On CIPA and Sequestration: Durham’s Discovery Deadends

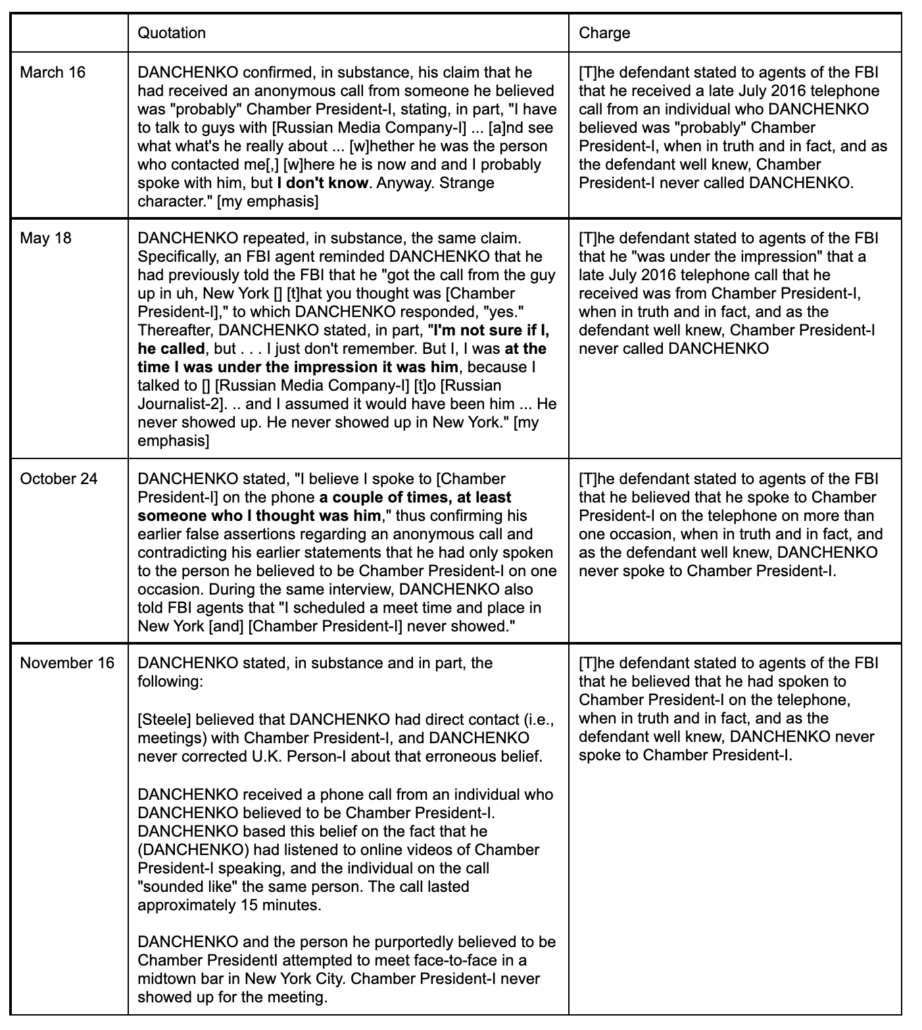

In this post, I laid out the range of highly classified or other potentially unavailable information that Igor Danchenko will be able to make a credible claim to need to defend himself against charges he knowingly lied to the FBI.

That list includes:

- Details about a Section 702 directive targeting Danchenko’s friend, Olga Galkina

