It seems like the whole world has decided to measure Trump’s conspiracy with Russia not from the available evidence, but based on whether the Steele dossier correctly predicted all the incriminating evidence we now have before us.

The trend started with NPR. According to them (or, at least, NPR’s Phillip Ewing doing a summary without first getting command of the facts), if Michael Cohen didn’t coordinate a Tower-for-sanctions-relief deal from Prague, then such a deal didn’t happen. That’s the logic of a column dismissing the implications of the recent Cohen allocution showing that when Don Jr took a meeting offering dirt on Hillary as “part of Russia and its government’s support for Mr. Trump,” he knew his family stood to make hundreds of millions if they stayed on Vladimir Putin’s good side.

Item: Cohen ostensibly played a key role in the version of events told by the infamous, partly unverified Russia dossier. He denied that strongly to Congress. He also has admitted lying to Congress and submitted an important new version of other events.

But that new story didn’t include a trip to Prague, as described in the dossier. Nor did Cohen discuss that in his interview on Friday on ABC News. Could the trip, or a trip, still be substantiated? Yes, maybe — but if it happened, would a man go to prison for three years without anyone having mentioned it?

As I noted, Mueller laid out the following in the unredacted summary of Cohen’s cooperation.

Consider this passage in the Mueller Cohen sentencing memo.

The defendant’s false statements obscured the fact that the Moscow Project was a lucrative business opportunity that sought, and likely required, the assistance of the Russian government. If the project was completed, the Company could have received hundreds of millions of dollars from Russian sources in licensing fees and other revenues. The fact that Cohen continued to work on the project and discuss it with Individual 1 well into the campaign was material to the ongoing congressional and SCO investigations, particularly because it occurred at a time of sustained efforts by the Russian government to interfere with the U.S. presidential election. Similarly, it was material that Cohen, during the campaign, had a substantive telephone call about the project with an assistant to the press secretary for the President of Russia.

Cohen’s lies, aside from attempting to short circuit the parallel Russian investigations, hid the following facts:

- Trump Organization stood to earn “hundreds of millions of dollars from Russian sources” if the Trump Tower deal went through.

- Cohen’s work on the deal continued “well into the campaign” even as the Russian government made “sustained efforts … to interfere in the U.S. presidential election.”

- The project “likely required[] the assistance of the Russian government.”

- “Cohen [during May 2016] had a substantive telephone call about the project with an assistant to the press secretary for the President of Russia [Dmitri Peskov].”

But because the new Cohen details (along with the fact that he booked tickets for St. Petersburg the day of the June 9 meeting, only to cancel after the Russian hack of the DNC became public) didn’t happen in Prague, it’s proof, according to NPR, that there is no collusion. [Note, NPR has revised this lead and added an editors note labeling this piece as analysis, not news.]

Political and legal danger for President Trump may be sharpening by the day, but the case that his campaign might have conspired with the Russian attack on the 2016 election looks weaker than ever.

There are other errors in the piece. It claims “Manafort’s lawyers say he gave the government valuable information,” but they actually claimed he didn’t lie (and it doesn’t note that the two sides may have gone back to the drawing board after that public claim). Moreover, the column seems to entirely misunderstand that Manafort’s plea (would have) excused him from the crimes in chief, which is why they weren’t charged. Nor does it acknowledge the details from prosecutors list of lies that implicate alleged GRU associate Konstantin Kilimnik in an ongoing role throughout Trump’s campaign.

Then there’s the NPR complaint that Mike Flynn, after a year of cooperation, is likely to get no prison time. It uses that to debunk a straw man that Flynn was a Russian foreign agent.

Does that sound like the attitude they would take with someone who had been serving as a Russian factotum and who had been serving as a foreign agent from inside the White House as national security adviser, steps away from the Oval Office?

That’s never been the claim (though the Russians sure seemed like they were cultivating it). Rather, the claim was that Flynn hid details of Trump’s plans to ease sanctions, an easing of sanctions Russians had asked Don Jr to do six months earlier in a meeting when they offered him dirt. The 302 from his FBI interview released last night makes it clear that indeed he did.

