Trump Finally Describes How FBI Injured Him: By Taking his Celine Dion Picture

The most important part of the hearing in the stolen document case before the 11th Circuit Tuesday came when Chief Judge William Pryor asked what the 11th Circuit should do if they find for DOJ.

It seemed to me that because this is an appeal from an injunction for purposes of appellate jurisdiction, what we would do if you’re right we would vacate the injunction, vacate this order on the ground that there is a lack of equitable jurisdiction. But that would be it. What we would have jurisdiction over is not the entire case. We would have jurisdiction, if we have jurisdiction, it’s over that order, granting an injunction. Isn’t that right, technically, instead of reverse and remand, with instructions, it’s really just vacate.

If Pryor’s original view was right, it would allow DOJ to use the documents in a prosecution of Trump, but would leave Judge Aileen Cannon with the authority to still meddle in the case.

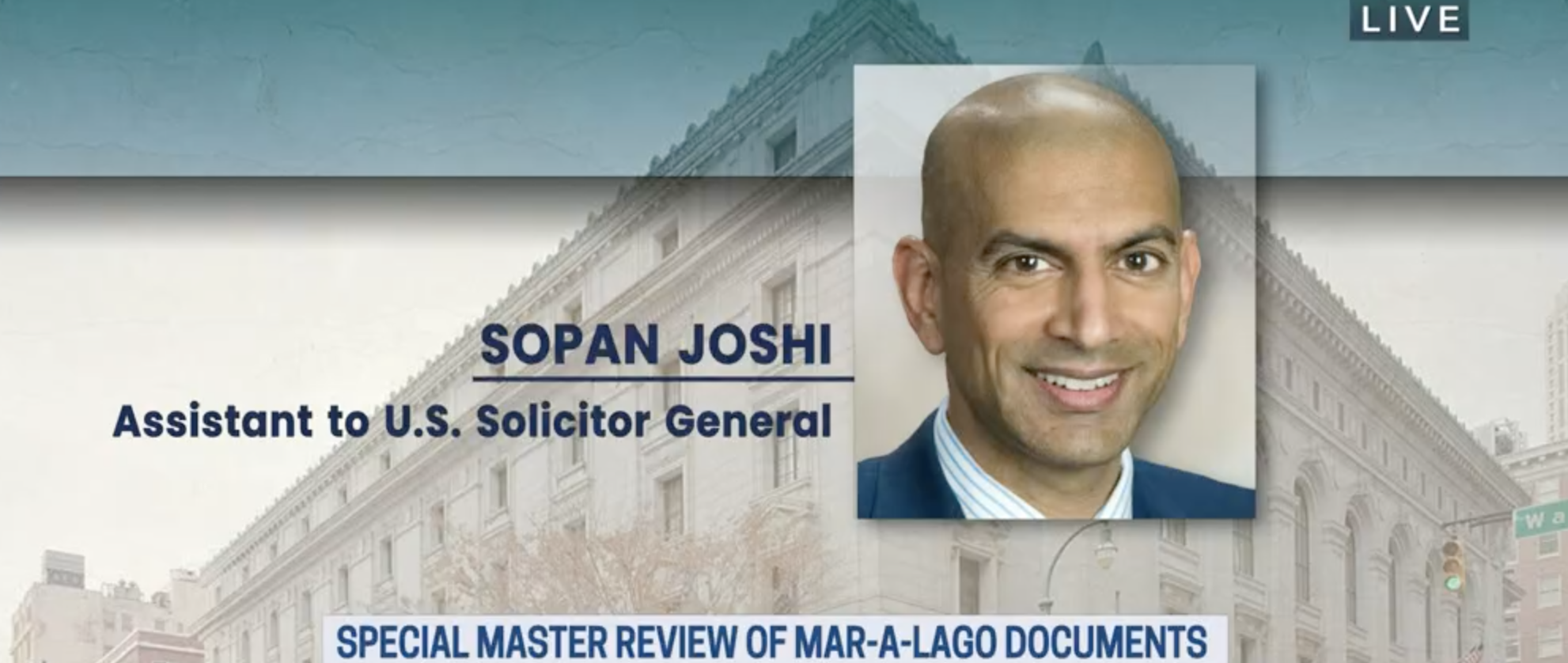

Sopan Joshi, arguing for DOJ, disagreed and walked Judge Pryor through a SCOTUS precedent that says that the Court would necessarily have the authority to reverse the decision entirely.

Joshi must have persuaded, to some degree, because Pryor decided,

If you’re right, what we’re really talking about is a middle position, that is, I was right about vacate but you’re right about the authority to remand with instructions to dismiss. Ordinarily if a District Court lacks jurisdiction, that’s what we do. We vacate and remand with instructions to dismiss.

Joshi replied, “Fair enough, and I’m not going to fight you too hard on it.

