Former Surveillance Lawyer Peter Keisler Pushes for Surveillance Limits

I’ve been laying low so supporters of USA Freedom can try to get a vote for cloture allowing debate for their bill in the Senate (and also trying to duck getting back into the arguments I made about Jonathan Gruber in 2009 and 2010). I’ve had my say on the former issue here and here.

I’ve been laying low so supporters of USA Freedom can try to get a vote for cloture allowing debate for their bill in the Senate (and also trying to duck getting back into the arguments I made about Jonathan Gruber in 2009 and 2010). I’ve had my say on the former issue here and here.

But even as USA Freedom faces an uncertain future in the Senate, something interesting happened in the 11th Circuit.

I wrote in June about the 11th Circuit decision in US v. Quartavious Davis. In a decision written by David Sentelle (on loan from the DC Circuit) the Circuit overturned a conviction based almost entirely on stored cell site location information (CSLI).

The government filed for rehearing en banc which was granted.

AT&T just submitted an amicus brief generally supporting a higher standard for CSLI.

This is no hippie brief. Generally, it calls for more clarity for the providers, and ultimately concludes asking for one standard.

However the scope of the Fourth Amendment’s protection is resolved, a clear and categorical rule will benefit all parties involved in the application of Section 2703(d), including the technology companies subject to orders to produce information. Whatever standard the Court ultimately determines the government must satisfy, the third party records cases may provide an unsatisfactory basis for resolving this case. Smith and Miller rested on the implications of a customer’s knowing, affirmative provision of information to a third party and involved less extensive intrusions on personal privacy. Their rationales apply poorly to how individuals interact with one another and with information using modern digital devices. In particular, nothing in those decisions contemplated, much less required, a legal regime that forces individuals to choose between maintaining their privacy and participating in the emerging social, political, and economic world facilitated by the use of today’s mobile devices or other location based services.

But to support that stance, it argues that because of increasing accuracy, CSLI is probably more intrusive than the car-based GPS tracker found to require a warrant in US v. Jones.

CSLI at times may provide more sensitive and extensive personal information than the car tracking information at issue in Jones. Users typically keep their mobile devices with them during the entire day, potentially providing a much more extensive and continuous record of an individual’s movements and living patterns than that provided by tracking a vehicle; CSLI, therefore, is not limited to the largely public road system or to when the device user is in a vehicle.

More interesting still, it argues that the 3rd Party doctrine doesn’t work anymore.

The privacy and related social interests implicated by the use of modern mobile devices and by CSLI are fundamentally different and more significant than those evaluated in Miller and Smith. Miller, 425 U.S. at 443 (“We must examine the nature of the particular documents sought to be protected in order to determine whether there is a legitimate ‘expectation of privacy’ concerning their contents”); Smith, 442 U.S. at 741-42 (emphasizing the “limited capabilities” of pen registers). Use of mobile devices, as well as other devices or location based services, has become integral to most individuals’ participation in the new digital economy: those devices are a nearly ever-present feature of their most basic social, political, economic, and personal relationships. In recent years, this has become especially true of the data communications – from email and texting to video to social media connections – that occur on a nearly continuous basis whenever mobile devices are

turned on.[snip]

Nor does Miller or Smith address how individuals interact with one another and with different data and media using mobile devices in this digital age. Location enabled services of all types provide a range of information to their users. At the same time, mobile applications, vehicle navigation systems, mobile devices, or wireless services for mobile devices often collect and use data in the background.

As part of that, AT&T talks about CSLI shows interactions.

But perhaps my favorite part of the brief is this:

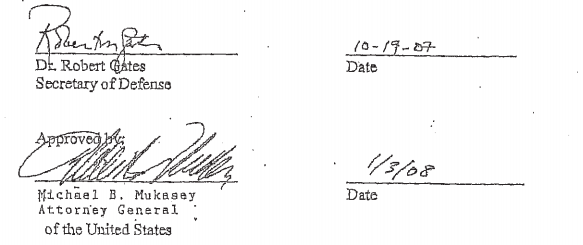

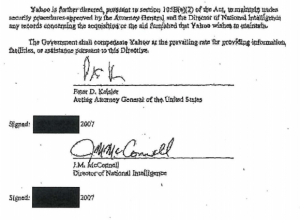

The brief was written by Peter Keisler, a longtime telecom attorney but also — during his brief stint as Acting Attorney General in 2007 — the guy who signed at least Directives (and possibly 2 Certificates) in Protect America Act. See page 34 for where Keisler signed Directives to Yahoo on his last day as Acting AG, November 8, 2007.