Finally, NPR is sad that Carter Page hasn’t been charged.

Will the feds ever charge Trump’s sometime foreign policy adviser, Carter Page, whom they called a Russian agent in the partly declassified application they made to surveil him?

This is not a checklist, where Trump will be implicated in a conspiracy only if the hapless Page is indicted (any case against whom has likely been spoiled anyway given all the leaking). The question, instead, is whether Trump and his spawn and campaign manager and longtime political advisor (the piece names neither Don Jr nor Roger Stone, both of whom have been saying they’ll be indicted) entered into a conspiracy with Russians.

In short, this piece aims to measure whether there was “collusion” not by looking at the evidence, but by looking instead at the Steele dossier to see if it’s a mirror of the known facts.

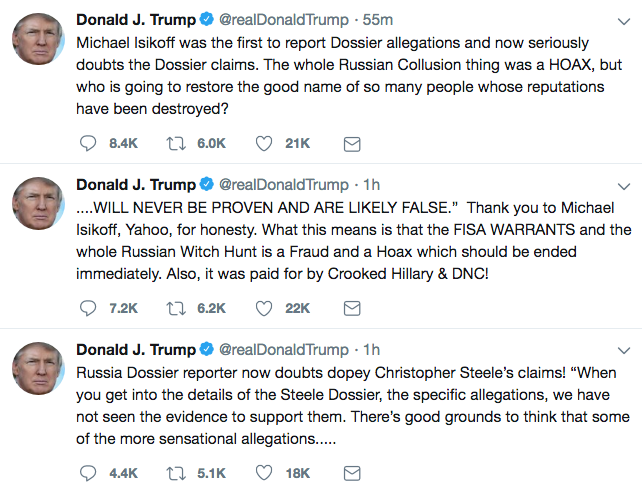

But NPR isn’t the only outlet measuring reality by how it matches up to the Steele dossier. This piece describes that Michael Isikoff thinks, “All the signs to me are, Mueller is reaching his end game, and we may see less than what many people want him to find,” in part because of the same three points made in the NPR piece (Cohen didn’t go to Prague, no pee tape has been released, and Flynn will get no prison time), but also because Maria Butina — whose investigation was not tied to the Trump one, but whom Isikoff himself had claimed might be — will mostly implicate her former boyfriend, Paul Erickson. In the interview, Isikoff notes that because the dossier has not been corroborated, calling it a “mixed record, at best … most of the specific allegations have not been borne out” and notes his own past predictions have not been fulfilled. Perhaps Isikoff’s reliance on the dossier arises from his own central role in it, but Isikoff misstates some of what has come out in legal filings to back his claim that less will come of the Mueller investigation than he thought.

Then there is Chuck Ross. Like Isikoff, Ross has invested much of his investigative focus into the dossier, and thus is no better able than Isikoff to see a reality but for the false mirror of the dossier. His tweet linking a story laying out more evidence that Michael Cohen did not go to Prague claims that that news is “a huge blow for the collusion narrative.”

Even when Ross wrote a post pretending to assess whether the Michael Cohen plea allocution shows “collusion,” Ross ultimately fell back on assessing whether the documents instead proved the dossier was true.

Notably absent from the Mueller filing is any indication that Cohen provided information that matches the allegations laid out in the Steele dossier, the infamous document that Democrats tout as the roadmap to collusion between the Trump campaign and Russian government.

The most prominent allegation against Cohen in the 35-page report is that he traveled to Prague in August 2016 to meet with Kremlin insiders to discuss paying off hackers who stole Democrats’ emails.