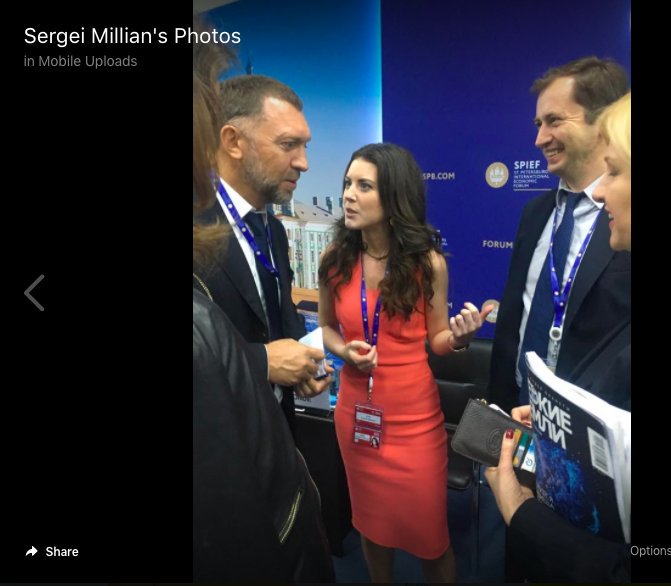

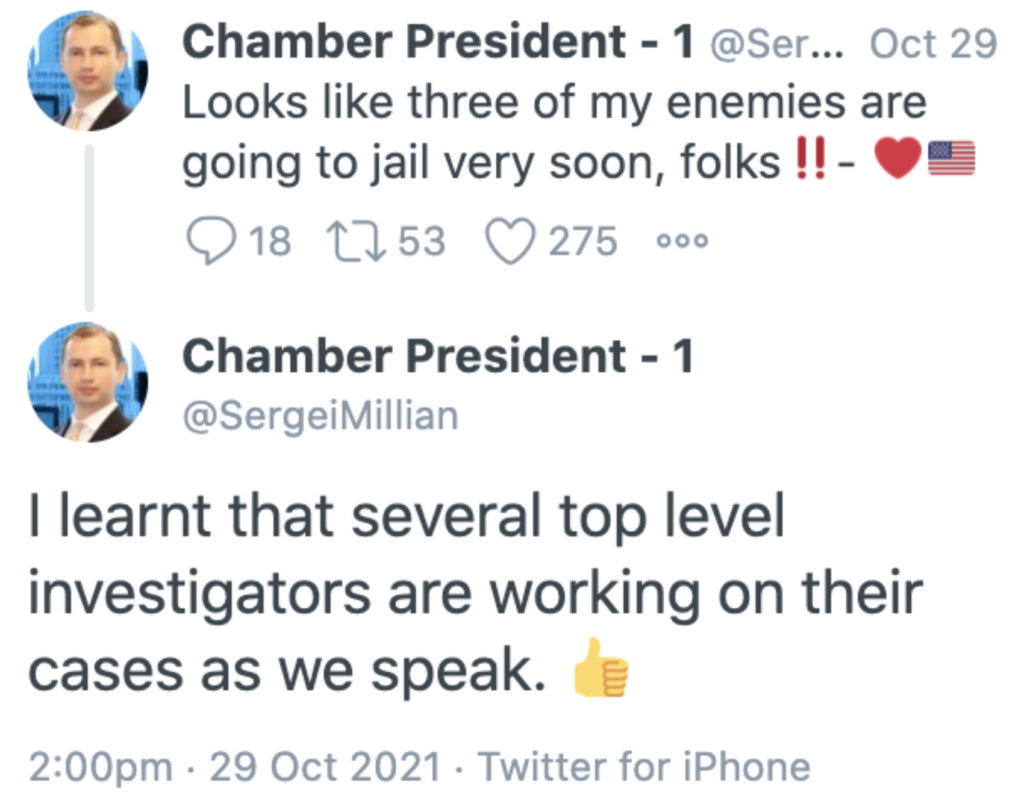

- Extensive details about Sergei Millian’s Twitter account, including proof that Millian was always the person running it

- Details of the counterintelligence investigation into Millian

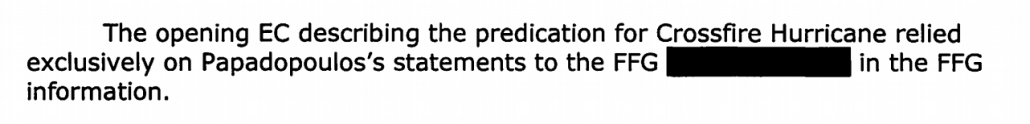

- Materials relating to Millian’s cultivation, in the same weeks as a contested phone call between Danchenko and Millian, of George Papadopoulos

- Evidence about whether Oleg Deripaska was Christopher Steele’s client for a project targeting Paul Manafort before the DNC one

- All known details of Deripaska’s role in injecting disinformation into the dossier, up through current day

- Details of all communications between Deripaska and Millian

- Details of the counterintelligence investigation into Carter Page

- Both the FISA applications targeting Page and the underlying discussions about them

- FISA-obtained collection that is helpful and material to Danchenko’s defense, including all substantive collection incriminating Page obtained before Danchenko’s January interviews, and all intelligence relating to the specific alleged lies in the indictment

- Materials relating to FBI’s attempt to corroborate the dossier, including materials from Page’s FISA collection that either corroborated or undermined it

As I noted, I know of no prior case where a defendant has had notice of two separate FISA orders as well as a sensitive ongoing counterintelligence investigation and a credible claim to need that information to mount a defense. Durham has committed to potentially impossible discovery obligations, all to prosecute five (or maybe two) lies that aren’t even alleged to have willingly obstructed an investigation. For reasons I lay out below, Durham may not, legally, be able to do that.

