place, that he would get this post (and shortly after be nominated for a judgeship in IA), so long as he would agree to kill the Mueller probe.

Debates over the legality of Whitaker’s appointment parallel challenges to Mueller’s authority

Then there’s the point I raised earlier today. If Whitaker’s appointment is legal, then so is Mueller’s, which undercuts one of the other efforts to undermine Mueller’s authority.

Whitaker’s nomination really undermines the arguments that Miller and Concord Management (who argued as an amici) were making about Mueller’s appointment, particularly their argument that he is a principal officer and therefore must be Senate confirmed, an argument that relies on one that Steven Calabresi made this spring. Indeed, Neal Katyal and George Conway began their argument that Whitaker’s appointment is illegal by hoisting Calabresi on his petard.

What now seems an eternity ago, the conservative law professor Steven Calabresi published an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal in May arguing that Robert Mueller’s appointment as special counsel was unconstitutional. His article got a lot of attention, and it wasn’t long before President Trump picked up the argument, tweeting that “the Appointment of the Special Counsel is totally UNCONSTITUTIONAL!”

Professor Calabresi’s article was based on the Appointments Clause of the Constitution, Article II, Section 2, Clause 2. Under that provision, so-called principal officers of the United States must be nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate under its “Advice and Consent” powers.

He argued that Mr. Mueller was a principal officer because he is exercising significant law enforcement authority and that since he has not been confirmed by the Senate, his appointment was unconstitutional. As one of us argued at the time, he was wrong. What makes an officer a principal officer is that he or she reports only to the president.

While it may be true (as Conway argued at the link) that Calabresi’s arguments are wrong for Mueller, if they’re right for Mueller, then they’re all the more true for Whitaker. So if Mueller should have been Senate confirmed, then Whitaker more obviously would need to be.

John Kelly’s involvement may (and I suspect does) present added conflicts

Then there’s John Kelly’s role, as someone who had a key role in the firing but whose testimony Mueller is currently pursuing (possibly via subpoena).

Kelly is among the people about whom there is the most active dispute legal between the Special Counsel and the White House, a fight picked by the legally competent Emmet Flood.

And Kelly was the person who forced Jeff Sessions to resign on Wednesday. As far as is public (and there’s surely a great deal that we have yet to learn about who was in the decision to force Sessions to resign and when that happened and who dictated the form it would take).

But Kelly had the key role of conveying the President’s intent, in whatever form that intent was documented, to Sessions. If Trump’s past firings are any precedent, Kelly had a very big role in deciding how it would happen.

So the guy whose testimony Mueller may be most actively pursuing (indeed, one who might even be in a legal dispute with), effectuated a plan to undercut Mueller’s plans going forward.

CNN provides more context for Kelly’s role, showing him to be involved in the last attempt to install Whitaker and suggesting that Kelly consulted Trump before refusing Sessions’ request to stay through the week.

John Kelly, the White House chief of staff, asked Sessions to submit his resignation, according to multiple sources briefed on the call. Sessions agreed to comply, but he wanted a few more days before the resignation would become effective. Kelly said he’d consult the President.

[snip]

Rosenstein and [PDAAG Ed] O’Callaghan, the highest-ranked officials handling day-to-day oversight of Mueller’s investigation, urged Sessions to delay the effective date of his resignation.

Soon, Whitaker strode into Sessions’ office and asked to speak one-on-one to the attorney general; the others left the two men alone. It was a brief conversation. Shortly after, Sessions told his huddle that his resignation would be effective that day.

O’Callaghan had tried to appeal to Sessions, noting that he hadn’t heard back about whether the President would allow a delay. At least one Justice official in the room mentioned that there would be legal questions about whether Whitaker’s appointment as acting attorney general is constitutional. Someone also reminded Sessions that the last time Whitaker played a role in a purported resignation — a few weeks earlier in September, with Rosenstein — the plan collapsed.

Sessions never heard in person from the President — the man who gained television fame for his catch-phrase “You’re fired” doesn’t actually like such confrontation and prefers to have others do the firing, people close to the President say. Kelly called Sessions a second time to tell him the President had rejected his request for a delay.

Nevertheless, a guy Mueller is trying to interview was right there in the loop, making two efforts to install someone whose sole apparent job is to undercut Mueller.

Everything Whitaker touches may turn to shit

Now, maybe Flood would still have bought off on this — though the multiple reports now claim no one at the White House knew about Whitaker’s problems suggest he may not have been in the vetting loop (because, again, he’s competent and knows the import of vetting).

But there’s one more thing to account for. Everything Whitaker touches may turn to legal shit. It’s a point Katyal and Conway make.

President Trump’s installation of Matthew Whitaker as acting attorney general of the United States after forcing the resignation of Jeff Sessions is unconstitutional. It’s illegal. And it means that anything Mr. Whitaker does, or tries to do, in that position is invalid.

This appointment could embroil DOJ in legal challenges for years, at least, as plaintiffs and defendants claim that DOJ took some action against them that can only be authorized by a legal Attorney General.

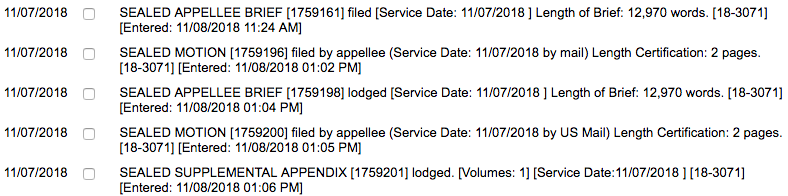

While I don’t think it’s likely, it’s possible that’s the point. As I noted earlier, on Thursday Mueller’s team seemed to be staking a claim that they can continue to operate as they have been.

But their authority, or at least Mueller’s and the others who aren’t AUSAs temporarily reassigned to Mueller, all stems from a legally valid Attorney General or Acting one. If Mueller continues to operate while the legally problematic Whitaker claims to authorize them, what does that do for their actions?

That may be why the DC Circuit wants more (public) briefing on this question in the Andrew Miller case. By appointing a totally inappropriate AG, Trump might just be pursuing his longterm strategy of chaos.

Is this Don McGahn’s last fuck-up?

This entire post is premised on two things: first, that Emmet Flood is among the rare people in Trump’s orbit who is very competent. It also assumes that because both these issues — White House Counsel until Cipollone takes over, and White House Counsel in charge of protecting Trump from the Mueller investigation — would fall solidly in Flood’s portfolios, he would have a significant role in the plot.

Perhaps not. Federalist Society’s Leonard Leo is claiming (in a CNN report that should be read in its entirety) he worked on the plan with Don McGahn.

Leonard Leo, the influential executive vice president of the Federalist Society, recommended to then-White House counsel Don McGahn that Whitaker would make a good chief of staff for Sessions.

“I recommended him and was very supportive of him for chief of staff for very specific reasons,” Leo said Friday.

So maybe this scheme was, instead, planned out by Don McGahn (who has been officially gone since October 17).

But that would raise questions of its own — notably, why this plan was on ice for so long. And why Flood wasn’t in the loop (and why the White House continues to neglect the most basic vetting of people they put in charge of huge parts of our government).

I expect basic competence out of Emmet Flood. But this whole scheme could only be judged competent if the point was to totally discredit anything DOJ does, including but not limited to the Mueller probe.