One Man’s Flourish Is Another Man’s Seditious Conspiracy: DOJ’s Typo and the Brandon Straka Plea Deal

The government released their sentencing memo for Brandon Straka yesterday. It confirms that the propagandist got a ridiculously light plea deal because he “cooperated” with the government. But, particularly because of what must be a typo in the government filing, it raises more questions about the fairness of the prosecution for the first purveyor of the Big Lie to be sentenced in January 6 than it provides answers.

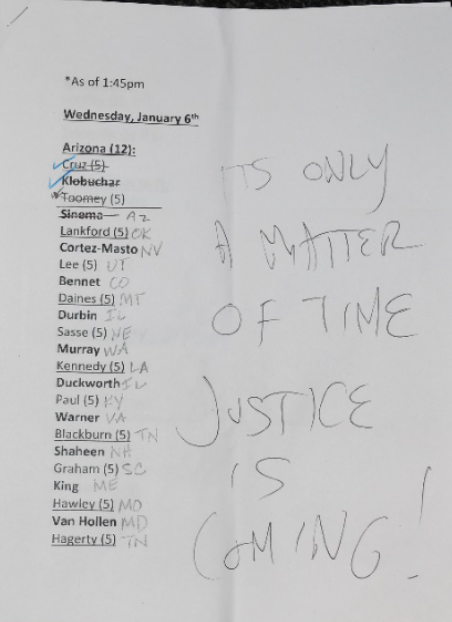

As I’ve laid out repeatedly, Straka was a speaker on January 5 and was slated to speak again on January 6 at one of the rallies that provided the excuse to bring more bodies to the Capitol. He also played a central role in riling up a mob at Michigan’s vote count at TCF Center in November 2020. In other words, he was instrumental in the effort to sow violence by leading people to believe false claims about the election.

As described in the sentencing memo, that’s precisely what Straka did at the East side of the Capitol, too.

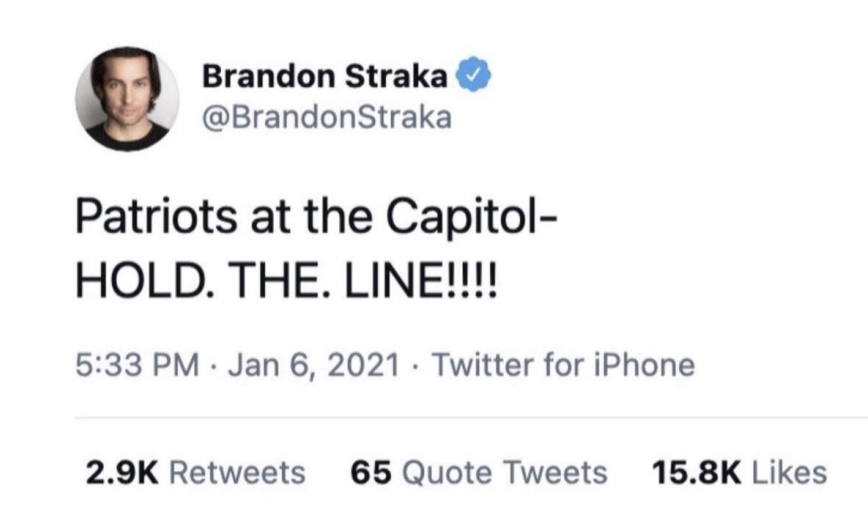

Straka pleaded guilty to one count of 40 U.S.C. § 5104(e)(2)(D), Disorderly Conduct in the Capitol Grounds. As explained herein, a four-month home detention sentence is appropriate in this case because: (1) the defendant has a significant public profile, which he utilized to promote his activity on January 6, (2) the defendant learned of the breach of the U.S. Capitol Building and went to join the rioters; (3) upon arriving at the U.S. Capitol, the defendant encouraged others to storm the U.S. Capitol; (4) the defendant recorded video of the rioters entering the U.S. Capitol; (5) the defendant encouraged rioters to take an officer’s protective shield from the officer’s possession, and (6) the defendant took to social media and encouraged rioters who remained at the U.S. Capitol to “hold the line” even after he had left Capitol grounds on January 6.