Judge Britt Grant then piped in to ask Joshi whether,

We, in your view, if we decide there was not equitable jurisdiction in the first place we wouldn’t need to go through the bases of jurisdiction for the injunction and Special Master or anything like that. The lack of jurisdiction as it was brought would resolve all the questions in your mind. Is that right?

Joshi was pretty happy with that too. “I think that’s right.”

This technical debate, which took up about a quarter of the hearing, not only betrays that at least two of the 11th Circuit Court judges are thinking of how to give DOJ what it wants, but how to do so procedurally. And they seemed persuaded, ultimately, that they should just vacate the entire Special Master appointment altogether, ending the entire Special Master process.

Things didn’t go so well for Jim Trusty, Trump’s lawyer. Just as he started to get going on claims about Biden ordering a search on a political candidate’s home (a lie), Grant interrupted and corrected his use of raid: “Do you think ‘raid’ is the right word for execution of a warrant?”

When Trusty tried to claim that this warrant had been a general warrant, Pryor scolded, “but you didn’t establish that it was a general warrant,” the first of multiple times when the judges reminded Trusty he had not made the arguments he presented today before, not before any court. Grant pointed out that Trusty was misstating what their purported goal was, which was originally to review for privilege.

Then, as Trusty reeled off the things FBI seized that, he said, were incredibly personal, Grant asked, “Do you think it’s rare for the target of a warrant to think it’s overreaching?”

Mic drop!

She was back again, a few minutes later, as Trusty tried to argue what he thought the binding precedent should be, rather than what it was. Grant got to the core issue, which was that Trusty was asking for special treatment.

If you set aside, which I understand that you won’t want to do, but if you do for the purposes of this question, set aside the fact that the target of the search warrant was a former president, are there any arguments that would be different than any defendant, any target of a warrant who wished to challenge a warrant before an indictment.

Trusty tried to reframe her question. “We’re not looking for special treatment for President Trump. We are recognizing there is a context here where no President–”

Pryor interrupted.

I don’t know that that’s particularly responsive. The question was, set aside the fact that the subject of the warrant is the President. What’s to distinguish this from any other subject of a criminal investigation?

When Trusty tried to raise the concerns that he claimed Trump had had all along, Pryor responded, “I don’t see where that case has been made.” Again, Trump didn’t make the arguments he needed to, in September, to get the relief he is demanding now.

That’s when Pryor laid out the real practical problem with Trusty’s claims.

We have to determine when it’s proper for a District Court to do this in the first place, which is what we’re looking at now. And the last question was one posed that makes clear that basically, other than the fact that this involves a former President, everything else about this is indistinguishable from any pre-indictment search warrant. And we’ve got to be concerned about the precedent that we would create that would allow any target of a federal criminal investigation to go into a district court and to have a district court entertain this kind of petition, exercise equitable jurisdiction, and interfere with the Executive Branch’s ongoing investigation.

After Trusty started wailing more about personal documents, Pryor described,

You’ve talked about all these other records and property that were seized. The problem is the search warrant was for classified documents and boxes and other items that are intermingled with that. I don’t think it’s necessarily the fault of the government if someone has intermingled classified documents and all kinds of other personal property.

That’s when Trusty revealed that FBI took a picture of Celine Dion.

Dion, remember, refused Trump’s request to play his inauguration.

Now Trump’s grave injury all begins to make sense! FBI hurt him by taking his Celine Dion picture. All the wailing and screaming since August now begin to make sense.

Trusty went on blathering, claiming — for example — that the injunction hadn’t harmed the government because they had months before and after the seizure to conduct their investigation. When Trusty claimed the injunction was overblown, Pryor invited,

Think of the extraordinary nature from our perspective of an injunction against the Executive Branch in a pre-indictment situation. Under the separation of powers, the judiciary doesn’t interfere with those kinds of prosecutorial and investigatory decisions. Right? That’s the whole nature of this kind of jurisdiction.

After Pryor asked about a new argument Trusty was making, Joshi reeled off the five different arguments that Trump has advanced.

Joshi closed with the practical fear Pryor had raised: If Trump has his way, every “defendant” will demand pre-indictment intervention.

This emphasizes how anomalous and extraordinary what the district court did her was. And I heard Mr. Trusty agree that there was no difference between this and other defendants. And I think that just emphasizes how the anomalous could become commonplace. And we think the court should reverse.

Andrew Brasher seemed more sympathetic to Trusty’s arguments, at one point asking how much more of a delay this would cause, as if he might let this all play out (and that’s what would happen if the 11th didn’t entirely vacate Cannon’s order.

But ultimately, Trump was treated as if not a defendant, then at least someone who could create untenable rights for other defendants, which sounded like something neither Pryor nor Grant were willing to do.