To be quite clear: that Danchenko can make a credible claim to need this stuff doesn’t mean he’ll get it, much less be permitted to present it at trial. But, particularly given that the two FISA orders and the counterintelligence investigations have all been acknowledged, DOJ can’t simply pretend they don’t have the evidence. For perhaps the first time ever, DOJ doesn’t get to decide whether to rely on FISA information at trial, because the indictment was written to give the defense good cause to demand it.

Still, much of this stuff will be dealt with via the Classified Information Proecdures Act, CIPA. CIPA is a process that purports to give the government a way to try prosecutions involving classified information, balancing discovery obligations to a defendant with the government’s need to protect classified information. (Here’s another description of how it works.)

Effectively, Danchenko will come up with a list similar to the one above of classified information he believes exists that he needs to have to mount a defense. The government will likewise identify classified information that it believes Danchenko is entitled to under discovery rules. And then the judge — Anthony Trenga, in this case — decides what is material and helpful to Danchenko’s defense. Then the government has the ability to “substitute” language for anything too classified to publicly release, some of it before ever sharing with the defendant, the rest after a hearing including the defense attorneys about what an adequate substitution is.

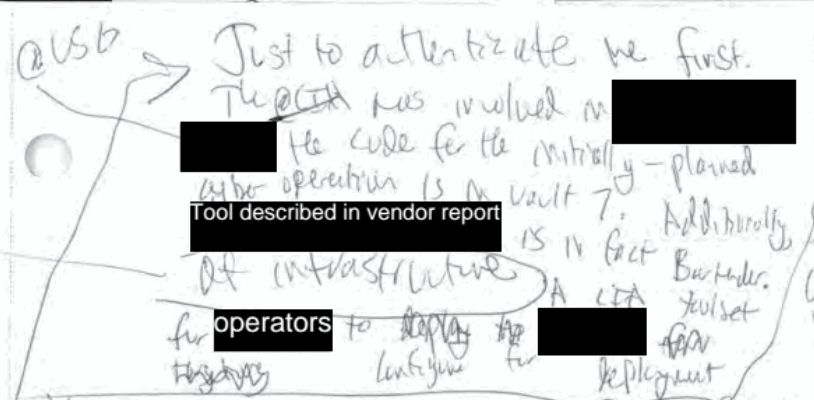

Here’s a fragment of an exhibit from the Joshua Schulte case that shows the end product of the CIPA process: The CIA was able to replace the name of a vendor the CIA used (presumably as a cover) with the generic word, “vendor,” thereby preventing others from definitively attributing the cover with the CIA. It replaced the description of those who would use the hacking tool with “operators.” Elsewhere, the same exhibit replaced the name of one of Schulte’s colleagues. It redacted several other words entirely.

Here are some more exhibits — CIA Reports submitted at the Jeffrey Sterling trial — that show the outcome of the CIPA process.

On top of the fact that CIPA adds a way for the government to impose new roadblocks on discovery (and discovery only begins after a defendants’ attorneys are cleared), it can end up postponing the time when the defendant actually gets the evidence he will use at trial. So it generally sucks for defendants.

But the process is also onerous for the prosecutor. Basically, the prosecutor has to work with classification authorities from the agency or agencies that own particular classified information and cajole them to release enough information to get past the CIPA review. In my earlier post, I described that Patrick Fitzgerald had to do this with the Presidential Daily Briefs, and it took him several attempts before he had declassified enough information to satisfy Judge Reggie Walton that it provided Scooter Libby with the means to make his defense. If the agency involved in the CIPA process hasn’t totally bought off on the importance of the prosecution, they’re going to make the process harder. Often, the incentive for agencies to cooperate stems from the fact that the defendant is accused of leaking secrets that the agency in question wants to avenge.

Because the process is so onerous, DOJ works especially hard to get defendants to plead before the CIPA process, and often because the defendant is facing the kind of stiff sentence that comes with Espionage charges, CIPA makes it more likely they’ll plead short of trial.