[snip]

Here, Straka’s participation in a riot that actually succeeded in halting the Congressional certification combined with his celebration and endorsement of the unauthorized entry of the U.S. Capitol and violent conduct of the rioters to his hundreds of thousands of followers, his act of encouraging rioters to take a U.S. Capitol Police officer’s shield, and the need for deterrence renders a four-month home detention sentence both necessary and appropriate in this case.

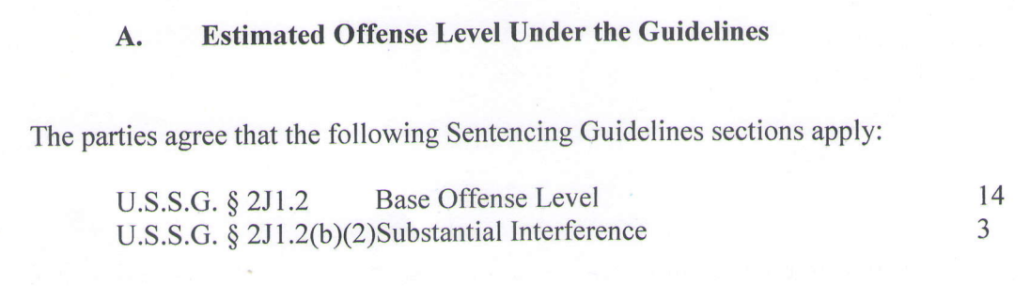

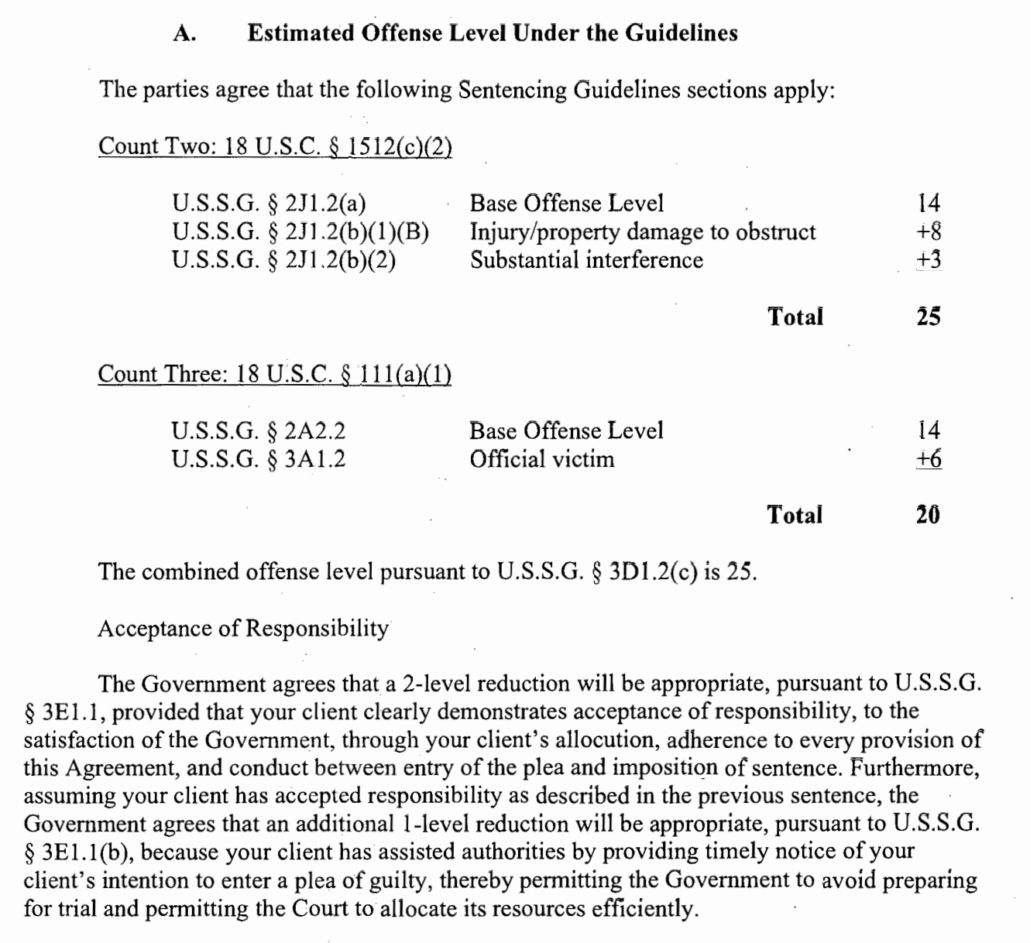

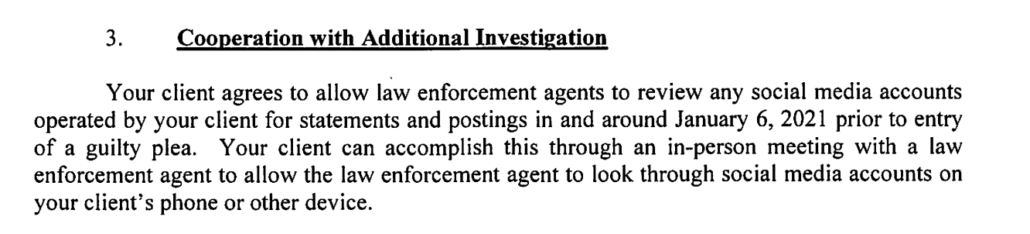

Straka was originally charged with civil disorder and trespassing, but not the obstruction of the vote count that he was clearly part of. In October, he got a plea deal to plead only to the lesser of the two trespassing statutes, eliminating a felony civil disorder charge. As I previously noted, his plea agreement included the standard cooperation paragraph that usually suggests someone has not yet cooperated.

But DOJ, in their sentencing memo, claims he did, and even included a sealed filing describing the substance of the cooperation, as they would in support of a 5.1K letter that more formalized cooperators get.

7 The government will supplement this filing with a sealed addendum that will provide this Court with information related to Brandon Straka’s interviews.

But even the memo’s description of Straka’s initial “cooperative” interviews, the ones he did before getting that sweet plea deal, make it clear that, at least at the beginning, he was bullshitting them.

Straka was arrested on January 25, 2021. Straka voluntarily agreed to be interviewed by FBI. Straka’s initial interview occurred on February 17, 2021. Straka recounted what occurred on January 6. Straka denied seeing any police officers as he walked to the U.S. Capitol. He also denied seeing any barriers or signage indicating that the U.S. Capitol was closed. Straka denied removing the posts out of fear of getting arrested. Instead, he explained that he removed the videos because he felt “ashamed.” He denied knowing that people were “attacking, hurting, and killing people.”

