I Rarely Say I Told You So, Section 704 I Told You So Edition

Since 2014, I have been trying to alert anyone who would listen about Section 704.

That’s a part of FISA Title VII — the part of FISA that will be reauthorized this year. When Congress passed FISA Amendments Act in 2008, they promised they’d protect US persons overseas by requiring an order to surveil them. Almost always, the section that accomplished that was referred to Section 703, which is basically PRISM for Americans overseas.

Except I discovered when I (briefly) worked at the Intercept that NSA never uses 703. Ever. Which meant that what they use to surveil Americans overseas is somewhat looser Section 704 (or, for Americans against whom there is a traditional domestic FISA order, 705b). Except no one — and I mean literally no one, not in the NGO community nor on the Hill — understood how Section 704 was used.

Exactly a year ago, I laid all this out in a post and suggested that, as part of the Section 702 reauthorization this year, Congress should finally figure out how 704 works and whether there are any particular concerns about it.

It turns out, four months before I wrote that, NSA’s Inspector General had finalized a report showing that in the seven and a half years since Section 704 was purportedly protecting Americans overseas, it wasn’t. The report is heavily redacted, but what isn’t redacted showed that the NSA had never set up a means to identify all 704/705b queries, and so couldn’t reliably oversee whether analysts were following the rules. The report showed that Signals Intelligence Compliance and Oversight only started helping DOJ and ODNI do their compliance reviews of 704/705b in October 2014, by providing the queries they could identify to the reviewers. But not all queries can be audited, because not all the feeds in question can be sent to NSA’s auditing and logging system.

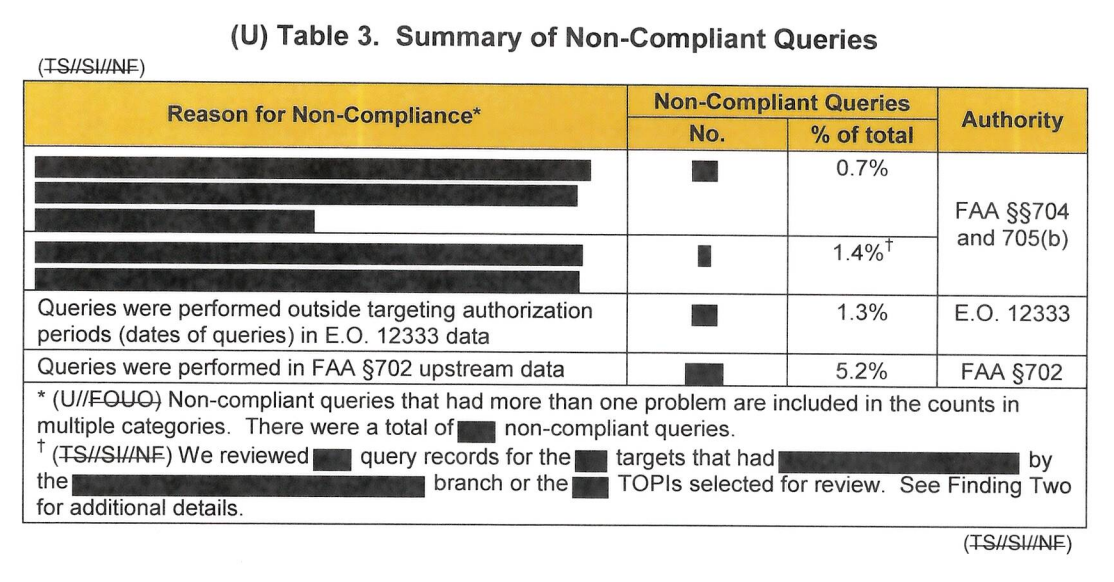

The review itself — conducted from March to August of 2015 on data from the first quarter of that year — showed a not insignificant amount of querying non-compliance.

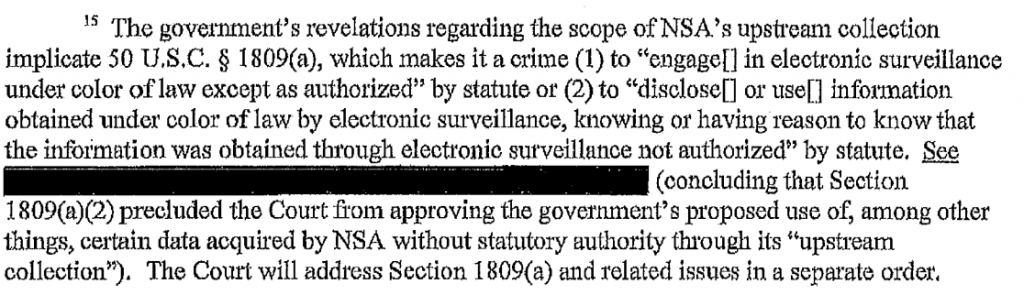

The 704 compliance problems are a part of the problem with NSA’s decision to shut down upstream surveillance (because 704 collection authorization is one of the things that automatically gets a US person approved for upstream searches]. Though, in her most biting comment in an otherwise pathetic opinion, Chief FISC judge Rosemary Collyer note the failure to tell her about this when 702 certificates were submitted in September or in an October 4 hearing showed a lack of candor.

At the October 26, 2016 hearing, the Court ascribed the government’s failure to disclose those IG and OCO reviews at the October 4, 2016 hearing to an institutional “lack of candor” on NSA’s part and emphasized that “this is a very serious Fourth Amendment issue.”

A review that post-dated the IG Report revealed the problem was even bigger than that. In the compliance section of the report, Collyer noted that 85% of the 704/705b queries conducting using one particular tool (which was rolled out in 2012) were non-compliant.

NSA examined all queries using identifiers for “U.S. persons targeted pursuant to Sections 704 and 705(b) of FISA using the tool [redacted] in [redacted] . . . from November 1, 2015 to May 1, 2016.” Id. at 2-3 (footnote omitted). Based on that examination, “NSA estimates that approximately eighty-five percent of those queries, representing [redacted] queries conducted by approximately [redacted] targeted offices, were not compliant with the applicable minimization procedures.” Id. at 3. Many of these non-compliant queries involved use of the same identifiers over different date ranges. Id. Even so, a non-compliance rate of 85% raises substantial questions about the propriety of using of [redacted] to query FISA data. While the government reports that it is unable to provide a reliable estimate of the number of non-compliant queries since 2012, id., there is no apparent reason to believe the November 2015-April 2016 period coincided with an unusually high error rate.

And NSA was unable to chase down the reporting based off this non-compliant querying.

The government reports that NSA “is unable to identify any reporting or other disseminations that may have been based on information returned by [these] non-compliant queries” because “NSA’s disseminations are sourced to specific objects,” not to the queries that may have presented those objects to the analyst. Id. at 6. Moreover, [redacted] query results are generally retained for just [redacted].

All of which is to say that the authority that the government has been pointing to for years to show how great Title VII is is really a dumpster fire of compliance problems.

And still, we know very little about how this authority is used.

The number of Americans affected is not huge — roughly 80 people approved under 704 plus anyone approved for domestic FISA order that goes overseas (though that would almost certainly include Carter Page). Still, if this is supposed to be the big protection Americans overseas receive, it hasn’t been providing much protection.