Those two details already make Danchenko’s trial different from most CIPA cases. That’s true, first of all, because Danchenko never had any agency secrets, and prosecutors will be forced to persuade multiple agencies (at least the FBI and NSA, and possibly CIA and Treasury) to give a Russian national secrets even though his prosecution will set no example against leaking for the agencies. Indeed, the example Danchenko will be setting, instead, is that the FBI doesn’t honor its commitments to keep informant identities safe. Additionally, there’s little reason for Danchenko to plead guilty, as the punishment on five 18 USC 1001 charges would not be much different than one charge (remember, Kevin Clinesmith got probation for his 18 USC 1001 conviction), and Danchenko would still face deportation after he served any sentence, where he’s likely to face far greater retaliation than anything US prisons would pose. That will influence the CIPA process, too, as a successful prosecution would likely result in the Russian government coercing access to whatever secrets that intelligence agencies disclose to Danchenko during the prosecution.

CIPA always skews incentives, but this case skews incentives differently than other CIPA cases.

Add in that Judge Trenga, the judge in this case, has been pondering CIPA issues of late in the case of Bijan Kian, Mike Flynn’s former partner, who was prosecuted on Foreign Agent charges. Trenga was long unhappy with the way DOJ charged Kian’s case, and grew increasingly perturbed with DOJ’s attempts to salvage the case after Flynn reneged on his cooperation agreement. Trenga overturned the jury’s guilty verdict, but was subsequently reversed on that decision by the Fourth Circuit. Since then, Kian has been demanding two things: more access to classified materials underlying evidence he was given pursuant to the CIPA process right before trial showing previously undisclosed contacts between Flynn and Ekim Alptekin not involving Kian, and a new trial, partly based on late and inadequate disclosure of that CIPA information.

Following a series of ex parte hearings regarding classified evidence pursuant to the Confidential Information Procedures Act (“CIPA”), the government, on the eve of trial, handed Rafiekian a one-sentence summary, later introduced as Defendant’s Exhibit 66 (“DX66”), informing Rafiekian that the government was aware of classified evidence relating to interactions between Flynn and Alptekin that did not “refer[] to” Rafiekian. DX66.1 Following receipt of DX66, Rafiekian immediately sought access to the underlying information pursuant to CIPA because “[i]t goes right to the question of what happened and what he knew and what statements were made and who was making them,” and “[i]f Mr. Rafiekian is convicted without his counsel having access to this exculpatory evidence, we believe it will go right to the heart of his due process and confrontation rights.” Hr’g Tr. 31 (Jul. 12, 2019), ECF No. 309. The Court took the request under advisement, noting that it “underst[ood] the defense’s concern and w[ould] continue to consider whether additional disclosure of information” would be necessary as the case developed. Id. at 32. At trial, the government used DX66 in its rebuttal argument in closing to show that Rafiekian participated in the alleged conspiracy—“even though the information in that exhibit related solely to Flynn and explicitly excluded Rafiekian.” Rafiekian, 2019 WL 4647254, at *17.

1 DX66 provides in full: The United States is in possession of multiple, independent pieces of information relating to the Turkish government’s efforts to influence United States policy on Turkey and Fethullah Gulen, including information relating to communications, interactions, and a relationship between Ekim Alptekin and Michael Flynn, and Ekim Alptekin’s engagement of Michael Flynn because of Michael Flynn’s relationship with an ongoing presidential campaign, without any reference to the defendant or FIG.

With regards to the first request, Trenga has ruled that Kian can’t have the underlying classified information, because (under CIPA’s guidelines) the judge determined that, “the summary set forth in DX Exhibit 66 provides the Defendant with substantially the same ability to make his defense as would disclosure of the specific classified information.” But his decision on the second issue is still pending and Trenga seems quite open to Kian’s request for a new trial. So Danchenko and Durham begin this CIPA process years into Trenga’s consideration about how CIPA affects due process in the Kian case. I don’t otherwise expect Trenga to be all that sympathetic to Danchenko, but if Trenga grants Kian a new trial because of the way prosecutors gained an unfair advantage with the CIPA process (by delaying disclosure of a key fact), it will be a precedent for and hang over the CIPA process in the Danchenko case.