Straka described seeing people “clustered” and “packed in” near the entrance to the U.S. Capitol. He admitted to video recording the event and later posting and removing the videos from Twitter. He also admitted knowing that the rioters were entering the U.S. Capitol without authorization and with the intent to interfere with Congress. Straka provided additional information to the FBI regarding the events leading up to and during January 6. After this initial interview, the FBI met with Straka a second time on March 25, 2021 with follow-up questions. Straka was cooperative during the interviews.

Indeed, later parts of the memorandum debunk claims Straka made in that interview, completely undermining the description of these as cooperative interviews.

Straka stood at the entrance of the East Rotunda Doors as rioters attempted to enter despite the presence of officers near the door. Alarms from inside the U.S. Capitol can be heard in the background as Straka approaches the doorway’s entrance: a loud, high-pitched, continuous beeping, similar to a smoke alarm. If Straka was unaware that his and the rioters’ presence was not authorized, he should have known it when he heard the sound of the alarms. Additionally, as Straka approached the doorway, he was met by the smell of tear gas that had been deployed by officers inside of the U.S. Capitol.

The memorandum also clearly shows that any remorse Straka has expressed was self-serving.

Straka has indicated that his decision to attend the U.S. Capitol breach was “stupid and a tragic decision.” In his interview with FBI, Straka stated that he did not know that violence and death would occur that day. He then expressed shame for participating in the event. Yet, it is worth pointing out that Straka believes that “the consequences for his actions this far have been quite extreme and disproportionate given his involvement.” Straka also believes that he is misunderstood. He has also expressed concern about how his business has been affected. ECF 28 ¶¶ 23-25. These statements indicate that Straka does not understand the gravamen of his conduct and that of the rioters on January 6.

