If Gun Buyers Were Mexican

The NYT has a follow-up on Charlie Savage’s earlier article about all the gun safety provisions lying dormant at DOJ. It describes the gaps in the background check system due to states not sharing their data with the federal government.

Nearly two decades after lawmakers began requiring background checks for gun buyers, significant gaps in the F.B.I.’s database of criminal and mental health records allow thousands of people to buy firearms every year who should be barred from doing so.

The database is incomplete because many states have not provided federal authorities with comprehensive records of people involuntarily committed or otherwise ruled mentally ill. Records are also spotty for several other categories of prohibited buyers, including those who have tested positive for illegal drugs or have a history of domestic violence.

In the past I’ve drawn a comparison between our country’s treatment of terrorists and gun nuts, arguing that it has prioritized the less urgent threat.

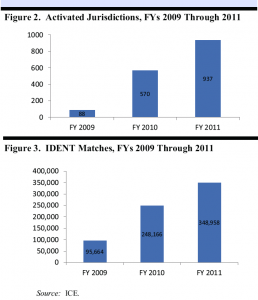

But this background check database raises interesting comparisons with DHS’ Secure Communities, particularly the effort to ensure that any undocumented person arrested for a crime gets deported. Like terrorism, Secure Communities has hit a point of diminishing returns. As with terrorism, Secure Communities is built to allow for false positives.

Nevertheless, the government has prioritized getting that database completely functioning, with participation from every state.

While the law also allowed the Justice Department to withhold some general law enforcement grant money from states that did not submit their records to the system, the department has not imposed any such penalties, the G.A.O. found.

Not so with gun buyers, apparently.

And the comparison here offers one other lesson. One reason for the delay in data-sharing from the states is the difficulty in implementing an appeals process.

After the Virginia Tech shooting, Congress enacted a law designed to improve the background check system, including directing federal agencies to share relevant data with the F.B.I. and setting up a special grant program to encourage states to share more information with the federal government. But only states that also set up a system for people to petition to get their gun purchasing rights restored were eligible under the law — a key concession to the National Rifle Association — which proved to be an extra hurdle many states have not yet overcome.

Frankly, ensuring people have due process is one of the least offensive things the NRA does (would that they championed the civil rights of felons more generally).

If we demand this for gun ownership, why don’t we demand it for far more damaging terrorism and deportation data mining?