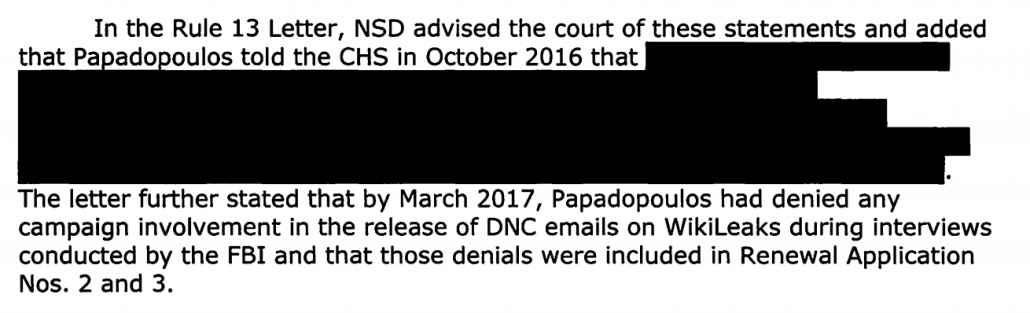

Then there are unique challenges Durham will face even finding everything he has to provide Danchenko under Brady. In the Michael Sussmann case, I’ve seen reason to believe Durham doesn’t understand the full scope of where he needs to look to find evidence relevant to that case. But given the centrality of investigative decisions in the Danchenko case — and so the Mueller investigation — to Durham’s materiality claims, Durham will need to make sure he finds everything pertaining to Millian, Papadopoulos, and Kiliminik and Deripaska arising out of the Mueller case. In the case of Steve Calk, that turned out to be more difficult than prosecutors initially imagined.

But all of these things — the multiple sensitive investigations relevant to Danchenko’s defense, normal CIPA difficulties, unique CIPA difficulties, and the challenges of understanding the full scope of the Mueller investigation — exist on top of another potential problem: DOJ doesn’t control access to some of the most important evidence in this case.

As I noted in my earlier post, there are multiple things FBI obtained by targeting Carter Page that Danchenko will be able to demand to defend himself against Durham’s materiality claims. For example, FBI obtained information under FISA that seems to undercut Page’s claims that he didn’t meet with Igor Diveykin, a claim Danchenko sourced to Olga Galkina, who is central to Durham’s materiality claims.

If this information really does show that Page was lying about his activities in Russia, it would provide proof that after the initial FISA order, FBI had independent reason to target Page.

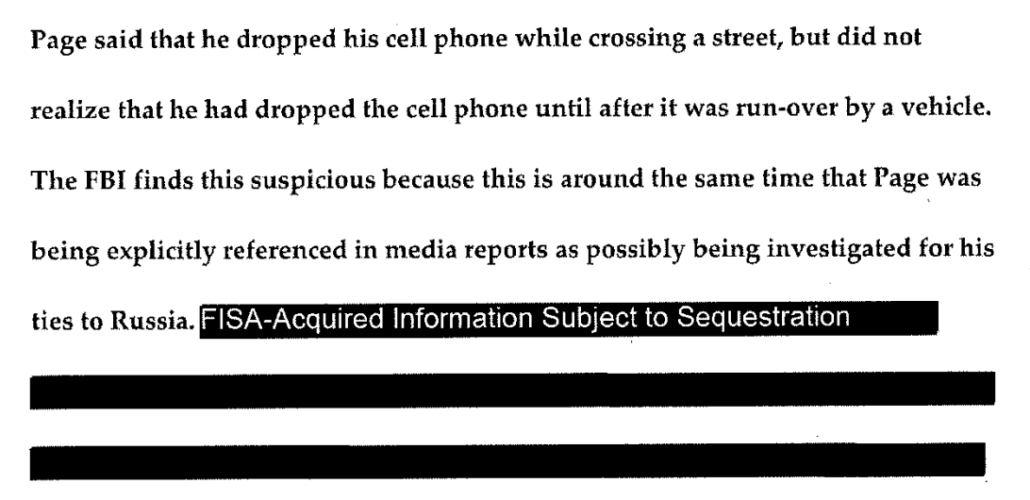

Similarly, FBI believed that Page’s explanation for how he destroyed the phone he was using in Fall 2016 was an excuse made up after he knew he was being investigated; that belief seems to be based, in part, on information obtained under FISA.

The FBI’s suspicions about that broken phone seem to be related to their interest in collecting on an encrypted messaging app Page used, one of the two reasons why FBI sought reauthorization to target Page in June 2017. Danchenko will need this information to prove that the June 2017 reauthorization was driven entirely by a desire to get certain financial and encrypted communication evidence, and so could not have been affected by Danchenko’s May and June 2017 interviews.