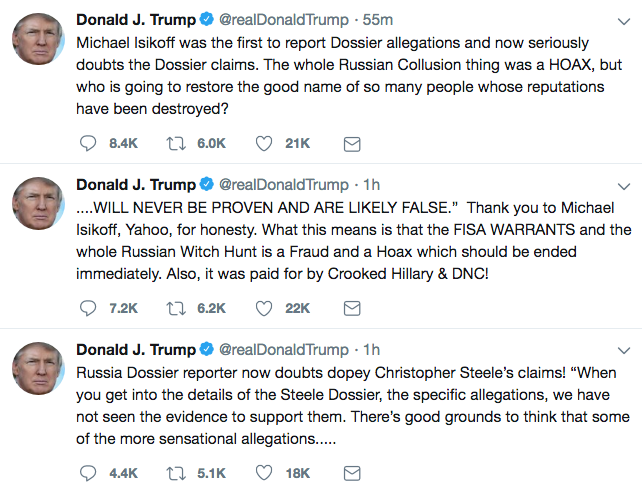

The Isikoff comments appear to have traveled via Ross to Trump’s Twitter thumbs, all without assessing the evidence in plain sight.

Meanwhile, Lawfare is erring in a parallel direction, checking on the dossier to see “whether information made public as a result of the Mueller investigation—and the passage of two years—has tended to buttress or diminish the crux of Steele’s original reporting.”

Such an exercise is worthwhile, if conducted as a measure of whether Christopher Steele obtained accurate intelligence before it otherwise got reported by credible, public sources. But much of what Lawfare does does the opposite — assessing reports (it even gets the number of reports wrong, saying there are 16, not 17, which might be excusable if precisely that issue hadn’t been the subject of litigation) out of context of when they were published. Even still, aside from Steele’s reports on stuff that was already public (Carter Page’s trip to Moscow, Viktor Yanukovych’s close ties to Paul Manafort), the post reaches one after another conclusion that the dossier actually hasn’t been confirmed.

There’s the 8-year conspiracy of cooperation, including Trump providing Russia intelligence. [my emphasis throughout here]

Most significantly, the dossier reports a “well-developed conspiracy of co-operation between [Trump and his associates] and the Russian leadership,” including an “intelligence exchange [that] had been running between them for at least 8 years.” There has been significant investigative reporting about long-standing connections between Trump, his associates and Kremlin-affiliated individuals, and Trump himself acknowledged that the purpose of a June 2016 meeting between his son, Donald Trump Jr. and a Kremlin-connected lawyer was to obtain “dirt” on Hillary Clinton. But there is, at present, no evidence in the official record that confirms other direct ties or their relevance to the 2016 presidential campaign.

There’s the knowing support for the hack-and-leak among Trump and his top lackeys.

It does not, however, corroborate the statement in the dossier that the Russian intelligence “operation had been conducted with the full knowledge and support of Trump and senior members of his campaign team.”

There’s Cohen’s Trump Tower deal.

These documents relate to Cohen’s false statements to Congress regarding attempted Trump Organization business dealings in Russia. The details buttress Steele’s reporting to some extent, but mostly run parallel, neither corroborating nor disproving information in the dossier.

There’s Cohen’s role in the hack-and-leak, including his trip to Prague.

Even with the additional detail from the Cohen documents, certain core allegations in the dossier related to Cohen—which, if true, would be of utmost relevance to Mueller’s investigation—remain largely unconfirmed, at least from the unredacted material. Specifically, the dossier reports that there was well-established, continuing cooperation between the Trump campaign and the Kremlin; that Cohen played a central role in the coordination of joint efforts; and that he traveled to Prague to meet with Russian officials and cut-outs.

There’s Papadopoulos, who (as Lawfare admits) doesn’t show up in the dossier; here they argue he could have, without asking why Steele missed him running around London talking to people who traveled in Steele’s circles.

We revisit his case because it resonates with one of the themes of the dossier, which is the extensive Russian outreach effort to an array of individuals connected to the Trump campaign. Steele’s sources reported on alleged interactions between Carter Page and Russian officials, but Papadopoulos’s conduct would have fit right in.

Again, except for the stuff that was publicly known, Lawfare assesses one after another claim from the dossier and finds that Mueller’s investigation has not corroborated the specific claims, even while Mueller has provided ample evidence of something else going on. But that doesn’t stop Lawfare from claiming that Mueller has “confirm[ed] pieces of the dossier.”

The Mueller investigation has clearly produced public records that confirm pieces of the dossier. And even where the details are not exact, the general thrust of Steele’s reporting seems credible in light of what we now know about extensive contacts between numerous individuals associated with the Trump campaign and Russian government officials.

