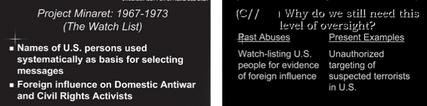

The “Foreign Intelligence” Dragnet May Not Be about “Foreign Intelligence”

There’s one more totally weedy change in the phone dragnet orders I wanted to point out: the flimsy way the program has, over time, tied into “foreign intelligence.”

To follow along, it’s helpful to use the searchable versions of the phone dragnet orders ACLU has posted.

Start by searching on this order — from December 11, 2008, just before FISC started cleaning up the dragnet problems — for “foreign intelligence” (all the earlier orders are, I believe, identical in this respect). You should find 5 instances: 3 references to the FISC, a reference to the language from the Section 215 statute requiring the tangible things be either for foreign intelligence or to protect against international terrorism (¶1 on page 2), and a discussion tying dissemination of US person data to understanding foreign intelligence (¶(3)D on page 9).

In the last instance, the order introduces foreign intelligence, but then drops it. The very next sentence shifts the measure of whether the US person information can be disseminated from “foreign intelligence” to “counterterrorism” — and counterterrorism here is not explicitly tied to international terrorism, although the statute requires it to be.

Before information identifying a U.S. person may be disseminated outside of NSA, a judgment must be made that the identity of the U.S. person is necessary to understand the foreign intelligence information or to assess its importance. Prior to the dissemination of any U.S. person identifying information, the Chief of Information Sharing Services in the Signals Intelligence Directorate must determine that the information identifying the U.S. person is in fact related to counterterrorism information and that it is necessary to understand the counterterrorism information or assess its importance.

Significantly, ¶(3)C on page 8 — the main paragraph restricting NSA’s access to the dragnet data — says nothing about foreign intelligence.

This language would, I believe, have permitted the government to search on and disseminate US person information for reasons without a foreign nexus (and they played word games with other language in the original orders, notably with the word “archives”).

Now check out the next order, dated March 5, 2009. In this — the first of the primary orders dealing with the dragnet problems — the language potentially tying the FBI investigation to foreign intelligence is eliminated (I talked about that change here).The language on dissemination remains the same — that is, the paragraph does not tie dissemination of US person information to terrorism with an international nexus. But ¶(3)C — the key paragraph regulating access — now specifies that NSA can only “query the BR metadata for purposes of obtaining foreign intelligence.”

In the process of very narrowly limiting what NSA could do with the phone dragnet, Judge Reggie Walton added language limiting queries to foreign intelligence purposes, not just terrorism purposes (though I believe it still could be read as permitting dissemination of information without a foreign nexus).

As a reminder, during the interim period, the government had admitted to tracking 3,000 US persons without submitting them to a First Amendment review.

The orders for the following year changed regularly (and the Administration has withheld what are surely the most interesting orders from that year), but they retained that restriction on queries to foreign intelligence purposes.

But now look what that language in ¶(3)C has since evolved into, starting with the order dated October 29, 2010, though the language below comes from the April 25, 2013 order (the October 29 one has “raw data” hand-written into it, making it clear these requirements, including auditability, only applies to the collection store, not the corporate store).

NSA shall access the BR metadata for purposes of obtaining foreign intelligence information only through contact chaining queries of the BR metadata as described in paragraph 17 of the [redacted] Declaration attached to the application as Exhibit A, using selection terms approved as “seeds” pursuant to the RAS approval process described below.5 NSA shall ensure, through adequate and appropriate technical and management controls, that queries of the BR metadata for intelligence analysis purposes will be initiated using only a selection term that has been RAS-approved. Whenever the BR metadata is accessed for foreign intelligence analysis purposes or using foreign intelligence analysis query tools, an auditable record of the activity shall be generated.

At first glance, this paragraph would seem to add protections that weren’t in the orders previously, ensuring that the phone dragnet only be accessed for foreign, not domestic, intelligence.

But it’s actually only partly a protection.

In fact, the “foreign intelligence” language here serves to distinguish this controlled access from the “data integrity” access (though they no longer call it that), which is described in the previous paragraph.

Appropriately trained and authorized tedmical personnel may access the BR metadata to perform those processes needed to make it usable for intelligence analysis. Technical personnel may query the BR metadata using selection terms4 that have not been RAS-approved (described below) for those purposes described above, and may share the results of those queries with other authorized personnel responsible for these purposes, but the results of any such queries will not be used for intelligence analysis purposes. An authorized technician may access the BR metadata to ascertain those identifiers that may be high volume identifiers. The technician may share the results of any such access, i.e., the identifiers and the fact that they are high volume identifiers, with authorized personnel (including those responsible for the identification and defeat of high volume and other unwanted BR metadata from any 9f NSA’ s various metadata repositories), but may not share any other information from the results of that access for intelligence analysis purposes. In addition, authorized technical personnel may access the BR metadata for purposes of obtaining foreign intelligence information pursuant to the requirements of subparagraph (3)C below.

Footnote 4, discussing “selection terms” is a fairly long, entirely redacted paragraph. And the last sentence, allowing these technical personnel to also conduct foreign intelligence information queries, is fairly recent.

This language would seem to describe the data integrity role more than it had previously been, specifying the search for high volume numbers, plus whatever appears in footnote 4. And it would seem to limit the use of such information, since it doesn’t permit “intelligence analysis” (notwithstanding the fact that figuring out which selectors are high volume is intelligence analysis, to say nothing about the underlying technical decisions that shape automated search functions). But the first use of the dragnet in current descriptions pertains not to contact chaining at all, but as a resource for tech personnel to identify certain characteristics of call patterns using raw data.

Further, these tech personnel now get to double dip: access raw data in intelligible form to get it ready for querying and something else, and access it to conduct queries. That they even have that authority — explicitly — ought to raise alarm bells. Anything data integrity analysts see while doing data integrity, they can run as a query to access in a form that can be disseminated.

Now, perhaps this alarming structural issue is not being abused or exploited. Perhaps it shouldn’t concern us that a dragnet purportedly serving “foreign intelligence” purposes seems to serve, even before that, a different role entirely, not only tied to any foreign purpose.

But we have had assurances over and over in the last 8 months that the NSA can only access this database for certain narrowly defined foreign intelligence purposes. That wasn’t, by letter of the order, at least, true for the first three years. And by the letter of the order, it’s not true now.