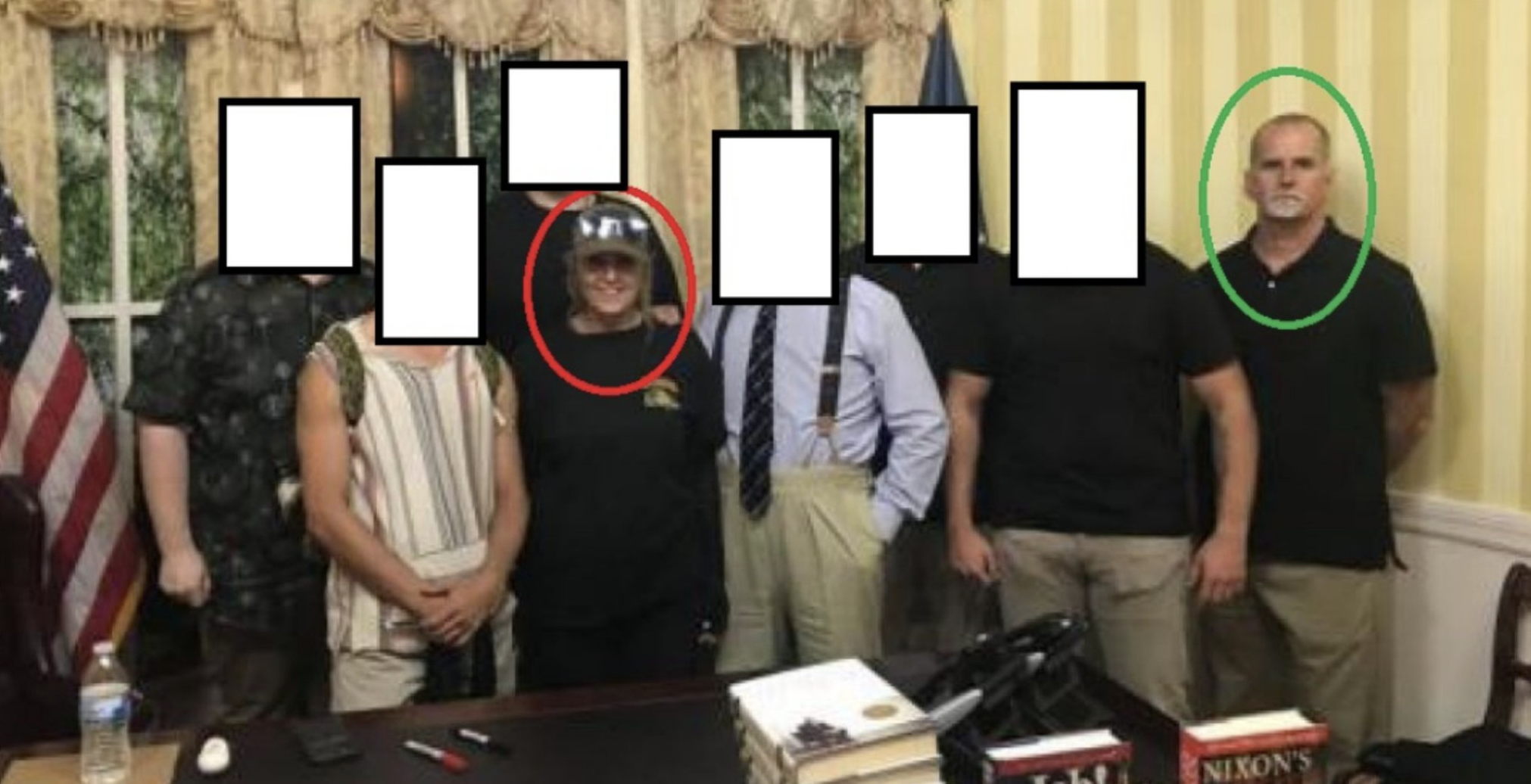

And the memorandum obscures the chronology of Straka’s actions from the day and relies on his word for at least one key detail which the FBI could have (and did, for other insurrectionists) confirmed via more investigation. Straka went to Trump’s speech at the Ellipse. Videos show that he left the speech with Mike Flynn just as the speech was ending, walking unimpeded through the VIP section. Straka claims he took the Metro to the Capitol and arrived between 2 and 2:20, which given that everybody else was walking, is likely only possible if he killed a half hour somewhere before hopping the Metro, presumably getting on at Metro Center or Federal Triangle and getting off at Capitol South. That detail is critical, because it’s how Straka sustains a claim that:

- He only learned of the assault on the Capitol as he was already traveling over there and not before

- He arrived at the Capitol between the time he learned of the assault and when his speech was canceled (2:00 to 2:20)

- He learned his speech was canceled at 2:33

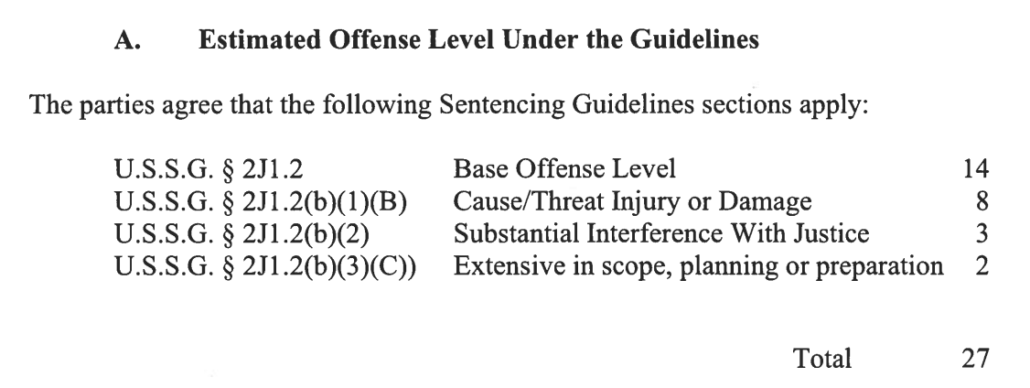

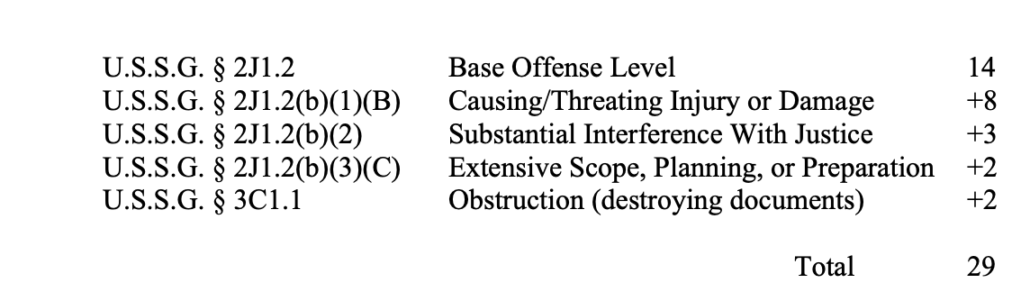

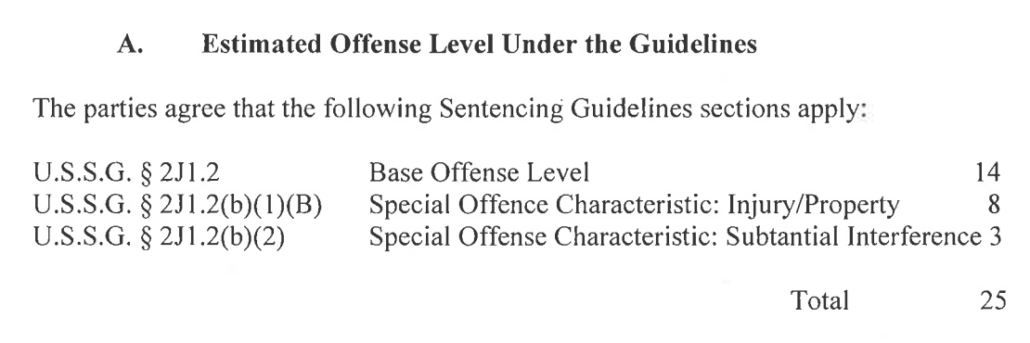

Here’s how it looks in the sentencing memorandum, separated by several pages.