However, there is also a good deal in the dossier that has not been corroborated in the official record and perhaps never will be—whether because it’s untrue, unimportant or too sensitive. As a raw intelligence document, the Steele dossier, we believe, holds up well so far. But surely there is more to come from Mueller’s team. We will return to it as the public record develops.

In the end, I actually think Mueller may show that Trump, Stone, and Manafort did abet the hack-and-leak campaign, certainly the later parts of it, and that the Trump Tower deal was a key part of the quid pro quo. That’s aside from anything that Trump did with analytics data made available, if it was. But Mueller has just shown the outlines of where a case in chief might fit thus far. And where has has, those outlines raise one after another question of why Steele missed evidence (like the June 9 meeting) that was literally sitting in front of him. No one is answering those questions in these retrospectives.

One reason this effort, coming from Lawfare, is particularly unfortunate is because of a detail recently disclosed in Comey’s recent testimony to Congress. As you read, remember that this exchange involves Mark Meadows, who is the source of many of the most misleading allegations pertaining to the Russian investigation. In Comey’s first appearance this month (given Comey’s comments after testifying yesterday, I expect we’ll see more of the same today when his transcript is released), Meadows seemed to make much of the fact that Michael Sussman, who works with Marc Elias at Perkins Coie, provided information directly to Lawfare contributor James Baker.

Mr. Meadows. So are you saying that James Baker, your general counsel, who received direct information from Perkins Coie, did so and conveyed that to your team without your knowledge?

Mr. Comey. I don’t know.

Mr. Meadows. What do you mean you don’t know? I mean, did he tell you or not?

Mr. Comey. Oh, I — well —

Mr. Meadows. James Baker, we have testimony that would indicate that he received information directly from Perkins Coie; he had knowledge that they were representing the Democrat National Committee and, indeed, collected that information and conveyed it to the investigative team. Did he tell you that he received that information from them? And I can give you a name if you want to know who he received it from.

Mr. Comey. I don’t remember the name Perkins Coie at all.

Mr. Meadows. What about Michael Sussmann?

Mr. Comey. I think I’ve read that name since then. I don’t remember learning that name when I was FBI Director. I was going to ask you a followup, though. When you say “that information,” what do you mean?

Mr. Meadows. Well, it was cyber information as it relates to the investigation.

Mr. Comey. Yeah, I have some recollection of Baker interacting with — you said the DNC, which sparked my recollection — with the DNC about our effort to get information about the Russian hack of them —

Mr. Meadows. Yeah, that’s — that’s not — that’s not what I’m referring to.

Mr. Comey. — but I don’t — I don’t remember anything beyond that.

Mr. Meadows. And so I can give you something so that you — your counsel can look at it and refresh your memory, perhaps, as we look at that, but I guess my concern is your earlier testimony acted like this was news to you that Perkins Coie represented the Democratic National Committee, and yet your general counsel not only knew that but received information from them that was transmitted to other people in the investigative team. [my emphasis]

I have long wondered how the Perkins Coie meeting with the FBI on the hack timed up with the hiring, by Fusion GPS working for Perkins Coie, of Christopher Steele lined up, and that appears to be where Meadows is going to make his final, desperate stand. An earlier version of this hoax revealed that it pertained to materials on hacking, but did not specify that Steele had anything to do with it (indeed, Steele was always behind public reporting on the hack-and-leak).

Still, it would be of more public utility for Lawfare to clarify this detail than engage in yet another exercise in rehabilitating the dossier.

Instead, they — just like everyone else choosing not to look for evidence (or lack thereof) in the actual evidence before us — instead look back to see whether Steele’s dossier was a mirror of reality or something else entirely. If it’s the latter — and it increasingly looks like it is — then it’s time to figure out how and what it is.

Update: Cheryl Rofer did a line by line assessment of Steele’s dossier which is worthwhile. I would dispute a number of her claims (and insist that Steele’s reporting on the hacks be read in the temporal context in which he always lagged public reporting) and wish she’d note where the public record shows facts that actually conflict with the dosser. But it is a decent read.

As I disclosed in July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.