Information obtained from targeting Page under FISA will similarly be central to Danchenko’s defense against Durham’s claims that his alleged lies prevented FBI from vetting the dossier. That’s because the spreadsheet that FBI used to vet the dossier repeatedly relied on FISA-collected information to confirm or rebut the dossier. Some of that pertains to whether Page met with Igor Diveykin, an allegation Danchenko sourced to Olga Galkina, making it central to his defense in this case.

Other FISA-collected material was used to vet the Sergei Millian claim, which Durham charged in four of five counts.

Some of this may not be exculpatory (though some of it clearly would be). But it is still central to the case against Danchenko.

The thing is, Durham may not be legally able to use this information in Danchenko’s prosecution, and even if he is, it will further complicate the CIPA process.

Back on January 7, 2020, James Boasberg — acting in his role as the then-presiding FISA Judge — ordered that the FBI adopt limits on the use of any information obtained via the four Carter Page FISA orders. Such orders are one of the only tools that the FISA Court has to prohibit the use of information that the Executive collects but later determines did not comply with FISA (the government only retracted the probable cause claims for the third and fourth FISA orders targeting Page, but agreed to sequester all of it). A subsequent government filing belatedly obtaining permission to use material obtained via those FISA orders in conjunction with Carter Page’s lawsuit laid out the terms of that sequester. It revealed that, according to a June 25, 2020 FISA order, the government can only legally use material obtained under those FISA orders for the following purposes:

- Certain identified ongoing third-party litigation pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- Ongoing and anticipated FOIA and civil litigation with Page

- FBI review of the conduct of its personnel involved in the Page investigation

- DOJ OIG monitoring of the implementation of one of the recommendations stemming from the OIG Report

- The review of the conduct of Government personnel in the Page and broader Crossfire Hurricane investigations [my emphasis]

On November 23, 2020, Boasberg issued a follow-up order in response to learning, on October 21, 2020, that DOJ had already shared sequestered FISA information with the US Attorney for Eastern Missouri (the Jeffrey Jensen review), the US Attorney for DC (possibly, though not certainly, the Durham case), and the Senate Judiciary Committee (FISC may have learned of the latter release when the vetting spreadsheet was publicly released days before DOJ informed FISC of that fact). Effectively, Bill Barr’s DOJ had confessed to the FISA Court that it had violated FISA by disseminating FISA-collected information later deemed to lack probable cause without first getting FISC approval. Boasberg ordered DOJ to “dispossess” the MOE USAO and DC USAO of the sequestered information and further ordered that those US Attorneys, “shall not access materials returned to the FBI … without the prior approval of the Court.”

There’s no evidence that Durham obtained approval to access this information (though DOJ applications to FISC often don’t get declassified, so it’s not clear it would show up in the docket). And when I asked DOJ whether Durham had obtained prior approval to access this sequestered information even for his own review, much less for use in a prosecution, I got no response. While accessing the sequestered material for review of the conduct of Government personnel is among those permitted by the original order (bolded above), using it to review the conduct of non-governmental sources like Danchenko was not, to say nothing of prosecuting such non-governmental sources. To get approval to use sequestered information in the Danchenko case, Durham would have to convince FISC to let Durham share such information with a foreign national whose prosecution would lead to his deportation to Russia. And if he shared the information without FISC approval, then Durham himself would be violating FISA.

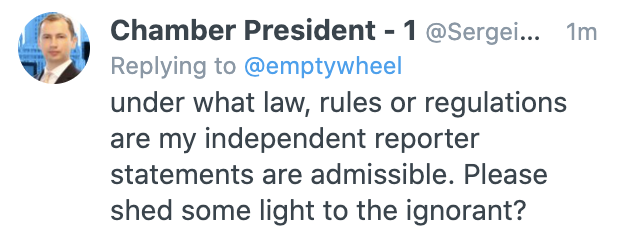

To be sure, it would be the most unbelievable kind of malpractice to charge the Danchenko case without, first, ascertaining how Durham was going to get this sequestered information. I’d be shocked if Durham hadn’t gotten approval first. But then, I was shocked that when Durham charged Kevin Clinesmith, he didn’t know what crimes FBI investigated Page for. I am shocked that Durham used Sergei Millian’s Twitter feed to substantiate a factual claim that Millian didn’t speak with Danchenko. So who knows? Maybe Durham has not yet read this evidence, to say nothing of ensuring he can share it with a Russian national in discovery. It would shock me, but I’m growing used to being shocked by Durham’s recklessness.