The next day, January 6, 2021, Straka attended the “Rally to Save America” on the White House Ellipse and then planned to travel to an area near the U.S. Capitol Building where he was going to give another speech. See ECF 1, p. 2 at ¶ 3 Straka used the Metro to travel to the U.S. Capitol. Id. While traveling to the U.S. Capitol, he received alerts on his telephone stating that former Vice President Mike Pence was “not going to object to certifying Joe Biden.” Id. Straka continued to make his way to the U.S. Capitol. Id. While walking, Straka learned that the U.S. Capitol had been breached. Id. Straka estimated that he got off of the Metro sometime between 2:00 p.m. and 2:20 p.m. before making his way to the U.S. Capitol grounds. See ECF 28, at ¶ 18.

[snip]

At 2:33 pm on January 6, 2021, Michael Coudrey, the national coordinator for Stop the Steal, sent a message to a group chat telling those in the chat that the event that Straka was scheduled to speak at would be delayed because “They stormed the capital[sic].” Joshua Kaplan and Joaquin Sapien, New Details Suggest Sernior Trump Aides Knew Jan. 6 Rally Could Get Chaotic, ProPublica (June 25, 2021) available at https://www.propublica.org/article

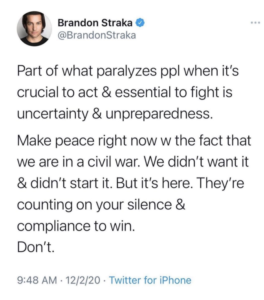

/new-detailssuggest-senior-trump-aides-knew-jan-6-rally-could-get-chaotic (last visited December 16, 2021). Straka responded, “I just got gassed! Never felt so fucking alive in my life!!!” Id. Later, as law enforcement was still working to clear rioters from Capitol grounds, Straka encouraged them to continue fighting:

It’s still totally inexplicable. Even if Straka didn’t have knowledge he was traveling into an active riot in advance (a really sketchy claim), he still marched right up the steps of the East side of the Capitol encouraging violent entry, and then stuck around for hours encouraging rioters to keep going. DOJ could have checked the timing of his story by — as they did with other Jan 6 defendants — checking for Metro card purchases, swipes, or surveillance video in the Metro. Instead, they seem to have taken his word for the chronology.

Thus far, then, it looks like Straka successfully bullshitted DOJ for a sweet plea deal.

That treatment is all the more problematic given the discomfort regarding Straka’s incitement in different places in the sentencing memo. In describing his January 5 speech at the Stop the Steal rally, DOJ dismissed his call to “revolution” as “flourishes.”

During his five-minute long speech, Straka again used common rhetorical flourishes, referring to the rally attendees as “patriots,” and referenced a “revolution” multiple times. Id. at 32:27-37:18 Straka directed the attendees to “fight back.” Id.

But in the sentencing memo, DOJ called the same kind of speech on social media before that, often on key days in the developing conspiracy, speech that “could reasonably have been interpreted by some readers as a call for more than just a figurative struggle.”

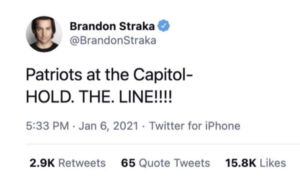

Following the election, Straka stoked the passions of his followers, frequently telling the “Patriots” that it was time to “rise up” as part of a “civil war.” Many of these messages contain rhetorical flourishes that are common in political speech. However, some of Straka’s references to concrete planning and action could reasonably have been interpreted by some readers as a call for more than just a figurative struggle. In early December 2020, Straka sent out messages informing them that they “could not allow” a presidential transition and encouraging his followers to prepare for a civil war

That is, DOJ admits in its sentencing memo that Straka was stoking violence during the entire transition period.

Thus it happened that, on the very same day DOJ rolled out a seditious conspiracy indictment against Stewart Rhodes for, in part, warning on November 5, “we aren’t getting through this without a civil war,” and then warning on December 11 that if Joe Biden were to assume the Presidency, “it will be a bloody and desperate fight,” DOJ made a case that a guy who, in the same weeks, was also calling for civil war, should get just home confinement.