In any case, depending on what the FISC has decided about disseminating — and making public — this sequestered information, it will, at the very least, create additional challenges for Durham. Durham couldn’t just assert that DOJ IG had determined that the this information was not incriminating to Page and therefore not helpful to Danchenko to avoid sharing the sequestered FISA information. Under CIPA, Judge Trenga would need to review the information himself and assess whether information obtained under Page’s FISA was material and helpful to Danchenko’s defense. If he decided that Danchenko was entitled to it in his defense, then Durham might have to fight not just with FBI and NSA to determine an adequate substitution for that information, but also FISC itself.

CIPA assumes that the Executive owns the classification decisions regarding any information to be presented at trial, and therefore the Executive gets to balance the value of the prosecution against the damage declassifying the information would do. Here, as with Fitzgerald, a Special Counsel will be making those decisions, setting up a potential conflict with all the agencies that may object. But here, FISC has far more interest in the FISA information than it would if (say) it were just approving the use of FISA-obtained material to prosecute the person targeted by that FISA.

Again, John Durham is going to have to declassify a whole bunch of sensitive information, including information sequestered to protect Carter Page, to give it to a foreign national who never had those secrets such that, if Durham succeeds at trial, it may lead inevitably to Russia obtaining that sensitive information. All that for five shoddily-charged false statements charges. This is the kind of challenge that a prosecutor exercising discretion would not take on.

But Durham doesn’t seem to care that he’s going to damage all the people he imagines are victims as well as national security by bringing this case to trial.

Danchenko posts

The Igor Danchenko Indictment: Structure

John Durham May Have Made Igor Danchenko “Aggrieved” Under FISA

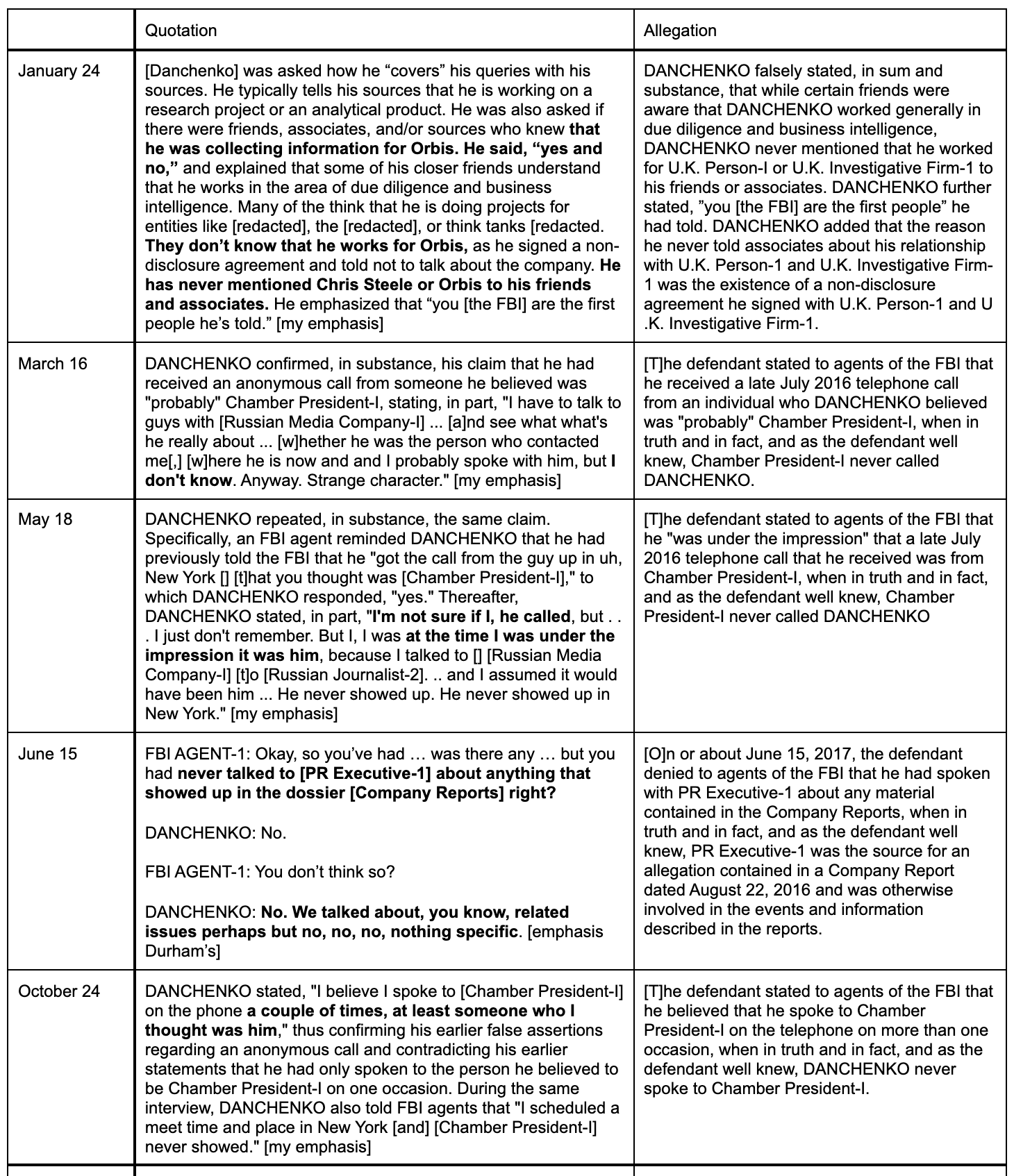

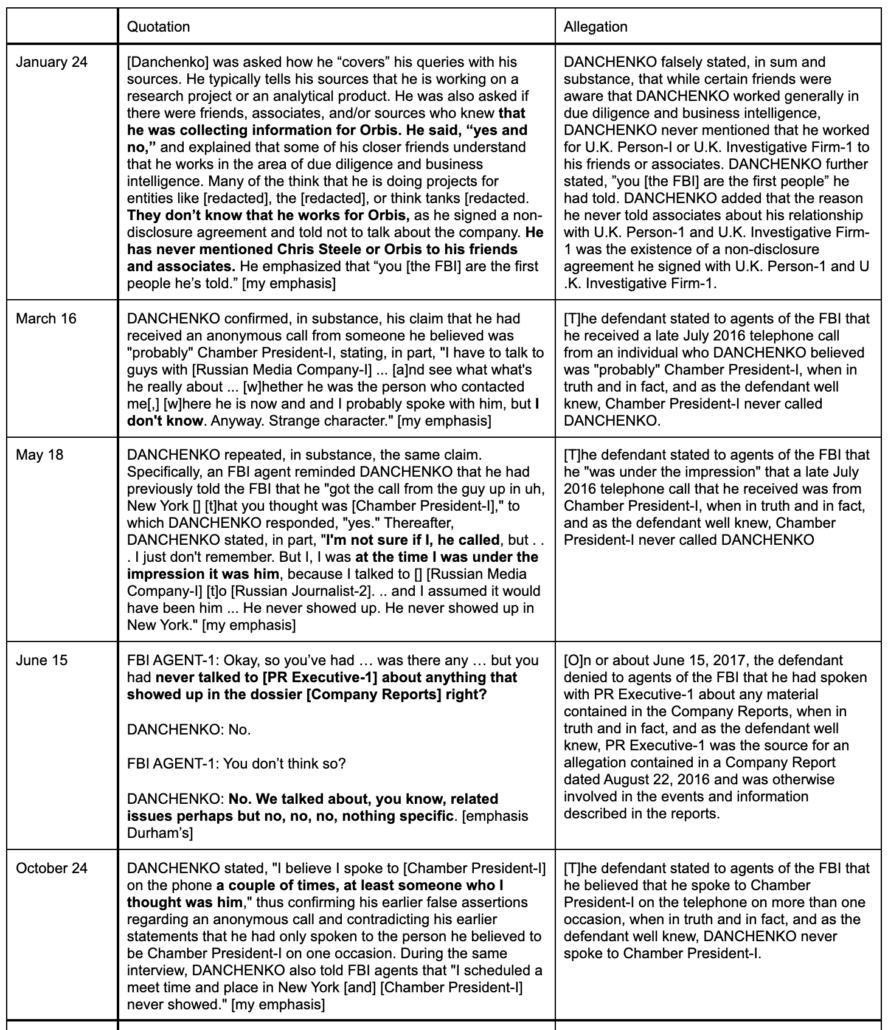

“Yes and No:” John Durham Confuses Networking with Intelligence Collection

Source 6A: John Durham’s Twitter Charges

John Durham: Destroying the Purported Victims to Save Them

John Durham’s Cut-and-Paste Failures — and Other Indices of Unreliability