To be sure, there’s no evidence Straka engaged in military training or purchased weapons. But if Stewie’s incitement counts as sedition, then surely Straka’s counts as obstruction of the peaceful transfer of power.

Which brings us back to DOJ’s claims about Straka’s cooperation and that sealed addendum. According to the memo, as written, Straka had three interviews: one on February 17, 2021, another on March 25, 2021, and a third on — it claims — January 5, 2022.

On January 5, 2022, Straka met with prosecutors from the United States Attorney’s Office and the FBI a third time. The purpose of the interview was for the government to ask Straka follo-up [sic] questions. Consistent with his previous interviews, Straka was cooperative. The interviews were conducted in anticipation of the plea agreement that defendant would later enter.7

Except that makes no sense. He signed his statement of offense on September 14, 2021 and pled guilty in October. A January 5, 2022 interview couldn’t have “anticipat[ed] the plea agreement” he entered three months earlier. [Update: I’ve gotten clarification that the reference “the interviews” was meant to refer to the series of interviews. It still doesn’t make sense, but may reflect a late-date addition without correction of the antecedent.]

Moreover, DOJ offers no public explanation for details in this motion for a continuance, which the government attempted to seal after the fact, an attempt Judge Dabney Friedrich refused. It reveals that Straka told the government something new in December, and also that something unexpected came up in the Presentence report.

On December 8, 2021, the defendant provided counsel for the government with information that may impact the government’s sentencing recommendation. Additionally, the government is requesting additional time to investigate information provided in the Final PreSentence Report. Because the government’s sentencing recommendation may be impacted based on the newly discovered information, the government and defendant request a 30-day continuance of this case so that the information can be properly evaluated.

Given the timing of that continuance, it might explain a third meeting with Straka on January 5 — nine days ago. But that would suggest that the information wasn’t provided before Straka got this sweet plea deal.

There are any of a number of things going on. Perhaps it’s true that Straka provided useful information early in the investigation and in consideration for that got a sweet plea deal, as happened with Jacob Riles. Perhaps it’s true that Straka was more honest in those early interviews than portrayed in this memorandum.

Or, as seems more likely given the record and the rhetorical contortions AUSA Brittany Reed made in this sentencing memo, FBI let Straka bullshit them and based on that, he scored a ridiculous plea deal, and only after that, his presentence report disclosed things that FBI should have found last spring.

It may be that the belated discovery in December, in the end, makes the plea deal worth it. If Straka is willing to share honest details of how months of incitement led up to that attempted breach on the East steps; if Straka has provided details of what Mike Flynn was up to after Trump’s speech; if Straka belatedly confessed that there was a concerted plan to converge on the top of the East steps, then Straka’s preferential treatment may be worth it.

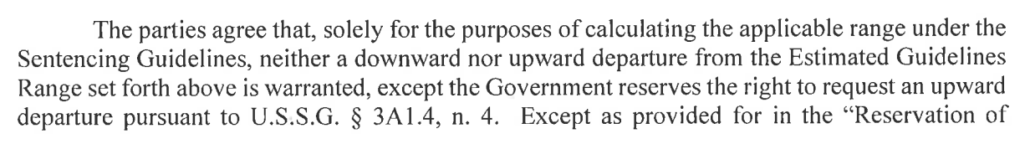

But DOJ really needs to provide more transparency on what went down, one that doesn’t include an obvious typo obscuring the timeline. If Paul Hodgkins has to serve eight months for obstruction because he wandered onto the Senate of floor and Jenny Cudd only got to plead from obstruction down to the more serious trespassing charge because she repeated the calls for civil war that people like Straka were making on January 5, then equity demands a far better explanation for Straka’s preferential treatment here.

As noted, Straka’s is the first sentencing for one of the organizer-inciters who will need to be held to account if DOJ wants to really pursue the people who master-minded this insurrection. If FBI screwed up (or tried to protect Straka), then DOJ needs to come clean on that and make it clear how they’ll avoid such problems in the future.

Presenting two inexplicable timelines is not the way to do that.

Update: Fixed reference to presentence report. And included clarification regarding “typo.”